Harry Connick, Jr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Love, Oh Love, Oh Careless Love

Love, Oh Love, Oh Careless Love Careless Love is perhaps the most enduring of traditional folk songs. Of obscure origins, the song’s message is that “careless love” could care less who it hurts in the process. Although the lyrics have changed from version to version, the words usually speak of the pain and heartbreak brought on by love that can take one totally by surprise. And then things go terribly wrong. In many instances, the song’s narrator threatens to kill his or her errant lover. “Love is messy like a po-boy – leaving you drippin’ in debris.” Now, this concept of love is not the sentiment of this author, but, for some, love does not always go right. Countless artists have recorded Careless Love. Rare photo of “Buddy” Bolden Lonnie Johnson New Orleans cornetist and early jazz icon Charles Joseph “Buddy” Bolden played this song and made it one of the best known pieces in his band’s repertory in the early 1900s, and it has remained both a jazz standard and blues standard. In fact, it’s a folk, blues, country and jazz song all rolled into one. Bessie Smith, the Empress of the Blues, cut an extraordinary recording of the song in 1925. Lonnie Johnson of New Orleans recorded it in 1928. It is Pete Seeger’s favorite folk song. Careless Love has been recorded by Louis Armstrong, Ray Charles, Bob Dylan and Johnny Cash. Fats Domino recorded his version in 1951. Crescent City jazz clarinetist George Lewis (born Joseph Louis Francois Zenon, 1900 – 1968) played it, as did other New Orleans performers, such as Dr. -

FAHRENHEIT 451 by Ray Bradbury This One, with Gratitude, Is for DON CONGDON

FAHRENHEIT 451 by Ray Bradbury This one, with gratitude, is for DON CONGDON. FAHRENHEIT 451: The temperature at which book-paper catches fire and burns PART I: THE HEARTH AND THE SALAMANDER IT WAS A PLEASURE TO BURN. IT was a special pleasure to see things eaten, to see things blackened and changed. With the brass nozzle in his fists, with this great python spitting its venomous kerosene upon the world, the blood pounded in his head, and his hands were the hands of some amazing conductor playing all the symphonies of blazing and burning to bring down the tatters and charcoal ruins of history. With his symbolic helmet numbered 451 on his stolid head, and his eyes all orange flame with the thought of what came next, he flicked the igniter and the house jumped up in a gorging fire that burned the evening sky red and yellow and black. He strode in a swarm of fireflies. He wanted above all, like the old joke, to shove a marshmallow on a stick in the furnace, while the flapping pigeon- winged books died on the porch and lawn of the house. While the books went up in sparkling whirls and blew away on a wind turned dark with burning. Montag grinned the fierce grin of all men singed and driven back by flame. He knew that when he returned to the firehouse, he might wink at himself, a minstrel man, Does% burntcorked, in the mirror. Later, going to sleep, he would feel the fiery smile still gripped by his Montag% face muscles, in the dark. -

Aaamc Issue 9 Chrono

of renowned rhythm and blues artists from this same time period lip-synch- ing to their hit recordings. These three aaamc mission: collections provide primary source The AAAMC is devoted to the collection, materials for researchers and students preservation, and dissemination of materi- and, thus, are invaluable additions to als for the purpose of research and study of our growing body of materials on African American music and culture. African American music and popular www.indiana.edu/~aaamc culture. The Archives has begun analyzing data from the project Black Music in Dutch Culture by annotating video No. 9, Fall 2004 recordings made during field research conducted in the Netherlands from 1998–2003. This research documents IN THIS ISSUE: the performance of African American music by Dutch musicians and the Letter ways this music has been integrated into the fabric of Dutch culture. The • From the Desk of the Director ...........................1 “The legacy of Ray In the Vault Charles is a reminder • Donations .............................1 of the importance of documenting and • Featured Collections: preserving the Nelson George .................2 achievements of Phyl Garland ....................2 creative artists and making this Arizona Dranes.................5 information available to students, Events researchers, Tribute.................................3 performers, and the • Ray Charles general public.” 1930-2004 photo by Beverly Parker (Nelson George Collection) photo by Beverly Parker (Nelson George Visiting Scholars reminder of the importance of docu- annotation component of this project is • Scot Brown ......................4 From the Desk menting and preserving the achieve- part of a joint initiative of Indiana of the Director ments of creative artists and making University and the University of this information available to students, Michigan that is funded by the On June 10, 2004, the world lost a researchers, performers, and the gener- Andrew W. -

Jazz Quartess Songlist Pop, Motown & Blues

JAZZ QUARTESS SONGLIST POP, MOTOWN & BLUES One Hundred Years A Thousand Years Overjoyed Ain't No Mountain High Enough Runaround Ain’t That Peculiar Same Old Song Ain’t Too Proud To Beg Sexual Healing B.B. King Medley Signed, Sealed, Delivered Boogie On Reggae Woman Soul Man Build Me Up Buttercup Stop In The Name Of Love Chasing Cars Stormy Monday Clocks Summer In The City Could It Be I’m Fallin’ In Love? Superstition Cruisin’ Sweet Home Chicago Dancing In The Streets Tears Of A Clown Everlasting Love (This Will Be) Time After Time Get Ready Saturday in the Park Gimme One Reason Signed, Sealed, Delivered Green Onions The Scientist Groovin' Up On The Roof Heard It Through The Grapevine Under The Boardwalk Hey, Bartender The Way You Do The Things You Do Hold On, I'm Coming Viva La Vida How Sweet It Is Waste Hungry Like the Wolf What's Going On? Count on Me When Love Comes To Town Dancing in the Moonlight Workin’ My Way Back To You Every Breath You Take You’re All I Need . Every Little Thing She Does Is Magic You’ve Got a Friend Everything Fire and Rain CONTEMPORARY BALLADS Get Lucky A Simple Song Hey, Soul Sister After All How Sweet It Is All I Do Human Nature All My Life I Believe All In Love Is Fair I Can’t Help It All The Man I Need I Can't Help Myself Always & Forever I Feel Good Amazed I Was Made To Love Her And I Love Her I Saw Her Standing There Baby, Come To Me I Wish Back To One If I Ain’t Got You Beautiful In My Eyes If You Really Love Me Beauty And The Beast I’ll Be Around Because You Love Me I’ll Take You There Betcha By Golly -

Mood Music Programs

MOOD MUSIC PROGRAMS MOOD: 2 Pop Adult Contemporary Hot FM ‡ Current Adult Contemporary Hits Hot Adult Contemporary Hits Sample Artists: Andy Grammer, Taylor Swift, Echosmith, Ed Sample Artists: Selena Gomez, Maroon 5, Leona Lewis, Sheeran, Hozier, Colbie Caillat, Sam Hunt, Kelly Clarkson, X George Ezra, Vance Joy, Jason Derulo, Train, Phillip Phillips, Ambassadors, KT Tunstall Daniel Powter, Andrew McMahon in the Wilderness Metro ‡ Be-Tween Chic Metropolitan Blend Kid-friendly, Modern Pop Hits Sample Artists: Roxy Music, Goldfrapp, Charlotte Gainsbourg, Sample Artists: Zendaya, Justin Bieber, Bella Thorne, Cody Hercules & Love Affair, Grace Jones, Carla Bruni, Flight Simpson, Shane Harper, Austin Mahone, One Direction, Facilities, Chromatics, Saint Etienne, Roisin Murphy Bridgit Mendler, Carrie Underwood, China Anne McClain Pop Style Cashmere ‡ Youthful Pop Hits Warm cosmopolitan vocals Sample Artists: Taylor Swift, Justin Bieber, Kelly Clarkson, Sample Artists: The Bird and The Bee, Priscilla Ahn, Jamie Matt Wertz, Katy Perry, Carrie Underwood, Selena Gomez, Woon, Coldplay, Kaskade Phillip Phillips, Andy Grammer, Carly Rae Jepsen Divas Reflections ‡ Dynamic female vocals Mature Pop and classic Jazz vocals Sample Artists: Beyonce, Chaka Khan, Jennifer Hudson, Tina Sample Artists: Ella Fitzgerald, Connie Evingson, Elivs Turner, Paloma Faith, Mary J. Blige, Donna Summer, En Vogue, Costello, Norah Jones, Kurt Elling, Aretha Franklin, Michael Emeli Sande, Etta James, Christina Aguilera Bublé, Mary J. Blige, Sting, Sachal Vasandani FM1 ‡ Shine -

Press Release for Fatherhood

Stalwart bassist Ben Wolfe is proud to announce the August 30th release of his new album, Fatherhood - a heartfelt body of work which pays tribute to the bassist’s father, Dan Wolfe who passed away in 2018. This ten-track collection of nine originals and one cover also serves as a meditation on what it means for Ben to be a father to his own son, Milo. With Fatherhood, the bassist and composer made a conscious decision to step off the fast lane for a moment and make music of introspection and mourning. “I made this record in ways I knew my father would have encouraged” - that meant choosing the best studio, the best musicians, self-funding the entire project, and making wise decisions throughout. Ben is thrilled to have this record brought to fruition by a collection of both familiar collaborators and young phenoms - the bassist is joined by trumper Giveton Gelin, saxophonists Immanuel Wilkins, Ruben Fox, JD Allen, trombonist Steve Davis, pianists Luis Perdomo and Orrin Evans, vibraphonist Joel Ross and drummer Donald Edwards. As on two previous recording sessions, Ben drafted the Grammy- nominated violinist Jesse Mills to put together a stellar string quartet, which features Mills alongside Goergy Valtchev on violin, Kenji Bunch on viola and Wolfram Koessel on cello. Mindful of his father’s judicious approach to performance, Ben surmises that “this record is about the overall sound of the ensemble.” Ben and his dad experienced the customary roller coaster ride typical of father-son relationships, but in music they forged their deepest bonds. A former violinist who spent a season with the San Antonio Symphony, Dan Wolfe raised his son to love all sorts of music. -

Inhalt / Contents

INHALT / CONTENTS African Flower (Petite Fleur Africaine) Butterfly Dolphin Dance Afro Blue Byrd Like Domino Biscuit Afternoon In Paris C'est Si Bon Don't Blame Me Água De Beber (Water To Drink) Call Me Don't Get Around Much Anymore Airegin Call Me Irresponsible Donna Lee Alfie Can't Help Lovin' Dat Man Dream A Little Dream Of Me Alice In Wonderland Captain Marvel Dreamsville All Blues Central Park West Easter Parade All By Myself Ceora Easy Living All Of Me Chega De Saudade (No More Blues) Easy To Love (You'd Be So Easy To All Of You Chelsea Bells Love) All The Things You Are Chelsea Bridge Ecclusiastics Alright, Okay, You Win Cherokee (Indian Love Song) Eighty One Always Cherry Pink And Apple Blossom El Gaucho Ana Maria White Epistrophy Angel Eyes A Child Is Born Equinox Anthropology Chippie Equipoise Apple Honey Chitlins Con Carne E.S.P. April In Paris Come Sunday Fall April Joy Como En Vietnam Falling Grace Arise, Her Eyes Con Alma Falling In Love With Love Armageddon Conception Fee-Fi-Fo-Fum Au Privave Confirmation A Fine Romance Autumn In New York Contemplation 500 Miles High Autumn Leaves Coral 502 Blues Beautiful Love Cotton Tail Follow Your Heart Beauty And The Beast Could It Be You Footprints Bessie's Blues Countdown For All We Know Bewitched Crescent For Heaven's Sake Big Nick Crystal Silence (I Love You) For Sentimental Reasons Black Coffee D Natural Blues Forest Flower Black Diamond Daahoud Four Black Narcissus Dancing On The Ceiling Four On Six Black Nile Darn That Dream Freddie Freeloader Black Orpheus Day Waves Freedom Jazz Dance Blue Bossa Days And Nights Waiting Full House Blue In Green Dear Old Stockholm Gee Baby, Ain't I Good To You Blue Monk Dearly Beloved Gemini The Blue Room Dedicated To You Giant Steps Blue Train (Blue Trane) Deluge The Girl From Ipanema (Garota De Blues For Alice Desafinado Ipanema) Bluesette Desert Air Gloria's Step Body And Soul Detour Ahead God Bless' The Child Boplicity (Be Bop Lives) Dexterity Golden Lady Bright Size Life Dizzy Atmosphere Good Evening Mr. -

Tommy Dorsey 1 9

Glenn Miller Archives TOMMY DORSEY 1 9 3 7 Prepared by: DENNIS M. SPRAGG CHRONOLOGY Part 1 - Chapter 3 Updated February 10, 2021 TABLE OF CONTENTS January 1937 ................................................................................................................. 3 February 1937 .............................................................................................................. 22 March 1937 .................................................................................................................. 34 April 1937 ..................................................................................................................... 53 May 1937 ...................................................................................................................... 68 June 1937 ..................................................................................................................... 85 July 1937 ...................................................................................................................... 95 August 1937 ............................................................................................................... 111 September 1937 ......................................................................................................... 122 October 1937 ............................................................................................................. 138 November 1937 ......................................................................................................... -

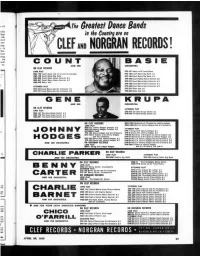

CLEF and NORGRAN RECORDS ’ Blic

ne Breitest Bence Bends ndly that In the Country ere on I ob- nted rec- ncy, 8 to CLEF AND NORGRAN RECORDS ’ blic. ■tion song Host ORCHESTRA ON CLEF RECORDS LONG PUT EPC-157 Dance with Count Basie MGC-120 Count Basle and his Orchestra Collates EPC IOS Count Basie Big Band sr 1 MGC-140 Count Basle Big Band EPC IM Count Basie Big Band sr 2 MGC «26 Count Basle Dance Session #1 EPC-220 Count Basle Dance Session # 1 MGC-G47 Count Basle Dance Session 02 EPC-221 Count Basie Dance Session #2 MGC-833 Basle la» EPC-338 Count Basie Dance Session #3 EXTENDED PUT EPC-338 Count Basle Dance Session #4 EPC-132 Count Basle and His Orchestra #1 EPC-251 Basie Jan #1 EPC-14? Count Basle and His Orchestra #2 EPC 252 Basie Jan #2 ORCHISfRA ON CLEF RECORDS EXTENBEB PUT LONG PUT EPC-247 The Gene Krupa Sextet # 1 MGC-147 The Gene Krupa Sextet #1 EPC-248 The Gene Krupa Sextet #2 MGC-152 The Gene Krupe Sextet #2 MGC 831 The Gene Krupa Sextet #3 ON CLEF RECOROS MGN-1004 Memorles ot Elllngton by Johnny Hodges LONS PUT MGN-10M More of Johnny Hodges end Hli Jrchestra MCC-111 Johnny Hodges Collates #1 MGC-12» Johnny Hodges Collates 02 EXTENOEB PUT EXTENDED PUT (PN-1 Swing with Johnny Hodges #1 EPC-12» Johnny Hodges «nd His Orchestra EPN-2 Swing with Johnny Hodges 02 (PC-148 Al Hibbler with johnny Hodges 6PN 28 Memorles ot Elllngton by Johnny Hodges #1 and His Orchestra (PN 27 Memorles of Elllngton by Johnny Hodges #2 EPC 183 Dance with Johnny Hodges #1 EPN-83 More iH Johnny Hodges end His Orchestra O1 EPC 164 Oance with Johnny Hodges #2 (PN-44 Mora of Johnny Hodges -

Trevor Tolley Jazz Recording Collection

TREVOR TOLLEY JAZZ RECORDING COLLECTION TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction to collection ii Note on organization of 78rpm records iii Listing of recordings Tolley Collection 10 inch 78 rpm records 1 Tolley Collection 10 inch 33 rpm records 43 Tolley Collection 12 inch 78 rpm records 50 Tolley Collection 12 inch 33rpm LP records 54 Tolley Collection 7 inch 45 and 33rpm records 107 Tolley Collection 16 inch Radio Transcriptions 118 Tolley Collection Jazz CDs 119 Tolley Collection Test Pressings 139 Tolley Collection Non-Jazz LPs 142 TREVOR TOLLEY JAZZ RECORDING COLLECTION Trevor Tolley was a former Carleton professor of English and Dean of the Faculty of Arts from 1969 to 1974. He was also a serious jazz enthusiast and collector. Tolley has graciously bequeathed his entire collection of jazz records to Carleton University for faculty and students to appreciate and enjoy. The recordings represent 75 years of collecting, spanning the earliest jazz recordings to albums released in the 1970s. Born in Birmingham, England in 1927, his love for jazz began at the age of fourteen and from the age of seventeen he was publishing in many leading periodicals on the subject, such as Discography, Pickup, Jazz Monthly, The IAJRC Journal and Canada’s popular jazz magazine Coda. As well as having written various books on British poetry, he has also written two books on jazz: Discographical Essays (2009) and Codas: To a Life with Jazz (2013). Tolley was also president of the Montreal Vintage Music Society which also included Jacques Emond, whose vinyl collection is also housed in the Audio-Visual Resource Centre. -

Grace Potter &The Nocturnals Launch

GRACE POTTER &THE NOCTURNALS LAUNCH VAULTURNAL: HIGH-QUALITY LIVE RECORDINGS FROM THE BAND’S VAST ARCHIVES FIRST RELEASE IS A COMPLETE HEADLINING SHOW RECORDED AT TANGLEWOOD (LOS ANGELES - Nov. 25, 2014) Critically acclaimed rock band and touring powerhouse Grace Potter & the Nocturnals have announced the launch of Vaulturnal. Vaulturnal will offer fans fully mixed and mastered soundboard recordings of live performances from the band’s ever-growing live archives. Initially, GPN plans to release several shows per year as high-quality digital downloads and on compact disc. “We’ve been talking for a long time about launching a live site for fans to access our music, and we have a fanbase that really does feed off the live-music experience,” Grace says of her band’s motivation for undertaking this ongoing project. GPN drummer and co-founder Matt Burr added, “We’re excited to handpick shows that we’re really passionate about and get them out there.” The flagship release, now available at http://www.vaulturnal.com, documents in full the band’s show at the Koussevitsky Music Shed in the famed Tanglewood Music Center in Lenox, MA, on the night of Aug. 19, 2013. The performance was “a barn-burner from start to finish,” according to Grace, comprising selections from each of the band’s albums, including spirited takes on fan favorites like “Medicine,” “Apologies,” “Stars,” “Paris (Ooh La La)”, and the 22-song set also features three covers — an acoustic interpretation of the Junior Parker-penned Elvis classic “Mystery Train”; Heart’s “Crazy On You,” a frequently performed crowd- pleaser during the tour; and a one-off work-up of Pink Floyd’s “Time,” which took shape spontaneously in the middle of show closer “The Lion The Beast The Beat.” As for future releases, the possibilities are endless, according to Grace. -

Notations Spring 2011

The ASCAP Foundation Making music grow since 1975 www.ascapfoundation.org Notations Spring 2011 Tony Bennett & Susan Benedetto Honored at ASCAP Foundation Awards The ASCAP Foundation held its 15th Annual Awards Ceremony at the Allen Room, Frederick P. Rose Hall, Home of Jazz at Lincoln Center, in New York City on December 8, 2010. Hosted by ASCAP Foundation President, Paul Williams, the event honored vocal legend Tony Bennett and his wife, Susan Benedetto, with The ASCAP Foundation Champion Award in recognition of their unique and significant efforts in arts education. ASCAP Foundation Champion Award recipients Susan Benedetto (l) & Tony Bennett with Mary Rodgers (2nd from left), Mary Ellin A wide variety of ASCAP Foundation Scholarship Barrett (2nd from right), and ASCAP Foundation President Paul and Award recipients were also honored at the Williams (r). event, which included special performances by some of the honorees. For more details and photos of the event, please see our website. Bart Howard provides a Musical Gift The ASCAP Foundation is pleased to announce that composer, lyricist, pianist and ASCAP member Bart Howard (1915-2004) named The ASCAP Foundation as a major beneficiary of all royalties and copyrights from his musical compositions. In line with this generous bequest, The ASCAP Foundation has established programs designed to ensure the preservation of Bart Howard’s name and legacy. These efforts include: Songwriters: The Next Generation, presented by The ASCAP Foundation and made possible by the Bart Howard Estate which showcases the work of emerging songwriters and composers who perform on the Kennedy Center’s Millennium Stage. The ASCAP Foundation Bart Howard Songwriting Scholarship at Berklee College recog- nizes talent, professionalism, musical ability and career potential in songwriting.