50 Clinical Neurogenetics Brent L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Design of a Bioactive Small Molecule That Targets R(AUUCU) Repeats in Spinocerebellar Ataxia 10

ARTICLE Received 24 Jun 2015 | Accepted 18 Apr 2016 | Published 1 Jun 2016 DOI: 10.1038/ncomms11647 OPEN Design of a bioactive small molecule that targets r(AUUCU) repeats in spinocerebellar ataxia 10 Wang-Yong Yang1, Rui Gao2, Mark Southern3, Partha S. Sarkar2 & Matthew D. Disney1 RNA is an important target for chemical probes of function and lead therapeutics; however, it is difficult to target with small molecules. One approach to tackle this problem is to identify compounds that target RNA structures and utilize them to multivalently target RNA. Here we show that small molecules can be identified to selectively bind RNA base pairs by probing a library of RNA-focused small molecules. A small molecule that selectively binds AU base pairs informed design of a dimeric compound (2AU-2) that targets the pathogenic RNA, expanded r(AUUCU) repeats, that causes spinocerebellar ataxia type 10 (SCA10) in patient- derived cells. Indeed, 2AU-2 (50 nM) ameliorates various aspects of SCA10 pathology including improvement of mitochondrial dysfunction, reduced activation of caspase 3, and reduction of nuclear foci. These studies provide a first-in-class chemical probe to study SCA10 RNA toxicity and potentially define broadly applicable compounds targeting RNA AU base pairs in cells. 1 Departments of Chemistry and Neuroscience, The Scripps Research Institute, Scripps Florida, Jupiter, Florida 33458, USA. 2 Mitchell Center for Neurodegenerative Disorders, Department of Neurology, Neuroscience and Cell Biology, University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, Texas 77555, USA. 3 Informatics Core, The Scripps Research Institute, Scripps Florida, Jupiter, Florida 33458, USA. Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to M.D.D. -

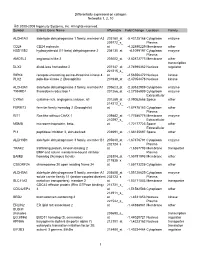

Differentially Expressed on Collagen Networks 1, 2, 10 © 2000-2009 Ingenuity Systems, Inc. All Rights Reserved. Symbol Entrez

Differentially expressed on collagen Networks 1, 2, 10 © 2000-2009 Ingenuity Systems, Inc. All rights reserved. Symbol Entrez Gene Name Affymetrix Fold Change Location Family ALDH1A3 aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 family, member A3 203180_at -5.43125168 Cytoplasm enzyme 209772_s_ Plasma CD24 CD24 molecule at -4.32890229 Membrane other HSD11B2 hydroxysteroid (11-beta) dehydrogenase 2 204130_at -4.1099197 Cytoplasm enzyme Plasma AMOTL2 angiomotin like 2 203002_at -2.82872773 Membrane other transcription DLX2 distal-less homeobox 2 207147_at -2.74996362 Nucleus regulator 221215_s_ RIPK4 receptor-interacting serine-threonine kinase 4 at -2.56556472 Nucleus kinase PLK2 polo-like kinase 2 (Drosophila) 201939_at -2.47054478 Nucleus kinase ALDH3A1 aldehyde dehydrogenase 3 family, memberA1 205623_at -2.30532989 Cytoplasm enzyme TXNRD1 thioredoxin reductase 1 201266_at -2.27936909 Cytoplasm enzyme Extracellular CYR61 cysteine-rich, angiogenic inducer, 61 201289_at -2.09052668 Space other 214212_x_ FERMT2 fermitin family homolog 2 (Drosophila) at -1.87478183 Cytoplasm other Plasma RIT1 Ras-like without CAAX 1 209882_at -1.77586775 Membrane enzyme 210297_s_ Extracellular MSMB microseminoprotein, beta- at -1.72177723 Space other Extracellular PI3 peptidase inhibitor 3, skin-derived 203691_at -1.68135697 Space other ALDH3B1 aldehyde dehydrogenase 3 family, member B1 205640_at -1.67376791 Cytoplasm enzyme 202124_s_ Plasma TRAK2 trafficking protein, kinesin binding 2 at -1.6367793 Membrane transporter BMP and activin membrane-bound inhibitor Plasma BAMBI -

Supplemental Information

Supplemental information Dissection of the genomic structure of the miR-183/96/182 gene. Previously, we showed that the miR-183/96/182 cluster is an intergenic miRNA cluster, located in a ~60-kb interval between the genes encoding nuclear respiratory factor-1 (Nrf1) and ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2H (Ube2h) on mouse chr6qA3.3 (1). To start to uncover the genomic structure of the miR- 183/96/182 gene, we first studied genomic features around miR-183/96/182 in the UCSC genome browser (http://genome.UCSC.edu/), and identified two CpG islands 3.4-6.5 kb 5’ of pre-miR-183, the most 5’ miRNA of the cluster (Fig. 1A; Fig. S1 and Seq. S1). A cDNA clone, AK044220, located at 3.2-4.6 kb 5’ to pre-miR-183, encompasses the second CpG island (Fig. 1A; Fig. S1). We hypothesized that this cDNA clone was derived from 5’ exon(s) of the primary transcript of the miR-183/96/182 gene, as CpG islands are often associated with promoters (2). Supporting this hypothesis, multiple expressed sequences detected by gene-trap clones, including clone D016D06 (3, 4), were co-localized with the cDNA clone AK044220 (Fig. 1A; Fig. S1). Clone D016D06, deposited by the German GeneTrap Consortium (GGTC) (http://tikus.gsf.de) (3, 4), was derived from insertion of a retroviral construct, rFlpROSAβgeo in 129S2 ES cells (Fig. 1A and C). The rFlpROSAβgeo construct carries a promoterless reporter gene, the β−geo cassette - an in-frame fusion of the β-galactosidase and neomycin resistance (Neor) gene (5), with a splicing acceptor (SA) immediately upstream, and a polyA signal downstream of the β−geo cassette (Fig. -

Autosomal Dominant Cerebellar Ataxia Type I: a Review of the Phenotypic and Genotypic Characteristics

Whaley et al. Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases 2011, 6:33 http://www.ojrd.com/content/6/1/33 REVIEW Open Access Autosomal dominant cerebellar ataxia type I: A review of the phenotypic and genotypic characteristics Nathaniel Robb Whaley1,2, Shinsuke Fujioka2 and Zbigniew K Wszolek2* Abstract Type I autosomal dominant cerebellar ataxia (ADCA) is a type of spinocerebellar ataxia (SCA) characterized by ataxia with other neurological signs, including oculomotor disturbances, cognitive deficits, pyramidal and extrapyramidal dysfunction, bulbar, spinal and peripheral nervous system involvement. The global prevalence of this disease is not known. The most common type I ADCA is SCA3 followed by SCA2, SCA1, and SCA8, in descending order. Founder effects no doubt contribute to the variable prevalence between populations. Onset is usually in adulthood but cases of presentation in childhood have been reported. Clinical features vary depending on the SCA subtype but by definition include ataxia associated with other neurological manifestations. The clinical spectrum ranges from pure cerebellar signs to constellations including spinal cord and peripheral nerve disease, cognitive impairment, cerebellar or supranuclear ophthalmologic signs, psychiatric problems, and seizures. Cerebellar ataxia can affect virtually any body part causing movement abnormalities. Gait, truncal, and limb ataxia are often the most obvious cerebellar findings though nystagmus, saccadic abnormalities, and dysarthria are usually associated. To date, 21 subtypes have been identified: SCA1-SCA4, SCA8, SCA10, SCA12-SCA14, SCA15/16, SCA17-SCA23, SCA25, SCA27, SCA28 and dentatorubral pallidoluysian atrophy (DRPLA). Type I ADCA can be further divided based on the proposed pathogenetic mechanism into 3 subclasses: subclass 1 includes type I ADCA caused by CAG repeat expansions such as SCA1-SCA3, SCA17, and DRPLA, subclass 2 includes trinucleotide repeat expansions that fall outside of the protein-coding regions of the disease gene including SCA8, SCA10 and SCA12. -

Downloaded from Dbgap (Phs000607.V1)

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/751933; this version posted September 6, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. 1 Genetics and Pathway Analysis of Normative Cognitive Variation 2 in the Philadelphia Neurodevelopmental Cohort 3 4 Authors: 5 Shraddha Pai1, Shirley Hui1, Philipp Weber2, Owen Whitley1,3, Peipei Li4,5, Viviane Labrie4,5, Jan 6 Baumbach2,6, Gary D Bader1,3,7,8 7 8 Affiliations: 9 1. The Donnelly Centre, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada 10 2. Department of Mathematics and Computer Science, University of Southern Denmark, Odense, 11 Denmark 12 3. Department of Molecular Genetics, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada 13 4. Center for Neurodegenerative Science, Van Andel Research Institute, Grand Rapids, MI, USA 14 5. Division of Psychiatry and Behavioral Medicine, College of Human Medicine, Michigan State 15 University, Grand Rapids, MI, USA 16 6. TUM School of Life Sciences Weihenstephan, Technical University of Munich, Munich, Germany. 17 7. Department of Computer Science, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada 18 8. The Lunenfeld-Tanenbaum Research Institute, Mount Sinai Hospital, Toronto, Canada 19 20 21 22 * [email protected] 23 24 Page 1 of 23 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/751933; this version posted September 6, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. -

A Master Autoantigen-Ome Links Alternative Splicing, Female Predilection, and COVID-19 to Autoimmune Diseases

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.07.30.454526; this version posted August 4, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. A Master Autoantigen-ome Links Alternative Splicing, Female Predilection, and COVID-19 to Autoimmune Diseases Julia Y. Wang1*, Michael W. Roehrl1, Victor B. Roehrl1, and Michael H. Roehrl2* 1 Curandis, New York, USA 2 Department of Pathology, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, USA * Correspondence: [email protected] or [email protected] 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.07.30.454526; this version posted August 4, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. Abstract Chronic and debilitating autoimmune sequelae pose a grave concern for the post-COVID-19 pandemic era. Based on our discovery that the glycosaminoglycan dermatan sulfate (DS) displays peculiar affinity to apoptotic cells and autoantigens (autoAgs) and that DS-autoAg complexes cooperatively stimulate autoreactive B1 cell responses, we compiled a database of 751 candidate autoAgs from six human cell types. At least 657 of these have been found to be affected by SARS-CoV-2 infection based on currently available multi-omic COVID data, and at least 400 are confirmed targets of autoantibodies in a wide array of autoimmune diseases and cancer. -

Molecular Evidence for Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Bipolar Disorder

ORIGINAL ARTICLE Molecular Evidence for Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Bipolar Disorder Christine Konradi, PhD; Molly Eaton, BA; Matthew L. MacDonald, BS; John Walsh, MS; Francine M. Benes, MD, PhD; Stephan Heckers, MD Background: The disease mechanism of bipolar disor- Results: The expression of nuclear messenger RNA cod- der remains unknown. Recent studies have provided evi- ing for mitochondrial proteins was significantly de- dence for abnormal gene expression in bipolar disorder. creased in the hippocampus in subjects with bipolar dis- order but not in those with schizophrenia. Subjects with Objective: To determine the expression of 12558 nuclear bipolar disorder were characterized by a pronounced and genes in the human hippocampus in healthy control sub- extensive decrease in the expression of genes regulating jects and those with bipolar disorder or schizophrenia. oxidative phosphorylation and the adenosine triphos- phate–dependent process of proteasome degradation. Design: We used gene arrays to study messenger RNA expression. Data were verified with a real-time quanti- Conclusions: These findings point toward a wide- tative polymerase chain reaction assay. spread dysregulation of mitochondrial energy metabo- lism and downstream deficits of adenosine triphosphate– Subjects: We studied 10 healthy control subjects, 9 dependent processes in bipolar disorder. subjects with bipolar disorder, and 8 subjects with schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:300-308 IPOLAR DISORDER AFFECTS chondrial genes coding for mitochon- approximately 0.5% of the drial proteins.8 In this article, we report world population, often that the expression of nuclear messenger leading to recurrent illness RNA (mRNA) coding for mitochondrial and a marked decline in so- proteins is significantly decreased in the Bcial function.1 The clinical features of bi- hippocampus in bipolar disorder but not polar disorder (ie, recurrent episodes of de- in schizophrenia. -

Genetic Variation and Functional Analysis of the Cardiomedin Gene

TECHNISCHE UNIVERSITÄT MÜNCHEN LEHRSTUHL FÜR EXPERIMENTELLE GENETIK Genetic Variation and Functional Analysis of the Cardiomedin Gene Zasie Susanne Schäfer Vollständiger Abdruck der von der Fakultät Wissenschaftszentrum Weihenstephan für Ernährung, Landnutzung und Umwelt der Technischen Universität München zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades eines Doktors der Naturwissenschaften genehmigten Dissertation. Vorsitzende: Univ.-Prof. A. Schnieke, Ph.D. Prüfer der Dissertation: 1. apl. Prof. Dr. J. Adamski 2. Univ.-Prof. Dr. Dr. H.-R. Fries 3. Univ.-Prof. Dr. Th. Meitinger Die Dissertation wurde am. 31.05.2011 bei der Technischen Universität München eingereicht und durch die Fakultät Wissenschaftszentrum Weihenstephan für Ernährung, Landnutzung und Umwelt am 02.04.2012 angenommen. Table of Contents Table of contents Abbreviations ........................................................................................................................ 7 1. Summary ..........................................................................................................................10 Zusammenfassung ...............................................................................................................11 2. Introduction ......................................................................................................................12 2.1 Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) and post-GWAS functional genomics ......12 2.2 Genetic influences on cardiac repolarization and sudden cardiac death syndrome in GWAS and the chromosome -

Sheet1 Page 1 Gene Symbol Gene Description Entrez Gene ID

Sheet1 RefSeq ID ProbeSets Gene Symbol Gene Description Entrez Gene ID Sequence annotation Seed matches location(s) Ago-2 binding specific enrichment (replicate 1) Ago-2 binding specific enrichment (replicate 2) OE lysate log2 fold change (replicate 1) OE lysate log2 fold change (replicate 2) Probability NM_022823 218843_at FNDC4 Homo sapiens fibronectin type III domain containing 4 (FNDC4), mRNA. 64838 TR(1..1649)CDS(367..1071) 1523..1530 3.73 1.77 -1.91 -0.39 1 NM_003919 204688_at SGCE Homo sapiens sarcoglycan, epsilon (SGCE), transcript variant 2, mRNA. 8910 TR(1..1709)CDS(112..1425) 1495..1501 3.09 1.56 -1.02 -0.27 1 NM_006982 206837_at ALX1 Homo sapiens ALX homeobox 1 (ALX1), mRNA. 8092 TR(1..1320)CDS(5..985) 916..923 2.99 1.93 -0.19 -0.33 1 NM_019024 233642_s_at HEATR5B Homo sapiens HEAT repeat containing 5B (HEATR5B), mRNA. 54497 TR(1..6792)CDS(97..6312) 5827..5834,4309..4315 3.28 1.51 -0.92 -0.23 1 NM_018366 223431_at CNO Homo sapiens cappuccino homolog (mouse) (CNO), mRNA. 55330 TR(1..1546)CDS(96..749) 1062..1069,925..932 2.89 1.51 -1.2 -0.41 1 NM_032436 226194_at C13orf8 Homo sapiens chromosome 13 open reading frame 8 (C13orf8), mRNA. 283489 TR(1..3782)CDS(283..2721) 1756..1762,3587..3594,1725..1731,3395..3402 2.75 1.72 -1.38 -0.34 1 NM_031450 221534_at C11orf68 Homo sapiens chromosome 11 open reading frame 68 (C11orf68), mRNA. 83638 TR(1..1568)CDS(153..908) 967..973 3.07 1.35 -0.72 -0.06 1 NM_033318 225795_at,225794_s_at C22orf32 Homo sapiens chromosome 22 open reading frame 32 (C22orf32), mRNA. -

An Autoantigen-Ome from HS-Sultan B-Lymphoblasts Offers a Molecular Map for Investigating Autoimmune Sequelae of COVID-19

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.04.05.438500; this version posted April 6, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. An Autoantigen-ome from HS-Sultan B-Lymphoblasts Offers a Molecular Map for Investigating Autoimmune Sequelae of COVID-19 Julia Y. Wang1*, Wei Zhang2, Victor B. Roehrl1, Michael W. Roehrl1, and Michael H. Roehrl3,4* 1Curandis, New York, USA 2Department of Gastroenterology, Affiliated Hospital of Guizhou Medical University, Guizhou, China 3Department of Pathology and 4Human Oncology and Pathogenesis Program, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, USA *Correspondence: [email protected], [email protected] Keywords: Autoantigens, autoantibodies, autoimmunity, SARS-CoV-2, COVID, Epstein-Barr virus 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.04.05.438500; this version posted April 6, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. Abstract To understand how COVID-19 may induce autoimmune diseases, we have been compiling an atlas of COVID-autoantigens (autoAgs). Using dermatan sulfate (DS) affinity enrichment of autoantigenic proteins extracted from HS-Sultan lymphoblasts, we identified 362 DS-affinity proteins, of which at least 201 (56%) are confirmed autoAgs. Comparison with available multi-omic COVID data shows that 315 (87%) of the 362 proteins are affected in SARS-CoV-2 infection via altered expression, interaction with viral components, or modification by phosphorylation or ubiquitination, at least 186 (59%) of which are known autoAgs. -

Intrinsic Disorder in Proteins with Pathogenic Repeat Expansions

molecules Review Intrinsic Disorder in Proteins with Pathogenic Repeat Expansions April L. Darling 1,2,* ID and Vladimir N. Uversky 1,3,* ID 1 Department of Molecular Medicine, College of Medicine, Byrd Alzheimer’s Institute, University of South Florida, Tampa, FL 33612, USA 2 James A. Haley Veteran’s Hospital, Tampa, FL 33612, USA 3 Institute for Biological Instrumentation of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Pushchino, Moscow Region 142290, Russia * Correspondence: [email protected] (A.L.D.); [email protected] (V.N.U.); Tel.: +1-813-396-9249 (A.L.D.); +1-813-974-5816 (V.N.U.) Received: 8 November 2017; Accepted: 21 November 2017; Published: 24 November 2017 Abstract: Intrinsically disordered proteins and proteins with intrinsically disordered regions have been shown to be highly prevalent in disease. Furthermore, disease-causing expansions of the regions containing tandem amino acid repeats often push repetitive proteins towards formation of irreversible aggregates. In fact, in disease-relevant proteins, the increased repeat length often positively correlates with the increased aggregation efficiency and the increased disease severity and penetrance, being negatively correlated with the age of disease onset. The major categories of repeat extensions involved in disease include poly-glutamine and poly-alanine homorepeats, which are often times located in the intrinsically disordered regions, as well as repeats in non-coding regions of genes typically encoding proteins with ordered structures. Repeats in such non-coding regions of genes can be expressed at the mRNA level. Although they can affect the expression levels of encoded proteins, they are not translated as parts of an affected protein and have no effect on its structure. -

A Master Autoantigen-Ome Links Alternative Splicing, Female Predilection, and COVID-19 to Autoimmune Diseases

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.07.30.454526; this version posted August 4, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. A Master Autoantigen-ome Links Alternative Splicing, Female Predilection, and COVID-19 to Autoimmune Diseases Julia Y. Wang1*, Michael W. Roehrl1, Victor B. Roehrl1, and Michael H. Roehrl2* 1 Curandis, New York, USA 2 Department of Pathology, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, USA * Correspondence: [email protected] or [email protected] 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.07.30.454526; this version posted August 4, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. Abstract Chronic and debilitating autoimmune sequelae pose a grave concern for the post-COVID-19 pandemic era. Based on our discovery that the glycosaminoglycan dermatan sulfate (DS) displays peculiar affinity to apoptotic cells and autoantigens (autoAgs) and that DS-autoAg complexes cooperatively stimulate autoreactive B1 cell responses, we compiled a database of 751 candidate autoAgs from six human cell types. At least 657 of these have been found to be affected by SARS-CoV-2 infection based on currently available multi-omic COVID data, and at least 400 are confirmed targets of autoantibodies in a wide array of autoimmune diseases and cancer.