Estonian: Typological Studies V

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Studies on Language Change. Working Papers in Linguistics No. 34

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 286 382 FL 016 932 AUTHOR Joseph, Brian D., Ed. TITLE Studies on Language Change. Working Papers in Linguistics No. 34. INSTITUTION Ohio State Univ., Columbus. Dept. of Linguistics. PUB DATE Dec 86 NOTE 171p. PUB TYPE Reports - Evaluative/Feasibility (142) -- Collected Works - General (020) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC07 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Arabic; Diachronic Linguistics; Dialects; *Diglossia; English; Estonian; *Etymology; Finnish; Foreign Countries; Language Variation; Linguistic Borrowing; *Linguistic Theory; *Morphemes; *Morphology (Languages); Old English; Sanskrit; Sociolinguistics; Syntax; *Uncommonly Taught Languages; Word Frequency IDENTIFIERS Saame ABSTRACT A collection of papers relevant to historical linguistics and description and explanation of language change includes: "Decliticization and Deaffixation in Saame: Abessive 'taga'" (Joel A. Nevis); "Decliticization in Old Estonian" (Joel A. Nevis); "On Automatic and Simultaneous Syntactic Changes" (Brian D. Joseph); "Loss of Nominal Case Endings in the Modern Arabic Sedentary Dialects" (Ann M. Miller); "One Rule or Many? Sanskrit Reduplication as Fragmented Affixation" (Richard D. Janda, Brian D. Joseph); "Fragmentation of Strong Verb Ablaut in Old English" (Keith Johnson); "The Etymology of 'bum': Mere Child's Play" (Mary E. Clark, Brian D. Joseph); "Small Group Lexical Innovation: Some Examples" (Christopher Kupec); "Word Frequency and Dialect Borrowing" (Debra A. Stollenwerk); "Introspection into a Stable Case of Variation in Finnish" (Riitta Valimaa-Blum); -

The Võro Language in Education in Estonia

THE VÕRO LANGUAGE IN EDUCATION IN ESTONIA European Research Centre on Multilingualism and Language Learning VÕRO The Võro language in education in Estonia c/o Fryske Akademy Doelestrjitte 8 P.O. Box 54 NL-8900 AB Ljouwert/Leeuwarden The Netherlands T 0031 (0) 58 - 234 3027 W www.mercator-research.eu E [email protected] | Regional dossiers series | t ca r cum n n i- ual e : Available in this series: This document was published by the Mercator European Research Centre on Asturian; the Asturian language in education in Spain Multilingualism and Language Learning with financial support from the FryskeAkademy Basque; the Basque language in education in France (2nd) and (until 2007) the European Commission (DG: Culture and Education) and (from 2007 Basque; the Basque language in education in Spain (2nd) onwards) the Province of Fryslân and the municipality of Leeuwarden. Breton; the Breton language in education in France (2nd) Catalan; the Catalan language in education in France Catalan; the Catalan language in education in Spain Cornish; the Cornish language in education in the UK © Mercator European Research Centre on Multilingualism and Language Corsican; the Corsican language in education in France Learning, 2007 Croatian; the Croatian language in education in Austria Frisian; the Frisian language in education in the Netherlands (4th) ISSN: 1570 – 1239 Gaelic; the Gaelic language in education in the UK Galician; the Galician language in education in Spain The cover of this dossier changed with the reprint of 2008. German; the German language in education in Alsace, France (2nd) German; the German language in education in Belgium The contents of this publication may be reproduced in print, except for commercial pur- German; the German language in education in South Tyrol, Italy poses, provided that the extract is preceded by a full reference to the Mercator European Hungarian; the Hungarian language in education in Slovakia Research Centre on Multilingualism and Language Learning. -

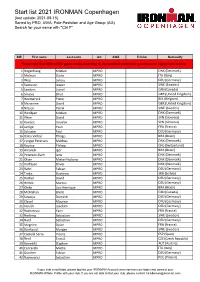

Start List 2021 IRONMAN Copenhagen (Last Update: 2021-08-15) Sorted by PRO, AWA, Pole Posistion and Age Group (AG) Search for Your Name with "Ctrl F"

Start list 2021 IRONMAN Copenhagen (last update: 2021-08-15) Sorted by PRO, AWA, Pole Posistion and Age Group (AG) Search for your name with "Ctrl F" BIB First name Last name AG AWA TriClub Nationallty Please note that BIBs will be given onsite according to the selected swim time you choose in registration oniste. 1 Hogenhaug Kristian MPRO DNK (Denmark) 2 Molinari Giulio MPRO ITA (Italy) 3 Wojt Lukasz MPRO DEU (Germany) 4 Svensson Jesper MPRO SWE (Sweden) 5 Sanders Lionel MPRO CAN (Canada) 6 Smales Elliot MPRO GBR (United Kingdom) 7 Heemeryck Pieter MPRO BEL (Belgium) 8 Mcnamee David MPRO GBR (United Kingdom) 9 Nilsson Patrik MPRO SWE (Sweden) 10 Hindkjær Kristian MPRO DNK (Denmark) 11 Plese David MPRO SVN (Slovenia) 12 Kovacic Jaroslav MPRO SVN (Slovenia) 14 Jarrige Yvan MPRO FRA (France) 15 Schuster Paul MPRO DEU (Germany) 16 Dário Vinhal Thiago MPRO BRA (Brazil) 17 Lyngsø Petersen Mathias MPRO DNK (Denmark) 18 Koutny Philipp MPRO CHE (Switzerland) 19 Amorelli Igor MPRO BRA (Brazil) 20 Petersen-Bach Jens MPRO DNK (Denmark) 21 Olsen Mikkel Hojborg MPRO DNK (Denmark) 22 Korfitsen Oliver MPRO DNK (Denmark) 23 Rahn Fabian MPRO DEU (Germany) 24 Trakic Strahinja MPRO SRB (Serbia) 25 Rother David MPRO DEU (Germany) 26 Herbst Marcus MPRO DEU (Germany) 27 Ohde Luis Henrique MPRO BRA (Brazil) 28 McMahon Brent MPRO CAN (Canada) 29 Sowieja Dominik MPRO DEU (Germany) 30 Clavel Maurice MPRO DEU (Germany) 31 Krauth Joachim MPRO DEU (Germany) 32 Rocheteau Yann MPRO FRA (France) 33 Norberg Sebastian MPRO SWE (Sweden) 34 Neef Sebastian MPRO DEU (Germany) 35 Magnien Dylan MPRO FRA (France) 36 Björkqvist Morgan MPRO SWE (Sweden) 37 Castellà Serra Vicenç MPRO ESP (Spain) 38 Řenč Tomáš MPRO CZE (Czech Republic) 39 Benedikt Stephen MPRO AUT (Austria) 40 Ceccarelli Mattia MPRO ITA (Italy) 41 Günther Fabian MPRO DEU (Germany) 42 Najmowicz Sebastian MPRO POL (Poland) If your club is not listed, please log into your IRONMAN Account (www.ironman.com/login) and connect your IRONMAN Athlete Profile with your club. -

Legacy Image

5-(948-~gblb SOWARE ENGINEERING LABORATORY SERIES SEL-95-004 PROCEEDINGS OF THE TWENTIETH ANNUAL SOFTWARE ENGINEERING WORKSHOP DECEMBER 1995 National Aeronautics and Space Administration Goddard Space Flight Center Greenbelt, Maryland 20771 Proceedings of the Twentieth Annual Software Engineering Workshop November 29-30,1995 GODDARD SPACE FLIGHT CENTER Greenbelt, Maryland The Software Engineering Laboratory (SEL) is an organization sponsored by the National Aeronautics and Space AdministratiodGoddard Space Flight Center (NASAIGSFC) and created to investigate the effectiveness of software engineering technologies when applied to the development of applications software. The SEL was created in 1976 and has three primary organizational members: NASAIGSFC, Software Engineering Branch The University of Maryland, Department of Computer Science .I Computer Sciences Corporation, Software Engineering Operation The goals of the SEL are (1) to understand the software development process in the GSFC environment; (2) to measure the effects of various methodologies, tools, and models on this process; and (3) to identifjr and then to apply successful development practices. The activities, findings, and recommendations of the SEL are recorded in the Software Engineering Laboratory Series, a continuing series of reports that includes this document. Documents from the Software Engineering Laboratory Series can be obtained via the SEL homepage at: or by writing to: Software Engineering Branch Code 552 Goddard Space Flight Center Greenbelt, Maryland 2077 1 SEW Proceedings iii The views and findings expressed herein are those of, the authors and presenters and do not necessarily represent the views, estimates, or policies of the SEL. All material herein is reprinted as submitted by authors and presenters, who are solely responsible for compliance with any relevant copyright, patent, or other proprietary restrictions. -

The Chronicle Henry of Livonia

THE CHRONICLE of HENRY OF LIVONIA HENRICUS LETTUS TRANSLATED WITH A NEW INTRODUCTION AND NOTES BY James A. Brundage � COLUMBIA UNIVERSI'IY PRESS NEW YORK Columbia University Press RECORDS OF WESTERN CIVILIZATION is a series published under the aus Publishers Since 1893 pices of the InterdepartmentalCommittee on Medieval and Renaissance New York Chichester,West Sussex Studies of the Columbia University Graduate School. The Western Records are, in fact, a new incarnation of a venerable series, the Co Copyright© University ofWisconsin Press, 1961 lumbia Records of Civilization, which, for more than half a century, New introduction,notes, and bibliography© 2003 Columbia University Press published sources and studies concerning great literary and historical All rights reserved landmarks. Many of the volumes of that series retain value, especially for their translations into English of primary sources, and the Medieval and Renaissance Studies Committee is pleased to cooperate with Co Library of Congress Cataloging-in-PublicationData lumbia University Press in reissuing a selection of those works in pa Henricus, de Lettis, ca. II 87-ca. 12 59. perback editions, especially suited for classroom use, and in limited [Origines Livoniae sacrae et civilis. English] clothbound editions. The chronicle of Henry of Livonia / Henricus Lettus ; translatedwith a new introduction and notes by James A. Brundage. Committee for the Records of Western Civilization p. cm. - (Records of Western civilization) Originally published: Madison : University of Wisconsin Press, 1961. Caroline Walker Bynum With new introd. Joan M. Ferrante Includes bibliographical references and index. CarmelaVircillo Franklin Robert Hanning ISBN 978-0-231-12888-9 (cloth: alk. paper)---ISBN 978-0-231-12889-6 (pbk.: alk. -

Journal of Language Relationship

Российский государственный гуманитарный университет Russian State University for the Humanities Russian State University for the Humanities Institute of Linguistics of the Russian Academy of Sciences Journal of Language Relationship International Scientific Periodical Nº 3 (16) Moscow 2018 Российский государственный гуманитарный университет Институт языкознания Российской Академии наук Вопросы языкового родства Международный научный журнал № 3 (16) Москва 2018 Advisory Board: H. EICHNER (Vienna) / Chairman W. BAXTER (Ann Arbor, Michigan) V. BLAŽEK (Brno) M. GELL-MANN (Santa Fe, New Mexico) L. HYMAN (Berkeley) F. KORTLANDT (Leiden) A. LUBOTSKY (Leiden) J. P. MALLORY (Belfast) A. YU. MILITAREV (Moscow) V. F. VYDRIN (Paris) Editorial Staff: V. A. DYBO (Editor-in-Chief) G. S. STAROSTIN (Managing Editor) T. A. MIKHAILOVA (Editorial Secretary) A. V. DYBO S. V. KULLANDA M. A. MOLINA M. N. SAENKO I. S. YAKUBOVICH Founded by Kirill BABAEV © Russian State University for the Humanities, 2018 Редакционный совет: Х. АЙХНЕР (Вена) / председатель В. БЛАЖЕК (Брно) У. БЭКСТЕР (Анн Арбор) В. Ф. ВЫДРИН (Париж) М. ГЕЛЛ-МАНН (Санта-Фе) Ф. КОРТЛАНДТ (Лейден) А. ЛУБОЦКИЙ (Лейден) Дж. МЭЛЛОРИ (Белфаст) А. Ю. МИЛИТАРЕВ (Москва) Л. ХАЙМАН (Беркли) Редакционная коллегия: В. А. ДЫБО (главный редактор) Г. С. СТАРОСТИН (заместитель главного редактора) Т. А. МИХАЙЛОВА (ответственный секретарь) А. В. ДЫБО С. В. КУЛЛАНДА М. А. МОЛИНА М. Н. САЕНКО И. С. ЯКУБОВИЧ Журнал основан К. В. БАБАЕВЫМ © Российский государственный гуманитарный университет, 2018 Вопросы языкового родства: Международный научный журнал / Рос. гос. гуманитар. ун-т; Рос. акад. наук. Ин-т языкознания; под ред. В. А. Дыбо. ― М., 2018. ― № 3 (16). ― x + 78 с. Journal of Language Relationship: International Scientific Periodical / Russian State Uni- versity for the Humanities; Russian Academy of Sciences. -

South Estonian Written Standard and Actual Spoken Language: Variation of the Past Participle Markers*

LINGUISTICA URALICA XLIII 2007 3 MARI METS (Tartu) SOUTH ESTONIAN WRITTEN STANDARD AND ACTUAL SPOKEN LANGUAGE: VARIATION OF THE PAST PARTICIPLE MARKERS* Abstract. The present article gives an overview of the past participle markers in spoken Võru; the variation of these markers exemplifies the (dis)similarities of the written standard and local spoken varieties. In regard to the active past participle -nuq/-nüq is standardised for the written norm, though today -nu/ -nü prevails in spoken language. For the passive past participle -t/-d is the singular marker and -tuq/-tüq/-duq/-düq marks the plural in the Võru written standard. Notwithstanding, the spoken variant suggests that nowadays there is no clear distinction between the singular and plural. Whereby, the present article aims to determine the validity of the historical number agreement in spoken language collected from the 1960s to the 1990s. The analysis is based on the texts (recorded between the 1960s and 1980s) available in the corpus of the Estonian dialects. The results are compared with the studies based on the 1990s recordings. The article demonstrates that the actual spoken language has lost some older South Estonian traits that have been standardised in the written variant. Keywords: Võru South Estonian, language variation, past participle markers, language history. 1. Introduction From the 16th to the early 20th century there were two literary languages in Estonia called the Tartu literary language (in South Estonia) and the Tallinn literary language (in North Estonia). During the second half of the 19th century the South Estonian literary language started a gradual decline because of the socio-political changes in the society, and the North Estonian literary language gained prominence. -

The Seto Language in Estonia

Working Papers in European Language Diversity 8 Kadri Koreinik The Seto language in Estonia: An Overview of a Language in Context Mainz Helsinki Wien Tartu Mariehamn Oulu Maribor Working Papers in European Language Diversity is a peer-reviewed online publication series of the research project ELDIA, serving as an outlet for preliminary research findings, individual case studies, background and spin-off research. Editor-in-Chief Johanna Laakso (Wien) Editorial Board Kari Djerf (Helsinki), Riho Grünthal (Helsinki), Anna Kolláth (Maribor), Helle Metslang (Tartu), Karl Pajusalu (Tartu), Anneli Sarhimaa (Mainz), Sia Spiliopoulou Åkermark (Mariehamn), Helena Sulkala (Oulu), Reetta Toivanen (Helsinki) Publisher Research consortium ELDIA c/o Prof. Dr. Anneli Sarhimaa Northern European and Baltic Languages and Cultures (SNEB) Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz Jakob-Welder-Weg 18 (Philosophicum) D-55099 Mainz, Germany Contact: [email protected] © European Language Diversity for All (ELDIA) ELDIA is an international research project funded by the European Commission. The views expressed in the Working Papers in European Language Diversity are the sole responsibility of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Commission. All contents of the Working Papers in European Language Diversity are subject to the Austrian copyright law. The contents may be used exclusively for private, non-commercial purposes. Regarding any further uses of the Working Papers in European Language Diversity, please contact the publisher. ISSN 2192-2403 Working Papers in European Language Diversity 8 During the initial stage of the research project ELDIA (European Language Diversity for All) in 2010, "structured context analyses" of each speaker community at issue were prepared. -

Carnegie Hall Rental

Friday Evening, October 26, 2012, at 8:00 Isaac Stern Auditorium/Ronald O. Perelman Stage Conductor’s Notes Q&A with Leon Botstein at 7:00 presents 50th Birthday Celebration LEON BOTSTEIN, Conductor JOHN STAFFORD SMITH The Star-Spangled Banner Arr. by LEOPOLD STOKOWSKI CHARLES IVES Symphony No. 4 Prelude: Maestoso Allegretto Fugue: Andante moderato Largo maestoso BLAIR MCMILLEN, Piano THE COLLEGIATE CHORALE Intermission GUSTAV MAHLER Symphony No. 8 in E-flat Major (“Symphony of a Thousand”) Part 1: Hymnus: Veni, Creator Spiritus Part 2: Final scene from Goethe’s Faust Part 2 Magna Peccatrix: REBECCA DAVIS, Soprano Una Poenitentium: ABBIE FURMANSKY, Soprano Mater Gloriosa: KATHERINE WHYTE, Soprano Mulier Samaritana: SUSAN PLATTS, Mezzo-soprano Maria Aegyptiaca: FREDRIKA BRILLEMBOURG, Mezzo-soprano (continued) This evening’s concerT will run approximaTely Two and a half hours, inlcuding one 20-minuTe inTermission. The Empire State Building is liT red and white this evening in honor of American Symphony Orchestra’s 50th Birthday. We would like to Thank the Empire State Building for This special honor. American Symphony Orchestra welcomes students and teachers from ASO’s arts education program, Music Notes. For information on how you can support Music Notes, visit AmericanSymphony.org. PLEASE SWITCH OFF YOUR CELL PHONES AND OTHER ELECTRONIC DEVICES. Dr. Marianus: CLAY HILLEY, Tenor Pater EcsTaticus: TYLER DUNCAN, Baritone Pater Profundus: DENIS SEDOV, Bass THE COLLEGIATE CHORALE JAMES BAGWELL, Director THE BROOKLYN YOUTH CHORUS DIANNE BERKUN, Director THE Program JOHN STAFFORD SMITH (Arr. by LEOPOLD STOKOWSKI) The Star-Spangled Banner Smith: Born March 30, 1750 in Gloucester, England Died September 21, 1836 in London Stokowski: Born April 18, 1882 in London Died September 13, 1977 in Nether Wallop, Hampshire, England Composed by Smith as “The Anacreontic Song” in 1775 in London Stokowski first arranged the song in 1940. -

The Berkeley Rep Magazine 2017–18 · Issues 5–6

aids in the United States today 25 · 4 questions for the cast 27 · The program for Angels in America: A Gay Fantasia on National Themes 33 THE BERKELEY REP MAGAZINE 2017–18 · ISSUES 5–6 AG_program.indd 1 4/4/18 3:54 PM Encore spread.indd 1 2/28/18 3:55 PM Encore spread.indd 1 2/28/18 3:55 PM AG_program.indd 4 4/4/18 3:54 PM IN THIS ISSUE 16 23 29 BERKELEY REP PRESENTS MEET THE CAST & CREW · 34 ANGELS IN AMERICA: A GAY FANTASIA ON NATIONAL THEMES · 33 PROLOGUE A letter from the artistic director · 7 Connect with us online! A letter from the managing director · 8 Visit our website berkeleyrep.org facebook.com/ @berkeleyrep You can buy tickets and plan your visit, berkeleyrep watch videos, sign up for classes, donate to vimeo.com/ @berkeleyrep REPORTS the Theatre, and explore Berkeley Rep. berkeleyrep The Messenger has arrived: berkeleyrep. berkeleyrep The art of theatrical flying ·13 We’re mobile! tumblr.com Crossing paths: Download our free iPhone or Google Play app —or visit our mobile site —to buy tickets, read An intergenerational conversation · 16 the buzz, watch videos, and plan your visit. June 2018, when 21 Ground Floor projects roam · 19 Considerations FEATURES Only beverages in cans, cartons, or cups with You are welcome to take a closer look, but The Origin Story · 20 lids are allowed in the house. Food is prohibited please don’t step onto the stage or touch in the house. the props. Tinkering and tinkering: An interview with Tony Kushner and Tony Taccone · 21 Smoking and the use of e-cigarettes is prohibited Any child who can quietly sit in their own by law on Berkeley Rep’s property. -

Applying the Principle of Simplicity to the Preparation of Effective English Materials for Students in Iranian High Schools

APPLYING THE PRINCIPLE OF SIMPLICITY TO THE PREPARATION OF EFFECTIVE ENGLISH MATERIALS FOR STUDENTS IN IRANIAN HIGH SCHOOLS By MOHAMMAD ALI FARNIA A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE COUNCIL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 1980 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank Professor Arthur J. Lewis, my advisor and chairperson of my dissertation committee, for his valuable guidance, not only in regard to this project, but during my past two years at the Uni- versity of Florida. I believe that without his help and extraordinary patience this project would never have been completed, I am also grateful to Professor Jayne C. Harder, my co-chairperson, for the invaluable guidance and assistance I received from her. I am greatly indebted to her for her keen and insightful comments, for her humane treatment, and, above all, for the confidence and motivation that she created in me in the course of writing this dissertation. I owe many thanks to the members of my doctoral committee. Pro- fessors Robert Wright, Vincent McGuire, and Eugene A. Todd, for their careful reading of this dissertation and constructive criticism. I would like to express my sincere gratitude and appreciation to my younger brother Aziz Farnia, whose financial support made my graduate studies in the United States possible. My personal appreciation goes to Miss Sofia Kohli ("Superfish") for typing the final version of this dissertation. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS , LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ^ ABSTRACT ^ii CHAPTER I I INTRODUCTION The Problem Statement 3 The Need for the Study 4 Problems of Iranian Students 7 Definition of Terms 11 Delimitations of the Study 17 Organization of the Dissertation 17 II REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE 19 Learning Theories 19 Innateness Universal s in Language and Language Learning .. -

Berkeley Linguistics Society

PROCEEDINGS OF THE FORTY-FIRST ANNUAL MEETING OF THE BERKELEY LINGUISTICS SOCIETY February 7-8, 2015 General Session Special Session Fieldwork Methodology Editors Anna E. Jurgensen Hannah Sande Spencer Lamoureux Kenny Baclawski Alison Zerbe Berkeley Linguistics Society Berkeley, CA, USA Berkeley Linguistics Society University of California, Berkeley Department of Linguistics 1203 Dwinelle Hall Berkeley, CA 94720-2650 USA All papers copyright c 2015 by the Berkeley Linguistics Society, Inc. All rights reserved. ISSN: 0363-2946 LCCN: 76-640143 Contents Acknowledgments . v Foreword . vii The No Blur Principle Effects as an Emergent Property of Language Systems Farrell Ackerman, Robert Malouf . 1 Intensification and sociolinguistic variation: a corpus study Andrea Beltrama . 15 Tagalog Sluicing Revisited Lena Borise . 31 Phonological Opacity in Pendau: a Local Constraint Conjunction Analysis Yan Chen . 49 Proximal Demonstratives in Predicate NPs Ryan B . Doran, Gregory Ward . 61 Syntax of generic null objects revisited Vera Dvořák . 71 Non-canonical Noun Incorporation in Bzhedug Adyghe Ksenia Ershova . 99 Perceptual distribution of merging phonemes Valerie Freeman . 121 Second Position and “Floating” Clitics in Wakhi Zuzanna Fuchs . 133 Some causative alternations in K’iche’, and a unified syntactic derivation John Gluckman . 155 The ‘Whole’ Story of Partitive Quantification Kristen A . Greer . 175 A Field Method to Describe Spontaneous Motion Events in Japanese Miyuki Ishibashi . 197 i On the Derivation of Relative Clauses in Teotitlán del Valle Zapotec Nick Kalivoda, Erik Zyman . 219 Gradability and Mimetic Verbs in Japanese: A Frame-Semantic Account Naoki Kiyama, Kimi Akita . 245 Exhaustivity, Predication and the Semantics of Movement Peter Klecha, Martina Martinović . 267 Reevaluating the Diphthong Mergers in Japono-Ryukyuan Tyler Lau .