Metamorphosis Volume 1(18 ) 1-16 Jan 1987.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

412 Genus Zophopetes Mabille

14th edition (2015). Genus Zophopetes Mabille, 1904 In Mabille, 1903-4. In: Wytsman, P.A.G., Genera Insectorum 17: 183 (210 pp.). Type-species: Pamphila dysmephila Trimen, by subsequent designation (Lindsey, 1925. Annals of the Entomological Society of America 18: 106 (75-106).). The palm nightfighters are an Afrotropical genus of six species. The antennae have prominent white clubs and the members of the genus are crepuscular (Larsen, 1991c). The larval foodplants are palms (Arecaceae) (Larsen, 1991c). *Zophopetes cerymica (Hewitson, 1867) Common Palm Nightfighter Hesperia cerymica Hewitson, 1867 in Hewitson, 1867-71. Illustrations of new species of exotic butterflies 4: 108 (118 pp.). Zophopetes cerymica cerymica (Hewitson, 1867). Evans, 1937. Zophopetes cerymica (Hewitson, 1867). Lindsey & Miller, 1965. Zophopetes cerymica. Male. Left – upperside; right – underside. Wingspan: 43mm. Ex pupa, Luanda, Angola. Em 9-11-73. I. Bampton. (Henning collection – H52). Type locality: Nigeria: “Old Calabar”. Distribution: Senegal, Gambia, Guinea-Bissau, Guinea, Sierra Leone, Liberia, Ivory Coast, Ghana, Togo, Benin, Nigeria, Cameroon, Gabon, Angola, Democratic Republic of Congo (east), Zambia (north-west). Specific localities: Ghana – Aburi (Ploetz, 1886); Bobiri Butterfly Sanctuary (Larsen et al., 2007); Boabeng-Fiema Monkey Sanctuary (Larsen et al., 2009). Nigeria – Old Calabar (TL). Gabon – Waka (van de Weghe, 2010). Uganda – Semuliki N.P. (Davenport & Howard, 1996). Kenya – Kilifi (Larsen, 1991c); Mombasa (Larsen, 1991c); Diani Beach (Larsen, 1991c). Tanzania – Gombe Stream (Kielland, 1990d); Mihumu Forest (Kielland, 1990d); Kasye Forest (Kielland, 1990d); Das es Salaam (Kielland, 1990d); Pugu Hills (Kielland, 1990d). Angola – Luanda (Bampton; male illustrated above). Zambia – Ikelenge (Heath et al., 2002). 1 Habitat: Varying habitats, as long as palms are present. -

NABRO Ecological Analysts CC Natural Asset and Botanical Resource Ordinations Environmental Consultants & Wildlife Specialists

NABRO Ecological Analysts CC Natural Asset and Botanical Resource Ordinations Environmental Consultants & Wildlife Specialists ENVIRONMENTAL BASELINE REPORT FOR HANS HOHEISEN WILDLIFE RESEARCH STATION Compiled by Ben Orban, PriSciNat. June 2013 NABRO Ecological Analysts CC. - Reg No: 16549023 / PO Box 11644, Hatfield, Pretoria. Our reference: NABRO / HHWRS/V01 NABRO Ecological Analysts CC Natural Asset and Botanical Resource Ordinations Environmental Consultants & Wildlife Specialists CONTENTS 1 SPECIALIST INVESTIGATORS ............................................................................... 3 2 DECLARATION ............................................................................................................ 3 3 INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................... 3 4 LOCALITY OF STUDY AREA .................................................................................... 4 4.1 Location ................................................................................................................... 4 5 INFRASTRUCTURE ..................................................................................................... 4 5.1 Fencing ..................................................................................................................... 4 5.2 Camps ...................................................................................................................... 4 5.3 Buildings ................................................................................................................ -

Arthropod Communities in Urban Agricultural Production Systems Under Different Irrigation Sources in the Northern Region of Ghana

insects Article Arthropod Communities in Urban Agricultural Production Systems under Different Irrigation Sources in the Northern Region of Ghana Louis Amprako 1, Kathrin Stenchly 1,2,3 , Martin Wiehle 1,4,5,* , George Nyarko 6 and Andreas Buerkert 1 1 Organic Plant Production and Agroecosystems Research in the Tropics and Subtropics (OPATS), University of Kassel, Steinstrasse 19, D-37213 Witzenhausen, Germany; [email protected] (L.A.); [email protected] (K.S.); [email protected] (A.B.) 2 Competence Centre for Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation (CliMA), University of Kassel, Kurt-Schumacher-Straße 25, D-34117 Kassel, Germany 3 Grassland Science and Renewable Plant Resources (GNR), University of Kassel, Steinstrasse 19, D-37213 Witzenhausen, Germany 4 Tropenzentrum-Centre for International Rural Development, University of Kassel, Steinstrasse 19, D-37213 Witzenhausen, Germany 5 International Center for Development and Decent Work, University of Kassel, Kleine Rosenstrasse 1-3, D-34109 Kassel, Germany 6 Department of Horticulture, Faculty of Agriculture, University for Development Studies (UDS), P.O. Box TL 1882, Tamale, Ghana; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 31 May 2020; Accepted: 27 July 2020; Published: 1 August 2020 Abstract: Urban and peri-urban agricultural (UPA) production systems in West African countries do not only mitigate food and financial insecurity, they may also foster biodiversity of arthropods and partly compensate for structural losses of natural environments. However, management practices in UPA systems like irrigation may also contribute to disturbances in arthropod ecology. To fill knowledge gaps in the relationships between UPA management and arthropod populations, we compared arthropods species across different irrigation sources in Tamale. -

088 Genus Zophopetes Mabille

AFROTROPICAL BUTTERFLIES. MARK C. WILLIAMS. http://www.lepsocafrica.org/?p=publications&s=atb Updated 10 March 2021 Genus Zophopetes Mabille, [1904] Palm Night-fighters In Mabille, [1903-4]. In: Wytsman, P.A.G., Genera Insectorum 17: 183 (210 pp.). Type-species: Pamphila dysmephila Trimen, by subsequent designation (Lindsey, 1925. Annals of the Entomological Society of America 18: 106 (75-106).). The genus Zophopetes belongs to the Family Hesperiidae Latreille, 1809; Subfamily Hesperiinae Latreille, 1809, Tribe Hesperiini Latreille, 1809. Other genera in the Tribe Hesperiini, are Lepella, Prosopalpus, Kedestes, Fulda, Gorgyra, Gyrogra, Teniorhinus, Flandria, Hollandus, Xanthodisca, Acada, Rhabdomantis, Osmodes, Parosmodes, Osphantes, Acleros, Paracleros, Semalea, Hypoleucis, Paronymus, Andronymus, Malaza, Perrotia, Ploetzia, Moltena, Chondrolepis, Tsitana, Gamia, Artitropa, Mopala, Pteroteinon, Leona, Caenides, Monza, Melphina, Melphinyet, Noctulana, Fresna, and Platylesches. Zophopetes (Palm Night-fighters) is an Afrotropical genus of seven species. The antennae have prominent white clubs and adults of the genus are crepuscular (Larsen, 1991c). The larval host-plants are palms (Arecaceae) (Larsen, 1991c). *Zophopetes barteni De Jong, 2017 Ebogo Palm Night-fighter Zophopetes barteni De Jong, 2017. Metamorphosis 28: 12 (11-15). Type locality: Cameroon: Ebogo (about 80 km, as the crow flies, south of Yaoundé), 40 21'00''N, 110 25'00''E, 600 m, 25–26 December 2012, leg. Frans Barten. Holotype (male) in collection of the Naturalis Biodiversity Centre, Leiden, The Netherlands, RMNH INS 910268. No further specimens are known. Etymology: Named for Frans Barten, the person who first collected it. Distribution: Cameroon. Specific localities: Cameroon – Egogo (TL; one male). Habitat: Partly degraded forest (De Jong, 2017). Habits: Nothing published. -

High Value Plant (HVPS) Phoenix Reclinata.Pdf

This report was generated from the SEPASAL database ( www.kew.org/ceb/sepasal ) in August 2007. This database is freely available to members of the public. SEPASAL is a database and enquiry service about useful "wild" and semi-domesticated plants of tropical and subtropical drylands, developed and maintained at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. "Useful" includes plants which humans eat, use as medicine, feed to animals, make things from, use as fuel, and many other uses. Since 2004, there has been a Namibian SEPASAL team, based at the National Botanical Research Institute of the Ministry of Agriculture which has been updating the information on Namibian species from Namibian and southern African literature and unpublished sources. By August 2007, over 700 Namibian species had been updated. Work on updating species information, and adding new species to the database, is ongoing. It may be worth visiting the web site and querying the database to obtain the latest information for this species. Internet SEPASAL New query Edit query View query results Display help In names list include: synonyms vernacular names and display: All names per page Your query found 1 taxon Phoenix reclinata Jacq. [ 1362 ] Family: PALMAE Synonyms Phoenix pumila Regel Phoenix senegalensis Van Houtte ex Salomon Phoenix spinosa Schum. & Thonn. Vernacular names Unspecified language Makindu palm (Mozambique) quinzo [ 316 ], sundo [ 316 ], inchece [ 316 ], iguindo [ 316 ], guindo [ 316 ] [ 5480 ], mitchinzo [316 ], mutchindo [ 316 ], muchindo [ 316 ], inchido [ 316 ], tcheu -

Insects on Palms

Insects on Palms i Insects on Palms F.W. Howard, D. Moore, R.M. Giblin-Davis and R.G. Abad CABI Publishing CABI Publishing is a division of CAB International CABI Publishing CABI Publishing CAB International 10 E 40th Street Wallingford Suite 3203 Oxon OX10 8DE New York, NY 10016 UK USA Tel: +44 (0)1491 832111 Tel: +1 (212) 481 7018 Fax: +44 (0)1491 833508 Fax: +1 (212) 686 7993 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Web site: www.cabi.org © CAB International 2001. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be repro- duced in any form or by any means, electronically, mechanically, by photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owners. A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library, London, UK. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Insects on palms / by Forrest W. Howard … [et al.]. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-85199-326-5 (alk. paper) 1. Palms--Diseases and pests. 2. Insect pests. 3. Insect pests--Control. I. Howard, F. W. SB608.P22 I57 2001 634.9’74--dc21 00-057965 ISBN 0 85199 326 5 Typeset by Columns Design Ltd, Reading Printed and bound in the UK by Biddles Ltd, Guildford and King’s Lynn Contents List of Boxes vii Authors and Contributors viii Acknowledgements x Preface xiii 1 The Animal Class Insecta and the Plant Family Palmae 1 Forrest W. Howard 2 Defoliators of Palms 33 Lepidoptera 34 Forrest W. Howard and Reynaldo G. Abad Coleoptera 81 Forrest W. -

Download Document

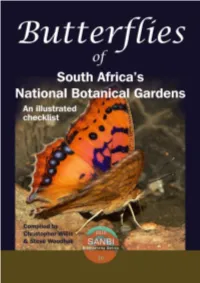

SANBI Biodiversity Series 16 Butterflies of South Africa’s National Botanical Gardens An illustrated checklist compiled by Christopher K. Willis & Steve E. Woodhall Pretoria 2010 SANBI Biodiversity Series The South African National Biodiversity Institute (SANBI) was established on 1 Sep- tember 2004 through the signing into force of the National Environmental Manage- ment: Biodiversity Act (NEMBA) No. 10 of 2004 by President Thabo Mbeki. The Act expands the mandate of the former National Botanical Institute to include responsibili- ties relating to the full diversity of South Africa’s fauna and flora, and builds on the internationally respected programmes in conservation, research, education and visitor services developed by the National Botanical Institute and its predecessors over the past century. The vision of SANBI: Biodiversity richness for all South Africans. SANBI’s mission is to champion the exploration, conservation, sustainable use, appre- ciation and enjoyment of South Africa’s exceptionally rich biodiversity for all people. SANBI Biodiversity Series publishes occasional reports on projects, technologies, work- shops, symposia and other activities initiated by or executed in partnership with SANBI. Photographs: Steve Woodhall, unless otherwise noted Technical editing: Emsie du Plessis Design & layout: Sandra Turck Cover design: Sandra Turck Cover photographs: Front: Pirate (Christopher Willis) Back, top: African Leaf Commodore (Christopher Willis) Back, centre: Dotted Blue (Steve Woodhall) Back, bottom: Green-veined Charaxes (Christopher Willis) Citing this publication WILLIS, C.K. & WOODHALL, S.E. (Compilers) 2010. Butterflies of South Africa’s National Botanical Gardens. SANBI Biodiversity Series 16. South African National Biodiversity Institute, Pretoria. ISBN 978-1-919976-57-0 © Published by: South African National Biodiversity Institute. -

A Handbook on the Rare, Threatened & Endemic Species of the Greater St Lucia Wetland Park

f A HANDBOOK ON THE RARE, THREATENED & ENDEMIC SPECIES OF THE GREATER ST LUCIA WETLAND PARK A product of the Greater St Lucia Wetland Park Rare, Threatened & Endemic Species Project Combrink & Kyle June 2006 St Lucia Office: The Dredger Harbour, Private Bag x05, St Lucia 3936 Tel No. +27 35 590 1633, Fax No. +27 35 590 1602, e-mail [email protected] 2 “Suddenly, as rare things will, it vanished” Robert Browning A photograph taken in 2003 of probably the last known Bonatea lamprophylla, a recently (1976) described terrestrial orchid that was known from three small populations, all within the Greater St Lucia Wetland Park. Nothing was known on the biology or life history of this species, except that it produced spectacular flowers between September and October. This orchid might have to be reclassified in the future as extinct. Suggested citation for this product: Combrink, A.S. and Kyle, R. 2006. A Handbook on the Rare, Threatened & Endemic Species of the Greater St Lucia Wetland Park. A product of the Greater St Lucia Wetland Park - Rare, Threatened & Endemic Species Project. Unpublished internal report. 191 pp. 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 FOREWORD............................................................................................................................................ 6 2 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................... 7 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..................................................................................................................... -

Dissertationlouiskwakuamprako.Pdf (3.643Mb)

Challenges to ecosystem services of sustainable agriculture in West Africa Amprako, Louis Dissertation for the acquisition of the academic degree Doktor der Agrarwissenschaften (Dr. agr.) Presented to the Faculty of Organic Agricultural Sciences Organic Plant Production and Agroecosystems Research in the Tropics and Subtropics (OPATS) First supervisor: Prof. Dr. Andreas Buerkert Second supervisor: Dr. habil. Regina Roessler University of Kassel, Witzenhausen Germany Date of submission: 10.06.2020 Date of defence : 15.07.2020 Contents 1 Chapter 1 1 1.1 General introduction ....................... 2 1.2 Population development in West Africa ............. 2 1.3 Agroecosystems in Africa ..................... 3 1.4 The African livestock revolution: an option for enhanced sus- tainability? ............................ 4 1.5 The biochar revolution: an option for agricultural efficiency and sustainability in Africa? ................... 5 1.6 Study area ............................. 6 1.7 Study objectives and hypotheses ................. 7 1.8 References . 8 2 Chapter 2 12 2.1 Introduction ............................ 14 2.1.1 Livestock production in the Sahel . 14 2.1.2 Livestock production in Mali . 14 2.1.3 Site description ...................... 15 2.2 Methods .............................. 16 2.2.1 Data collection: Primary data on flows of livestock and animal feed ........................ 16 2.2.2 Data processing and analysis . 18 2.2.3 Limitations of the study . 19 2.3 Results and discussion ...................... 20 2.3.1 Scale, seasonality, and sources of livestock flows . 20 2.3.2 Direction of livestock flows . 23 2.3.2.1 Incoming livestock flows . 23 2.3.2.2 Outgoing livestock flows . 24 2.3.2.3 Transits ..................... 24 2.3.2.4 Incoming feed flows . -

PESTS of the COCONUT PALM Mi Pests and Diseases Are Particularly Important Among the Factors Which Limit Agricultural Production and Destroy Stored Products

PESTS of the COCONUT PALM mi Pests and diseases are particularly important among the factors which limit agricultural production and destroy stored products. This publication concerns the pests of the coconut palm and is intended for the use of research workers, personnel of plant protection services and growers Descriptions are given for each pest (adult or early stages), with information on the economic importance of the species the type of damage caused, and the control measures which have been applied (with or without success) up to the present time. The text deals with 110 species of insects which attack the palm in the field; in addition there arc those that attack copra in storage, as well as the various pests that are not insects This is the first of a series of publications on the pests and diseases of economically importani plants and plant products, and is intended primarily to fill a gap in currently available entomological and phytopathological literature and so to assist developing countries. PESTS OF THE COCONUT PALM Copyrighted material FAO Plant Production and Protection Series No. 18 PESTS OF THE COCONUT PALM b R.J.A.W. Lever FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS Rome 1969 Thl 6 One 0A8R-598-HSG9 First printing 1969 Second printing 1979 P-14 ISBN 92-5-100857-4 © FAO 1969 Printed in Italy Copyrighted material FOREWORD Shortage of food is still one of the most pressing problems in many countries. Among the factors which limit agricultural production and destroy stored products, pests and diseases are particularly important. -

The Butterflies and Skippers (Lepidoptera: Papilionoidea) of Angola: an Updated Checklist

Chapter 10 The Butterflies and Skippers (Lepidoptera: Papilionoidea) of Angola: An Updated Checklist Luís F. Mendes, A. Bivar-de-Sousa, and Mark C. Williams Abstract Presently, 792 species/subspecies of butterflies and skippers (Lepidoptera: Papilionoidea) are known from Angola, a country with a rich diversity of habitats, but where extensive areas remain unsurveyed and where systematic collecting pro- grammes have not been undertaken. Only three species were known from Angola in 1820. From the beginning of the twenty-first century, many new species have been described and more than 220 faunistic novelties have been assigned. As a whole, of the 792 taxa now listed for Angola, 57 species/subspecies are endemic and almost the same number are known to be near-endemics, shared by Angola and by one or another neighbouring country. The Nymphalidae are the most diverse family. The Lycaenidae and Papilionidae have the highest levels of endemism. A revised check- list with taxonomic and ecological notes is presented and the development of knowl- edge of the superfamily over time in Angola is analysed. Keywords Africa · Conservation · Ecology · Endemism · Taxonomy L. F. Mendes (*) Museu Nacional de História Natural e da Ciência, Universidade de Lisboa, Lisboa, Portugal CIBIO, Centro de Investigação em Biodiversidade e Recursos Genéticos, Vairão, Portugal e-mail: [email protected] A. Bivar-de-Sousa Museu Nacional de História Natural e da Ciência, Universidade de Lisboa, Lisboa, Portugal Sociedade Portuguesa de Entomologia, Lisboa, Portugal e-mail: [email protected] M. C. Williams Pretoria University, Pretoria, South Africa e-mail: [email protected] © The Author(s) 2019 167 B. -

Butterflies of the "Four Corners Area"

AWF FOUR CORNERS TBNRM PROJECT : REVIEWS OF EXISTING BIODIVERSITY INFORMATION i Published for The African Wildlife Foundation's FOUR CORNERS TBNRM PROJECT by THE ZAMBEZI SOCIETY and THE BIODIVERSITY FOUNDATION FOR AFRICA 2004 PARTNERS IN BIODIVERSITY The Zambezi Society The Biodiversity Foundation for Africa P O Box HG774 P O Box FM730 Highlands Famona Harare Bulawayo Zimbabwe Zimbabwe Tel: +263 4 747002-5 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.biodiversityfoundation.org Website : www.zamsoc.org The Zambezi Society and The Biodiversity Foundation for Africa are working as partners within the African Wildlife Foundation's Four Corners TBNRM project. The Biodiversity Foundation for Africa is responsible for acquiring technical information on the biodiversity of the project area. The Zambezi Society will be interpreting this information into user-friendly formats for stakeholders in the Four Corners area, and then disseminating it to these stakeholders. THE BIODIVERSITY FOUNDATION FOR AFRICA (BFA is a non-profit making Trust, formed in Bulawayo in 1992 by a group of concerned scientists and environmentalists. Individual BFA members have expertise in biological groups including plants, vegetation, mammals, birds, reptiles, fish, insects, aquatic invertebrates and ecosystems. The major objective of the BFA is to undertake biological research into the biodiversity of sub-Saharan Africa, and to make the resulting information more accessible. Towards this end it provides technical, ecological and biosystematic expertise. THE ZAMBEZI SOCIETY was established in 1982. Its goals include the conservation of biological diversity and wilderness in the Zambezi Basin through the application of sustainable, scientifically sound natural resource management strategies.