The Sound of Surprise 46 Pieces on Jazz.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Duke Ellington Kyle Etges Signature Recordings Cottontail

Duke Ellington Kyle Etges Signature Recordings Cottontail. Cottontail stands as a fine example of Ellington’s “Blanton-Webster” years, where the band was at its peak in performance and popularity. The “Blanton-Webster” moniker refers to bassist Jimmy Blanton and tenor saxophonist Ben Webster, who recorded Cottontail on May 4th, 1940 alongside Johnny Hodges, Barney Bigard, Chauncey Haughton, and Harry Carney on saxophone; Cootie Williams, Wallace Jones, and Ray Nance on trumpet; Rex Stewart on cornet; Juan Tizol, Joe Nanton, and Lawrence Brown on trombone; Fred Guy on guitar, Duke on piano, and Sonny Greer on drums. John Hasse, author of The Life and Genius of Duke Ellington, states that Cottontail “opened a window on the future, predicting elements to come in jazz.” Indeed, Jimmy Blanton’s driving quarter-note feel throughout the piece predicts a collective gravitation away from the traditional two feel amongst modern bassists. Webster’s solo on this record is so iconic that audiences would insist on note-for-note renditions of it in live performances. Even now, it stands as a testament to Webster’s mastery of expression, predicting techniques and patterns that John Coltrane would use decades later. Ellington also shows off his Harlem stride credentials in a quick solo before going into an orchestrated sax soli, one of the first of its kind. After a blaring shout chorus, the piece recalls the A section before Harry Carney caps everything off with the droning tonic. Diminuendo & Crescendo in Blue. This piece is remarkable for two reasons: Diminuendo & Crescendo in Blue exemplifies Duke’s classical influence, and his desire to write more grandiose pieces with more extended forms. -

ألبوù… (الألبوù…ات & الجØ

Lee Konitz ألبوم قائمة (الألبوم ات & الجدول الزمني) Jazz Nocturne https://ar.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/jazz-nocturne-30595290/songs Live at the Half Note https://ar.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/live-at-the-half-note-25096883/songs Lee Konitz with Warne Marsh https://ar.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/lee-konitz-with-warne-marsh-20813610/songs Lee Konitz Meets Jimmy Giuffre https://ar.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/lee-konitz-meets-jimmy-giuffre-3228897/songs Organic-Lee https://ar.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/organic-lee-30642878/songs https://ar.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/lee-konitz-meets-warne-marsh-again- Lee Konitz Meets Warne Marsh Again 28405627/songs Subconscious-Lee https://ar.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/subconscious-lee-7630954/songs https://ar.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/an-image%3A-lee-konitz-with-strings- An Image: Lee Konitz with Strings 24966652/songs Lee Konitz Plays with the Gerry https://ar.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/lee-konitz-plays-with-the-gerry-mulligan- Mulligan Quartet quartet-24078058/songs Anti-Heroes https://ar.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/anti-heroes-28452844/songs Alto Summit https://ar.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/alto-summit-28126595/songs Pyramid https://ar.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/pyramid-28452798/songs Live at Birdland https://ar.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/live-at-birdland-19978246/songs Oleo https://ar.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/oleo-28452776/songs Very Cool https://ar.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/very-cool-25096889/songs -

Gerry Mulligan Discography

GERRY MULLIGAN DISCOGRAPHY GERRY MULLIGAN RECORDINGS, CONCERTS AND WHEREABOUTS by Gérard Dugelay, France and Kenneth Hallqvist, Sweden January 2011 Gerry Mulligan DISCOGRAPHY - Recordings, Concerts and Whereabouts by Gérard Dugelay & Kenneth Hallqvist - page No. 1 PREFACE BY GERARD DUGELAY I fell in love when I was younger I was a young jazz fan, when I discovered the music of Gerry Mulligan through a birthday gift from my father. This album was “Gerry Mulligan & Astor Piazzolla”. But it was through “Song for Strayhorn” (Carnegie Hall concert CTI album) I fell in love with the music of Gerry Mulligan. My impressions were: “How great this man is to be able to compose so nicely!, to improvise so marvellously! and to give us such feelings!” Step by step my interest for the music increased I bought regularly his albums and I became crazy from the Concert Jazz Band LPs. Then I appreciated the pianoless Quartets with Bob Brookmeyer (The Pleyel Concerts, which are easily available in France) and with Chet Baker. Just married with Danielle, I spent some days of our honey moon at Antwerp (Belgium) and I had the chance to see the Gerry Mulligan Orchestra in concert. After the concert my wife said: “During some songs I had lost you, you were with the music of Gerry Mulligan!!!” During these 30 years of travel in the music of Jeru, I bought many bootleg albums. One was very important, because it gave me a new direction in my passion: the discographical part. This was the album “Gerry Mulligan – Vol. 2, Live in Stockholm, May 1957”. -

NILES HERALD-SPECTATOR SI.5() 'Fini Rsdav, Jui' 14, 2016 Nileslicraldspectatorconi

o NILES HERALD-SPECTATOR SI.5() 'Fini rsdav, Jui' 14, 2016 nileslicraldspectatorconi GO Carnival bringsoutcrowd St. John Brebeuf four-day event offers something for everyone.Page 6 (n PARAMOUNT PICTURES 'Titanic' live Chicago Symphony Orchestra to perform score to blockbuster film during screening at Ravinia Page23 SPORTS US ROWING So close KARIE ANGELI LUC/PIONEER PRESS Skokie native comes up short in quest to JosephMazurof NIlescallsbingo on July10at St.John Brebeuf Church in Niles. make U.S. Olympic Rowing team. Page 44 ;i;si i xhiIiii,i (hr.iiìj /t1JtiI 2t LOA 2 I Grill ILiI...e Duke! The Official John Wayne Way to Grill contains more than loo recipes, including some straight from the Wayne family archivesplus rare family and film photòs, personal anecdotes, heartwarming stories and an introduction by his son Ethan Wayne. Discover not only what GPEAT SYOPIES& MANLY MEALS SHAPEDBY DUKE'S America's most enduring FAMILY icon loved to eatbut also the essence of what made him a legend. Go to OrVewsstandsNow.corn Use the discount code Tribune at checkout to receive a special price of $16.99 plus S&H Available While Supplies Last L 3 4 Call for a complimentary consultation designer bolzhrooms Visit Our Bathroom Design Showroom 6919 N. Lincoln Ave, Lincoinwood, L' Open Monday- Friday: 10-5, Saturday: 10-4 Serving Cook, Lake, Dupage, Kane and Will Counties SHOUT OUT NILES HERALD-SPECTATOR nilesheraldspectator.com Eve Michelini, Glenview librarian Jim Rotche, General Manager Eve Michelini, 58, a Nues resident, started working at the reader services desk at the Glenview Phil Junk, Suburban Editor Public Library three months ago, and before that she John Puterbaugh, Pioneer Press Editor: worked at the Brown County Library in Green Bay, 312-222-2337; jputerbaugh®tribpuhcom Wis. -

How to Play in a Band with 2 Chordal Instruments

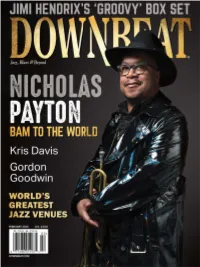

FEBRUARY 2020 VOLUME 87 / NUMBER 2 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Andy Hermann, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow; South Africa: Don Albert. -

88-Page Mega Version 2016 2015 2014 2013 2012 2011 2010

The Gift Guide YEAR-LONG, ALL OCCCASION GIFT IDEAS! 88-PAGE MEGA VERSION 2017 2016 2015 2014 2013 2012 2011 2010 COMBINED jazz & blues report jazz-blues.com The Gift Guide YEAR-LONG, ALL OCCCASION GIFT IDEAS! INDEX 2017 Gift Guide •••••• 3 2016 Gift Guide •••••• 9 2015 Gift Guide •••••• 25 2014 Gift Guide •••••• 44 2013 Gift Guide •••••• 54 2012 Gift Guide •••••• 60 2011 Gift Guide •••••• 68 2010 Gift Guide •••••• 83 jazz &blues report jazz & blues report jazz-blues.com 2017 Gift Guide While our annual Gift Guide appears every year at this time, the gift ideas covered are in no way just to be thought of as holiday gifts only. Obviously, these items would be a good gift idea for any occasion year-round, as well as a gift for yourself! We do not include many, if any at all, single CDs in the guide. Most everything contained will be multiple CD sets, DVDs, CD/DVD sets, books and the like. Of course, you can always look though our back issues to see what came out in 2017 (and prior years), but none of us would want to attempt to decide which CDs would be a fitting ad- dition to this guide. As with 2016, the year 2017 was a bit on the lean side as far as reviews go of box sets, books and DVDs - it appears tht the days of mass quantities of boxed sets are over - but we do have some to check out. These are in no particular order in terms of importance or release dates. -

Jazz Piano for Dancers & Listeners

JAZZ PIANO FOR DANCERS & LISTENERS The Bill Jackman Trio – Volume 2 of 6 1. Autumn Leaves (Latin, 10:15) by Joseph Kosma* 2. Satin Doll (swing, 10:18) by Duke Ellington, Billy Strayhorn, and Johnny Mercer 3. Polka Dots and Moonbeams (ballad, 10:25) by Jimmy Van Heusen 4. The Shadow of Your Smile (Latin, 9:20) by Johnny Mandel 5. Everything Happens to Me (ballad, 10:41) by Matt Dennis 6. All the Things You Are (swing, 8:46) by Jerome Kern 7. The Oakland Slow Blues (slow blues, 13.11) by Bill Jackman Total Playing Time: 72 minutes, 56 seconds * Only the composer(s) of the music are cited. About the Tunes 1. Autumn Leaves (Latin, 10:15) by Joseph Kosma (1947) “Autumn Leaves” has been part of classic American popular music for more than half a century. But it was originally a French song which quickly became an international hit after it was first sung by Yves Montand in a 1946 French film. However, its composer, Joseph Kosma, was not a native Frenchman. Rather he was a Hungarian Jew, who composed scores for Hungarian films in the late 1920s. With the rise of Nazism, he fled to France, where he worked as a café pianist and began a long association with the French poet Jacques Prevert and the French film director Jean Renoir. The latter left France for Hollywood during World War II. Kosma remained, but had to spend much of the time in hiding. “Autumn Leaves” was introduced as a slow ballad, but most jazz musicians have done it as a swing tune (e.g., Miles Davis) and often at a fast tempo. -

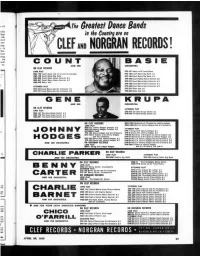

CLEF and NORGRAN RECORDS ’ Blic

ne Breitest Bence Bends ndly that In the Country ere on I ob- nted rec- ncy, 8 to CLEF AND NORGRAN RECORDS ’ blic. ■tion song Host ORCHESTRA ON CLEF RECORDS LONG PUT EPC-157 Dance with Count Basie MGC-120 Count Basle and his Orchestra Collates EPC IOS Count Basie Big Band sr 1 MGC-140 Count Basle Big Band EPC IM Count Basie Big Band sr 2 MGC «26 Count Basle Dance Session #1 EPC-220 Count Basle Dance Session # 1 MGC-G47 Count Basle Dance Session 02 EPC-221 Count Basie Dance Session #2 MGC-833 Basle la» EPC-338 Count Basie Dance Session #3 EXTENDED PUT EPC-338 Count Basle Dance Session #4 EPC-132 Count Basle and His Orchestra #1 EPC-251 Basie Jan #1 EPC-14? Count Basle and His Orchestra #2 EPC 252 Basie Jan #2 ORCHISfRA ON CLEF RECORDS EXTENBEB PUT LONG PUT EPC-247 The Gene Krupa Sextet # 1 MGC-147 The Gene Krupa Sextet #1 EPC-248 The Gene Krupa Sextet #2 MGC-152 The Gene Krupe Sextet #2 MGC 831 The Gene Krupa Sextet #3 ON CLEF RECOROS MGN-1004 Memorles ot Elllngton by Johnny Hodges LONS PUT MGN-10M More of Johnny Hodges end Hli Jrchestra MCC-111 Johnny Hodges Collates #1 MGC-12» Johnny Hodges Collates 02 EXTENOEB PUT EXTENDED PUT (PN-1 Swing with Johnny Hodges #1 EPC-12» Johnny Hodges «nd His Orchestra EPN-2 Swing with Johnny Hodges 02 (PC-148 Al Hibbler with johnny Hodges 6PN 28 Memorles ot Elllngton by Johnny Hodges #1 and His Orchestra (PN 27 Memorles of Elllngton by Johnny Hodges #2 EPC 183 Dance with Johnny Hodges #1 EPN-83 More iH Johnny Hodges end His Orchestra O1 EPC 164 Oance with Johnny Hodges #2 (PN-44 Mora of Johnny Hodges -

Jazz Standards Arranged for Classical Guitar in the Style of Art Tatum

JAZZ STANDARDS ARRANGED FOR CLASSICAL GUITAR IN THE STYLE OF ART TATUM by Stephen S. Brew Submitted to the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree, Doctor of Music Indiana University May 2018 Accepted by the faculty of the Indiana University Jacobs School of Music, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Music Doctoral Committee ______________________________________ Luke Gillespie, Research Director ______________________________________ Ernesto Bitetti, Chair ______________________________________ Andrew Mead ______________________________________ Elzbieta Szmyt February 20, 2018 ii Copyright © 2018 Stephen S. Brew iii To my wife, Rachel And my parents, Steve and Marge iv Acknowledgements This document would not have been possible without the guidance and mentorship of many creative, intelligent, and thoughtful musicians. Maestro Bitetti, your wisdom has given me the confidence and understanding to embrace this ambitious project. It would not have been possible without you. Dr. Strand, you are an incredible mentor who has made me a better teacher, performer, and person; thank you! Thank you to Luke Gillespie, Elzbieta Szmyt, and Andrew Mead for your support throughout my coursework at IU, and for serving on my research committee. Your insight has been invaluable. Thank you to Heather Perry and the staff at Stonehill College’s MacPhaidin Library for doggedly tracking down resources. Thank you James Piorkowski for your mentorship and encouragement, and Ken Meyer for challenging me to reach new heights. Your teaching and artistry inspire me daily. To my parents, Steve and Marge, I cannot express enough thanks for your love and support. And to my sisters, Lisa, Karen, Steph, and Amanda, thank you. -

Trevor Tolley Jazz Recording Collection

TREVOR TOLLEY JAZZ RECORDING COLLECTION TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction to collection ii Note on organization of 78rpm records iii Listing of recordings Tolley Collection 10 inch 78 rpm records 1 Tolley Collection 10 inch 33 rpm records 43 Tolley Collection 12 inch 78 rpm records 50 Tolley Collection 12 inch 33rpm LP records 54 Tolley Collection 7 inch 45 and 33rpm records 107 Tolley Collection 16 inch Radio Transcriptions 118 Tolley Collection Jazz CDs 119 Tolley Collection Test Pressings 139 Tolley Collection Non-Jazz LPs 142 TREVOR TOLLEY JAZZ RECORDING COLLECTION Trevor Tolley was a former Carleton professor of English and Dean of the Faculty of Arts from 1969 to 1974. He was also a serious jazz enthusiast and collector. Tolley has graciously bequeathed his entire collection of jazz records to Carleton University for faculty and students to appreciate and enjoy. The recordings represent 75 years of collecting, spanning the earliest jazz recordings to albums released in the 1970s. Born in Birmingham, England in 1927, his love for jazz began at the age of fourteen and from the age of seventeen he was publishing in many leading periodicals on the subject, such as Discography, Pickup, Jazz Monthly, The IAJRC Journal and Canada’s popular jazz magazine Coda. As well as having written various books on British poetry, he has also written two books on jazz: Discographical Essays (2009) and Codas: To a Life with Jazz (2013). Tolley was also president of the Montreal Vintage Music Society which also included Jacques Emond, whose vinyl collection is also housed in the Audio-Visual Resource Centre. -

The Recordings

Appendix: The Recordings These are the URLs of the original locations where I found the recordings used in this book. Those without a URL came from a cassette tape, LP or CD in my personal collection, or from now-defunct YouTube or Grooveshark web pages. I had many of the other recordings in my collection already, but searched for online sources to allow the reader to hear what I heard when writing the book. Naturally, these posted “videos” will disappear over time, although most of them then re- appear six months or a year later with a new URL. If you can’t find an alternate location, send me an e-mail and let me know. In the meantime, I have provided low-level mp3 files of the tracks that are not available or that I have modified in pitch or speed in private listening vaults where they can be heard. This way, the entire book can be verified by listening to the same re- cordings and works that I heard. For locations of these private sound vaults, please e-mail me and I will send you the links. They are not to be shared or downloaded, and the selections therein are only identified by their numbers from the complete list given below. Chapter I: 0001. Maple Leaf Rag (Joplin)/Scott Joplin, piano roll (1916) listen at: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9E5iehuiYdQ 0002. Charleston Rag (a.k.a. Echoes of Africa)(Blake)/Eubie Blake, piano (1969) listen at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=R7oQfRGUOnU 0003. Stars and Stripes Forever (John Philip Sousa, arr. -

Diego Rivera Bio 2020

DIEGO RIVERA SAXOPHONIST - COMPOSER - ARRANGER ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR OF JAZZ SAXOPHONE - MICHIGAN STATE UNIVERSITY “...his playing is carefully phrased and beautifully nuanced…” - Jazz Times A world-class musician, composer, arranger and educator, Diego Rivera has entertained audiences for over 20 years. Rivera is known for his muscular tone and unique blend of straight-ahead mainstream jazz fused with music inspired by his Latino background and heritage. He is a tenured Associate Professor of Jazz Saxophone at Michigan State University where he also serves as Associate Director of Jazz Studies. Rivera was born in Ann Arbor, MI and raised ‘just up the road’ in East Lansing, MI. Born into a Mexican- American family, his Chicano heritage has always been important to him and shaped his creative endeavors. His parents named him after the famed muralist, Diego Rivera. A trip to the Detroit Institute of Arts at a young age inspired him to make his own mark with the Saxophone rather than the brush. He attended Michigan State University where he studied with Andrew Speight, Branford Marsalis, Ron Blake and Rodney Whitaker. In 1999, he began his professional and touring career with the Jimmy Dorsey Orchestra on their Big Band ‘99 tour. Since that maiden voyage, he has performed concerts at the most prestigious venues and festivals across the United States, Canada, Europe and Asia. He currently leads his own group, The Diego Rivera Quartet. Rivera has also toured with GRAMMY-Award winning vocalist, Kurt Elling, JUNO-Award winning Canadian Jazz Vocalist, Sophie Milman and The Rodney Whitaker Quintet. He is a member of the The Ulysses Owens Jr.