Molecular Genetic Characterization of Ataxic Movement Disorders in Mouse and Human

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Autoantibodies in Neurological Diseases

Autoantibodies in neurological diseases Hu, Ri, Yo, Tr CV2 Amphiphysin Amphiphysin GM1 Ma/Ta CV2 Amphiphysin Cerebellum Intestine Hippocampus Control transfection CV2 GM2 SOX1 PNMAP 2 (MMa2/Ta) Zic4 PNMP A2 GM3G ITPR1 (MMa2/Ta) RiR CARP YoY RiR GD1G a GAD Hippocampus HEp-2 cells Cerebellum NMDAR (transf. cells) Recoverin HuH Titin Anti-Hu positive Anti-NMDA-receptor positive YoY GD1G b Recoverin Gangliosides MAG HuH GT1b SOS X1 Myelin Aquaporin-4 Titin GQ1G b MOG Zic4 VGKC (LGI1 + CASPR2) Cerebellum Intestine Cerebellum Control transfection NMDA receptors GAD65G AMPA receptors Tr (DNER) GABAB receptors DPPX Control CoC ntrol CoC ntrol IgLON5 Hippocampus HEp-2 cells Optic nerve AQP-4 (transf. cells) Glycine receptors Anti-Yo positive Anti-aquaporin-4 positive AChR Indirect immunofl uorescence EUROLINE Examples of relevant target antigens EUROIMMUN AG · Seekamp 31 · 23560 Lübeck (Germany) · Tel +49 451/5855-0 · Fax 5855-591 · [email protected] · www.euroimmun.com 2 Autoantibodies IIFT pattern Test systems Anti-Hu (ANNA-1*) IIFT: Granular fl uorescence of almost all neuronal nuclei on the substrates cerebellum and hippocampus. The Autoantibodies against basic, RNA- cell nuclei of the plexus myentericus (intestinal tissue) binding proteins of the neuronal cell are also positive. nuclei of the central and peripheral nervous system EUROLINE: Positive reaction of the recombinant Hu antigen (HuD). Associated diseases: encephalomyelitis, subacute sensory neuronopathy (Denny-Brown syndrome), autonomous neuropathy Associated tumours: small-cell lung carcinoma, Cerebellum Intestine neuroblastoma Anti-Ri (ANNA-2*) IIFT: Granular fl uorescence of almost all neuronal nuclei on the substrates cerebellum and hippocampus. The Autoantibodies against neuronal cell substrate intestine (plexus myentericus) shows no reac- nuclei of the central nervous system tion. -

Whole-Genome Microarray Detects Deletions and Loss of Heterozygosity of Chromosome 3 Occurring Exclusively in Metastasizing Uveal Melanoma

Anatomy and Pathology Whole-Genome Microarray Detects Deletions and Loss of Heterozygosity of Chromosome 3 Occurring Exclusively in Metastasizing Uveal Melanoma Sarah L. Lake,1 Sarah E. Coupland,1 Azzam F. G. Taktak,2 and Bertil E. Damato3 PURPOSE. To detect deletions and loss of heterozygosity of disease is fatal in 92% of patients within 2 years of diagnosis. chromosome 3 in a rare subset of fatal, disomy 3 uveal mela- Clinical and histopathologic risk factors for UM metastasis noma (UM), undetectable by fluorescence in situ hybridization include large basal tumor diameter (LBD), ciliary body involve- (FISH). ment, epithelioid cytomorphology, extracellular matrix peri- ϩ ETHODS odic acid-Schiff-positive (PAS ) loops, and high mitotic M . Multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification 3,4 5 (MLPA) with the P027 UM assay was performed on formalin- count. Prescher et al. showed that a nonrandom genetic fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) whole tumor sections from 19 change, monosomy 3, correlates strongly with metastatic death, and the correlation has since been confirmed by several disomy 3 metastasizing UMs. Whole-genome microarray analy- 3,6–10 ses using a single-nucleotide polymorphism microarray (aSNP) groups. Consequently, fluorescence in situ hybridization were performed on frozen tissue samples from four fatal dis- (FISH) detection of chromosome 3 using a centromeric probe omy 3 metastasizing UMs and three disomy 3 tumors with Ͼ5 became routine practice for UM prognostication; however, 5% years’ metastasis-free survival. to 20% of disomy 3 UM patients unexpectedly develop metas- tases.11 Attempts have therefore been made to identify the RESULTS. Two metastasizing UMs that had been classified as minimal region(s) of deletion on chromosome 3.12–15 Despite disomy 3 by FISH analysis of a small tumor sample were found these studies, little progress has been made in defining the key on MLPA analysis to show monosomy 3. -

Implication of a Chromosome 15Q15.2 Locus in Regulating UBR1 and Predisposing Smokers to MGMT Methylation in Lung Shuguang Leng1, Guodong Wu1, Leonard B

Published OnlineFirst July 16, 2015; DOI: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-0243 Cancer Prevention and Epidemiology Research Implication of a Chromosome 15q15.2 Locus in Regulating UBR1 and Predisposing Smokers to MGMT Methylation in Lung Shuguang Leng1, Guodong Wu1, Leonard B. Collins2, Cynthia L.Thomas1, Carmen S.Tellez1, Andrew R. Jauregui3, Maria A. Picchi1, Xiequn Zhang1, Daniel E. Juri1, Dhimant Desai4, Shantu G. Amin4, Richard E. Crowell5, Christine A. Stidley5,Yushi Liu1, James A. Swenberg2, Yong Lin1, Marc G. Wathelet3, Frank D. Gilliland6, and Steven A. Belinsky1 Abstract O6-Methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase (MGMT) is a risk prediction for MGMT methylation. We found that the DNA repair enzyme that protects cells from carcinogenic effects predisposition to MGMT methylation arising from the of alkylating agents; however, MGMT is silenced by promoter 15q15.2 locus involved regulation of the ubiquitin protein hypermethylation during carcinogenesis. A single-nucleotide ligase E3 component UBR1. UBR1 attenuation reduced turn- polymorphism (SNP) in an enhancer in the MGMT promoter over of MGMT protein and increased repair of O6-methylgua- was previously identified to be highly significantly associated nine in nitrosomethylurea-treated human bronchial epithelial with risk for MGMT methylation in lung cancer and sputum cells, while also reducing MGMT promoter activity and abol- from smokers. To further genetic investigations, a genome-wide ishing MGMT induction. Overall, our results substantiate association and replication study was conducted in two smoker reduced gene transcription as a major mechanism for predis- cohorts to identify novel loci for MGMT methylation in sputum position to MGMT methylation in the lungs of smokers, and that were independent of the MGMT enhancer polymorphism. -

Design of a Bioactive Small Molecule That Targets R(AUUCU) Repeats in Spinocerebellar Ataxia 10

ARTICLE Received 24 Jun 2015 | Accepted 18 Apr 2016 | Published 1 Jun 2016 DOI: 10.1038/ncomms11647 OPEN Design of a bioactive small molecule that targets r(AUUCU) repeats in spinocerebellar ataxia 10 Wang-Yong Yang1, Rui Gao2, Mark Southern3, Partha S. Sarkar2 & Matthew D. Disney1 RNA is an important target for chemical probes of function and lead therapeutics; however, it is difficult to target with small molecules. One approach to tackle this problem is to identify compounds that target RNA structures and utilize them to multivalently target RNA. Here we show that small molecules can be identified to selectively bind RNA base pairs by probing a library of RNA-focused small molecules. A small molecule that selectively binds AU base pairs informed design of a dimeric compound (2AU-2) that targets the pathogenic RNA, expanded r(AUUCU) repeats, that causes spinocerebellar ataxia type 10 (SCA10) in patient- derived cells. Indeed, 2AU-2 (50 nM) ameliorates various aspects of SCA10 pathology including improvement of mitochondrial dysfunction, reduced activation of caspase 3, and reduction of nuclear foci. These studies provide a first-in-class chemical probe to study SCA10 RNA toxicity and potentially define broadly applicable compounds targeting RNA AU base pairs in cells. 1 Departments of Chemistry and Neuroscience, The Scripps Research Institute, Scripps Florida, Jupiter, Florida 33458, USA. 2 Mitchell Center for Neurodegenerative Disorders, Department of Neurology, Neuroscience and Cell Biology, University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, Texas 77555, USA. 3 Informatics Core, The Scripps Research Institute, Scripps Florida, Jupiter, Florida 33458, USA. Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to M.D.D. -

AVILA-DISSERTATION.Pdf

LOGOS EX MACHINA: A REASONED APPROACH TOWARD CANCER by Andrew Avila, B. S., M. S. A Dissertation In Biological Sciences Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Approved Lauren Gollahon Chairperson of the Committee Rich Strauss Sean Rice Boyd Butler Richard Watson Peggy Gordon Miller Dean of the Graduate School May, 2012 c 2012, Andrew Avila Texas Tech University, Andrew Avila, May 2012 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to acknowledge the incredible support given to me by my major adviser, Dr. Lauren Gollahon. Without your guidance surely I would not have made it as far as I have. Furthermore, the intellectual exchange I have shared with my advisory committee these long years have propelled me to new heights of inquiry I had not dreamed of even in the most lucid of my imaginings. That their continual intellectual challenges have provoked and evoked a subtle sense of natural wisdom is an ode to their efficacy in guiding the aspirant to the well of knowledge. For this initiation into the mysteries of nature I cannot thank my advisory committee enough. I also wish to thank the Vice President of Research for the fellowship which sustained the initial couple years of my residency at Texas Tech. Furthermore, my appreciation of the support provided to me by the Biology Department, financial and otherwise, cannot be understated. Finally, I also wish to acknowledge the individuals working at the High Performance Computing Center, without your tireless support in maintaining the cluster I would have not have completed the sheer amount of research that I have. -

A New Model for X-Linked Tremor/Ataxia

© 2016. Published by The Company of Biologists Ltd | Disease Models & Mechanisms (2016) 9, 553-562 doi:10.1242/dmm.022848 RESEARCH ARTICLE Spontaneous shaker rat mutant – a new model for X-linked tremor/ ataxia Karla P. Figueroa1, Sharan Paul1, Tito Calì2, Raffaele Lopreiato2, Sukanya Karan1, Martina Frizzarin2, Darren Ames3, Ginevra Zanni4, Marisa Brini5, Warunee Dansithong1, Brett Milash3, Daniel R. Scoles1, Ernesto Carafoli6 and Stefan M. Pulst1,* ABSTRACT mode of inheritance. Here, we describe the genetic analysis of the The shaker rat is an X-linked recessive spontaneous model of shaker rat, a model of Purkinje cell (PC) degeneration. This mutant progressive Purkinje cell (PC) degeneration exhibiting a shaking arose spontaneously and was observed in Sprague Dawley (SD) ataxia and wide stance. Generation of Wistar Furth (WF)/Brown outbred stock in 1991 at Saint Louis University, first described by Norwegian (BN) F1 hybrids and genetic mapping of F2 sib-sib La Regina et al. (1992), and the phenotype of whole-body tremor, ‘ ’ offspring using polymorphic markers narrowed the candidate gene ataxia and wide stance designated as shaker . The shaker trait was region to 26 Mbp denoted by the last recombinant genetic marker reported as an X-linked recessive trait. DXRat21 at 133 Mbp to qter (the end of the long arm). In the WF Various animal models of spontaneously occurring mutants that background, the shaker mutation has complete penetrance, results in parallel some aspects of human hereditary ataxia have been a stereotypic phenotype and there is a narrow window for age of reported; for example, weaver, lurcher, stumbler, tottering and disease onset; by contrast, the F2 hybrid phenotype was more varied, teetering mice (Chou et al., 1991; Frankel et al., 1994; Green and with a later age of onset and likely non-penetrance of the mutation. -

1 Supporting Information for a Microrna Network Regulates

Supporting Information for A microRNA Network Regulates Expression and Biosynthesis of CFTR and CFTR-ΔF508 Shyam Ramachandrana,b, Philip H. Karpc, Peng Jiangc, Lynda S. Ostedgaardc, Amy E. Walza, John T. Fishere, Shaf Keshavjeeh, Kim A. Lennoxi, Ashley M. Jacobii, Scott D. Rosei, Mark A. Behlkei, Michael J. Welshb,c,d,g, Yi Xingb,c,f, Paul B. McCray Jr.a,b,c Author Affiliations: Department of Pediatricsa, Interdisciplinary Program in Geneticsb, Departments of Internal Medicinec, Molecular Physiology and Biophysicsd, Anatomy and Cell Biologye, Biomedical Engineeringf, Howard Hughes Medical Instituteg, Carver College of Medicine, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA-52242 Division of Thoracic Surgeryh, Toronto General Hospital, University Health Network, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada-M5G 2C4 Integrated DNA Technologiesi, Coralville, IA-52241 To whom correspondence should be addressed: Email: [email protected] (M.J.W.); yi- [email protected] (Y.X.); Email: [email protected] (P.B.M.) This PDF file includes: Materials and Methods References Fig. S1. miR-138 regulates SIN3A in a dose-dependent and site-specific manner. Fig. S2. miR-138 regulates endogenous SIN3A protein expression. Fig. S3. miR-138 regulates endogenous CFTR protein expression in Calu-3 cells. Fig. S4. miR-138 regulates endogenous CFTR protein expression in primary human airway epithelia. Fig. S5. miR-138 regulates CFTR expression in HeLa cells. Fig. S6. miR-138 regulates CFTR expression in HEK293T cells. Fig. S7. HeLa cells exhibit CFTR channel activity. Fig. S8. miR-138 improves CFTR processing. Fig. S9. miR-138 improves CFTR-ΔF508 processing. Fig. S10. SIN3A inhibition yields partial rescue of Cl- transport in CF epithelia. -

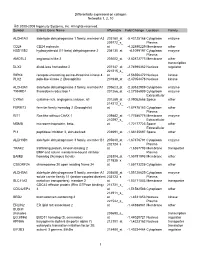

Differentially Expressed on Collagen Networks 1, 2, 10 © 2000-2009 Ingenuity Systems, Inc. All Rights Reserved. Symbol Entrez

Differentially expressed on collagen Networks 1, 2, 10 © 2000-2009 Ingenuity Systems, Inc. All rights reserved. Symbol Entrez Gene Name Affymetrix Fold Change Location Family ALDH1A3 aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 family, member A3 203180_at -5.43125168 Cytoplasm enzyme 209772_s_ Plasma CD24 CD24 molecule at -4.32890229 Membrane other HSD11B2 hydroxysteroid (11-beta) dehydrogenase 2 204130_at -4.1099197 Cytoplasm enzyme Plasma AMOTL2 angiomotin like 2 203002_at -2.82872773 Membrane other transcription DLX2 distal-less homeobox 2 207147_at -2.74996362 Nucleus regulator 221215_s_ RIPK4 receptor-interacting serine-threonine kinase 4 at -2.56556472 Nucleus kinase PLK2 polo-like kinase 2 (Drosophila) 201939_at -2.47054478 Nucleus kinase ALDH3A1 aldehyde dehydrogenase 3 family, memberA1 205623_at -2.30532989 Cytoplasm enzyme TXNRD1 thioredoxin reductase 1 201266_at -2.27936909 Cytoplasm enzyme Extracellular CYR61 cysteine-rich, angiogenic inducer, 61 201289_at -2.09052668 Space other 214212_x_ FERMT2 fermitin family homolog 2 (Drosophila) at -1.87478183 Cytoplasm other Plasma RIT1 Ras-like without CAAX 1 209882_at -1.77586775 Membrane enzyme 210297_s_ Extracellular MSMB microseminoprotein, beta- at -1.72177723 Space other Extracellular PI3 peptidase inhibitor 3, skin-derived 203691_at -1.68135697 Space other ALDH3B1 aldehyde dehydrogenase 3 family, member B1 205640_at -1.67376791 Cytoplasm enzyme 202124_s_ Plasma TRAK2 trafficking protein, kinesin binding 2 at -1.6367793 Membrane transporter BMP and activin membrane-bound inhibitor Plasma BAMBI -

Supplementary Table 1: Adhesion Genes Data Set

Supplementary Table 1: Adhesion genes data set PROBE Entrez Gene ID Celera Gene ID Gene_Symbol Gene_Name 160832 1 hCG201364.3 A1BG alpha-1-B glycoprotein 223658 1 hCG201364.3 A1BG alpha-1-B glycoprotein 212988 102 hCG40040.3 ADAM10 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 10 133411 4185 hCG28232.2 ADAM11 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 11 110695 8038 hCG40937.4 ADAM12 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 12 (meltrin alpha) 195222 8038 hCG40937.4 ADAM12 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 12 (meltrin alpha) 165344 8751 hCG20021.3 ADAM15 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 15 (metargidin) 189065 6868 null ADAM17 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 17 (tumor necrosis factor, alpha, converting enzyme) 108119 8728 hCG15398.4 ADAM19 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 19 (meltrin beta) 117763 8748 hCG20675.3 ADAM20 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 20 126448 8747 hCG1785634.2 ADAM21 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 21 208981 8747 hCG1785634.2|hCG2042897 ADAM21 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 21 180903 53616 hCG17212.4 ADAM22 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 22 177272 8745 hCG1811623.1 ADAM23 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 23 102384 10863 hCG1818505.1 ADAM28 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 28 119968 11086 hCG1786734.2 ADAM29 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 29 205542 11085 hCG1997196.1 ADAM30 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 30 148417 80332 hCG39255.4 ADAM33 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 33 140492 8756 hCG1789002.2 ADAM7 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 7 122603 101 hCG1816947.1 ADAM8 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 8 183965 8754 hCG1996391 ADAM9 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 9 (meltrin gamma) 129974 27299 hCG15447.3 ADAMDEC1 ADAM-like, -

Transcriptome Sequencing and Genome-Wide Association Analyses Reveal Lysosomal Function and Actin Cytoskeleton Remodeling in Schizophrenia and Bipolar Disorder

Molecular Psychiatry (2015) 20, 563–572 © 2015 Macmillan Publishers Limited All rights reserved 1359-4184/15 www.nature.com/mp ORIGINAL ARTICLE Transcriptome sequencing and genome-wide association analyses reveal lysosomal function and actin cytoskeleton remodeling in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder Z Zhao1,6,JXu2,6, J Chen3,6, S Kim4, M Reimers3, S-A Bacanu3,HYu1, C Liu5, J Sun1, Q Wang1, P Jia1,FXu2, Y Zhang2, KS Kendler3, Z Peng2 and X Chen3 Schizophrenia (SCZ) and bipolar disorder (BPD) are severe mental disorders with high heritability. Clinicians have long noticed the similarities of clinic symptoms between these disorders. In recent years, accumulating evidence indicates some shared genetic liabilities. However, what is shared remains elusive. In this study, we conducted whole transcriptome analysis of post-mortem brain tissues (cingulate cortex) from SCZ, BPD and control subjects, and identified differentially expressed genes in these disorders. We found 105 and 153 genes differentially expressed in SCZ and BPD, respectively. By comparing the t-test scores, we found that many of the genes differentially expressed in SCZ and BPD are concordant in their expression level (q ⩽ 0.01, 53 genes; q ⩽ 0.05, 213 genes; q ⩽ 0.1, 885 genes). Using genome-wide association data from the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium, we found that these differentially and concordantly expressed genes were enriched in association signals for both SCZ (Po10 − 7) and BPD (P = 0.029). To our knowledge, this is the first time that a substantially large number of genes show concordant expression and association for both SCZ and BPD. Pathway analyses of these genes indicated that they are involved in the lysosome, Fc gamma receptor-mediated phagocytosis, regulation of actin cytoskeleton pathways, along with several cancer pathways. -

Strategies and Opportunities for Small Molecule Drug Discovery to Target Neurodegenerative Diseases Andrea I

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.01.020206; this version posted April 2, 2020. The copyright holder has placed this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) in the Public Domain. It is no longer restricted by copyright. Anyone can legally share, reuse, remix, or adapt this material for any purpose without crediting the original authors. Defining the Neural Kinome: Strategies and Opportunities for Small Molecule Drug Discovery to Target Neurodegenerative Diseases Andrea I. Krahn, Carrow Wells, David H. Drewry, Lenore K. Beitel, Thomas M. Durcan, Alison D. Axtman* ABSTRACT: Kinases are highly tractable drug targets that have reached unparalleled success in fields such as cancer but whose potential has not yet been realized in neuroscience. There are currently 55 approved small molecule kinase-targeting drugs, 48 of which have an anti-cancer indication. The intrinsic complexity linked to central nervous system (CNS) drug development and a lack of validated targets has hindered progress in developing kinase inhibitors for CNS disorders when compared to other therapeutic areas such as oncology. Identification and/or characterization of new kinases as potential drug targets for neurodegenerative diseases will create opportunities for development of CNS drugs in the future. The track record of kinase inhibitors in other disease indications supports the idea that with the best targets identified small molecule kinase modulators will become impactful therapeutics for neurodegenerative diseases. KEYWORDS: kinase, neurodegeneration, -

Epigenetic Alterations of Chromosome 3 Revealed by Noti-Microarrays in Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma

Hindawi Publishing Corporation BioMed Research International Volume 2014, Article ID 735292, 9 pages http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2014/735292 Research Article Epigenetic Alterations of Chromosome 3 Revealed by NotI-Microarrays in Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma Alexey A. Dmitriev,1,2 Evgeniya E. Rudenko,3 Anna V. Kudryavtseva,1,2 George S. Krasnov,1,4 Vasily V. Gordiyuk,3 Nataliya V. Melnikova,1 Eduard O. Stakhovsky,5 Oleksii A. Kononenko,5 Larissa S. Pavlova,6 Tatiana T. Kondratieva,6 Boris Y. Alekseev,2 Eleonora A. Braga,7,8 Vera N. Senchenko,1 and Vladimir I. Kashuba3,9 1 Engelhardt Institute of Molecular Biology, Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow 119991, Russia 2 P.A. Herzen Moscow Oncology Research Institute, Ministry of Healthcare of the Russian Federation, Moscow 125284, Russia 3 Institute of Molecular Biology and Genetics, Ukrainian Academy of Sciences, Kiev 03680, Ukraine 4 Mechnikov Research Institute for Vaccines and Sera, Russian Academy of Medical Sciences, Moscow 105064, Russia 5 National Cancer Institute, Kiev 03022, Ukraine 6 N.N. Blokhin Russian Cancer Research Center, Russian Academy of Medical Sciences, Moscow 115478, Russia 7 Institute of General Pathology and Pathophysiology, Russian Academy of Medical Sciences, Moscow 125315, Russia 8 Research Center of Medical Genetics, Russian Academy of Medical Sciences, Moscow 115478, Russia 9 DepartmentofMicrobiology,TumorandCellBiology,KarolinskaInstitute,17177Stockholm,Sweden Correspondence should be addressed to Alexey A. Dmitriev; alex [email protected] Received 19 February 2014; Revised 10 April 2014; Accepted 17 April 2014; Published 22 May 2014 Academic Editor: Carole Sourbier Copyright © 2014 Alexey A. Dmitriev et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.