K a H O ' O L a W E : a L O H No State of H a W a Ii

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DI CP19 F1 Ocrcombined.Pdf

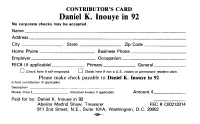

CONTRIBUTOR’S CARD Daniel K. Inouye in 92 No corporate checks may be accepted. Name ______________________________________________________________________ Address ____________________________________________________________________ C ity _________________ S ta te ___________________ Zip C ode __________________ Home Phone ________________________ Business Phone ________________________ Employer ____________________________ Occupation ___________________________ FEC# (if applicable) _____________ Primary ______________ General ______________ d l Check here if self-employed. CH Check here if not a U.S. citizen or permanent resident alien. Please make check payable to Daniel K. Inouye in 92 In-kind contribution (if applicable) Description ___________________________________________________ Market Price $ _____________________ (Attached invoice if applicable) Amount _$ ___________________ Paid for by: Daniel K. Inouye in 92 ______________ Abelina Madrid Shaw, Treasurer FEC # C00213314 911 2nd Street, N.E., Suite 101 A, Washington, D.C. 20002 This information is required of all contributions by the Federal Election Campaign Act. Corporation checks or funds, funds from government contractors and foreign nationals, and contributions made in the name of another cannot be accepted. Contributions or gifts to Daniel K. Inouye in 92 are not tax deductible. A copy of our report is on file with the Federal Election Commission and is available for purchase from the Federal Election Commission, Washington, D.C. 20463. JUN 18 '92 12=26 SEN. INOUYE CAMPAIGN 808 5911005 P.l 909 KAPIOLANI BOULEVARD HONOLULU, HAWAII 96814 (808) 591-VOTE (8683) 591-1005 (Fax) FACSIMILE TRANSMISSION TO; JENNIFER GOTO FAX#: NESTOR GARCIA FROM: KIMI UTO DATE; JUNE 1 8 , 1992 SUBJECT: CAMPAIGN WORKSHOP Number of pages Including this cover sheet: s Please contact K im i . at (808) 591-8683 if you have any problems with this transmission. -

F—18 Navy Air Combat Fighter

74 /2 >Af ^y - Senate H e a r tn ^ f^ n 12]$ Before the Committee on Appro priations (,() \ ER WIIA Storage ime nts F EB 1 2 « T H e -,M<rUN‘U«sni KAN S A S S F—18 Na vy Air Com bat Fighter Fiscal Year 1976 th CONGRESS, FIRS T SES SION H .R . 986 1 SPECIAL HEARING F - 1 8 NA VY AIR CO MBA T FIG H TER HEARING BEFORE A SUBC OMMITTEE OF THE COMMITTEE ON APPROPRIATIONS UNITED STATES SENATE NIN ETY-FOURTH CONGRESS FIR ST SE SS IO N ON H .R . 9 8 6 1 AN ACT MAKIN G APP ROPR IA TIO NS FO R THE DEP ARTM EN T OF D EFEN SE FO R T H E FI SC AL YEA R EN DI NG JU N E 30, 1976, AND TH E PE RIO D BE GIN NIN G JU LY 1, 1976, AN D EN DI NG SEPT EM BER 30, 1976, AND FO R OTH ER PU RP OSE S P ri nte d fo r th e use of th e Com mittee on App ro pr ia tio ns SPECIAL HEARING U.S. GOVERNM ENT PRINT ING OFF ICE 60-913 O WASHINGTON : 1976 SUBCOMMITTEE OF THE COMMITTEE ON APPROPRIATIONS JOHN L. MCCLELLAN, Ark ans as, Chairman JOH N C. ST ENN IS, Mississippi MILTON R. YOUNG, No rth D ako ta JOH N O. P ASTORE, Rhode Island ROMAN L. HRUSKA, N ebraska WARREN G. MAGNUSON, Washin gton CLIFFORD I’. CASE, New Je rse y MIK E MANSFIEL D, Montana HIRAM L. -

America Practices Its Imperial Power

Name: Date: Period: . Directions: Read the history of Hawaii’s annexation and the Queen’s letter to President McKinley before answering the critical thinking questions. America practices its Imperial Power Hawaii was first occupied by both the British and the French before signing a friendship treaty with the United States in 1849 that would protect the islands from European Imperialism. Throughout the 1800s many missionaries and businessmen travel to Hawaii. Protestant missionaries wished to convert the religion of locals and the businessmen are interested in establishing money making sugar plantations. Hawaii was a useful resource to the United States not only because of its rich land, but because of its location as well. The islands are located in a spot that U.S. leaders thought was ideal for a naval port. This base, Pearl Harbor, would give America presence in the Pacific Ocean and create a refueling port for ships in the middle of the ocean. When Queen Liliuokalani took the thrown in 1891 she wanted to limit the power that American business have in Hawaii. America also changed the trading laws, making it extremely expensive for the Hawaiian plantations to export their sugar product back to the mainland. In 1893 these plantation owners, led by Samuel Dole and with the support of the United States Marines revolt against the Queen and forced her into surrendering the thrown. With American businessmen in control, they set up their own government appointing Samuel Dole as governor. With plantation owners in control, it was in their best interest for their business trade to become a part of the United States and they requested to be annexed. -

1856 1877 1881 1888 1894 1900 1918 1932 Box 1-1 JOHANN FRIEDRICH HACKFELD

M-307 JOHANNFRIEDRICH HACKFELD (1856- 1932) 1856 Bornin Germany; educated there and served in German Anny. 1877 Came to Hawaii, worked in uncle's business, H. Hackfeld & Company. 1881 Became partnerin company, alongwith Paul Isenberg andH. F. Glade. 1888 Visited in Germany; marriedJulia Berkenbusch; returnedto Hawaii. 1894 H.F. Glade leftcompany; J. F. Hackfeld and Paul Isenberg became sole ownersofH. Hackfeld& Company. 1900 Moved to Germany tolive due to Mrs. Hackfeld's health. Thereafter divided his time betweenGermany and Hawaii. After 1914, he visited Honolulu only threeor fourtimes. 1918 Assets and properties ofH. Hackfeld & Company seized by U.S. Governmentunder Alien PropertyAct. Varioussuits brought againstU. S. Governmentfor restitution. 1932 August 27, J. F. Hackfeld died, Bremen, Germany. Box 1-1 United States AttorneyGeneral Opinion No. 67, February 17, 1941. Executors ofJ. F. Hackfeld'sestate brought suit against the U. S. Governmentfor larger payment than was originallyallowed in restitution forHawaiian sugar properties expropriated in 1918 by Alien Property Act authority. This document is the opinion of Circuit Judge Swan in The U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals forthe Second Circuit, February 17, 1941. M-244 HAEHAW All (BARK) Box 1-1 Shipping articleson a whaling cruise, 1864 - 1865 Hawaiian shipping articles forBark Hae Hawaii, JohnHeppingstone, master, on a whaling cruise, December 19, 1864, until :the fall of 1865". M-305 HAIKUFRUIT AND PACKlNGCOMP ANY 1903 Haiku Fruitand Packing Company incorporated. 1904 Canneryand can making plant installed; initial pack was 1,400 cases. 1911 Bought out Pukalani Dairy and Pineapple Co (founded1907 at Pauwela) 1912 Hawaiian Pineapple Company bought controlof Haiku F & P Company 1918 Controlof Haiku F & P Company bought fromHawaiian Pineapple Company by hui of Maui men, headed by H. -

Center for Hawaiian Sovereignty Studies 46-255 Kahuhipa St. Suite 1205 Kane'ohe, HI 96744 (808) 247-7942 Kenneth R

Center for Hawaiian Sovereignty Studies 46-255 Kahuhipa St. Suite 1205 Kane'ohe, HI 96744 (808) 247-7942 Kenneth R. Conklin, Ph.D. Executive Director e-mail [email protected] Unity, Equality, Aloha for all To: HOUSE COMMITTEE ON JUDICIARY For hearing Tuesday, March 19, 2019 Re: SB 1451, SD1, HD1 RELATING TO STATE HOLIDAYS. Recognizes La Ku‘oko‘a, Hawaiian Recognition Day, as an official state holiday. (SB1451 HD1) TESTIMONY IN OPPOSITION It is both funny and sad to see that so many legislators have signed their names in support of this bill, which is deceptively named and would be bad policy. Pandering to anti-American secessionists is a very bad idea. This bill is not about memorializing a success of diplomacy from 1843, it's about supporting a highly divisive cult of activists who want to enlist you as a partisan in an ideological civil war which threatens to rip the 50th star off our flag. SB1451,SD1,HD1 La Ku'oko'a Page !1 of !7 HSE JUD 3/19/19 Maybe you'll step away from this bill when you see how your predecessors in the 2007 legislature were lied to and fooled by the same gang now pushing this bill, and then those legislators were justly ridiculed for their pandering. The following points are proved in detail later in this testimony. Please take the time to read the details. 1. The word "ku'oko'a" does NOT mean "recognition" -- it means "independence". Look it up in the dictionary. Also apply, to two other bills, this lesson on how easy it is to fool you legislators about the meaning of Hawaiian words -- I refer to SB195 and SB642, which would make it law that if a bill "was originally drafted in Hawaiian and the English version was translated based on the Hawaiian version, the Hawaiian version shall be held binding." 2. -

![CHAIRMEN of SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–Present](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8733/chairmen-of-senate-standing-committees-table-5-3-1789-present-978733.webp)

CHAIRMEN of SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–Present

CHAIRMEN OF SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–present INTRODUCTION The following is a list of chairmen of all standing Senate committees, as well as the chairmen of select and joint committees that were precursors to Senate committees. (Other special and select committees of the twentieth century appear in Table 5-4.) Current standing committees are highlighted in yellow. The names of chairmen were taken from the Congressional Directory from 1816–1991. Four standing committees were founded before 1816. They were the Joint Committee on ENROLLED BILLS (established 1789), the joint Committee on the LIBRARY (established 1806), the Committee to AUDIT AND CONTROL THE CONTINGENT EXPENSES OF THE SENATE (established 1807), and the Committee on ENGROSSED BILLS (established 1810). The names of the chairmen of these committees for the years before 1816 were taken from the Annals of Congress. This list also enumerates the dates of establishment and termination of each committee. These dates were taken from Walter Stubbs, Congressional Committees, 1789–1982: A Checklist (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1985). There were eleven committees for which the dates of existence listed in Congressional Committees, 1789–1982 did not match the dates the committees were listed in the Congressional Directory. The committees are: ENGROSSED BILLS, ENROLLED BILLS, EXAMINE THE SEVERAL BRANCHES OF THE CIVIL SERVICE, Joint Committee on the LIBRARY OF CONGRESS, LIBRARY, PENSIONS, PUBLIC BUILDINGS AND GROUNDS, RETRENCHMENT, REVOLUTIONARY CLAIMS, ROADS AND CANALS, and the Select Committee to Revise the RULES of the Senate. For these committees, the dates are listed according to Congressional Committees, 1789– 1982, with a note next to the dates detailing the discrepancy. -

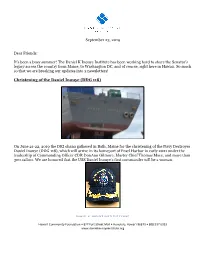

The Daniel K Inouye Institute Has Been Working Hard to Share the Senator's Legacy Across the Country from Maine, to Washington DC, and of Course, Right Here in Hawaii

September 23, 2019 Dear Friends: It's been a busy summer! The Daniel K Inouye Institute has been working hard to share the Senator's legacy across the country from Maine, to Washington DC, and of course, right here in Hawaii. So much so that we are breaking our updates into 2 newsletters! Christening of the Daniel Inouye (DDG 118) On June 21-22, 2019 the DKI ohana gathered in Bath, Maine for the christening of the Navy Destroyer Daniel Inouye (DDG 118), which will arrive in its homeport of Pearl Harbor in early 2021 under the leadership of Commanding Officer CDR DonAnn Gilmore, Master Chief Thomas Mace, and more than 300 sailors. We are honored that the USS Daniel Inouye’s first commander will be a woman. Hawai‘i Community Foundation • 827 Fort Street Mall • Honolulu, Hawai‘i 96813 • 808.537.6333 www.danielkinouyeinstitute.org Just getting to Maine was a monumental task! We deiced that a plastic lei on the DANIEL INOUYE just would not do, so we went to work. Thanks to support from Brion Chang and his team, 8 segments -- feet each, a massive ti-leaf lei (tied to a 1-inch diameter rope), which when assembled stretched 75 feet - a double strand lei. Watch this video to see the lei being assembled at the shipyard upon our arrival. https://youtu.be/XTi5d9OV0PU. The shipyard staff was eager to learn how to build the lei, and really enjoyed seeing the beautiful flowers. In addition, we brought 4 dozen lei for dignitaries, together with Big Island Candies, Kauai's special salt and a host of omiyage for special guests. -

A Brief History of the Hawaiian People

0 A BRIEF HISTORY OP 'Ill& HAWAIIAN PEOPLE ff W. D. ALEXANDER PUBLISHED BY ORDER OF THE BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE HAWAIIAN KINGDOM NEW YORK,: . CINCINNATI•:• CHICAGO AMERICAN BOOK C.OMPANY Digitized by Google ' .. HARVARD COLLEGELIBRAllY BEQUESTOF RCLANOBUr.ll,' , ,E DIXOII f,'.AY 19, 1936 0oPYBIGRT, 1891, BY AlilBIOAN BooK Co)[PA.NY. W. P. 2 1 Digit zed by Google \ PREFACE AT the request of the Board of Education, I have .fi. endeavored to write a simple and concise history of the Hawaiian people, which, it is hoped, may be useful to the teachers and higher classes in our schools. As there is, however, no book in existence that covers the whole ground, and as the earlier histories are entirely out of print, it has been deemed best to prepare not merely a school-book, but a history for the benefit of the general public. This book has been written in the intervals of a labo rious occupation, from the stand-point of a patriotic Hawaiian, for the young people of this country rather than for foreign readers. This fact will account for its local coloring, and for the prominence given to certain topics of local interest. Especial pains have been taken to supply the want of a correct account of the ancient civil polity and religion of the Hawaiian race. This history is not merely a compilation. It is based upon a careful study of the original authorities, the writer having had the use of the principal existing collections of Hawaiian manuscripts, and having examined the early archives of the government, as well as nearly all the existing materials in print. -

Congressional Record—Senate S7401

May 24, 1995 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — SENATE S7401 250th birthday of James Madison and land of Okinawa, he introduced it there A RETROSPECT OF V-E DAY honoring his many accomplishments. in 1910 and was the first master of the The surcharges raised from the selling Okinawan Karate-Do system. Mr. COCHRAN. Mr. President, an of the coins goes to the National Trust In 1956, for the first time, American issue of the journal entitled Uniformed for Historic Preservation for the cre- servicemen were accepted as students Services Journal, May-June 1995, con- ation of a permanent fund for the pres- in the Okinawan Karate-Do schools. tains an article entitled, ‘‘World War II ervation and renovation of Madison’s One of them settled in the Boston area Revisited: A Retrospect Of V-E Day home, Montpelier. after his military discharge and began and the Events Leading Up To It.’’ This is an important endeavor, Mr. teaching this art form to people in the The article includes recollections of President, because James Madison is area. Walter Mattson of Framingham, some of the distinguished Members of one of our nation’s most brilliant and MA, is the senior American instructor. the Congress who participated in World significant founding fathers. A Vir- Over the years, there has been a con- War II, among them Senator STROM ginian and a distinguished statesman, tinuing cultural exchange between the THURMOND, Senator BOB DOLE, Senator Madison was the principle drafter of Masters on Okinawa and practitioners DANIEL INOUYE, Congressmen TOM BE- the United States Constitution and the here in North America. -

Center for Hawaiian Sovereignty Studies 46-255 Kahuhipa St. Suite 1205 Kane'ohe, HI 96744 (808) 247-7942 Kenneth R

Center for Hawaiian Sovereignty Studies 46-255 Kahuhipa St. Suite 1205 Kane'ohe, HI 96744 (808) 247-7942 Kenneth R. Conklin, Ph.D. Executive Director e-mail [email protected] Unity, Equality, Aloha for all To: HOUSE COMMITTEE ON EDUCATION For hearing Thursday, March 18, 2021 Re: HCR179, HR148 URGING THE SUPERINTENDENT OF EDUCATION TO REQUEST THE BOARD OF EDUCATION TO CHANGE THE NAME OF PRESIDENT WILLIAM MCKINLEY HIGH SCHOOL BACK TO THE SCHOOL'S PREVIOUS NAME OF HONOLULU HIGH SCHOOL AND TO REMOVE THE STATUE OF PRESIDENT MCKINLEY FROM THE SCHOOL PREMISES TESTIMONY IN OPPOSITION There is only one reason why some activists want to abolish "McKinley" from the name of the school and remove his statue from the campus. The reason is, they want to rip the 50th star off the American flag and return Hawaii to its former status as an independent nation. And through this resolution they want to enlist you legislators as collaborators in their treasonous propaganda campaign. The strongest evidence that this is their motive is easy to see in the "whereas" clauses of this resolution and in documents provided by the NEA and the HSTA which are filled with historical falsehoods trashing the alleged U.S. "invasion" and "occupation" of Hawaii; alleged HCR179, HR148 Page !1 of !10 Conklin HSE EDN 031821 suppression of Hawaiian language and culture; and civics curriculum in the early Territorial period. Portraying Native Hawaiians as victims of colonial oppression and/or belligerent military occupation is designed to bolster demands to "give Hawaii back to the Hawaiians", thereby producing a race-supremacist government and turning the other 80% of Hawaii's people into second-class citizens. -

The Magnuson-Stevens Act a Bipartisan Legacy of Success

The Magnuson-Stevens Act A Bipartisan Legacy of Success Since 1976, when what is now called the Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act (MSA) was first signed into law, Republicans and Democrats have agreed that conserving America’s ocean fish makes good economic and environmental sense. Today, Congress should continue this tradition of bipartisan support for the MSA and preserve its legacy of success by opposing any efforts to weaken the law. Over the years, Congress has recognized the value of protecting ocean fish resources from overfishing (taking fish faster than they can reproduce) by providing managers with the legal tools to sustainably manage our nation’s ocean fisheries. Through Photo: Associated Press multiple reauthorizations, Congress President George W. Bush signs the Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation strengthened the MSA by mandating an end and Management Reauthorization Act of 2006, joined by Sen. Ted Stevens to overfishing through science-based annual (R-AK), left; Sen. Olympia Snowe (R-ME); Rep. Nick Rahall (D-WV); Rep. Jim Saxton (R-NJ); Rep. Frank Pallone (D-NJ), Rep. Don Young (R-AK); Commerce catch limits and also by requiring that depleted Secretary Carlos Gutierrez; and Rep. Wayne Gilchrest (R-MD). fish populations be rebuilt to healthy levels that can support thriving commercial and “This much-needed piece of legislation would enable our nation to protect recreational fisheries. Both Republicans and and conserve its enormously rich fishing resources.” Democrats have supported this law since —Sen. John Beall Jr. (R-MD), 1976 it was enacted more than 35 years ago. “Legislation such as this is desperately needed in order to preserve and manage our continued fishery resources.” In 1976, the Fishery Conservation and —Rep. -

From Exclusion to Inclusion

From Exclusion to Inclusion 1941–1992 Around 9 :00 in the morning on April 21, 1945, Daniel K. Inouye, a 20-year-old army lieutenant from Honolulu, Hawaii, was shot in the stomach on the side of a mountain in northwestern Italy. The German bullet went clean out his back and missed his spine by a fraction of an inch. “It felt like someone punched me,” he remembered years later. “But the pain was almost non-existent. A little ache, that’s all and since the bleeding was not much I said well, I’ll keep on going.”1 Later that morning, Inouye, a pre-med student who had been getting ready for church when Japan bombed Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, was hit again. This time a rifle grenade nearly blew off his entire right arm. After picking up his tommy gun with his left hand, he continued to charge up the hill, firing at German soldiers as he went. Eventually shot in the leg, Inouye waited until his men seized control of the mountain before being evacuated.2 The war in Europe ended 17 days later. Inouye lived in military hospitals for the next two years to rebuild his strength and learn to do everyday tasks with one arm. The war forced him to adapt, and over the next two decades, the country he nearly died for began to adapt to the war’s consequences as well. For the most marginalized people—women and minorities, especially—World War II had profound implications for what it meant to be American.