Regional Security Cooperation in the East African Community

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uganda People's Congress and National Resistance

UGANDA PEOPLE'S CONGRESS AND NATIONAL RESISTANCE MOVEMENT By Yoga Adhola The National Resistance Movement (NRM) is a movement to resist UPC or what UPC stands for, i.e. national-democratic liberation. The earliest incidence of this resistance is given to us by none other than the founder of the NRM, Yoweri Museveni. He recounts: We were staunchly anti-Obote. On 22 February 1966, the day he arrested five members of his cabinet, three of us, Martin Mwesigwa, Eriya Kategaya and myself went to see James Kahigiriza, who was the Chief Minister of Ankole, to inquire about the possibility of going into exile to launch an armed struggle. Kahigiriza discouraged us, saying that we should give Obote enough time to fall by his own mistakes. We saw him again a few weeks later and he gave us the example of Nkrumah, who had been overthrown in Ghana by a military coup two days after Obote's abrogation of the Uganda constitution. Kahigiriza advised us that Nkrumah's example showed that all dictators were bound to fall in due course. Inwardly we were not convinced. We knew that dictators had to be actively opposed and that they would not just fall off by themselves like ripe mangoes. Later I went to Gayaza High School with Mwesigwa to contact Grace Ibingira's sister in order to find out whether she knew of any plans afoot to resist Obote's dictatorship. She, however, did not know of any such plan. We came to the conclusion that the old guard had no conception of defending people’s rights and we resolved to strike on our own. -

The Return to Makerere

7 My Experience: The Return to Makerere My Long Years at Makerere as Vice Chancellor (1993 – 2004) “We have decided to send you back to Makerere as the next Vice-Chancellor”. These were the words of Minister Amanya Mushega when I met him at a meeting at the International Conference Centre on September 20, 1993; and they are still fresh in my memory. Towards the end of August 1993, I was selected to accompany Mr Eriya Kategaya, who was then First Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Foreign Affairs, on a study visit to Bangladesh. The other members of the delegation were Mr David Pulkol who was then the Deputy Minister of Education and Sports and Johnson Busingye (now deceased) who was at the time the District Education Officer of Bushenyi. The purpose of the visit was to learn about the Grameen Micro-finance and the educational programmes for rural poor communities, which Dr Muhammad Yunus had established in Bangladesh, and to assess the possibility of replicating them in Uganda. On our way back from Dhaka, we had a stop-over at Addis Ababa Airport. The Ethiopian Government officials arranged for Mr David Pulkol and his delegation to wait for the Entebbe flight at the VIP lounge. Mr Kategaya had left us behind in Dhaka for a trip to Europe, so Mr Pulkol was now the leader of our delegation. For some reason, as we waited for our flight, the topic of dismissing senior Government officials over the radio came up. We thought that the practice of doing things in an uncivilised way had ended with Idi Amin, pointing out that the affected officers had a right to know their fate before the public did. -

Magazine2020 Contents Foreword 1

Magazine2020 Contents Foreword 1 Editor’s Note 3 Minister’s Statement 4 NRM to Prevail in 2021 Elections 7 The Value of Power 10 Salim Saleh’s Contribution14 Ibanda District at A Glance 17 Eriya Kategaya’s Contribution19 Museveni’s Six Contributions to the Region21 NRM’s Principles in Perspective25 Museveni’s 200 Km Trek to Birembo 27 Kidepo Valley National Park29 Human Wildlife Conflict32 Ugandans in Diaspora 36 NAADS Contributions38 Ibanda Woman MP 42 Afrika Kwetu Trek 45 Culture and HIV Prevention in Uganda 48 NRM Achivements 51 Urbanization Will Lead to Proper Land Usage 54 NRM Struggle and Uganda’s Diplomacy 56 Midwife who risked her life 59 Reliving Kampala’s Iconic Structures 61 Uganda Airlines A Big Plus for Tourism 65 Restoration of Security has Ensured Socio-Economic Transformation68 Transformation of Ibanda District Under the NRM Government 70 For the youth this Liberation Day73 Industrialization A Solution to Uganda’s Youth Unemployment75 Innovation, the driver to social economic transformation for Uganda78 ii Celebrating NRM/NRA patriotic struggle that ushered in national unity and socio-economic transformation Foreword iberation Day in Uganda activist group allied with the national army, UNLA, is celebrated every 26th of African Liberation Movements revolted and toppled Obote January, in remembrance while studying Political Science and were in turned chased out L and Economics in Tanzania. of power by the NRA. and commemoration of when Later, following Idi Amin’s coup the National Resistance Army/ Following two decades of of 1971, Museveni went into Movement (NRA/M) gallant ruin, decay and state collapse, exile and formed the Front for fighters captured state power NRA/M emerged victorious, National Salvation (FRONASA), after a five-year protracted and since then Uganda has merged and fought alongside enjoyed three decades of peoples struggle, and ushered other Ugandan groups and unprecedented success story in a fundamental change in Tanzanians to topple Amin in of macro-economic reforms, 1986. -

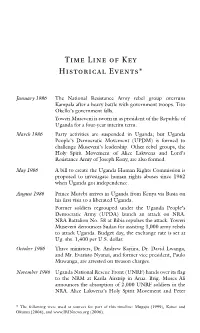

Time Line of Key Historical Events*

Time Line of Key Historical Events* January 1986 The National Resistance Army rebel group overruns Kampala after a heavy battle with government troops. Tito Okello’s government falls. Yoweri Museveni is sworn in as president of the Republic of Uganda for a four-year interim term. March 1986 Party activities are suspended in Uganda; but Uganda People’s Democratic Movement (UPDM) is formed to challenge Museveni’s leadership. Other rebel groups, the Holy Spirit Movement of Alice Lakwena and Lord’s Resistance Army of Joseph Kony, are also formed. May 1986 A bill to create the Uganda Human Rights Commission is proposed to investigate human rights abuses since 1962 when Uganda got independence. August 1986 Prince Mutebi arrives in Uganda from Kenya via Busia on his first visit to a liberated Uganda. Former soldiers regrouped under the Uganda People’s Democratic Army (UPDA) launch an attack on NRA. NRA Battalion No. 58 at Bibia repulses the attack. Yoweri Museveni denounces Sudan for assisting 3,000 army rebels to attack Uganda. Budget day, the exchange rate is set at Ug. shs. 1,400 per U.S. dollar. October 1986 Three ministers, Dr. Andrew Kayiira, Dr. David Lwanga, and Mr. Evaristo Nyanzi, and former vice president, Paulo Muwanga, are arrested on treason charges. November 1986 Uganda National Rescue Front (UNRF) hands over its flag to the NRM at Karila Airstrip in Arua. Brig. Moses Ali announces the absorption of 2,000 UNRF soldiers in the NRA. Alice Lakwena’s Holy Spirit Movement and Peter * The following were used as sources for part of this timeline: Mugaju (1999), Kaiser and Okumu (2004), and www.IRINnews.org (2006). -

HOSTILE to DEMOCRACY the Movement System and Political Repression in Uganda

HOSTILE TO DEMOCRACY The Movement System and Political Repression in Uganda Human Rights Watch New York $$$ Washington $$$ London $$$ Brussels Copyright 8 August 1999 by Human Rights Watch. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. ISBN 1-56432-239-4 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 99-65985 Cover design by Rafael Jiménez Addresses for Human Rights Watch 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th Floor, New York, NY 10118-3299 Tel: (212) 290-4700, Fax: (212) 736-1300, E-mail: [email protected] 1522 K Street, N.W., #910, Washington, DC 20005-1202 Tel: (202) 371-6592, Fax: (202) 371-0124, E-mail: [email protected] 33 Islington High Street, N1 9LH London, UK Tel: (171) 713-1995, Fax: (171) 713-1800, E-mail: [email protected] 15 Rue Van Campenhout, 1000 Brussels, Belgium Tel: (2) 732-2009, Fax: (2) 732-0471, E-mail:[email protected] Web Site Address: http://www.hrw.org Listserv address: To subscribe to the list, send an e-mail message to [email protected] with Asubscribe hrw-news@ in the body of the message (leave the subject line blank). Human Rights Watch is dedicated to protecting the human rights of people around the world. We stand with victims and activists to prevent discrimination, to uphold political freedom, to protect people from inhumane conduct in wartime, and to bring offenders to justice. We investigate and expose human rights violations and hold abusers accountable. We challenge governments and those who hold power to end abusive practices and respect international human rights law. We enlist the public and the international community to support the cause of human rights for all. -

Amin's Shadow

AR-6 Sub-Saharan Africa Andrew Rice is a Fellow of the Institute studying life, politics and development in ICWA Uganda and environs. LETTERS Amin’s Shadow By Andrew Rice DECEMBER 1, 2002 Since 1925 the Institute of KAMPALA, Uganda—One morning in early July 1972, Idi Amin’s men came for Current World Affairs (the Crane- police officer Joseph Ssali Sabalongo. As usual, there was no warning, no expla- Rogers Foundation) has provided nation. A group of soldiers simply burst into Ssali’s offices at the Buganda Road long-term fellowships to enable Courthouse in Kampala. Ali Towili, one of Amin’s thuggish sidekicks, waved a outstanding young professionals gun in the police officer’s face, marched him outside and forced him into the to live outside the United States trunk of a black Peugeot sedan. and write about international “I do not know the reason why I was picked up,” Ssali would tell a govern- areas and issues. An exempt ment commission in 1988, nine years after the dictator’s overthrow. “I was put operating foundation endowed by into a wet [trunk] containing fresh human blood; then I was led up to Naguru the late Charles R. Crane, the Public Safety Unit.” Institute is also supported by contributions from like-minded Ssali may not have known why he was taken, but he certainly would have individuals and foundations. known where he was headed—everyone was aware of what happened in Naguru. “The names of [Amin’s] torture centers had a certain black humor: Makerere Nurs- ing Home, Nakasero State Research Center, Naguru Public Safety Unit,” the TRUSTEES Uganda Commission of Inquiry into the Violation of Human Rights would write Bryn Barnard in its report. -

Uganda: No Resolution to Growing Tensions

UGANDA: NO RESOLUTION TO GROWING TENSIONS Africa Report N°187 – 5 April 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................................... i I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 1 II. UNRESOLVED ISSUES OF NATIONAL INTEGRATION ....................................... 2 A. THE PERSISTENCE OF ETHNIC, REGIONAL AND RELIGIOUS DIVISIONS .......................................... 2 B. POST-INDEPENDENCE POLICIES .................................................................................................... 3 1. Obote and the UPC ...................................................................................................................... 3 2. Amin and military rule ................................................................................................................. 4 3. The interim period ........................................................................................................................ 5 4. Obote and the UPC again ............................................................................................................. 5 III. LEGACIES OF THE NRA INSURGENCY ................................................................... 6 A. NO-PARTY RULE ......................................................................................................................... 6 B. THE SHIFT TO PATRONAGE AND PERSONAL RULE ....................................................................... -

PRESS RELEASE: Multi-Sectoral Council of Ministers Considers Draft EAC Common Market Protocol

PRESS RELEASE: Multi-Sectoral Council of Ministers considers draft EAC Common Market Protocol National Identification Document, Access and use of Land, Permanent Residence still unresolved East African Community Headquarters, Arusha Tanzania, Thursday 9 April March 2009: The joint meeting of the Sectoral Council on Trade, Industry, Fiannce and Investment and that of Multi-Sectoral Council on EAC Common Market Protocol to consider among others the draft EAC Common Market Protocol has ended today in Kampala, Uganda. The joint meeting was officially opened by the Rt. Hon. Prime Minister and Minister of EAC Affairs of the Republic of Uganda, Hon. Eriya Kategaya, on behalf of H.E the Vice President of Uganda, Gilbert Bukenya. The opening ceremony was attended by among others; the Chairperson of EAC Council of Ministers and Minister of EAC Affairs of the Republic of Rwanda, Hon Monique Mukaruliza; Honourable Ministers, Permanent Secretaries, Ambassadors and High Commissioners, the Director General of EAC Directorate of Customs and Trade, Mr. Peter Kiguta, and the EAC Deputy Secretary General in charge of Projects and Programmes, Amb. Julius Onen. The Rt. Hon. Prime Minister welcomed delegates to Uganda and implored them to take advantage of their presence in Uganda to explore the full potential of the country. Hon. Kategaya re-affirmed the Government of Uganda’s strong commitment to regional integration and that solid national development can only be attained through the framework of regional cooperation. Hon. Kategaya urged the Partner States to realize consensus on the freedoms and rights of the East African people as enshrined in the proposed Draft Protocol, as this will enable the citizens to tap the benefits of the Common Market. -

The Politics of Constitution Making in Uganda © Copyright by the Endowment of the United States Institute of Peace

6 The Politics of Constitution Making in Uganda Aili Mari Tripp ince 1990, thirty-eight African consti- once was a broad-based government to a tutions have been rewritten, and eight much smaller circle of individuals. As Ann involved major revisions. Uganda re- Mugisha, a member of the opposition, wrote Swrote its constitution in 1995. Many of the in a 2004 Journal of Democracy article, “The constitutional changes witnessed throughout real transition taking place there is from a Africa have to do with individual rights and relatively enlightened and benevolent au- liberties, the rights of traditional authori- thoritarian regime . to a textbook case of © Copyrightties, the protection of customary by rights, the is- Endowmententrenched one-man rule.”1 A decade of after sues of land rights, and the rights of women. its passage, 119 amendments to the 1995 These issues were central to the constitution- constitution had been made, some of them themaking United process in Uganda; States however, the un- Institutekey changes to the ofearlier Peaceconstitution. It democratic outcomes in that country dem- was widely acknowledged that 70 percent of onstrate the ways in which these processes parliamentarians were openly bribed to give have often been politicized to serve the in- President Yoweri Museveni the two-thirds terests of those in power. vote needed to alter the constitution to allow Since the 1995 constitution was adopted, him a third term.2 Uganda has slid backward precipitously in How did such undemocratic outcomes respecting civil and political liberties. The emerge from a constitution-making process government increasingly has restricted the that was touted as unprecedented in its par- freedom of association, harassed and intimi- ticipatory character? To understand the prob- dated opposition members and media work- lems with Uganda’s constitution, one needs ers, attempted to ram through undemocratic to examine the broader context within which legislation in Parliament without a quorum, it was drafted, debated, and voted on. -

Pike, William, Combatants: a Memoir of the Bush War and the Press in Uganda, Independently Published, 2019, 294 Pages

122 Political chronicles of the African Great Lakes Region 2019 Chroniques politiques de l’Afrique des grands lacs 2019 Pike, William, Combatants: A memoir of the bush war and the press in Uganda, Independently Published, 2019, 294 pages Combatants begins with the author’s personal life story. William Pike was born in 1952 in Tanganyika, where his father served as Provincial Commissi- oner. He saved up to tour Afghanistan and studied at the University of York, where he wrote an essay on the Yugoslav Partisans resistance group. Little did he know that he would later get involved with another guerrilla struggle. In London, Pike worked as a writer and journalist, and became a political activist for the Labour Party, returning to independent Tanzania as a freelance journa- list in 1982. It was during his time in Swahili classes in Tanzania that he met Cathy Watson. They were married in Kampala on 3 June 1989. Pike was introduced to Uganda by Ben Matogo while studying at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS). “The School of Oriental and African Studies coffee bar changed my life for it was there that I met Ben Matogo” (p. 17). While in Tanzania, Pike had received a master’s scholarship to study at SOAS. Matogo introduced Pike to other leading Ugandan figures in exile, including Ruhakana Rugunda and Eriya Kategaya. Thus began Pike’s association with the rebel group that would take power in Uganda. Rugunda had invited the Africa Now magazine editor Richard Carver to visit Luwero and the National Resistance Army (NRA).13 The invitation was turned down and William Pike, in search of a big story that would make his name as a jour- nalist, asked for the opportunity to travel and interview the guerrillas. -

THE TRUTH BEHIND the RWANDA TRAGEDY by Mr

THE TRUTH BEHIND THE RWANDA TRAGEDY By Mr. Remigius Kintu The Following Document was prepared upon request and presented to the U.N. Tribunal on Rwanda, Arusha, Tanzania March 20, 2005 I come before you, Ladies and Gentlemen of this noble Tribunal which was instituted to search for the truth behind the heinous crimes committed in Rwanda. And upon you was charged the noble responsibility of dispensing justice where it is due. If I could borrow from the wisdom of great men and women of long ago, truth is not a function of public opinion or majority vote, nor does it stem from the wishes of the mighty and powerful, but rather it stands in its absolute properties regardless of opinions, purposes or values of anyone and transcends time and space. I want to borrow from the Greek play OEDIPUS REX by Sophocles. King Oedipus was disturbed by the immense suffering taking place in Thebes. The calamity in that land of Thebes was caused by the innocent blood of its King Laisos who was killed many years ago. Kreon told Oedipus what he heard from Delphi that the gods demand we expel from the land of Thebes an old defilement we are sheltering. As a result, Oedipus made the following pledge: If any man knows by whose hand king Laios son of Ladbakos met his death, I direct that man to tell me everything no matter what he fears for having so long withheld it. Let it stand as promised that no further trouble will come to him but he may leave the land in safety. -

Cmiworkingpaper

CMIWORKINGPAPER Turnaround: The National Resistance Movement and the Re-introduction of a Multiparty System in Uganda Sabiti Makara, Lise Rakner, Lars Svåsand WP 2007: 12 Turnaround: The National Resistance Movement and the Re-introduction of a Multiparty System in Uganda Sabiti Makara, Lise Rakner and Lars Svåsand WP 2007: 12 CMI Working Papers This series can be ordered from: Chr. Michelsen Institute P.O. Box 6033 Postterminalen, N-5892 Bergen, Norway Tel: + 47 55 57 40 00 Fax: + 47 55 57 41 66 E-mail: [email protected] www.cmi.no Price: NOK 50 ISSN 0804-3639 ISBN 978-82-8062-219-8 This report is also available at: www.cmi.no/publications Indexing terms Political systems National resistance Elections Uganda Project title The 2006 Presidential and Parliamentary Elections in Uganda: Institutional and Legal Context Project number 24076 Contents INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................ 1 THE MOVEMENT POLITICAL SYSTEM IN UGANDA .......................................................................... 1 THE DECISION TO RE-INTRODUCE THE MULTI PARTY SYSTEM.......................................................................... 2 WHY DID THE NRM ABANDON ITS MONOPOLY POSITION AND EXPOSE ITSELF TO COMPETITION? ............................................................................................................................................. 3 INTERNAL AND EXTERNAL EXPLANATIONS FOR ORGANISATIONAL CHANGE ..................................................