Africa and Liberia in World Politics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kwame Nkrumah and the Pan- African Vision: Between Acceptance and Rebuttal

Austral: Brazilian Journal of Strategy & International Relations e-ISSN 2238-6912 | ISSN 2238-6262| v.5, n.9, Jan./Jun. 2016 | p.141-164 KWAME NKRUMAH AND THE PAN- AFRICAN VISION: BETWEEN ACCEPTANCE AND REBUTTAL Henry Kam Kah1 Introduction The Pan-African vision of a United of States of Africa was and is still being expressed (dis)similarly by Africans on the continent and those of Afri- can descent scattered all over the world. Its humble origins and spread is at- tributed to several people based on their experiences over time. Among some of the advocates were Henry Sylvester Williams, Marcus Garvey and George Padmore of the diaspora and Peter Abrahams, Jomo Kenyatta, Sekou Toure, Julius Nyerere and Kwame Nkrumah of South Africa, Kenya, Guinea, Tanza- nia and Ghana respectively. The different pan-African views on the African continent notwithstanding, Kwame Nkrumah is arguably in a class of his own and perhaps comparable only to Mwalimu Julius Nyerere. Pan-Africanism became the cornerstone of his struggle for the independence of Ghana, other African countries and the political unity of the continent. To transform this vision into reality, Nkrumah mobilised the Ghanaian masses through a pop- ular appeal. Apart from his eloquent speeches, he also engaged in persuasive writings. These writings have survived him and are as appealing today as they were in the past. Kwame Nkrumah ceased every opportunity to persuasively articulate for a Union Government for all of Africa. Due to his unswerving vision for a Union Government for Africa, the visionary Kwame Nkrumah created a microcosm of African Union through the Ghana-Guinea and then Ghana-Guinea-Mali Union. -

Adult Authority, Social Conflict, and Youth Survival Strategies in Post Civil War Liberia

‘Listen, Politics is not for Children:’ Adult Authority, Social Conflict, and Youth Survival Strategies in Post Civil War Liberia. DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Henryatta Louise Ballah Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2012 Dissertation Committee: Drs. Ousman Kobo, Advisor Antoinette Errante Ahmad Sikianga i Copyright by Henryatta Louise Ballah 2012 ii Abstract This dissertation explores the historical causes of the Liberian civil war (1989- 2003), with a keen attention to the history of Liberian youth, since the beginning of the Republic in 1847. I carefully analyzed youth engagements in social and political change throughout the country’s history, including the ways by which the civil war impacted the youth and inspired them to create new social and economic spaces for themselves. As will be demonstrated in various chapters, despite their marginalization by the state, the youth have played a crucial role in the quest for democratization in the country, especially since the 1960s. I place my analysis of the youth in deep societal structures related to Liberia’s colonial past and neo-colonial status, as well as the impact of external factors, such as the financial and military support the regime of Samuel Doe received from the United States during the cold war and the influence of other African nations. I emphasize that the socio-economic and political policies implemented by the Americo- Liberians (freed slaves from the U.S.) who settled in the country beginning in 1822, helped lay the foundation for the civil war. -

Cultural Production in Andrea Levy's Small Island Author: Alicia E

ENTERTEXT Identity as Cultural Production in Andrea Levy's Small Island Author: Alicia E. Ellis Source: EnterText, “Special Issue on Andrea Levy 9,” (2012): 69-83. Abstract Andrea Levy's Small Island (2004) presents a counter-history of the period before and after World War II (1939-1945) when men and women from the Caribbean volunteered for all branches of the British armed services and many eventually immigrated to London after the war officially ended in 1945. Her historical novel moves back and forth between 1924 and 1948 as well as across national borders and cultures. Levy’s novel, written more than fifty years after the first Windrush arrival, creates a common narrative of nation and identity in order to understand the experiences of Black people in Britain. Small Island—structured around four competing voices whose claims of textual, personal and historical truth must be acknowledged—refuses to establish a singular articulation of the experience of migration and empire. In this essay, I focus on discrete moments in the “Prologue” in Levy’s Small Island in order to think through the formation of discursive identity through the encounter with others and the necessity of accommodating difference. Small Island forecloses the possibility of addressing modern multiculturalism as a purported ‘happy ending’ in light of Levy’s formulation of the Windrush moment as disruptive, violent, and overwhelmed by flawed characters. Yet, through the space of writing, she also invites the reader to experience moments of encounter and negotiate the often competing claims on nationhood, citizenship, and culture. Identity as Cultural Production in Andrea Levy's Small Island Alicia E. -

Barthé, Darryl G. Jr.Pdf

A University of Sussex PhD thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details Becoming American in Creole New Orleans: Family, Community, Labor and Schooling, 1896-1949 Darryl G. Barthé, Jr. Doctorate of Philosophy in History University of Sussex Submitted May 2015 University of Sussex Darryl G. Barthé, Jr. (Doctorate of Philosophy in History) Becoming American in Creole New Orleans: Family, Community, Labor and Schooling, 1896-1949 Summary: The Louisiana Creole community in New Orleans went through profound changes in the first half of the 20th-century. This work examines Creole ethnic identity, focusing particularly on the transition from Creole to American. In "becoming American," Creoles adapted to a binary, racialized caste system prevalent in the Jim Crow American South (and transformed from a primarily Francophone/Creolophone community (where a tripartite although permissive caste system long existed) to a primarily Anglophone community (marked by stricter black-white binaries). These adaptations and transformations were facilitated through Creole participation in fraternal societies, the organized labor movement and public and parochial schools that provided English-only instruction. -

A Short History of the First Liberian Republic

Joseph Saye Guannu A Short History of the First Liberian Republic Third edition Star*Books Contents Preface viii About the author x The new state and its government Introduction The Declaration of Independence and Constitution Causes leading to the Declaration of Independence The Constitutional Convention The Constitution The kind of state and system of government 4 The kind of state Organization of government System of government The l1ag and seal of Liberia The exclusion and inclusion of ethnic Liberians The rulers and their administrations 10 Joseph Jenkins Roberts Stephen Allen Benson Daniel Bashiel Warner James Spriggs Payne Edward James Roye James Skirving Smith Anthony William Gardner Alfred Francis Russell Hilary Richard Wright Johnson JosephJames Cheeseman William David Coleman Garretson Wilmot Gibson Arthur Barclay Daniel Edward Howard Charles Dunbar Burgess King Edwin James Barclay William Vacanarat Shadrach Tubman William Richard Tolbert PresidentiaI succession in Liberian history 36 BeforeRoye After Roye iii A Short HIstory 01 the First lIberlJn Republlc The expansion of presidential powers 36 The socio-political factors The economic factors Abrief history of party politics 31 Before the True Whig Party The True Whig Party Interior policy of the True Whig Party Major oppositions to the True Whig Party The Election of 1927 The Election of 1951 The Election of 1955 The plot that failed Questions Activities 2 Territorial expansion of, and encroachment on, Liberia 4~ Introduction 41 Two major reasons for expansion 4' Economic -

"Free Negroes" - the Development of Early English Jamaica and the Birth of Jamaican Maroon Consciousness, 1655-1670

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University History Theses Department of History 12-16-2015 "Free Negroes" - The Development of Early English Jamaica and the Birth of Jamaican Maroon Consciousness, 1655-1670 Patrick John Nichols Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/history_theses Recommended Citation Nichols, Patrick John, ""Free Negroes" - The Development of Early English Jamaica and the Birth of Jamaican Maroon Consciousness, 1655-1670." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2015. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/history_theses/100 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of History at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “FREE NEGROES” – THE DEVELOPMENT OF EARLY ENGLISH JAMAICA AND THE BIRTH OF JAMAICAN MAROON CONSCIOUSNESS, 1655-1670 by PATRICK JOHN NICHOLS Under the Direction of Harcourt Fuller, PhD ABSTRACT The English conquest of Jamaica in 1655 was a turning point in the history of Atlantic World colonialism. Conquest displaced the Spanish colony and its subjects, some of who fled into the mountainous interior of Jamaica and assumed lives in isolation. This project reconstructs the historical experiences of the “negro” populations of Spanish and English Jamaica, which included its “free black”, “mulattoes”, indigenous peoples, and others, and examines how English cosmopolitanism and distinct interactions laid the groundwork for and informed the syncretic identities and communities that emerged decades later. Upon the framework of English conquest within the West Indies, I explore the experiences of one such settlement alongside the early English colony of Jamaica to understand how a formal relationship materialized between the entities and how its course inflected the distinct socio-political identity and emergent political agency embodied by the Jamaican Maroons. -

Pan-African History: Political Figures from Africa and the Diaspora Since 1787 Hakim Adi University of Chichester, [email protected]

African Diaspora Archaeology Newsletter Volume 8 Article 6 Issue 4 September 2005 7-1-2005 Pan-African History: Political Figures from Africa and the Diaspora since 1787 Hakim Adi University of Chichester, [email protected] Marika Sherwood University of London Robert Trent Vinson Washington University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/adan Part of the African American Studies Commons, African History Commons, African Languages and Societies Commons, African Studies Commons, American Art and Architecture Commons, American Material Culture Commons, Archaeological Anthropology Commons, Biological and Physical Anthropology Commons, Folklore Commons, Other American Studies Commons, Other History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons, Other International and Area Studies Commons, Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, Social History Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Adi, Hakim; Sherwood, Marika; and Vinson, Robert Trent (2005) "Pan-African History: Political Figures from Africa and the Diaspora since 1787," African Diaspora Archaeology Newsletter: Vol. 8 : Iss. 4 , Article 6. Available at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/adan/vol8/iss4/6 This Book Reviews is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in African Diaspora Archaeology Newsletter by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Adi et al.: Pan-African History: Political Figures from Africa and the Diaspo Book Review H-NET BOOK REVIEW Published by H-SAfrica, http://www.h-net.org/~safrica/ (April, 2005) and H-Atlantic, http://www.h-net.org/~atlantic (June 2005). Hakim Adi and Marika Sherwood. -

TRC of Liberia Final Report Volum Ii

REPUBLIC OF LIBERIA FINAL REPORT VOLUME II: CONSOLIDATED FINAL REPORT This volume constitutes the final and complete report of the TRC of Liberia containing findings, determinations and recommendations to the government and people of Liberia Volume II: Consolidated Final Report Table of Contents List of Abbreviations <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<............. i Acknowledgements <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<... iii Final Statement from the Commission <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<............... v Quotations <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<. 1 1.0 Executive Summary <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<< 2 1.1 Mandate of the TRC <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<< 2 1.2 Background of the Founding of Liberia <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<... 3 1.3 History of the Conflict <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<................ 4 1.4 Findings and Determinations <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<< 6 1.5 Recommendations <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<... 12 1.5.1 To the People of Liberia <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<. 12 1.5.2 To the Government of Liberia <<<<<<<<<<. <<<<<<. 12 1.5.3 To the International Community <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<. 13 2.0 Introduction <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<. 14 2.1 The Beginning <<................................................................................................... 14 2.2 Profile of Commissioners of the TRC of Liberia <<<<<<<<<<<<.. 14 2.3 Profile of International Technical Advisory Committee <<<<<<<<<. 18 2.4 Secretariat and Specialized Staff <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<. 20 2.5 Commissioners, Specialists, Senior Staff, and Administration <<<<<<.. 21 2.5.1 Commissioners <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<. 22 2.5.2 International Technical Advisory -

PELLIZZARI-DISSERTATION-2020.Pdf (3.679Mb)

A Struggle for Empire: Resistance and Reform in the British Atlantic World, 1760-1778 The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Pellizzari, Peter. 2020. A Struggle for Empire: Resistance and Reform in the British Atlantic World, 1760-1778. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link https://nrs.harvard.edu/URN-3:HUL.INSTREPOS:37365752 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA A Struggle for Empire: Resistance and Reform in the British Atlantic World, 1760-1778 A dissertation presented by Peter Pellizzari to The Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of History Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts May 2020 © 2020 Peter Pellizzari All rights reserved. Dissertation Advisors: Jane Kamensky and Jill Lepore Peter Pellizzari A Struggle for Empire: Resistance and Reform in the British Atlantic World, 1760-1778 Abstract The American Revolution not only marked the end of Britain’s control over thirteen rebellious colonies, but also the beginning of a division among subsequent historians that has long shaped our understanding of British America. Some historians have emphasized a continental approach and believe research should look west, toward the people that inhabited places outside the traditional “thirteen colonies” that would become the United States, such as the Gulf Coast or the Great Lakes region. -

Jane W V. Moses Thomas Complaint

Case 2:18-cv-00569-PBT Document 1 Filed 02/12/18 Page 1 of 38 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF PENNSYLVANIA JANE W, in her individual capacity, and in her capacity as the personal representative of the estates of her relatives, James W, Julie W, and Jen W; Civil Action No. ________________ JOHN X, in his individual capacity, and in his capacity as the personal representative JURY TRIAL REQUESTED of the estates of his relatives, Jane X, Julie X, James X, and Joseph X; JOHN Y, in his individual capacity; AND JOHN Z, in his individual capacity, Plaintiffs, v. MOSES W. THOMAS, Defendant. COMPLAINT Plaintiffs Jane W, John X, John Y, and John Z in their personal capacities and on behalf of their decedent relatives (collectively “Plaintiffs”), complain and allege as follows. PRELIMINARY STATEMENT 1. This case arises from the brutal massacre of unarmed civilians seeking shelter in St. Peter’s Lutheran Church (the “Lutheran Church” or the “Church”) in Monrovia, Liberia (the “Lutheran Church Massacre” or the “Massacre”). The Church was a designated Red Cross humanitarian aid center sheltering civilians displaced from the growing violence in Liberia’s countryside and in the capital city of Monrovia. The Lutheran Church Massacre was one of the largest attacks on civilians during Liberia’s two back-to-back civil wars, the first of 106612680v.1 Case 2:18-cv-00569-PBT Document 1 Filed 02/12/18 Page 2 of 38 which was a seven-year armed conflict beginning in 1989 that took the lives of over 200,000 individuals and displaced half the nation’s population. -

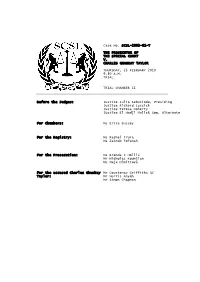

Taylor Trial Transcript

Case No. SCSL-2003-01-T THE PROSECUTOR OF THE SPECIAL COURT V. CHARLES GHANKAY TAYLOR THURSDAY, 25 FEBRUARY 2010 9.30 A.M. TRIAL TRIAL CHAMBER II Before the Judges: Justice Julia Sebutinde, Presiding Justice Richard Lussick Justice Teresa Doherty Justice El Hadji Malick Sow, Alternate For Chambers: Ms Erica Bussey For the Registry: Ms Rachel Irura Ms Zainab Fofanah For the Prosecution: Ms Brenda J Hollis Mr Nicholas Koumjian Ms Maja Dimitrova For the accused Charles Ghankay Mr Courtenay Griffiths QC Taylor: Mr Morris Anyah Mr Simon Chapman CHARLES TAYLOR Page 35995 25 FEBRUARY 2010 OPEN SESSION 1 Thursday, 25 February 2010 2 [Open session] 3 [The accused present] 4 [Upon commencing at 9.30 a.m.] 09:29:10 5 PRESIDING JUDGE: Good morning. We will take appearances, 6 please. 7 MR KOUMJIAN: Good morning, Madam President, your Honours, 8 counsel opposite. For the Prosecution this morning, Brenda J 9 Hollis, Maja Dimitrova and myself Nicolas Koumjian. 09:33:35 10 MR ANYAH: Good morning, Madam President. Good morning, 11 your Honours. Good morning, counsel opposite. Appearing for the 12 Defence this morning are Courtenay Griffiths QC and myself Morris 13 Anyah. Thank you. 14 MR GRIFFITHS: Madam President, can I raise a matter which 09:33:49 15 was brought to my notice by the Court Manager this morning. 16 Apparently Mr Taylor doesn't have access to LiveNote at the 17 moment. That really concerns me, because from our point of view 18 it's imperative that the defendant, of all people in this 19 courtroom, be able to follow the proceedings. -

Liberian Studies Journal

VOLUME XIV 1989 NUMBER 2 LIBERIAN STUDIES JOURNAL r 8 °W LIBERIA -8 °N 8 °N- MONSERRADO MARGIBI MARYLAND Geography Department 10 °W University of Pittsburgh at Johnstown 8oW 1 Published by THE LIBERIAN STUDIES ASSOCIATION, INC. PDF compression, OCR, web optimization using a watermarked evaluation copy of CVISION PDFCompressor Cover map: compiled by William Kory, cartography work by Jodie Molnar; Geography Department, University of Pittsburgh at Johnstown. PDF compression, OCR, web optimization using a watermarked evaluation copy of CVISION PDFCompressor VOLUME XIV 1989 NUMBER 2 LIBERIAN STUDIES JOURNAL Editor D. Elwood Dunn The University of the South Associate Editor Similih M. Cordor Kennesaw College Book Review Editor Dalvan M. Coger Memphis State University EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD Bertha B. Azango Lawrence B. Breitborde University of Liberia Beloit College Christopher Clapham Warren L. d'Azevedo Lancaster University University of Nevada Reno Henrique F. Tokpa Thomas E. Hayden Cuttington University College Africa Faith and Justice Network Svend E. Holsoe J. Gus Liebenow University of Delaware Indiana University Corann Okorodudu Glassboro State College Edited at the Department of Political Science, The University of the South PDF compression, OCR, web optimization using a watermarked evaluation copy of CVISION PDFCompressor CONTENTS THE LIBERIAN ECONOMY ON APRIL 1980: SOME REFLECTIONS 1 by Ellen Johnson Sirleaf COGNITIVE ASPECTS OF AGRICULTURE AMONG THE KPELLE: KPELLE FARMING THROUGH KPELLE EYES 23 by John Gay "PACIFICATION" UNDER PRESSURE: A POLITICAL ECONOMY OF LIBERIAN INTERVENTION IN NIMBA 1912 -1918 ............ 44 by Martin Ford BLACK, CHRISTIAN REPUBLICANS: DELEGATES TO THE 1847 LIBERIAN CONSTITUTIONAL CONVENTION ........................ 64 by Carl Patrick Burrowes TRIBE AND CHIEFDOM ON THE WINDWARD COAST 90 by Warren L.