Epipalaeolithic and Pre-Pottery Neolithic Burials from the North Lebanese Highlands in Their Regional Context Andrew Garrard1, Y

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Raqefet Cave: the 2006 Excavation Season

JournalTHE LATE of The NATUFIAN Israel Prehistoric AT RAQEFET Society CAVE 38 (2008), 59-131 59 The Late Natufian at Raqefet Cave: The 2006 Excavation Season DANI NADEL1 GYORGY LENGYEL1,2 FANNY BOCQUENTIN3 ALEXANDER TSATSKIN1 DANNY ROSENBERG1 REUVEN YESHURUN1 GUY BAR-OZ1 DANIELLA E. BAR-YOSEF MAYER4 RON BEERI1 LAURENCE CONYERS5 SAGI FILIN6 ISRAEL HERSHKOVITZ7 ALDONA KURZAWSKA8 LIOR WEISSBROD1 1 Zinman Institute of Archaeology, the University of Haifa, 31905 Mt. Carmel, Israel 2 Faculty of Arts, Institute of Historical Sciences, Department of Prehistory and Ancient History. University of Miskolc, 3515 Miskolc, Miskolc-Egyetemvros, Hungary 3 UMR 7041 du CNRS, Ethnologie Préhistorique, 21 Allée de l’Université, F-92023 Nanterre Cedex, France 4 Department of Maritime Civilizations and The Leon Recanati Institute for Maritime Studies, University of Haifa, Israel 5 Department of Anthropology, University of Denver, Denver, Colorado, USA 6 Department of Transportation and Geo-Information Engineering, Technion – Israel Institute of Technology, Haifa 32000, Israel 7 Sackler School of Medicine, Tel Aviv University, Israel 8 Institute of Archaeology and Ethnology, Polish Academy of Sciences, Poznan Branch, Poland 59 60 NADEL D. et al. ABSTRACT A long season of excavation took place at Raqefet cave during the summer of 2006. In the first chamber we exposed an area rich with Natufian human burials (Locus 1), a large bedrock basin with a burial and two boulder mortars (Locus 2), an in situ Natufian layer (Locus 3), and two areas with rich cemented sediments (tufa) covering the cave floor (Loci 4, 5). The latter indicate that at the time of occupation the Natufian layers covered the entire floor of the first chamber. -

A B S T Ra C T S O F T H E O Ra L and Poster Presentations

Abstracts of the oral and poster presentations (in alphabetic order) see Addenda, p. 271 11th ICAZ International Conference. Paris, 23-28 August 2010 81 82 11th ICAZ International Conference. Paris, 23-28 August 2010 ABRAMS Grégory1, BONJEAN ABUHELALEH Bellal1, AL NAHAR Maysoon2, Dominique1, Di Modica Kévin1 & PATOU- BERRUTI Gabriele Luigi Francesco, MATHIS Marylène2 CANCELLIERI Emanuele1 & THUN 1, Centre de recherches de la grotte Scladina, 339D Rue Fond des Vaux, 5300 Andenne, HOHENSTEIN Ursula1 Belgique, [email protected]; [email protected] ; [email protected] 2, Institut de Paléontologie Humaine, Département Préhistoire du Muséum National d’Histoire 1, Department of Biology and Evolution, University of Ferrara, Corso Ercole I d’Este 32, Ferrara Naturelle, 1 Rue René Panhard, 75013 Paris, France, [email protected] (FE: 44100), Italy, [email protected] 2, Department of Archaeology, University of Jordan. Amman 11942 Jordan, maysnahar@gmail. com Les os brûlés de l’ensemble sédimentaire 1A de Scladina (Andenne, Belgique) : apports naturels ou restes de foyer Study of Bone artefacts and use techniques from the Neo- néandertalien ? lithic Jordanian site; Tell Abu Suwwan (PPNB-PN) L’ensemble sédimentaire 1A de la grotte Scladina, daté par 14C entre In this paper we would like to present the experimental study car- 40 et 37.000 B.P., recèle les traces d’une occupation par les Néan- ried out in order to reproduce the bone artifacts coming from the dertaliens qui contient environ 3.500 artefacts lithiques ainsi que Neolithic site Tell Abu Suwwan-Jordan. This experimental project plusieurs milliers de restes fauniques, attribués majoritairement au aims to complete the archaeozoological analysis of the bone arti- Cheval pour les herbivores. -

Yeroshevich Et Al.Design

Design and Performance of Microlith Implemented Projectiles During the Middle and the Late Epipaleolithic of the Levant: Experimental and Archaeological Evidence The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Yaroshevich Alla, Daniel Kaufman , Dnitri Nuzhnyy, Ofer Bar- Yosef, and Mina Weinstein-Evron. 2010. Design and performance of microlith implemented projectiles during the middle and the late Epipaleolithic of the Levant: Experimental and archaeological evidence. Journal of Archaeological Science 37(2): 368-388. Published Version doi:10.1016/j.jas.2009.09.050 Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:4270545 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Open Access Policy Articles, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#OAP 1 Design and Performance of Microlith Implemented Projectiles During the Middle and the Late Epipaleolithic of the Levant: Experimental and Archaeological Evidence Alla Yaroshevich 1,2, Daniel Kaufman3, Dmitri Nuzhnyy4, Ofer Bar-Yosef5, Mina Weinstein-Evron3 1 University of Haifa, Department of Archaeology, Israel 2 Israel Antiquities Authority 3 Zinman Institute of Archaeology, University of Haifa, Israel 4 Institute of Archaeology, National Academy of Science, Kiev, Ukraine 5 Harvard University, Department of Anthropology, Peabody Museum of Archeology and Ethnology, USA Abstract The study comprises an experimentally based investigation of interaction between temporal change in the morphology of microlithic tools and transformations in projectile technology during the Late Pleistocene in the Levant. -

Paleoanthropology Society Meeting Abstracts, Memphis, Tn, 17-18 April 2012

PALEOANTHROPOLOGY SOCIETY MEETING ABSTRACTS, MEMPHIS, TN, 17-18 APRIL 2012 Paleolithic Foragers of the Hrazdan Gorge, Armenia Daniel Adler, Anthropology, University of Connecticut, USA B. Yeritsyan, Archaeology, Institute of Archaeology & Ethnography, ARMENIA K. Wilkinson, Archaeology, Winchester University, UNITED KINGDOM R. Pinhasi, Archaeology, UC Cork, IRELAND B. Gasparyan, Archaeology, Institute of Archaeology & Ethnography, ARMENIA For more than a century numerous archaeological sites attributed to the Middle Paleolithic have been investigated in the Southern Caucasus, but to date few have been excavated, analyzed, or dated using modern techniques. Thus only a handful of sites provide the contextual data necessary to address evolutionary questions regarding regional hominin adaptations and life-ways. This talk will consider current archaeological research in the Southern Caucasus, specifically that being conducted in the Republic of Armenia. While the relative frequency of well-studied Middle Paleolithic sites in the Southern Caucasus is low, those considered in this talk, Nor Geghi 1 (late Middle Pleistocene) and Lusakert Cave 1 (Upper Pleistocene), span a variety of environmental, temporal, and cultural contexts that provide fragmentary glimpses into what were complex and evolving patterns of subsistence, settlement, and mobility over the last ~200,000 years. While a sample of two sites is too small to attempt a serious reconstruction of Middle Paleolithic life-ways across such a vast and environmentally diverse region, the sites -

The KHALUB-Tree in Mesopotamia: Myth Or Reality?

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons University of Pennsylvania Museum of University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology Papers Archaeology and Anthropology 2009 The KHALUB-tree in Mesopotamia: Myth or Reality? Naomi F. Miller University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Alhena Gadotti Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/penn_museum_papers Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation (OVERRIDE) Miller, N.F. & Gadotti, A. (2009). The KHALUB-tree in Mesopotamia: Myth or Reality? In A.S. Fairbairn & E. Weiss (Eds.). From Foragers to Farmers: Gordon C. Hillman Festschrift (pp. 239-243). Oxford: Oxbow Books. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/penn_museum_papers/21 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The KHALUB-tree in Mesopotamia: Myth or Reality? Disciplines Archaeological Anthropology This book chapter is available at ScholarlyCommons: https://repository.upenn.edu/penn_museum_papers/21 This pdf of your paper in Foragers and Farmers belongs to the publishers Oxbow Books and it is their copyright. As author you are licenced to make up to 50 offprints from it, but beyond that you may not publish it on the World Wide Web until three years from publication (June 20 12), unless the site is a limited access intranet (pass word protected). If you have queries about this please contact the editorial department at Oxbow Books ([email protected]). An Offprint from FRoM FoRAGERS TO FARMERS GoRDON C. HILLMAN FESTSCHRIFT Edited by AndrewS. Fairbairn and Ehud Weiss OXBOW BOOKS Oxford and Oakville Contents Introduction: In honour of Professor Gordon C. Hillman .... ........... ....... ............. .. ... .. ....................... ... .......... .. ... vn Publications of Gordon C. -

© in This Web Service Cambridge University

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-01829-7 - Human Adaptation in the Asian Palaeolithic: Hominin Dispersal and Behaviour during the Late Quaternary Ryan J. Rabett Index More information Index Abdur, 88 Arborophilia sp., 219 Abri Pataud, 76 Arctictis binturong, 218, 229, 230, 231, 263 Accipiter trivirgatus,cf.,219 Arctogalidia trivirgata, 229 Acclimatization, 2, 7, 268, 271 Arctonyx collaris, 241 Acculturation, 70, 279, 288 Arcy-sur-Cure, 75 Acheulean, 26, 27, 28, 29, 45, 47, 48, 51, 52, 58, 88 Arius sp., 219 Acheulo-Yabrudian, 48 Asian leaf turtle. See Cyclemys dentata Adaptation Asian soft-shell turtle. See Amyda cartilaginea high frequency processes, 286 Asian wild dog. See Cuon alipinus hominin adaptive trajectories, 7, 267, 268 Assamese macaque. See Macaca assamensis low frequency processes, 286–287 Athapaskan, 278 tropical foragers (Southeast Asia), 283 Atlantic thermohaline circulation (THC), 23–24 Variability selection hypothesis, 285–286 Attirampakkam, 106 Additive strategies Aurignacian, 69, 71, 72, 73, 76, 78, 102, 103, 268, 272 economic, 274, 280. See Strategy-switching Developed-, 280 (economic) Proto-, 70, 78 technological, 165, 206, 283, 289 Australo-Melanesian population, 109, 116 Agassi, Lake, 285 Australopithecines (robust), 286 Ahmarian, 80 Azilian, 74 Ailuropoda melanoleuca fovealis, 35 Airstrip Mound site, 136 Bacsonian, 188, 192, 194 Altai Mountains, 50, 51, 94, 103 Balobok rock-shelter, 159 Altamira, 73 Ban Don Mun, 54 Amyda cartilaginea, 218, 230 Ban Lum Khao, 164, 165 Amyda sp., 37 Ban Mae Tha, 54 Anderson, D.D., 111, 201 Ban Rai, 203 Anorrhinus galeritus, 219 Banteng. See Bos cf. javanicus Anthracoceros coronatus, 219 Banyan Valley Cave, 201 Anthracoceros malayanus, 219 Barranco Leon,´ 29 Anthropocene, 8, 9, 274, 286, 289 BAT 1, 173, 174 Aq Kupruk, 104, 105 BAT 2, 173 Arboreal-adapted taxa, 96, 110, 111, 113, 122, 151, 152, Bat hawk. -

Ancient DNA Dataset 2.07.72

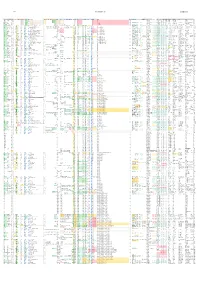

8/27/2021 Ancient DNA Dataset 2.07.72 https://haplogroup.info/ Object‐ID Colloquial‐Skeletal LatitudLongit Sex mtDNA‐comtFARmtDNA‐haplogroup mtDNA‐Haplotree mt‐FT mtree mt‐YFFTDNA‐mt‐Haplotree mt‐Simmt‐S HVS‐I HVS‐II HVS‐NO mt‐SNPs Responsible‐ Y‐DNA Y‐New SNP‐positive SNP‐negative SNP‐dubious NRY Y‐FARY‐Simple YTree Y‐Haplotree‐VY‐Haplotree‐PY‐FTD YFull Y‐YFu ISOGG2019 FTDNA‐Y‐Haplotree Y‐SymY‐Symbol2Responsible‐SNPSNPs AutosomaDamage‐RAssessmenKinship‐Notes Source Method‐Date Date Mean CalBC_top CalBC_bot Age Simplified_Culture Culture_Grouping Label Location SiteID Country Denisova4 FR695060.1 51.4 84.7 M DN1a1 DN1a1 https:/ROOT>HD>DN1>D1a>D1a1 DN L A11914G • C1YFull TMRCA ca. 708,133.1 (549,422.5‐930,979.7) A0000 A0000 A0000 A0000 A0 A0000 PetrbioRxiv2020 84.1–55.2 ka [Douka ‐67700 ‐82150 ‐53250 Adult ma Denisovan Middle Palaeolithic Denisova Cave Russia Denisova8 KT780370.1 51.4 84.7 M DN2 DN2 https:/ROOT>HD>DN2 DN L A11914G • C1YFull TMRCA ca. 706,874.9 (607,187.2‐833,211.4) A0000 A0000‐T A0000‐T A0000‐T A0 A0000 PetrbioRxiv2020 136.4–105.6 ka ‐119050 ‐134450 ‐103650 Adult ma Denisovan Middle Palaeolithic Denisova Cave Russia Spy_final Spy 94a 50.5 4.67 .. ND1b1a1b2* ND1b1a1b2* https:/ROOT>NM>ND>ND1>ND1b>ND1b1>ND1b1a>ND1b1a1>ND1b1a1b>ND1b1a1b2 ND L C6563T * A11YFull TMRCA ca. 369,637.7 (326,137.1‐419,311.0) A000 A000a A000a A000‐T>A000>A000a A0 A000 PetrbioRxiv2020 553719 0.66381 .. PASS (literan/a HajdinjakNature2018 from MeyDirect: 95.4%; IntCal20, OxC39431‐38495 calBCE ‐38972 ‐39431 ‐38495 Neanderthal Late Middle Palaeolithic Spy_Neanderthal.SG Grotte de Spy, Jemeppe‐sur‐Sambre, Namur Belgium El Sidron 1253 FM865409.1 43.4 ‐5.33 ND1b1a* ND1b1a* https:/ROOT>NM>ND>ND1>ND1b>ND1b1>ND1b1a ND L YFull TMRCA ca. -

Exploring the Concept of Home at Hunter-Gatherer Sites in Upper Paleolithic Europe and Epipaleolithic Southwest Asia

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Previously Published Works Title Homes for hunters?: Exploring the concept of home at hunter-gatherer sites in upper paleolithic Europe and epipaleolithic Southwest Asia Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9nt6f73n Journal Current Anthropology, 60(1) ISSN 0011-3204 Authors Maher, LA Conkey, M Publication Date 2019-02-01 DOI 10.1086/701523 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Current Anthropology Volume 60, Number 1, February 2019 91 Homes for Hunters? Exploring the Concept of Home at Hunter-Gatherer Sites in Upper Paleolithic Europe and Epipaleolithic Southwest Asia by Lisa A. Maher and Margaret Conkey In both Southwest Asia and Europe, only a handful of known Upper Paleolithic and Epipaleolithic sites attest to aggregation or gatherings of hunter-gatherer groups, sometimes including evidence of hut structures and highly structured use of space. Interpretation of these structures ranges greatly, from mere ephemeral shelters to places “built” into a landscape with meanings beyond refuge from the elements. One might argue that this ambiguity stems from a largely functional interpretation of shelters that is embodied in the very terminology we use to describe them in comparison to the homes of later farming communities: mobile hunter-gatherers build and occupy huts that can form campsites, whereas sedentary farmers occupy houses or homes that form communities. Here we examine some of the evidence for Upper Paleolithic and Epipaleolithic structures in Europe and Southwest Asia, offering insights into their complex “functions” and examining perceptions of space among hunter-gatherer communities. We do this through examination of two contemporary, yet geographically and culturally distinct, examples: Upper Paleolithic (especially Magdalenian) evidence in Western Europe and the Epipaleolithic record (especially Early and Middle phases) in Southwest Asia. -

ARCL 0141 Mediterranean Prehistory

INSTITUTE OF ARCHAEOLOGY ARCL 0141 Mediterranean Prehistory 2019-20, Term 1 - 15 CREDITS Deadlines for coursework: 11th November 2019, 13th January 2020 Coordinator: Dr. Borja Legarra Herrero [email protected] Office 106, tel. (0) 20 7679 1539 Please see the last page of this document for important information about submission and marking procedures, or links to the relevant webpages 1 OVERVIEW Introduction This course reunites the study and analysis of prehistoric societies around the Mediterranean basin into a coherent if diverse exploration. It takes a long-term perspective, ranging from the first modern human occupation in the region to the start of the 1st millennium BCE, and a broad spatial approach, searching for the overall trends and conditions that underlie local phenomena. Opening topics include the glacial Mediterranean and origins of seafaring, early Holocene Levantine-European farming, and Chalcolithic societies. The main body of the course is formed by the multiple transformations of the late 4th, 3rd and 2nd millennium BC, including the environmental ‘mediterraneanisation’ of the basin, the rise of the first complex societies in east and west Mediterranean and the formation of world-system relations at the east Mediterranean. A final session examines the transition to the Iron Age in the context of the emergence of pan-Mediterranean networks, and this also acts as a link to G202. This course is designed to interlock with G206, which explores Mediterranean dynamics from a diachronic and comparative perspective. Equally, it can be taken in conjunction with courses in the prehistory of specific regions, such as the Aegean, Italy, the Levant, Anatolia and Egypt, as well as Europe and Africa. -

The Occurrence of Cereal Cultivation in China

The Occurrence of Cereal Cultivation in China TRACEY L-D LU NEARL Y EIGHTY YEARS HAVE ELAPSED since Swedish scholar J. G. Andersson discovered a piece of rice husk on a Yangshao potsherd found in the middle Yel low River Valley in 1927 (Andersson 1929). Today, many scholars agree that China 1 is one of the centers for an indigenous origin of agriculture, with broom corn and foxtail millets and rice being the major domesticated crops (e.g., Craw-· ford 2005; Diamond and Bellwood 2003; Higham 1995; Smith 1995) and dog and pig as the primary animal domesticates (Yuan 2001). It is not clear whether chicken and water buffalo were also indigenously domesticated in China (Liu 2004; Yuan 2001). The origin of agriculture in China by no later than 9000 years ago is an impor tant issue in prehistoric archaeology. Agriculture is the foundation of Chinese civ ilization. Further, the expansion of agriculture in Asia might have related to the origin and dispersal of the Austronesian and Austroasiatic speakers (e.g., Bellwood 2005; Diamond and Bellwood 2003; Glover and Higham 1995; Tsang 2005). Thus the issue is essential for our understanding of Asian and Pacific prehistory and the origins of agriculture in the world. Many scholars have discussed various aspects regarding the origin of agriculture in China, particularly after the 1960s (e.g., Bellwood 1996, 2005; Bellwood and Renfrew 2003; Chen 1991; Chinese Academy of Agronomy 1986; Crawford 1992, 2005; Crawford and Shen 1998; Flannery 1973; Higham 1995; Higham and Lu 1998; Ho 1969; Li and Lu 1981; Lu 1998, 1999, 2001, 2002; MacN eish et al. -

Stone Tools in the Paleolithic and Neolithic Near East: a Guide John J

Stone Tools in the Paleolithic and Neolithic Near East: A Guide John J. Shea New York: Cambridge University Press, 2013, 408 pp. (hardback), $104.99. ISBN-13: 978-1-107-00698-0. Reviewed by DEBORAH I. OLSZEWSKI Department of Anthropology, Penn Museum, 3260 South Street, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA 19104, USA; [email protected] n reading the Preface and Introduction to Shea’s book Stone Age Prehistory,” and lists the origins of genus Homo Iwhere he discusses why he wrote this volume on Near in the Lower Paleolithic period, which is incorrect both Eastern stone tools, I had to smile because his experience as temporally and geographically (Homo ergaster appearing ca a graduate student was analogous to mine. Learning about 1.8 Mya in Africa, or Homo habilis ca 2.5 Mya in Africa, if one stone tools in this world region was not easy because no accepts this hominin as sufficiently derived as to belong to single typology had been developed, at least in the sense genus Homo). And the same is true in this table for several of a widely accepted set of terminology that could be ap- other major evolutionary events for which our earliest evi- plied to the Paleolithic and Epipaleolithic there, or even the dence is African rather than Levantine. Neolithic period. In retrospect, it is somewhat surprising For Chapter 2 (Lithics Basics), the reader is immedi- that in the several decades since no one, until this book by ately immersed in how stone fractures (using terminol- Shea, undertook producing a compendium of information ogy from mechanics), is abraded, and is knapped. -

Human Origin Sites and the World Heritage Convention in Eurasia

World Heritage papers41 HEADWORLD HERITAGES 4 Human Origin Sites and the World Heritage Convention in Eurasia VOLUME I In support of UNESCO’s 70th Anniversary Celebrations United Nations [ Cultural Organization Human Origin Sites and the World Heritage Convention in Eurasia Nuria Sanz, Editor General Coordinator of HEADS Programme on Human Evolution HEADS 4 VOLUME I Published in 2015 by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, 7, place de Fontenoy, 75352 Paris 07 SP, France and the UNESCO Office in Mexico, Presidente Masaryk 526, Polanco, Miguel Hidalgo, 11550 Ciudad de Mexico, D.F., Mexico. © UNESCO 2015 ISBN 978-92-3-100107-9 This publication is available in Open Access under the Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO (CC-BY-SA 3.0 IGO) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/igo/). By using the content of this publication, the users accept to be bound by the terms of use of the UNESCO Open Access Repository (http://www.unesco.org/open-access/terms-use-ccbysa-en). The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNESCO concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The ideas and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors; they are not necessarily those of UNESCO and do not commit the Organization. Cover Photos: Top: Hohle Fels excavation. © Harry Vetter bottom (from left to right): Petroglyphs from Sikachi-Alyan rock art site.