A Transcriptional Signature of Postmitotic Maintenance in Neural Tissues

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Design of a Bioactive Small Molecule That Targets R(AUUCU) Repeats in Spinocerebellar Ataxia 10

ARTICLE Received 24 Jun 2015 | Accepted 18 Apr 2016 | Published 1 Jun 2016 DOI: 10.1038/ncomms11647 OPEN Design of a bioactive small molecule that targets r(AUUCU) repeats in spinocerebellar ataxia 10 Wang-Yong Yang1, Rui Gao2, Mark Southern3, Partha S. Sarkar2 & Matthew D. Disney1 RNA is an important target for chemical probes of function and lead therapeutics; however, it is difficult to target with small molecules. One approach to tackle this problem is to identify compounds that target RNA structures and utilize them to multivalently target RNA. Here we show that small molecules can be identified to selectively bind RNA base pairs by probing a library of RNA-focused small molecules. A small molecule that selectively binds AU base pairs informed design of a dimeric compound (2AU-2) that targets the pathogenic RNA, expanded r(AUUCU) repeats, that causes spinocerebellar ataxia type 10 (SCA10) in patient- derived cells. Indeed, 2AU-2 (50 nM) ameliorates various aspects of SCA10 pathology including improvement of mitochondrial dysfunction, reduced activation of caspase 3, and reduction of nuclear foci. These studies provide a first-in-class chemical probe to study SCA10 RNA toxicity and potentially define broadly applicable compounds targeting RNA AU base pairs in cells. 1 Departments of Chemistry and Neuroscience, The Scripps Research Institute, Scripps Florida, Jupiter, Florida 33458, USA. 2 Mitchell Center for Neurodegenerative Disorders, Department of Neurology, Neuroscience and Cell Biology, University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, Texas 77555, USA. 3 Informatics Core, The Scripps Research Institute, Scripps Florida, Jupiter, Florida 33458, USA. Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to M.D.D. -

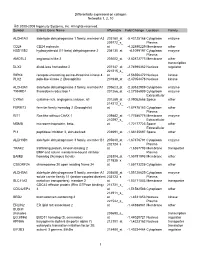

Differentially Expressed on Collagen Networks 1, 2, 10 © 2000-2009 Ingenuity Systems, Inc. All Rights Reserved. Symbol Entrez

Differentially expressed on collagen Networks 1, 2, 10 © 2000-2009 Ingenuity Systems, Inc. All rights reserved. Symbol Entrez Gene Name Affymetrix Fold Change Location Family ALDH1A3 aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 family, member A3 203180_at -5.43125168 Cytoplasm enzyme 209772_s_ Plasma CD24 CD24 molecule at -4.32890229 Membrane other HSD11B2 hydroxysteroid (11-beta) dehydrogenase 2 204130_at -4.1099197 Cytoplasm enzyme Plasma AMOTL2 angiomotin like 2 203002_at -2.82872773 Membrane other transcription DLX2 distal-less homeobox 2 207147_at -2.74996362 Nucleus regulator 221215_s_ RIPK4 receptor-interacting serine-threonine kinase 4 at -2.56556472 Nucleus kinase PLK2 polo-like kinase 2 (Drosophila) 201939_at -2.47054478 Nucleus kinase ALDH3A1 aldehyde dehydrogenase 3 family, memberA1 205623_at -2.30532989 Cytoplasm enzyme TXNRD1 thioredoxin reductase 1 201266_at -2.27936909 Cytoplasm enzyme Extracellular CYR61 cysteine-rich, angiogenic inducer, 61 201289_at -2.09052668 Space other 214212_x_ FERMT2 fermitin family homolog 2 (Drosophila) at -1.87478183 Cytoplasm other Plasma RIT1 Ras-like without CAAX 1 209882_at -1.77586775 Membrane enzyme 210297_s_ Extracellular MSMB microseminoprotein, beta- at -1.72177723 Space other Extracellular PI3 peptidase inhibitor 3, skin-derived 203691_at -1.68135697 Space other ALDH3B1 aldehyde dehydrogenase 3 family, member B1 205640_at -1.67376791 Cytoplasm enzyme 202124_s_ Plasma TRAK2 trafficking protein, kinesin binding 2 at -1.6367793 Membrane transporter BMP and activin membrane-bound inhibitor Plasma BAMBI -

Supplemental Information

Supplemental information Dissection of the genomic structure of the miR-183/96/182 gene. Previously, we showed that the miR-183/96/182 cluster is an intergenic miRNA cluster, located in a ~60-kb interval between the genes encoding nuclear respiratory factor-1 (Nrf1) and ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2H (Ube2h) on mouse chr6qA3.3 (1). To start to uncover the genomic structure of the miR- 183/96/182 gene, we first studied genomic features around miR-183/96/182 in the UCSC genome browser (http://genome.UCSC.edu/), and identified two CpG islands 3.4-6.5 kb 5’ of pre-miR-183, the most 5’ miRNA of the cluster (Fig. 1A; Fig. S1 and Seq. S1). A cDNA clone, AK044220, located at 3.2-4.6 kb 5’ to pre-miR-183, encompasses the second CpG island (Fig. 1A; Fig. S1). We hypothesized that this cDNA clone was derived from 5’ exon(s) of the primary transcript of the miR-183/96/182 gene, as CpG islands are often associated with promoters (2). Supporting this hypothesis, multiple expressed sequences detected by gene-trap clones, including clone D016D06 (3, 4), were co-localized with the cDNA clone AK044220 (Fig. 1A; Fig. S1). Clone D016D06, deposited by the German GeneTrap Consortium (GGTC) (http://tikus.gsf.de) (3, 4), was derived from insertion of a retroviral construct, rFlpROSAβgeo in 129S2 ES cells (Fig. 1A and C). The rFlpROSAβgeo construct carries a promoterless reporter gene, the β−geo cassette - an in-frame fusion of the β-galactosidase and neomycin resistance (Neor) gene (5), with a splicing acceptor (SA) immediately upstream, and a polyA signal downstream of the β−geo cassette (Fig. -

Supplementary Table S4. FGA Co-Expressed Gene List in LUAD

Supplementary Table S4. FGA co-expressed gene list in LUAD tumors Symbol R Locus Description FGG 0.919 4q28 fibrinogen gamma chain FGL1 0.635 8p22 fibrinogen-like 1 SLC7A2 0.536 8p22 solute carrier family 7 (cationic amino acid transporter, y+ system), member 2 DUSP4 0.521 8p12-p11 dual specificity phosphatase 4 HAL 0.51 12q22-q24.1histidine ammonia-lyase PDE4D 0.499 5q12 phosphodiesterase 4D, cAMP-specific FURIN 0.497 15q26.1 furin (paired basic amino acid cleaving enzyme) CPS1 0.49 2q35 carbamoyl-phosphate synthase 1, mitochondrial TESC 0.478 12q24.22 tescalcin INHA 0.465 2q35 inhibin, alpha S100P 0.461 4p16 S100 calcium binding protein P VPS37A 0.447 8p22 vacuolar protein sorting 37 homolog A (S. cerevisiae) SLC16A14 0.447 2q36.3 solute carrier family 16, member 14 PPARGC1A 0.443 4p15.1 peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma, coactivator 1 alpha SIK1 0.435 21q22.3 salt-inducible kinase 1 IRS2 0.434 13q34 insulin receptor substrate 2 RND1 0.433 12q12 Rho family GTPase 1 HGD 0.433 3q13.33 homogentisate 1,2-dioxygenase PTP4A1 0.432 6q12 protein tyrosine phosphatase type IVA, member 1 C8orf4 0.428 8p11.2 chromosome 8 open reading frame 4 DDC 0.427 7p12.2 dopa decarboxylase (aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase) TACC2 0.427 10q26 transforming, acidic coiled-coil containing protein 2 MUC13 0.422 3q21.2 mucin 13, cell surface associated C5 0.412 9q33-q34 complement component 5 NR4A2 0.412 2q22-q23 nuclear receptor subfamily 4, group A, member 2 EYS 0.411 6q12 eyes shut homolog (Drosophila) GPX2 0.406 14q24.1 glutathione peroxidase -

Autosomal Dominant Cerebellar Ataxia Type I: a Review of the Phenotypic and Genotypic Characteristics

Whaley et al. Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases 2011, 6:33 http://www.ojrd.com/content/6/1/33 REVIEW Open Access Autosomal dominant cerebellar ataxia type I: A review of the phenotypic and genotypic characteristics Nathaniel Robb Whaley1,2, Shinsuke Fujioka2 and Zbigniew K Wszolek2* Abstract Type I autosomal dominant cerebellar ataxia (ADCA) is a type of spinocerebellar ataxia (SCA) characterized by ataxia with other neurological signs, including oculomotor disturbances, cognitive deficits, pyramidal and extrapyramidal dysfunction, bulbar, spinal and peripheral nervous system involvement. The global prevalence of this disease is not known. The most common type I ADCA is SCA3 followed by SCA2, SCA1, and SCA8, in descending order. Founder effects no doubt contribute to the variable prevalence between populations. Onset is usually in adulthood but cases of presentation in childhood have been reported. Clinical features vary depending on the SCA subtype but by definition include ataxia associated with other neurological manifestations. The clinical spectrum ranges from pure cerebellar signs to constellations including spinal cord and peripheral nerve disease, cognitive impairment, cerebellar or supranuclear ophthalmologic signs, psychiatric problems, and seizures. Cerebellar ataxia can affect virtually any body part causing movement abnormalities. Gait, truncal, and limb ataxia are often the most obvious cerebellar findings though nystagmus, saccadic abnormalities, and dysarthria are usually associated. To date, 21 subtypes have been identified: SCA1-SCA4, SCA8, SCA10, SCA12-SCA14, SCA15/16, SCA17-SCA23, SCA25, SCA27, SCA28 and dentatorubral pallidoluysian atrophy (DRPLA). Type I ADCA can be further divided based on the proposed pathogenetic mechanism into 3 subclasses: subclass 1 includes type I ADCA caused by CAG repeat expansions such as SCA1-SCA3, SCA17, and DRPLA, subclass 2 includes trinucleotide repeat expansions that fall outside of the protein-coding regions of the disease gene including SCA8, SCA10 and SCA12. -

Downloaded from Dbgap (Phs000607.V1)

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/751933; this version posted September 6, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. 1 Genetics and Pathway Analysis of Normative Cognitive Variation 2 in the Philadelphia Neurodevelopmental Cohort 3 4 Authors: 5 Shraddha Pai1, Shirley Hui1, Philipp Weber2, Owen Whitley1,3, Peipei Li4,5, Viviane Labrie4,5, Jan 6 Baumbach2,6, Gary D Bader1,3,7,8 7 8 Affiliations: 9 1. The Donnelly Centre, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada 10 2. Department of Mathematics and Computer Science, University of Southern Denmark, Odense, 11 Denmark 12 3. Department of Molecular Genetics, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada 13 4. Center for Neurodegenerative Science, Van Andel Research Institute, Grand Rapids, MI, USA 14 5. Division of Psychiatry and Behavioral Medicine, College of Human Medicine, Michigan State 15 University, Grand Rapids, MI, USA 16 6. TUM School of Life Sciences Weihenstephan, Technical University of Munich, Munich, Germany. 17 7. Department of Computer Science, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada 18 8. The Lunenfeld-Tanenbaum Research Institute, Mount Sinai Hospital, Toronto, Canada 19 20 21 22 * [email protected] 23 24 Page 1 of 23 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/751933; this version posted September 6, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. -

A Master Autoantigen-Ome Links Alternative Splicing, Female Predilection, and COVID-19 to Autoimmune Diseases

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.07.30.454526; this version posted August 4, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. A Master Autoantigen-ome Links Alternative Splicing, Female Predilection, and COVID-19 to Autoimmune Diseases Julia Y. Wang1*, Michael W. Roehrl1, Victor B. Roehrl1, and Michael H. Roehrl2* 1 Curandis, New York, USA 2 Department of Pathology, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, USA * Correspondence: [email protected] or [email protected] 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.07.30.454526; this version posted August 4, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. Abstract Chronic and debilitating autoimmune sequelae pose a grave concern for the post-COVID-19 pandemic era. Based on our discovery that the glycosaminoglycan dermatan sulfate (DS) displays peculiar affinity to apoptotic cells and autoantigens (autoAgs) and that DS-autoAg complexes cooperatively stimulate autoreactive B1 cell responses, we compiled a database of 751 candidate autoAgs from six human cell types. At least 657 of these have been found to be affected by SARS-CoV-2 infection based on currently available multi-omic COVID data, and at least 400 are confirmed targets of autoantibodies in a wide array of autoimmune diseases and cancer. -

WO 2013/064702 A2 10 May 2013 (10.05.2013) P O P C T

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization I International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date WO 2013/064702 A2 10 May 2013 (10.05.2013) P O P C T (51) International Patent Classification: AO, AT, AU, AZ, BA, BB, BG, BH, BN, BR, BW, BY, C12Q 1/68 (2006.01) BZ, CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DK, DM, DO, DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, (21) International Application Number: HN, HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IS, JP, KE, KG, KM, KN, KP, PCT/EP2012/071868 KR, KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LT, LU, LY, MA, MD, (22) International Filing Date: ME, MG, MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, 5 November 20 12 (05 .11.20 12) NO, NZ, OM, PA, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, QA, RO, RS, RU, RW, SC, SD, SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY, TH, TJ, (25) Filing Language: English TM, TN, TR, TT, TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, (26) Publication Language: English ZM, ZW. (30) Priority Data: (84) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every 1118985.9 3 November 201 1 (03. 11.201 1) GB kind of regional protection available): ARIPO (BW, GH, 13/339,63 1 29 December 201 1 (29. 12.201 1) US GM, KE, LR, LS, MW, MZ, NA, RW, SD, SL, SZ, TZ, UG, ZM, ZW), Eurasian (AM, AZ, BY, KG, KZ, RU, TJ, (71) Applicant: DIAGENIC ASA [NO/NO]; Grenseveien 92, TM), European (AL, AT, BE, BG, CH, CY, CZ, DE, DK, N-0663 Oslo (NO). -

Human Social Genomics in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis

Getting “Under the Skin”: Human Social Genomics in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis by Kristen Monét Brown A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Epidemiological Science) in the University of Michigan 2017 Doctoral Committee: Professor Ana V. Diez-Roux, Co-Chair, Drexel University Professor Sharon R. Kardia, Co-Chair Professor Bhramar Mukherjee Assistant Professor Belinda Needham Assistant Professor Jennifer A. Smith © Kristen Monét Brown, 2017 [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0002-9955-0568 Dedication I dedicate this dissertation to my grandmother, Gertrude Delores Hampton. Nanny, no one wanted to see me become “Dr. Brown” more than you. I know that you are standing over the bannister of heaven smiling and beaming with pride. I love you more than my words could ever fully express. ii Acknowledgements First, I give honor to God, who is the head of my life. Truly, without Him, none of this would be possible. Countless times throughout this doctoral journey I have relied my favorite scripture, “And we know that all things work together for good, to them that love God, to them who are called according to His purpose (Romans 8:28).” Secondly, I acknowledge my parents, James and Marilyn Brown. From an early age, you two instilled in me the value of education and have been my biggest cheerleaders throughout my entire life. I thank you for your unconditional love, encouragement, sacrifices, and support. I would not be here today without you. I truly thank God that out of the all of the people in the world that He could have chosen to be my parents, that He chose the two of you. -

Global Proteomic Detection of Native, Stable, Soluble Human Protein Complexes

GLOBAL PROTEOMIC DETECTION OF NATIVE, STABLE, SOLUBLE HUMAN PROTEIN COMPLEXES by Pierre Claver Havugimana A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Molecular Genetics University of Toronto © Copyright by Pierre Claver Havugimana 2012 Global Proteomic Detection of Native, Stable, Soluble Human Protein Complexes Pierre Claver Havugimana Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Molecular Genetics University of Toronto 2012 Abstract Protein complexes are critical to virtually every biological process performed by living organisms. The cellular “interactome”, or set of physical protein-protein interactions, is of particular interest, but no comprehensive study of human multi-protein complexes has yet been reported. In this Thesis, I describe the development of a novel high-throughput profiling method, which I term Fractionomic Profiling-Mass Spectrometry (or FP-MS), in which biochemical fractionation using non-denaturing high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), as an alternative to affinity purification (e.g. TAP tagging) or immuno-precipitation, is coupled with tandem mass spectrometry-based protein identification for the global detection of stably- associated protein complexes in mammalian cells or tissues. Using a cell culture model system, I document proof-of-principle experiments confirming the suitability of this method for monitoring large numbers of soluble, stable protein complexes from either crude protein extracts or enriched sub-cellular compartments. Next, I document how, using orthogonal functional genomics information generated in collaboration with computational biology groups as filters, we applied FP-MS co-fractionation profiling to construct a high-quality map of 622 predicted unique soluble human protein complexes that could be biochemically enriched from HeLa and HEK293 nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts. -

50 Clinical Neurogenetics Brent L

50 Clinical Neurogenetics Brent L. Fogel, Daniel H. Geschwind CHAPTER OUTLINE research has permitted dissection of the cellular machinery supporting the function of the brain and its connections while establishing causal relationships between such dysfunction, GENETICS IN CLINICAL NEUROLOGY human genetic variation, and various neurological diseases. In GENE EXPRESSION, DIVERSITY, AND REGULATION the modern practice of neurology, the use of genetics has DNA to RNA to Protein become widespread, and neurologists are confronted daily with data from an ever-increasing catalog of genetic studies TYPES OF GENETIC VARIATION AND MUTATIONS relating to conditions such as developmental disorders, Rare versus Common Variation dementia, ataxia, neuropathy, and epilepsy, to name but a few. Polymorphisms and Point Mutations The use of genetic information in the clinical evaluation of Structural Chromosomal Abnormalities and Copy neurological disease has expanded dramatically over the past Number Variation (CNV) decade. More efficient techniques for discovering disease genes Repeat Expansion Disorders have led to a greater availability of genetic testing in the clinic. CHROMOSOMAL ANALYSIS AND ABNORMALITIES Approximately one-third of pediatric neurology hospital admissions are related to a genetic diagnosis, and there are DISORDERS OF MENDELIAN INHERITANCE now hundreds of individual genetic tests available to the prac- Autosomal Dominant Disorders ticing neurologist, including several related to common dis- Autosomal Recessive Disorders eases. This number continues to increase rapidly (Fig. 50.1), Sex-Linked (X-Linked) Disorders but is rapidly being supplanted by the clinical availability of exome and genome sequencing, allowing neurologists to MENDELIAN DISEASE GENE IDENTIFICATION BY rapidly survey every gene in human genome for disease- LINKAGE ANALYSIS AND CHROMOSOME MAPPING causing mutations. -

Title 1 Transcriptomic Analysis of Ribosome Biogenesis and Pre-Rrna

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.08.01.454488; this version posted August 1, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. 1 Title 2 Transcriptomic analysis of ribosome biogenesis and pre-rRNA processing during growth 3 stress in Entamoeba histolytica ∗1 4 Sarah Naiyer ,2, Shashi Shekhar Singh2,5, Devinder Kaur2,6, Yatendra Pratap Singh2, Amartya 5 Mukherjee2,3, Alok Bhattacharya4 and Sudha Bhattacharya2,4. 6 2- School of Environmental Sciences, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi, India-110067 7 3- Present Address: Department of Molecular Reproduction, Development and Genetics, Indian 8 Institute of Science Bangalore-560012 9 4- Present Address: Ashoka University, Rajiv Gandhi Education City, Sonipat, Haryana, India - 10 131029 11 5- Present Address: Department of inflammation and Immunity, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, 12 OH, USA- 44195 13 6- Present Address: Central University of Punjab, Bathinda- 151401 14 15 16 17 *-Corresponding author 18 1- Present Address 19 Sarah Naiyer, PhD 20 Department of Immunology and Microbiology 21 University of Illinois at Chicago, USA, 60612 22 Email: [email protected], [email protected] 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.08.01.454488; this version posted August 1, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity.