Radiocarbon Dating of Human Burials from Raqefet Cave And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Raqefet Cave: the 2006 Excavation Season

JournalTHE LATE of The NATUFIAN Israel Prehistoric AT RAQEFET Society CAVE 38 (2008), 59-131 59 The Late Natufian at Raqefet Cave: The 2006 Excavation Season DANI NADEL1 GYORGY LENGYEL1,2 FANNY BOCQUENTIN3 ALEXANDER TSATSKIN1 DANNY ROSENBERG1 REUVEN YESHURUN1 GUY BAR-OZ1 DANIELLA E. BAR-YOSEF MAYER4 RON BEERI1 LAURENCE CONYERS5 SAGI FILIN6 ISRAEL HERSHKOVITZ7 ALDONA KURZAWSKA8 LIOR WEISSBROD1 1 Zinman Institute of Archaeology, the University of Haifa, 31905 Mt. Carmel, Israel 2 Faculty of Arts, Institute of Historical Sciences, Department of Prehistory and Ancient History. University of Miskolc, 3515 Miskolc, Miskolc-Egyetemvros, Hungary 3 UMR 7041 du CNRS, Ethnologie Préhistorique, 21 Allée de l’Université, F-92023 Nanterre Cedex, France 4 Department of Maritime Civilizations and The Leon Recanati Institute for Maritime Studies, University of Haifa, Israel 5 Department of Anthropology, University of Denver, Denver, Colorado, USA 6 Department of Transportation and Geo-Information Engineering, Technion – Israel Institute of Technology, Haifa 32000, Israel 7 Sackler School of Medicine, Tel Aviv University, Israel 8 Institute of Archaeology and Ethnology, Polish Academy of Sciences, Poznan Branch, Poland 59 60 NADEL D. et al. ABSTRACT A long season of excavation took place at Raqefet cave during the summer of 2006. In the first chamber we exposed an area rich with Natufian human burials (Locus 1), a large bedrock basin with a burial and two boulder mortars (Locus 2), an in situ Natufian layer (Locus 3), and two areas with rich cemented sediments (tufa) covering the cave floor (Loci 4, 5). The latter indicate that at the time of occupation the Natufian layers covered the entire floor of the first chamber. -

A B S T Ra C T S O F T H E O Ra L and Poster Presentations

Abstracts of the oral and poster presentations (in alphabetic order) see Addenda, p. 271 11th ICAZ International Conference. Paris, 23-28 August 2010 81 82 11th ICAZ International Conference. Paris, 23-28 August 2010 ABRAMS Grégory1, BONJEAN ABUHELALEH Bellal1, AL NAHAR Maysoon2, Dominique1, Di Modica Kévin1 & PATOU- BERRUTI Gabriele Luigi Francesco, MATHIS Marylène2 CANCELLIERI Emanuele1 & THUN 1, Centre de recherches de la grotte Scladina, 339D Rue Fond des Vaux, 5300 Andenne, HOHENSTEIN Ursula1 Belgique, [email protected]; [email protected] ; [email protected] 2, Institut de Paléontologie Humaine, Département Préhistoire du Muséum National d’Histoire 1, Department of Biology and Evolution, University of Ferrara, Corso Ercole I d’Este 32, Ferrara Naturelle, 1 Rue René Panhard, 75013 Paris, France, [email protected] (FE: 44100), Italy, [email protected] 2, Department of Archaeology, University of Jordan. Amman 11942 Jordan, maysnahar@gmail. com Les os brûlés de l’ensemble sédimentaire 1A de Scladina (Andenne, Belgique) : apports naturels ou restes de foyer Study of Bone artefacts and use techniques from the Neo- néandertalien ? lithic Jordanian site; Tell Abu Suwwan (PPNB-PN) L’ensemble sédimentaire 1A de la grotte Scladina, daté par 14C entre In this paper we would like to present the experimental study car- 40 et 37.000 B.P., recèle les traces d’une occupation par les Néan- ried out in order to reproduce the bone artifacts coming from the dertaliens qui contient environ 3.500 artefacts lithiques ainsi que Neolithic site Tell Abu Suwwan-Jordan. This experimental project plusieurs milliers de restes fauniques, attribués majoritairement au aims to complete the archaeozoological analysis of the bone arti- Cheval pour les herbivores. -

Paleoanthropology Society Meeting Abstracts, Memphis, Tn, 17-18 April 2012

PALEOANTHROPOLOGY SOCIETY MEETING ABSTRACTS, MEMPHIS, TN, 17-18 APRIL 2012 Paleolithic Foragers of the Hrazdan Gorge, Armenia Daniel Adler, Anthropology, University of Connecticut, USA B. Yeritsyan, Archaeology, Institute of Archaeology & Ethnography, ARMENIA K. Wilkinson, Archaeology, Winchester University, UNITED KINGDOM R. Pinhasi, Archaeology, UC Cork, IRELAND B. Gasparyan, Archaeology, Institute of Archaeology & Ethnography, ARMENIA For more than a century numerous archaeological sites attributed to the Middle Paleolithic have been investigated in the Southern Caucasus, but to date few have been excavated, analyzed, or dated using modern techniques. Thus only a handful of sites provide the contextual data necessary to address evolutionary questions regarding regional hominin adaptations and life-ways. This talk will consider current archaeological research in the Southern Caucasus, specifically that being conducted in the Republic of Armenia. While the relative frequency of well-studied Middle Paleolithic sites in the Southern Caucasus is low, those considered in this talk, Nor Geghi 1 (late Middle Pleistocene) and Lusakert Cave 1 (Upper Pleistocene), span a variety of environmental, temporal, and cultural contexts that provide fragmentary glimpses into what were complex and evolving patterns of subsistence, settlement, and mobility over the last ~200,000 years. While a sample of two sites is too small to attempt a serious reconstruction of Middle Paleolithic life-ways across such a vast and environmentally diverse region, the sites -

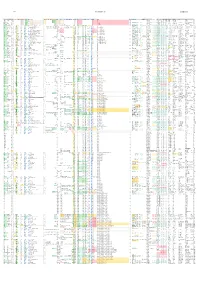

Ancient DNA Dataset 2.07.72

8/27/2021 Ancient DNA Dataset 2.07.72 https://haplogroup.info/ Object‐ID Colloquial‐Skeletal LatitudLongit Sex mtDNA‐comtFARmtDNA‐haplogroup mtDNA‐Haplotree mt‐FT mtree mt‐YFFTDNA‐mt‐Haplotree mt‐Simmt‐S HVS‐I HVS‐II HVS‐NO mt‐SNPs Responsible‐ Y‐DNA Y‐New SNP‐positive SNP‐negative SNP‐dubious NRY Y‐FARY‐Simple YTree Y‐Haplotree‐VY‐Haplotree‐PY‐FTD YFull Y‐YFu ISOGG2019 FTDNA‐Y‐Haplotree Y‐SymY‐Symbol2Responsible‐SNPSNPs AutosomaDamage‐RAssessmenKinship‐Notes Source Method‐Date Date Mean CalBC_top CalBC_bot Age Simplified_Culture Culture_Grouping Label Location SiteID Country Denisova4 FR695060.1 51.4 84.7 M DN1a1 DN1a1 https:/ROOT>HD>DN1>D1a>D1a1 DN L A11914G • C1YFull TMRCA ca. 708,133.1 (549,422.5‐930,979.7) A0000 A0000 A0000 A0000 A0 A0000 PetrbioRxiv2020 84.1–55.2 ka [Douka ‐67700 ‐82150 ‐53250 Adult ma Denisovan Middle Palaeolithic Denisova Cave Russia Denisova8 KT780370.1 51.4 84.7 M DN2 DN2 https:/ROOT>HD>DN2 DN L A11914G • C1YFull TMRCA ca. 706,874.9 (607,187.2‐833,211.4) A0000 A0000‐T A0000‐T A0000‐T A0 A0000 PetrbioRxiv2020 136.4–105.6 ka ‐119050 ‐134450 ‐103650 Adult ma Denisovan Middle Palaeolithic Denisova Cave Russia Spy_final Spy 94a 50.5 4.67 .. ND1b1a1b2* ND1b1a1b2* https:/ROOT>NM>ND>ND1>ND1b>ND1b1>ND1b1a>ND1b1a1>ND1b1a1b>ND1b1a1b2 ND L C6563T * A11YFull TMRCA ca. 369,637.7 (326,137.1‐419,311.0) A000 A000a A000a A000‐T>A000>A000a A0 A000 PetrbioRxiv2020 553719 0.66381 .. PASS (literan/a HajdinjakNature2018 from MeyDirect: 95.4%; IntCal20, OxC39431‐38495 calBCE ‐38972 ‐39431 ‐38495 Neanderthal Late Middle Palaeolithic Spy_Neanderthal.SG Grotte de Spy, Jemeppe‐sur‐Sambre, Namur Belgium El Sidron 1253 FM865409.1 43.4 ‐5.33 ND1b1a* ND1b1a* https:/ROOT>NM>ND>ND1>ND1b>ND1b1>ND1b1a ND L YFull TMRCA ca. -

Human Origin Sites and the World Heritage Convention in Eurasia

World Heritage papers41 HEADWORLD HERITAGES 4 Human Origin Sites and the World Heritage Convention in Eurasia VOLUME I In support of UNESCO’s 70th Anniversary Celebrations United Nations [ Cultural Organization Human Origin Sites and the World Heritage Convention in Eurasia Nuria Sanz, Editor General Coordinator of HEADS Programme on Human Evolution HEADS 4 VOLUME I Published in 2015 by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, 7, place de Fontenoy, 75352 Paris 07 SP, France and the UNESCO Office in Mexico, Presidente Masaryk 526, Polanco, Miguel Hidalgo, 11550 Ciudad de Mexico, D.F., Mexico. © UNESCO 2015 ISBN 978-92-3-100107-9 This publication is available in Open Access under the Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO (CC-BY-SA 3.0 IGO) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/igo/). By using the content of this publication, the users accept to be bound by the terms of use of the UNESCO Open Access Repository (http://www.unesco.org/open-access/terms-use-ccbysa-en). The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNESCO concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The ideas and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors; they are not necessarily those of UNESCO and do not commit the Organization. Cover Photos: Top: Hohle Fels excavation. © Harry Vetter bottom (from left to right): Petroglyphs from Sikachi-Alyan rock art site. -

LAMPEA-Doc 2013 – Numéro 26 Vendredi 19 Juillet 2013 [Se Désabonner >>>]

Laboratoire méditerranéen de Préhistoire (Europe – Afrique) Bibliothèque LAMPEA-Doc 2013 – numéro 26 vendredi 19 juillet 2013 [Se désabonner >>>] Suivez les infos en continu en vous abonnant au fil RSS http://sites.univ-provence.fr/lampea/spip.php?page=backend 1 - Actu - Fouille d'un important habitat néolithique à Vernègues – Cazan (Bouches- du-Rhône) 2 - Appel à candidatures - La Maison des Sciences de l’Homme de Montpellier lance un appel à programmes 3 - Congrès, colloques, réunions - 1839ème Réunion scientifique de la Société d'Anthropologie de Paris - Cinquième Rencontre sur la Valorisation et la Préservation du Patrimoine Paléontologique (RV3P5) - 3rd annual meeting of the European Society for the study of Human Evolution (ESHE) 4 - Emplois, bourses, prix - La Ville de Lyon recrute un-e archéologue - Mise au concours d’un poste à Tübingen ... sur la Bourgogne - Mosaïques Archéologie recherche un(e) responsable d'opération néolithicien(ne) - Assistant Ingénieur en Humanités Numériques - Vu sur le site de la Bourse interministérielle des Emplois publics ... - Junior scientist position in luminescence dating (OSL) 5 - Expositions & animations - Randonnées-Découvertes « Sur les chemins de Cro-Magnon » 6 - Acquisitions bibliothèque DomCom/19.07.2013 Ce soir ! Séminaire, conférence La grotte ornée et sépulcrale de Cussac : premier bilan de 4 années de recherche par Jacques Jaubert http://sites.univ-provence.fr/lampea/spip.php?article2313 vendredi 19 juillet à 18 heures 30 Les Eyzies-de-Tayac La semaine prochaine Voir « Les manifestations » http://sites.univ-provence.fr/lampea/spip.php?article630 1 - Actu Fouille d'un important habitat néolithique à Vernègues – Cazan (Bouches-du- Rhône) http://sites.univ-provence.fr/lampea/spip.php?article2319 À Cazan, sur la commune de Vernègues et en bordure de la nationale 7, une fouille archéologique qui a duré trois mois vient de s'achever le 31 mai dernier. -

Back to Raqefet Cave, Mount Carmel, Israel

Journal of The Israel Prehistoric Society 35 (2005), 245-270 Back to Raqefet Cave, Mount Carmel, Israel GYÖRGY LENGYEL*1 DANI NADEL*1 ALEXANDER TSATSKIN1 GUY BAR-OZ1 DANIELLA E. BAR-YOSEF MAYER1 RON BEʼERI1 ISRAEL HERSHKOVITZ2 1Zinman Institute of Archaeology, University of Haifa, 31905 Mount Carmel, Haifa, Israel 2Sackler School of Medicine, Tel Aviv University *Contributed equally to the paper INTRODUCTION The Raqefet Cave was excavated some thirty years ago by the late Tamar Noy and Eric Higgs (herein the 1970-72 excavation). Unfortunately, although they found a long cultural sequence and several Natufian burials, they hardly publish any details of their fieldwork or the stratigraphy. In the summer of 2004 we carried out a short reconnaissance project, in order to clean the main section and verify the unpublished stratigraphy (we have the original field documentations); establish the provenance of Early Upper Palaeolithic, Levantine Aurignacian and Epipalaeolithic (Late Kebaran) lithic assemblages; and asses the character of the Natufian layer. The aims of this paper are to a) provide a short description of past work at the site (based on an unpublished report and the Raqefet Archive) and list the main studies conducted on the retrieved materials, and b) present the results of our short fieldwork. The latter include a report on the Natufian remains in the first chamber and a description of the long section in the second 245 246 LENGYEL et. al. chamber. Studied samples of flint, animal bones and beads are also presented. Depositional and post-depositional aspects are addressed through preliminary sedimentological studies and taphonomic observations on a sample of the 1970-72 animal bones. -

Book of Abstracts

Book of abstracts XVIII° CONGRES UISPP PARIS JUIN 2018 18th UISPP WORLD CONGRESS, PARIS, JUNE 2018 1 Table of contents XVIIIe congres UISPP Paris.pdf1 IV-1. Old Stones, New Eyes? Charting future directions in lithic analysis. 10 Found Objects and Readymade in the Lower Palaeolithic: Selection and Col- lection of Fully Patinated Flaked Items for Shaping Scrapers at Qesem Cave, Israel, Bar Efrati [et al.]................................ 11 Lithic technology as part of the `human landscape': an alternative view, Simon Holdaway........................................ 13 Moving on from here: the evolving role of mobility in studies of Paleolithic tech- nology., Steven Kuhn.................................. 14 The settlement system of Mount Carmel (Israel) at the threshold of agriculture as reflected in Late Natufian flint assemblages, Gal Bermatov-Paz [et al.]..... 15 What lithic technology (really) wants. An alternative "life-theoretical" perspec- tive on technological evolution in the deep past, Shumon Hussain......... 16 Exploring knowledge-transfer systems during the Still Bay at 80-70 thousand years ago in southern Africa, Marlize Lombard [et al.]............... 17 Technological Choices along the Early Natufian Sequence of el-Wad Terrace, Mount Carmel, Israel, false [et al.].......................... 18 Trying the old and the new: Combining approaches to lithic analysis, Aldo Malag´o[et al.]...................................... 19 Early tool-making and the biological evolution of memory systems in brains of early Homo., Michael Walker............................. 21 New methodology for studying old lithics to answer new questions: about the laterality in human evolution., Am`eliaBargall´o[et al.]............... 23 1 Approaches and limits of core classification systems and new perspectives, Jens Frick [et al.]....................................... 24 On the application of 3D analysis to the definition of lithic technological tradi- tion, Francesco Valletta [et al.]........................... -

A Grid-Like Incised Pattern Inside a Natufian Bedrock Mortar, Raqefet Cave, Israel Dani Nadel 1, Danny Rosenberg 2

A grid-like incised pattern inside a Natufian bedrock mortar, Raqefet Cave, Israel Dani Nadel 1, Danny Rosenberg 2 1. Zinman Institute of Archaeology, University of Haifa, Mount Carmel, 3498898 Haifa, Israel. Email: [email protected] 2. Laboratory for Ground Stone Tools Research, Zinman Institute of Archaeology, University of Haifa, Mount Carmel, 3498898 Haifa, Israel. Email: [email protected] Abstract: Bedrock features are a hallmark of the Natufian (ca. 15,000-11,500 cal BP) in the southern Levant and beyond and they include a large variety of types, from deep variants to shallow ones and from narrow mortars to wide basins. They are usually interpreted as food preparation facilities, associated with Natufian intensification of cereal and acorn consumption. However, inside the shaft of one deep narrow Natufian mortar at the entrance to Raqefet Cave (Mt. Carmel, Israel), we found a set of grid-like incisions accompanied by irregular lines. This pattern is similar in the general impression and the details of execution to incised stone slabs and objects found in other Natufian sites. As in several other Natufian objects, the incised patterns were hardly visible at the time, due to their light appearance and concealed location. The engraving act and symbolic meaning of the contents were likely more important than the display of the results. Furthermore, the Raqefet mortar was incorporated in a structured complex that also included a slab pavement and a boulder mortar. Thus, the complex motif, the specific feature it was carved on (inside a deep mortar), the associated features, and the location at the entrance to a burial cave all suggest an elaborate ceremonial and symbolic system. -

Meetings Version of the Paleoanthropology Abstracts

Meetings Version of the Paleoanthropology Abstracts Memphis, TN, 17–18 April 2012 (Please note that the Meetings Version is not the official publication and most copy editing is not yet done; abstracts will be published in our on-line journal, PaleoAnthropology, in May 2012) Adler et al. Paleolithic Foragers of the Hrazdan Gorge, Armenia For more than a century numerous archaeological sites attributed to the Middle Paleolithic have been investigated in the Southern Caucasus, but to date few have been excavated, analyzed, or dated using modern techniques. Thus only a handful of sites provide the contextual data necessary to address evolutionary questions regarding regional hominin adaptations and life-ways. This talk will consider current archaeological research in the Southern Caucasus, specifically that being conducted in the Republic of Armenia. While the relative frequency of well-studied Middle Paleolithic sites in the Southern Caucasus is low, those considered in this talk, Nor Geghi 1 (late Middle Pleistocene) and Lusakert Cave 1 (Upper Pleistocene), span a variety of environmental, temporal, and cultural contexts that provide fragmentary glimpses into what were complex and evolving patterns of subsistence, settlement, and mobility over the last ~200,000 years. While a sample of two sites is too small to attempt a serious reconstruction of Middle Paleolithic life-ways across such a vast and environmentally diverse region, the sites discussed here provide initial glimpses into the technological, economic, and social behaviors of perhaps the earliest, and certainly the latest Middle Paleolithic hominins in the Southern Caucasus. Aldeias et al. On the Use of Hearths as a Tool for Reconstructing Middle Paleolithic Spatial Organization Based on ethnographic and archaeological research, hearths have long been seen as a kind of anchor around which spatial organization and behavioral activities of modern and past hunter-gatherer communities are organized. -

Palaeogenomic and Biostatistical Analysis of Ancient DNA Data from Mesolithic and Neolithic Skeletal Remains

Palaeogenomic and Biostatistical Analysis of Ancient DNA Data from Mesolithic and Neolithic Skeletal Remains Dissertation submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree Doktor der Naturwissenschaften at Faculty of Biology Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz Zuzana Hofmanov´a Mainz, 2016 Abstract Palaeogenomic data have illuminated several important periods of human past with surprising im- plications for our understanding of human evolution. One of the major changes in human prehistory was Neolithisation, the introduction of the farming lifestyle to human societies. Farming originated in the Fertile Crescent approximately 10,000 years BC and in Europe it was associated with a major population turnover. Ancient DNA from Anatolia, the presumed source area of the demic spread to Europe, and the Balkans, one of the first known contact zones between local hunter-gatherers and incoming farmers, was obtained from roughly contemporaneous human remains dated to ∼6th mil- lennium BC. This new unprecedented dataset comprised of 86 full mitogenomes, five whole genomes (7.1–3.7x coverage) and 20 high coverage (7.6–93.8x) genomic samples. The Aegean Neolithic pop- ulation, relatively homogeneous on both sides of the Aegean Sea, was positively proven to be a core zone for demic spread of farmers to Europe. The farmers were shown to migrate through the central Balkans and while the local sedentary hunter-gathers of Vlasac in the Danube Gorges seemed to be isolated from the farmers coming from the south, the individuals of the Aegean origin infiltrated the nearby hunter-gatherer community of Lepenski Vir. The intensity of infiltration increased over time and even though there was an impact of the Danubian hunter-gatherers on genetic variation of Neolithic central Europe, the Aegean ancestry dominated during the introduction of farming to the continent. -

Civis Agricola

Civis agricola EN ASIA, EUROPA, AMÉRICA, OCEANÍA, Y ÁFRICA, DESDE EL ÚLTIMO MÁXIMO GLACIAL, SOCIEDADES ITINERANTES ADOPTARON VIDA SEDENTARIA PERMANENTE PARA EVOLUCIONAR ECONOMÍAS AGRÍCOLAS Canis lupus A. F. MARTIN 2021 Contracubierta: Figura del Arte Rupestre de Coahuila, Mexico -Sierra de Jimulco, Gruta La Gualdria- Civis agricola EN ASIA, EUROPA, AMÉRICA, OCEANÍA, Y ÁFRICA, DESDE EL ÚLTIMO MÁXIMO GLACIAL, SOCIEDADES ITINERANTES ADOPTARON VIDA SEDENTARIA PERMANENTE PARA EVOLUCIONAR ECONOMÍAS AGRÍCOLAS Columba palumbus -Kensington Gardens, London- A. F. Martin, 2014-2021 Programa Exordio Canis lupus familiaris Agricultura y selección de plantas. La economía agrícola Domesticación Último Máximo Glacial Canis lupus familiaris Conocimiento de los cereales, y elaboración de harinas Europa Este Asia -Ohalo II- China La vida sedentaria y la adopción progresiva de la economía agrícola Younger Dryas Adopción de la agricultura ASIA Suroeste Asia Levante Anatolia Irán India Quinghai Tibet Plateau Norte China Sur China Central Asia Kazakhstan La Ruta de La Seda Arabia EUROPA AMÉRICA Brasil Andes -Perú- Mesoamérica Norte América OCEANÍA Australasia Melanesia Micronesia Polinesia ÁFRICA Este África Transferencias marítimas a Este África Transferencias terrestres a África Sahara Oeste África Marruecos Zuid-Africa Domesticidad Mus musculus Passer domesticus Felis silvestris catus Domesticación Bos primigenius taurus -Toro- Bos primigenius indicus -Cebú- Bos grunniens -Yak- Sus scrofa domestica -Puerco- Capra hircus -Chivo- Ovis aries -Cordero- Gallus gallus domesticus -Gallo- Equus caballus -Caballo- Equus africanus asinus -Asno- Lama glama -Llama- Vicugna pacos -Alpaca- Taurotragus oryx -Eland Común- Selección de caractéres adaptativos para la agricultura Oryza rufipogon -Arroz- Hordeum spontaneum -Cebada- Hordeum vulgare ssp. vulgare var. hexastichon v Triticum dicoccum -Farro- Triticum monococcum -Escanda- Triticum aestivum -Trigo Vulgar- Triticum araraticum Zea mays parviglumis -Maíz- Solanum sp.