Peter Lewis - the Rebel Hangs Ten in Hollywood

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Conversation with Brother Michael About Janis Joplin's Personality, His

Friday, March 4th Briquettes Smokehouse 2SHQ0LF By Helen Marketti Sunday, March 6th Old Mill Winery A conversation with Brother Michael about Janis 2SHQ0LF¬ Joplin’s personality, his memories, and the upcoming 7KXUVGD\0DUFKWK 12-YEAR ANNIVERSARY! Dublin Downs show - A Night with Janis Joplin 6W3DW·V¬² Friday, March 11th Come celebrate St. Patrick’s Day with On March 2, A Cebars in Madison us in a real Irish Pub!!! Night with Janis Joplin will be taking 8:30 - 11:00 place at The Connor Table reservations require that the Palace at Playhouse party orders dinner but there will be Square. Cleveland’s bar seats and standing room. own Mary Bridget (440) 428-9926 Davies will be playing the role of Janis. A rock icon of Saturday, April 23rd the late 60s and early 70s, Janis Joplin’s Hooley House in Mentor name is synonymous with a counter Check out the Abbey Rodeo video at: culture generation www.youtube.com/watch?v=siwWk_2hELk Cat seeking change and establishing one’s own identity. Her heart pounding lyrics to Piece of My Heart, Me and Bobby www.Abbeyrodeo.com Lilly McGee, Mercedes Benz, Ball and Chain, Cry Baby and many more still hold the attention of music fans who remember her and new ones who are discovering the blues and rock singer. Janis Joplin’s brother, Michael took a few moments recently to talk about the show, his famous sister and her musical infl uence. Michael gives us a glimpse into his life while growing up. “My father was classical music oriented. My mom was too but she liked Broadway musicals such as Threepenny Opera and West Side Story,” he remembers. -

The Caravan Playlist 147 Friday, March 18, 2016 Hour 1 Artist Track

The Caravan Playlist 147 Friday, March 18, 2016 Hour 1 Artist Track CD/Source Label Andrew Bird Natural Disaster Noble Beast Fat Possum - c 2009 Lamb Chop I Can Hardly Spell My Name Is A Woman Merge Records - c 2002 David Darling Solitude Cello Blue Hearts of Space - c 2001 Caroline Fenn Monsters Fragile Chances ECR Music Group - c 2012 Erin Mckeown Easy Baby Monday Morning Cold TVP Records - c 1997 Buddy Flett I Got Evil (Don't You Lie To Me) Mississippi Sea Out Of The Past - c 2007 Moby Grape Never Grape Jam Sundazed Music - c 2007 Janis Joplin Ball and Chain Monterey Pop Festival 1967 Rhino - c 1997 Steppenwolf Monster Live Steppenwolf MCA - c 1971 Mammas and Pappas California Dreamin' Monterey Pop Festival 1967 Rhino - c 1997 Janis Joplin Try Woodstock Anniversary Collection Atlantic - c 1994 Hour 2 Artist Track Concert Source Choir Of Young Believers NYE no TRE Guitar Showroom at SXSW NPR Music - c 2010 Choir Of Young Believers These Rituals of Mine Guitar Showroom at SXSW NPR Music - c 2010 Choir Of Young Believers Action/Reaction Guitar Showroom at SXSW NPR Music - c 2010 Choir Of Young Believers NYE no ET Guitar Showroom at SXSW NPR Music - c 2010 Choir Of Young Believers Why Must it Always Be This Way Guitar Showroom at SXSW NPR Music - c 2010 Choir Of Young Believers Hollow Talk Guitar Showroom at SXSW NPR Music - c 2010 Yeah Yeah Yeahs Under The Earth NPR Music's SXSW at Stubbs NPR Music - c 2013 Yeah Yeah Yeahs Gold Lion NPR Music's SXSW at Stubbs NPR Music - c 2013 Yeah Yeah Yeahs Subway NPR Music's SXSW at Stubbs NPR Music -

MUSIC 351: Psychedelic Rock of the 1960S Spring 2015, T 7:00–9:40 P.M., ENS-280

MUSIC 351: Psychedelic Rock of the 1960s Spring 2015, T 7:00–9:40 p.m., ENS-280 Instructor: Eric Smigel ([email protected]) M-235, office hours: Mondays & Tuesdays, 3:00–4:00 p.m. This is a lecture class that surveys psychedelic rock music and culture of the 1960s. Psychedelic music played an important role in the development of rock music as a predominant art form during one of the most formative decades in American history. Emerging along with the powerful counterculture of hippies in the mid-1960s, psychedelic rock reflects key elements of the “Love Generation,” including the peace movement, the sexual revolution, the pervasive use of recreational drugs (especially marijuana and LSD), and the growing awareness of Eastern philosophy. The main centers of countercultural activity—the Haight-Ashbury district of San Francisco and the London Underground—drew a high volume of media exposure, resulting in the famous “Summer of Love” and culminating in popular music festivals in Monterey, Woodstock, and Altamont. Students in this course will examine the music and lyrics of a selection of representative songs by The Grateful Dead, The Jefferson Airplane, Big Brother and the Holding Company, The Beatles, Pink Floyd, The Jimi Hendrix Experience, and other bands closely associated with the burgeoning psychedelic scene. Students will also consult primary source material—including interviews with several of the musicians, influential literature of the period, and essays by key figures of the movement—in order to gain insight into the social, political, -

Music Globally Protected Marks List (GPML) Music Brands & Music Artists

Music Globally Protected Marks List (GPML) Music Brands & Music Artists © 2012 - DotMusic Limited (.MUSIC™). All Rights Reserved. DotMusic reserves the right to modify this Document .This Document cannot be distributed, modified or reproduced in whole or in part without the prior expressed permission of DotMusic. 1 Disclaimer: This GPML Document is subject to change. Only artists exceeding 1 million units in sales of global digital and physical units are eligible for inclusion in the GPML. Brands are eligible if they are globally-recognized and have been mentioned in established music trade publications. Please provide DotMusic with evidence that such criteria is met at [email protected] if you would like your artist name of brand name to be included in the DotMusic GPML. GLOBALLY PROTECTED MARKS LIST (GPML) - MUSIC ARTISTS DOTMUSIC (.MUSIC) ? and the Mysterians 10 Years 10,000 Maniacs © 2012 - DotMusic Limited (.MUSIC™). All Rights Reserved. DotMusic reserves the right to modify this Document .This Document 10cc can not be distributed, modified or reproduced in whole or in part 12 Stones without the prior expressed permission of DotMusic. Visit 13th Floor Elevators www.music.us 1910 Fruitgum Co. 2 Unlimited Disclaimer: This GPML Document is subject to change. Only artists exceeding 1 million units in sales of global digital and physical units are eligible for inclusion in the GPML. 3 Doors Down Brands are eligible if they are globally-recognized and have been mentioned in 30 Seconds to Mars established music trade publications. Please -

Juice Newton Fan Club Spring Newsletter 2013 Birthday Wishes!!

Juice Newton Fan Club Spring Newsletter 2013 Hello everyone and Happy Spring!! We certainly hope you all have enjoyed your holidays and the new year thus far. The JNFC has grown with more members. I certainly and delighted that the club is solid and strong and that the members are so devoted to Juice and her music. (Thanks to Cindy Lane Adams for the photo of Juice) Birthday Wishes!! Thank you to everyone who wished Juice “Happy Birthday” on her special day! Please know that Juice sincerely appreciates everybody for remembering her. I too, wish to thank everyone for remembering me on my birthday this past March. Some of the communications that were sent in are so inspiring and rewarding. I want to shine the light on a JNFC member Geremar Donato who is a special member of the JNFC. He writes… “ Hi Paul! I just want to wish you a Happy Birthday! I hope you have everything you wished for. I want to thank you again for doing a great job on the Juice Newton fan club. All the fans are so lucky to have you. You care so much for us and you always do what it takes to make it the best. Keep up the good work. A good person like you deserves the very best. I've been a fan of Juice Newton for over 30 years. Yeah, I will always be her fan forever!” Geremar Once again, thank you Geremar and thank you all for your unwavering support of not only Juice, but also the JNFC!! 1 New Songs!! The wait is over for new material from Juice!! Juice is one of the many talents featured on the new duets album of Carla Olson! Carla Olson's new duets album "Have Harmony, Will Travel" will be released in April 28, 2013!! The tracks of the album consist of: From the 'Have Harmony, Will Travel' recording sessions: L-R: James Intveld, Juice Newton, Tom Fillman, Carla Olson and Tony Marsico. -

Title Format Released Abyssinians, the Satta Dub CD 1998 Acklin

Title Format Released Abyssinians, The Satta Dub CD 1998 Acklin, Barbara The Brunswick Anthology (Disc 2) CD 2002 The Brunswick Anthology (Disc 1) CD 2002 Adams Johnny Johnny Adams Sings Doc Pomus: The Real Me CD 1991 Adams, Johnny I Won't Cry CD 1991 Walking On A Tightrope - The Songs Of Percy Mayfield CD 1989 Good Morning Heartache CD 1993 Ade & His African Beats, King Sunny Juju Music CD 1982 Ade, King Sunny Odu CD 1998 Alabama Feels So Right CD 1981 Alexander, Arthur Lonely Just Like Me CD 1993 Allison, DeAnn Tumbleweed CD 2000 Allman Brothers Band, The Beginnings CD 1971 American Song-poem Anthology, The Do You Know The Difference Between Big Wood And Brush CD 2003 Animals, The Animals - Greatest Hits CD 1983 The E.P. Collection CD 1964 Aorta Aorta CD 1968 Astronauts, The Down The Line/ Travelin' Man CD 1997 Competition Coupe/Astronauts Orbit Kampus CD 1997 Rarities CD 1991 Go Go Go /For You From Us CD 1997 Surfin' With The Astronauts/Everything Is A-OK! CD 1997 Austin Lounge Lizards Paint Me on Velvet CD 1993 Average White Band Face To Face - Live CD 1997 Page 1 of 45 Title Format Released Badalamenti, Angelo Blue Velvet CD 1986 Twin Peaks - Fire Walk With Me CD 1992 Badfinger Day After Day [Live] CD 1990 The Very Best Of Badfinger CD 2000 Baker, Lavern Sings Bessie Smith CD 1988 Ball, Angela Strehli & Lou Ann Barton, Marcia Dreams Come True CD 1990 Ballard, Hank Sexy Ways: The Best of Hank Ballard & The Midnighters CD 1993 Band, The The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down: The Best Of The Band [Live] CD 1992 Rock Of Ages [Disc 1] CD 1990 Music From Big Pink CD 1968 The Band CD 1969 The Last Waltz [Disc 2] CD 1978 The Last Waltz [Disc 1] CD 1978 Rock Of Ages [Disc 2] CD 1990 Barker, Danny Save The Bones CD 1988 Barton, Lou Ann Read My Lips CD 1989 Baugh, Phil 64/65 Live Wire! CD 1965 Beach Boys, The Today! / Summer Days (And Summer Nights!!) CD 1990 Concert/Live In London [Bonus Track] [Live] CD 1990 Pet Sounds [Bonus Tracks] CD 1990 Merry Christmas From The Beach Boys CD 2000 Beatles, The Past Masters, Vol. -

Rock & Roll's War Against

Rock & Roll’s War Against God Copyright 2015 by David W. Cloud ISBN 978-1-58318-183-6 Tis book is published for free distribution in eBook format. It is available in PDF, Mobi (for Kindle, etc.) and ePub formats from the Way of Life web site. See the Free eBook tab at www.wayofife.org. We do not allow distribution of our free books from other web sites. Published by Way of Life Literature PO Box 610368, Port Huron, MI 48061 866-295-4143 (toll free) - [email protected] www.wayofife.org Canada: Bethel Baptist Church 4212 Campbell St. N., London Ont. N6P 1A6 519-652-2619 Printed in Canada by Bethel Baptist Print Ministry ii Table of Contents Introduction ...........................................................................1 What Christians Should Know about Rock Music ...........5 What Rock Did For Me ......................................................38 Te History of Rock Music ................................................49 How Rock & Roll Took over Western Society ...............123 1950s Rock .........................................................................140 1960s Rock: Continuing the Revolution ........................193 Te Character of Rock & Roll .........................................347 Te Rhythm of Rock Music .............................................381 Rock Musicians as Mediums ...........................................387 Rock Music and Voodoo ..................................................394 Rock Music and Insanity ..................................................407 Rock Music and Suicide ...................................................429 -

Oldiemarkt Magazin

EUR 7,10 DIE WELTWEIT GRÖSSTE MONATLICHE 01/08 VINYL -/ CD-AUKTION Januar Tommy James & The Shondells: Bubblegum? Poprock! Powered and designed by Peter Trieb – D 84453 Mühldorf Ergebnisse der AUKTION 350 Hier finden Sie ein interessantes Gebot dieser Auktion sowie die Auktionsergebnisse Anzahl der Gebote 2.518 Gesamtwert aller Gebote 40.341,00 Gesamtwert der versteigerten Platten / CD’s 21.873,00 Höchstgebot auf eine Platte / CD 710,00 Highlight des Monats Dezember 2007 2LP - Spectrum - Milesago - Harvest SHDW 50/51 - AU - M- / M- So wurde auf die Platte / CD auf Seite 19, Zeile 12 geboten: Mindestgebot EURO 18,00 Progressiver Rock aus Australien gehört Bieter 1 - 3 18,11 - 19,50 zu den begehrtesten Untergruppen des progressiven Rock allgemein. Bieter 4 - 5 20,99 - 21,13 Bands vom 5. Kontinent wie Buffalo, La - Bieter 6 8 23,73 - 25,00 De Das, Kahvas Jute oder Missing Links - erzielen seit langem sehr hohe Preise. In dieses Gebiet passt auch Spectrum aus Bieter 9 - 10 31,01 - 31,50 Australien. Bieter 11 - 12 45,11 - 48,80 Wie man sehen kann, ist das Mindestgebot für dieses Doppel-Album sehr zurückhaltend angesetzt, zumal die Qualität sehr ansprechend ist. Deswegen ist es kein Wunder, dass das Höchstgebot weit darüber liegt. Am überraschendsten ist die hohe Zahl der Bieter, die die eingangs geäußerte Behauptung unterstreicht. Bieter 13 51,80 Sie finden Highlight des Monats ab Juni 1998 im Internet unter www.plattensammeln.de Werden Sie reich durch OLDIE-MARKT – die Auktionszahlen sprechen für sich ! Software und Preiskataloge für Musiksammler bei Peter Trieb – D84442 Mühldorf – Fax (+49) 08631 – 162786 – eMail [email protected] Kleinanzeigenformulare WORD und EXCEL im Internet unter www.plattensammeln.de Schallplattenbörsen Oldie-Markt 1/08 3 Plattenbörsen 2007/8 Schallplattenbörsen sind seit einigen Jahren fester Bestandteil der europäischen Musikszene. -

Watly (Lamjma VOL

. ill lilt nthi ' . • r I , watly (Lamjma VOL. LXVII NO. 8 Serving Storrs Since 1896 OCTOBER I. 1969 Faculty Senate Approves Bill 'Adequate ' C ause Must for Dismissal See S tory On Page 6 Reopening ROTC Issue SDS Asks Mass Rally Oct. 15th UConn's Students for a Democratic Society pro- posed at their Monday meeting a mass rally In con- Junction with the Oct. 15 strike against the war In Vietnam. The meeting also resulted In a proposal for a demonstration focusing on the presence of the Reserve Officer Training Corps on campus. I SimpleSi But Creative 'Moby Grape9 Grows on You The Campus' Record Reviewer finds a new album by the 'Moby Grape" to be simple and creative. He warns that the listener has to give ■Truly Fine Citizen" a chance to "settle,* however. AEPi Bomb Cannister Examined by Expert A warrant for "misconduct with a motor vehi- cle" was issued yesterday to Lewis W. Gold, Jr., a UConn student who received a cerebral concus- sion in a two-car crash that killed a student here Sept. 21. He was released without bond. LETTERS TO THE EDITOR Qtatutttttrist Battg (Eampiw The Times They Are A-changin' Serving Storrs Since 1896 To the Editor: I happened to come across this arti- Dad. Under your system, privation in- cle the other day which 1 thought might creases in proportion to the increase OCTOBER 1, 1969 be of interest to some people. It was of production.'" written by a student editor at Kent State "Hold fast to the religion of you fa- University, Ohio, to his father: thers," you warn, and I cannot help wondering, "His that religion lessened "D»ar Dad, hatred, crime, war, and suffering In The last time I was home you said its Twentieth Century trial? Are its some significant things about my interest- fundamental concepts philosophically ing radical proposals for a new social sound?" order. -

Santa Fe "About 4 Years Old," Sirhan Said

VOL. Ill, No. 95 Over 3000 present as McCarthy accepts award by Bob Scheuler hold that ·there is more intelligence on Last night, United States Senator campus than in the country as a whole, l·:ugene J. McCarthy was presented the on the average. It follows tlwt change first annual Notre Dame Senior Class should he the most orderly and come Fellow A ward. Senator McCarthy spoke about best on the campuses." before three thousand people in Stepan lie then turned to the draft saying, "In Center as part of the 120th Annual the draft. .. people have to make moral Washington Day 1-:xerdses. decisions every day on life ami the war in McCarthy's speech was entertaining Vietnam. This is not surprising since the and spiced with many humorous United Stales made moral decisions on comments. The St·nator co!liiiH.!nted on Germany after World War II at I he the general mood of America today and Nurcmhurg Trials." touched on some of his experiences that Senator McCarthy concluded hy John Mroz PhU McKenna reflect this mood. admonishing students to guide their lives with integrity, decency and especially willingness. "A willingness to take risks Poll shows 2-way race with your life, your person, your reputation." by Glen Corso 3.5% of the total vote, as opposed to Senator M~.-·Carthy's speech at Stepan The first campus wide straw poll, taken McKenna's .2%. Center culminated his busy, two-day stay by the 0/JSI:R Vh"R, shows a fairly tight The actual vote was taken by choosing at Notre Dame. -

Songs in the Key of Z

covers complete.qxd 7/15/08 9:02 AM Page 1 MUSIC The first book ever about a mutant strain ofZ Songs in theKey of twisted pop that’s so wrong, it’s right! “Iconoclast/upstart Irwin Chusid has written a meticulously researched and passionate cry shedding long-overdue light upon some of the guiltiest musical innocents of the twentieth century. An indispensable classic that defines the indefinable.” –John Zorn “Chusid takes us through the musical looking glass to the other side of the bizarro universe, where pop spelled back- wards is . pop? A fascinating collection of wilder cards and beyond-avant talents.” –Lenny Kaye Irwin Chusid “This book is filled with memorable characters and their preposterous-but-true stories. As a musicologist, essayist, and humorist, Irwin Chusid gives good value for your enter- tainment dollar.” –Marshall Crenshaw Outsider musicians can be the product of damaged DNA, alien abduction, drug fry, demonic possession, or simply sheer obliviousness. But, believe it or not, they’re worth listening to, often outmatching all contenders for inventiveness and originality. This book profiles dozens of outsider musicians, both prominent and obscure, and presents their strange life stories along with photographs, interviews, cartoons, and discographies. Irwin Chusid is a record producer, radio personality, journalist, and music historian. He hosts the Incorrect Music Hour on WFMU; he has produced dozens of records and concerts; and he has written for The New York Times, Pulse, New York Press, and many other publications. $18.95 (CAN $20.95) ISBN 978-1-55652-372-4 51895 9 781556 523724 SONGS IN THE KEY OF Z Songs in the Key of Z THE CURIOUS UNIVERSE OF O U T S I D E R MUSIC ¥ Irwin Chusid Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Chusid, Irwin. -

P. 001-003 Front Matter

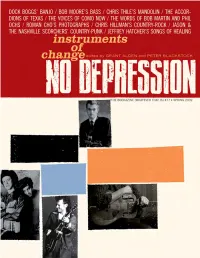

slate ○○○○○○○○○ DOCK BOGGS’ BANJO ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ 4 by Jesse Fox Mayshark ○○○○○○○○○○ THE VOICES OF COMO NOW ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ 14 by David Menconi ○○○○○○○○○○○○ THE ACCORDIONS OF TEXAS ○○○○○○○○○○○ 20 by Joe Nick Patoski ○○○○○○○○○ BOB MOORE’S BASS ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ 36 by Rich Kienzle ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ THE WORDS OF BOB MARTIN ○○○○○ 48 by Bill Friskics-Warren ROMAN CHO’S PHOTOGRAPHS ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○54 live, from McCabe’s Guitar Shop ○○○○○○○ CHRIS THILE’S MANDOLIN ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ 68 by Seth Mnookin ○○○○○○○○○○○ CHRIS HILLMAN’S COUNTRY-ROCK ○○○○○○○○○ 84 by Barry Mazor ○○○○○ JASON & THE NASHVILLE SCORCHERS’ COUNTRY-PUNK ○○○○○○○ 96 by Don McLeese ○○○○○○○ JEFFREY HATCHER’S SONGS OF HEALING ○○○○○○○○○○○ 110 by Lloyd Sachs ○○○○○○○○ THE WORDS OF PHIL OCHS ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ 128 by Kenneth J. Bernstein ○○○○○○○○ APPENDIX: REVIEWS ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ 136 Buddy & Julie Miller; Neko Case; Madeleine Peyroux; David Byrne & Brian Eno; Bruce Robison; A Tribute to Doug Sahm. COVER DESIGN BY JESSE MARINOFF REYES in homage to Reid Miles, repurposing photographs by Paul Cantin, John Carrico, Roman Cho, along with several uncredited promotional images INTERIOR PAGES DESIGNED BY GRANT ALDEN Copyright © 2009 by No Depression All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America First edition, 2009 Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to: Permissions University of Texas Press P.O. Box 7819 Austin, TX 78713-7819 www.utexas.edu/utpress/about/bpermission.html The paper used in this book meets the minimum requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (R1997) (Permanence of Paper). ISBN 978-0-292-71929-3 Library of Congress Control Number: 2008931429 This volume has been printed from camera-ready copy furnished by the author, who assumes full responsibility for its contents. the bookazine (whatever that is) #77 • spring 2009 Back when we were a bimonthly magazine, articles mostly were assigned around the release date of record albums.