Uganda People's Congress and National Resistance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Paper No. Makerere University Makerere

PAPER NO. MAKERERE UNIVERSITY MAKERERE INSTITUTE OF SOCIAL RESEARCH COMMUNAL CONFLICTS IN THE MILITARY AND ITS POLITICAL CONSEQUENCES By Dan Mudoola MAKERERE INSTITUTE OF SOCIAL RESEARCH Paper Presented to the Seroinar on "INTERNAL CONFLICT IK UGANDA", 21st - 26th September, 1987; Sponsored by International Alert London; MaJcerere Institute of Social Research, MaJcerere University; International Peace Research Institute, Oslo; and The United Nat Lons University, Tokyo. Views and opinions in this paper are the sole responsibility of the Author, not the sponsors' nor those of the organisation the author oomes from. the civil service and the judiciary, were defined. On the first Independence anniversary the constitution was amended to provide for a ceremonial president to replace the Governor-General. On the occasion of opening the first Independence. Parliament the Queen's representative, the Duke of Kent, members of the coalition UPC-KY government and, to some extent, members of the Opposition were in a sanguine self-congratulatory mood. The Duke of Kent promised thai his Government "would foster the spirit of tolerance and goodwill between all the peoples of Uganda - It would - pay due heed to the traditional beliefs and customs of the diverse peoples of Uganda. It would respect individual rights of the oommon man. It' would recognise the special status and dignity of the Hereditary Rulers of the Kingdoms and of the Constitutional Heads of the Districts". In equal measure, the Prime Minister, Apolo Milton Obote:, believed that "'traditional institutions would form a firm foundation upon which our newly independent state could be _ 3 advanoed." The leader of the Opposition, Basil Bataringays however, oautioned against "'tribalism and factionalism, our: two most deadly enemies - and unless we sen .acquire - • a sense of common purpose? - we can never be sure that our future path vri.ll be; entirely smooth1^- - Within a space of less than four years another actor v/ho had never been pert of the political calculations leading to independence- came to the scene. -

Regional Security Cooperation in the East African Community

REGIONAL SECURITY COOPERATION IN THE EAST AFRICAN COMMUNITY SABASTIANO RWENGABO BA (First Class) (Hons.), MA (Pub Admin. & Mgt), MAK. A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE 2014 DECLARATION I, Sabastiano RWENGABO, declare that this thesis is my original work. It has been written by me in its entirety. I have duly acknowledged all the sources of information which have been used in the thesis. The thesis has also not been previously written or submitted for any degree or any other award in any University or institution. ____________ _______________ Sabastiano RWENGABO 21 July 2014 i | P a g e Acknowledgement Along this journey I met many people who help me through the long, bumpy, road to and through Graduate School. It is impossible to acknowledge even a good fraction of them. I hope and pray that all those who supported me but find their names unmentioned here bear with me and accept that I do highly appreciate their invaluable contributions. From my parents who sent me to, and supported me through, formal schooling; through my brothers and sisters–the Rutashoborokas–to my family members–the Rwengabos–and relatives, my closest people endured my long absence while inspiring and supporting me invaluably. Your support and prayers helped me romp through doctoral manoeuvres. My Academic Advisors–Prof Janice Bially-Mattern; Prof Reuben Wong; Dr Karen Jane Winzoski–advised and mentored me, reading and re-reading my work countless times. They kept me on track, “in one shape” until we all saw “some light at the end of the tunnel.” Other Professors in the Department and beyond–Terence Lee, Luke David O’Sullivan, Kevin McGahan, Jamie Davidson, Chen An, Tobias Hofmann, Yoshinori Nishizaki, Robert Woodberry, Soo Yeon Kim, Terry Nardin, Shirlena Huang (Migration Cluster/Dean’s Office), Elaine Ho (Geography/Migration Cluster)–taught and advised me through the many modules, teaching tasks, and engagements in and outside the department, the University, and the World. -

@Bernadette A. Da Silva Montreal. Qu,Bec

f - .. ,. , lI' .. 1 , l" i j• • McGUL UNIVERSITY 1 THE POST-COLONIAL STATE: UGAIDA 1962 - 1971. A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE . FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES AND RESEARCH -IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQl1IREMEMS FOR THE DEGREE OF MiSTER OF ARTS BI @Bernadette A. Da Silva Montreal. Qu,bec August 1985. 1 s • • ABSTRACT u .. • . The lIubJect of th!. thesie 18 the nature ot the poet- oolonial ita te in Atriea as exe.pl1tled by the proeusee ot ..tate for •• tion in Uganda ,during the 1962-71 periode It h the contention of the theeh thaet an 9bderetanding or, thele • proceeeu le neceeearl for an underetandlng of the poet colonial etate. state for ..tion ie a direct r.sponee on the part of poli tical leader.' to the preesuree and proble.s created bl eoc1eta(l. tCJt'oes. Thue, a study of these proeellee will shed turther ~léht on the ralationshlpe betw.en varloue , , eoeietal toroes.... ae _11 ae betlleeri eocletal forcee and the • ta te. Thie Ihould, in turn, enable us ta &see 8 e th, nature of the atate, in part1cular vhe~her It existe at aIl, and if la whether i t playl an Instru.ental role or whether l.t i8 art autotlQaous to'rce. On the buie ot the U,anda aaterlal, the f thesis telte the varloue hlpothe818 re,ardlng the funct1011B of \ the etate and concludee tha~.whlle it do~ndeed exiet, the ·f at•. t. ".(acII ~any eonltra1nta on He autono.y, a eondition re , tll"Cted in the poli~ee puraued bl the poli tical leaderehip ot the country. -

Nternational Alert

PAPER NO. PAP/004 MAKERERE UNIVERSITY MAKERERE INSTITUTE OF SOCIAL RESEARCH/INTERNATIONAL ALERT ETHNIC PLURALISM AND POLITICAL CENTRALISATION"': THE BASIS OF POLITICAL CONFLICT IN UGANDA INSTITUTE OF j D:vt. C :NT STUDIES LIBRARY Dr. Y. BARONGO, Associate Professor, Department of Political Science, Makerere University Paper presented to the International Seminar on Internal Conflict, 21st - 26th September, 1987; sponsored by International Alert, London; Makerere Institute of Social Research, Makerere University; International Peace Research Institute, Oslo; and The United Nations University, Tokyo. Views and opinions in this paper are the sole responsibility of the author, not the sponsors' nor those of the organisation the author comes from. an& the struggle of the elite members of ethnic groups to control the centre:, hightens'and intensifies political conflict. To many observers of the Ugandan political scene, particularly those of foreign (western) origins, the struggle for political power at' the centre among political elites from different ethnic backgrounds which in recent years has assumed violent dimensions, is an expression of ethnic or 'tribal' conflict and' hostility. Contrary to such views, this paper attempts to show that the violent conflicts that have bedevilled the Ugandan nation since the 1966 crisis, are purely political conflicts in origin, oaJuse and effect. The paper contends that the struggle for participation and control of political power at the centre, is one of the major causes of political conflict in this oountry. In the end, the paper advocates for the decentralization of power and the creation of a strong system of local govern- ment as means of minimizing political conflict in Uganda. -

The Return to Makerere

7 My Experience: The Return to Makerere My Long Years at Makerere as Vice Chancellor (1993 – 2004) “We have decided to send you back to Makerere as the next Vice-Chancellor”. These were the words of Minister Amanya Mushega when I met him at a meeting at the International Conference Centre on September 20, 1993; and they are still fresh in my memory. Towards the end of August 1993, I was selected to accompany Mr Eriya Kategaya, who was then First Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Foreign Affairs, on a study visit to Bangladesh. The other members of the delegation were Mr David Pulkol who was then the Deputy Minister of Education and Sports and Johnson Busingye (now deceased) who was at the time the District Education Officer of Bushenyi. The purpose of the visit was to learn about the Grameen Micro-finance and the educational programmes for rural poor communities, which Dr Muhammad Yunus had established in Bangladesh, and to assess the possibility of replicating them in Uganda. On our way back from Dhaka, we had a stop-over at Addis Ababa Airport. The Ethiopian Government officials arranged for Mr David Pulkol and his delegation to wait for the Entebbe flight at the VIP lounge. Mr Kategaya had left us behind in Dhaka for a trip to Europe, so Mr Pulkol was now the leader of our delegation. For some reason, as we waited for our flight, the topic of dismissing senior Government officials over the radio came up. We thought that the practice of doing things in an uncivilised way had ended with Idi Amin, pointing out that the affected officers had a right to know their fate before the public did. -

Magazine2020 Contents Foreword 1

Magazine2020 Contents Foreword 1 Editor’s Note 3 Minister’s Statement 4 NRM to Prevail in 2021 Elections 7 The Value of Power 10 Salim Saleh’s Contribution14 Ibanda District at A Glance 17 Eriya Kategaya’s Contribution19 Museveni’s Six Contributions to the Region21 NRM’s Principles in Perspective25 Museveni’s 200 Km Trek to Birembo 27 Kidepo Valley National Park29 Human Wildlife Conflict32 Ugandans in Diaspora 36 NAADS Contributions38 Ibanda Woman MP 42 Afrika Kwetu Trek 45 Culture and HIV Prevention in Uganda 48 NRM Achivements 51 Urbanization Will Lead to Proper Land Usage 54 NRM Struggle and Uganda’s Diplomacy 56 Midwife who risked her life 59 Reliving Kampala’s Iconic Structures 61 Uganda Airlines A Big Plus for Tourism 65 Restoration of Security has Ensured Socio-Economic Transformation68 Transformation of Ibanda District Under the NRM Government 70 For the youth this Liberation Day73 Industrialization A Solution to Uganda’s Youth Unemployment75 Innovation, the driver to social economic transformation for Uganda78 ii Celebrating NRM/NRA patriotic struggle that ushered in national unity and socio-economic transformation Foreword iberation Day in Uganda activist group allied with the national army, UNLA, is celebrated every 26th of African Liberation Movements revolted and toppled Obote January, in remembrance while studying Political Science and were in turned chased out L and Economics in Tanzania. of power by the NRA. and commemoration of when Later, following Idi Amin’s coup the National Resistance Army/ Following two decades of of 1971, Museveni went into Movement (NRA/M) gallant ruin, decay and state collapse, exile and formed the Front for fighters captured state power NRA/M emerged victorious, National Salvation (FRONASA), after a five-year protracted and since then Uganda has merged and fought alongside enjoyed three decades of peoples struggle, and ushered other Ugandan groups and unprecedented success story in a fundamental change in Tanzanians to topple Amin in of macro-economic reforms, 1986. -

Ot • 99 Jwt Aftaue, 7Th L'loar

•I> CVI/pbg 81r, I • poatehl to JOU tor t1ll4 lnter ta'te4 17 ~ w1 111l1ch :rau emcloMI. a t cnal. 1Drita'Uoa to • tzro. the Qotw!...n ot 1b nfa to a 1iM oelebr&tioaa ill a.p&1& tra. 8 to lO October. ! ream t, 1a 'rift ot the fM't tbat the am.ra1 »••*q v1ll. • 111 -•1oD at the t~ , I Y1l.l DOt 'M able to att.l tb8 DIU,_ ,..., •»~ u I woall. haw l.1W to 4c. J:t tile GoftZ rllt ot • I l.ike to I'CJB1 •te ..• 1[. J. , llnllll~awt. leeretar,r 111 ...... or eaa.o ClrilJ.a o,.raUca, to repre..t • at the ~ celabrattau. U th1a ~1oa aboal4 'M to tbll GowzwDt ot Vp-f• I woul4 .,.._t tllat tale ..taila -.r lie 1fOft.e4 out 111 RODnl.':tatlal v1tla •• .......... • ... c. ~- c:rc;R, c.... DaJIIV ~ .._._ta'Uft ot tbe ID1W Kjn.,_ to tM 8l1tel atioDe 99 JWt Aftaue, 7th l'loar ... York 16, ... York cc: u.x:. ltl.ssionJ Miss Gervais Mr. Amachree CVI/pbg str, I • IN t\11 to 10U tor k1ll4 let'ter clate4 17 ~ ¥1th 11b1ch :rou ac a tcaw&L ilm.atioa to • Goftn.ent ~ Up'* to atteDI 'tba ~ aelallll"''l~~:.. 1D ~ tro. 8 to lO October. I re t tbat , 1a 'Y'1Mr cd the t.at that tbe OeDaral » q w1ll be 1D •••1aa at tbe tt.1 I w1ll. :got 'be abla to atteDI 'tM 1e :Uou u I lib4 to do. It tile t ~ ....-• I like to :te llr. -

The Rise and Fall of Grace Ibingira

24 The rise and fall of Grace Ibingira PART TWO jobs were dished out on a tribal basis. It is not unlikely that FOLLOWING Gulu the UPC appeared to enjoy an upsurge. there are people in Kenya occupying certain positions which In August carpet crossers from the Democratic Party and Buganda's ll they could not earn in their own right had they not belonged to Kabaka Yekka ("Kabaka Alone ) swelled its parliamentary group this tribe or that. This is a factual albeit obviously bitter to an absolute majority and the coalition with KY was ended. observation; it is even bitterer because our leaders fail to In Buganda, the DP made more local level headway than did the pinpoint the existence of tribalism in the country. UPC but KY MP's continued to cross under the influence of This article is indeed aimed at spotlighting an evil whose Ibingira until only 7 of 24 remained, along with 8 DP and one mention in Kenya is frightening, to put it very mildly. But this ex - UPC trade union independent, on tne opposition benches. is a free and frank analysis offered of a nation which is striving Late in 1965 the then Opposition Leader, Basil Batcringaya (of to eliminate tribalism. How many times have leaders in the the DP and Ankole) had crossed with 5 other MP's and - it then Buluhyia area complained about the appointment of Kikuyu seemed - most of the DP machine. District Commissioners in their area? Is it not tribal ism that a Naturally the pol itical situation seemed well in hand. -

Exclusionary Elite Bargains and Civil War Onset: the Case of Uganda

Working Paper no. 76 - Development as State-making - EXCLUSIONARY ELITE BARGAINS AND CIVIL WAR ONSET: THE CASE OF UGANDA Stefan Lindemann Crisis States Research Centre August 2010 Crisis States Working Papers Series No.2 ISSN 1749-1797 (print) ISSN 1749-1800 (online) Copyright © S. Lindemann, 2010 This document is an output from a research programme funded by UKaid from the Department for International Development. However, the views expressed are not necessarily those of DFID. Crisis States Research Centre Exclusionary elite bargains and civil war onset: The case of Uganda Stefan Lindemann Crisis States Research Centre Uganda offers almost unequalled opportunities for the study of civil war1 with no less than fifteen cases since independence in 1962 (see Figure 1) – a number that makes it one of the most conflict-intensive countries on the African continent. The current government of Yoweri Museveni has faced the highest number of armed insurgencies (seven), followed by the Obote II regime (five), the Amin military dictatorship (two) and the Obote I administration (one).2 Strikingly, only 17 out of the 47 post-colonial years have been entirely civil war free. 7 NRA 6 UFM FEDEMO UNFR I FUNA 5 NRA UFM UNRF I FUNA wars 4 UPDA LRA LRA civil HSM ADF ADF of UPA WNBF UNRF II 3 Number FUNA LRA LRA UNRF I UPA WNBF 2 UPDA HSM Battle Kikoosi Maluum/ UNLA LRA LRA 1 of Mengo FRONASA 0 1962 1963 1964 1965 1966 1967 1968 1969 1970 1971 1972 1973 1974 1975 1976 1977 1978 1979 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 Figure 1: Civil war in Uganda, 1962-2008 Source: Own compilation. -

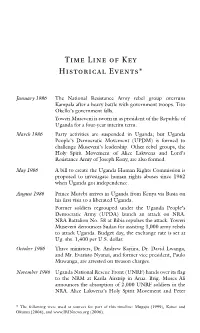

Time Line of Key Historical Events*

Time Line of Key Historical Events* January 1986 The National Resistance Army rebel group overruns Kampala after a heavy battle with government troops. Tito Okello’s government falls. Yoweri Museveni is sworn in as president of the Republic of Uganda for a four-year interim term. March 1986 Party activities are suspended in Uganda; but Uganda People’s Democratic Movement (UPDM) is formed to challenge Museveni’s leadership. Other rebel groups, the Holy Spirit Movement of Alice Lakwena and Lord’s Resistance Army of Joseph Kony, are also formed. May 1986 A bill to create the Uganda Human Rights Commission is proposed to investigate human rights abuses since 1962 when Uganda got independence. August 1986 Prince Mutebi arrives in Uganda from Kenya via Busia on his first visit to a liberated Uganda. Former soldiers regrouped under the Uganda People’s Democratic Army (UPDA) launch an attack on NRA. NRA Battalion No. 58 at Bibia repulses the attack. Yoweri Museveni denounces Sudan for assisting 3,000 army rebels to attack Uganda. Budget day, the exchange rate is set at Ug. shs. 1,400 per U.S. dollar. October 1986 Three ministers, Dr. Andrew Kayiira, Dr. David Lwanga, and Mr. Evaristo Nyanzi, and former vice president, Paulo Muwanga, are arrested on treason charges. November 1986 Uganda National Rescue Front (UNRF) hands over its flag to the NRM at Karila Airstrip in Arua. Brig. Moses Ali announces the absorption of 2,000 UNRF soldiers in the NRA. Alice Lakwena’s Holy Spirit Movement and Peter * The following were used as sources for part of this timeline: Mugaju (1999), Kaiser and Okumu (2004), and www.IRINnews.org (2006). -

HOSTILE to DEMOCRACY the Movement System and Political Repression in Uganda

HOSTILE TO DEMOCRACY The Movement System and Political Repression in Uganda Human Rights Watch New York $$$ Washington $$$ London $$$ Brussels Copyright 8 August 1999 by Human Rights Watch. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. ISBN 1-56432-239-4 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 99-65985 Cover design by Rafael Jiménez Addresses for Human Rights Watch 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th Floor, New York, NY 10118-3299 Tel: (212) 290-4700, Fax: (212) 736-1300, E-mail: [email protected] 1522 K Street, N.W., #910, Washington, DC 20005-1202 Tel: (202) 371-6592, Fax: (202) 371-0124, E-mail: [email protected] 33 Islington High Street, N1 9LH London, UK Tel: (171) 713-1995, Fax: (171) 713-1800, E-mail: [email protected] 15 Rue Van Campenhout, 1000 Brussels, Belgium Tel: (2) 732-2009, Fax: (2) 732-0471, E-mail:[email protected] Web Site Address: http://www.hrw.org Listserv address: To subscribe to the list, send an e-mail message to [email protected] with Asubscribe hrw-news@ in the body of the message (leave the subject line blank). Human Rights Watch is dedicated to protecting the human rights of people around the world. We stand with victims and activists to prevent discrimination, to uphold political freedom, to protect people from inhumane conduct in wartime, and to bring offenders to justice. We investigate and expose human rights violations and hold abusers accountable. We challenge governments and those who hold power to end abusive practices and respect international human rights law. We enlist the public and the international community to support the cause of human rights for all. -

Amin's Shadow

AR-6 Sub-Saharan Africa Andrew Rice is a Fellow of the Institute studying life, politics and development in ICWA Uganda and environs. LETTERS Amin’s Shadow By Andrew Rice DECEMBER 1, 2002 Since 1925 the Institute of KAMPALA, Uganda—One morning in early July 1972, Idi Amin’s men came for Current World Affairs (the Crane- police officer Joseph Ssali Sabalongo. As usual, there was no warning, no expla- Rogers Foundation) has provided nation. A group of soldiers simply burst into Ssali’s offices at the Buganda Road long-term fellowships to enable Courthouse in Kampala. Ali Towili, one of Amin’s thuggish sidekicks, waved a outstanding young professionals gun in the police officer’s face, marched him outside and forced him into the to live outside the United States trunk of a black Peugeot sedan. and write about international “I do not know the reason why I was picked up,” Ssali would tell a govern- areas and issues. An exempt ment commission in 1988, nine years after the dictator’s overthrow. “I was put operating foundation endowed by into a wet [trunk] containing fresh human blood; then I was led up to Naguru the late Charles R. Crane, the Public Safety Unit.” Institute is also supported by contributions from like-minded Ssali may not have known why he was taken, but he certainly would have individuals and foundations. known where he was headed—everyone was aware of what happened in Naguru. “The names of [Amin’s] torture centers had a certain black humor: Makerere Nurs- ing Home, Nakasero State Research Center, Naguru Public Safety Unit,” the TRUSTEES Uganda Commission of Inquiry into the Violation of Human Rights would write Bryn Barnard in its report.