Accepted Manuscript

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uncommon Books, Ephemera & Other Works on Paper

Uncommon Books, Ephemera & other works on Paper Asia Bookroom www.AsiaBookroom.com Page 1 Why Include Asian Material in Your Collection? Librarians and collectors are increasingly adding Asian materials to their collections with the aim of providing a more balanced resource that better reflects the world. Including an Asian perspective on a subject within your collection provides an interesting contrast to the more commonly collected Western focused themes and in doing so provides deeper insights into a world that scholars and collectors were frequently previously unaware of. If you might be interested in pursuing this direction Sally Burdon from Asia Bookroom can advise you. Sally has worked with libraries and collectors worldwide and would welcome the opportunity to discuss your collecting interests. Her business Asia Bookroom specialises exclusively in books, ephemera and other materials on paper with an Asian focus. Asia Bookroom Lawry Place We issue many specialised lists by email. Macquarie ACT 2614 Australia Join our mailing list. Ph: +61 2 6251 5191 Fax: +61 2 6251 5536 Email us on [email protected] or Website: www.AsiaBookroom.com visit our website www.AsiaBookroom.com Email: [email protected] Japan & Korea—19th Century Map With Somewhat Quirky English Captions 樺井達之輔 Kabai Tatsunosuke (Editor) 明治改正 大日本精圖 Meiji kaisei dainihon seizu Detailed Map of Great Japan: Revision in Meiji. Folding map measures 70 x 70.5cm a few small closed tears along folds, 3 small holes at folds with only tiny loss. A very nice map in good condition. Nakamura Asakichi 中 村淺吉 Kyoto. 1887. Coloured copperplate map of Japan with Hokkaido and Korea shown in vignettes at the upper left corner and Okinawa (Ryūkyū) and the Ogasawara Islands in vignettes in the upper middle section of the map in the middle and to the right are the Eastern and Western hemispheres. -

841D211f0b4bb19c93c26e63b9

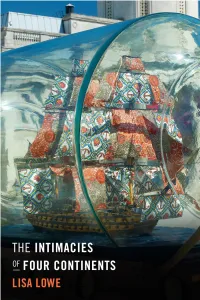

THE INTIMACIES OF FOUR CONTINENTS This page intentionally left blank THE INTIMACIES OF FOUR CONTINENTS LISA LOWE Duke University Press Durham and London 2015 © 2015 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid-f ree paper ∞ Typeset in Minion Pro by Westchester Publishing Services Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Lowe, Lisa. Te intimacies of four continents / Lisa Lowe. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 978-0-8223-5863-3 (hardcover : alk. paper) isbn 978-0-8223-5875-6 (pbk. : alk. paper) isbn 978-0-8223-7564-7 (e- book) 1. Liberalism. 2. Liberty. 3. Slave trade. 4. Commerce. 5. Civilization, Modern. i. Title. jc574.l688 2015 320.51— dc23 2014046258 Cover art: Nelson’s Ship in a Bottle, © Yinka Shonibare mbe. All rights reserved, dAcs/ ars, NY 2014. Photo courtesy Stephen Friedman Gallery, London, and National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, UK. for Juliet This page intentionally left blank CONTENTS CHAPTER 1. THE INTIMACIES OF FOUR CONTINENTS * 1 CHAPTER 2. AUTOBIOGRAPHY OUT OF EMPIRE * 43 CHAPTER 3. A FETISHISM OF COLONIAL COMMODITIES * 73 CHAPTER 4. THE RUSES OF LIBERTY * 101 CHAPTER 5. FREEDOMS YET TO COME * 135 AC KNOW L EDG MENTS * 177 NOTES * 181 REFERENCES * 269 INDEX * 305 1.1 Cutting Sugar Cane in Trinidad, Richard Bridgens (1836). Lithograph from West India Scenery, by Richard Bridgens. © Te British Library Board. CHAPTER 1 THE INTIMACIES OF FOUR CONTINENTS My study investigates the ofen obscured connections between the emer- gence of Eur o pean liberalism, settler colonialism in the Americas, the transatlantic African slave trade, and the East Indies and China trades in the late eigh teenth and early nineteenth centuries. -

List of Presidents of the Legislative Council and His Date of Presidency Since 1843

List of Presidents of the Legislative Council and his date of Presidency since 1843 The Right Honourable Sir Henry POTTINGER, Bt, PC, GCB 26.6.1843 Sir John Francis DAVIS , Bt, KCB 8.5.1844 Sir Samuel George BONHAM, Bt, KCB 21.3.1848 Sir John BOWRING 13.4.1854 The Right Honourable the Lord ROSMEAD, PC, GCMG 9.9.1859 Sir Richard Graves MacDONNELL, KCMG, CB 11.3.1866 Sir Arthur Edward KENNEDY, GCMG, CB 16.4.1872 Sir John Pope HENNESSY, KCMG 22.4.1877 The Right Honourable Sir George Ferguson BOWEN, PC, GCMG 30.3.1883 Sir George William DES VOEUX, GCMG 6.10.1887 Sir William ROBINSON, GCMG 10.12.1891 Sir Henry Arthur BLAKE, GCMG 25.11.1898 The Right Honourable Sir Matthew NATHAN, PC, GCMG 29.7.1904 The Right Honourable the Lord LUGARD, PC, GCMG, CB, DSO 29.7.1907 Sir Francis Henry MAY, GCMG 24.7.1912 Sir Reginald Edward STUBBS, GCMG 30.9.1919 Sir Cecil CLEMENTI, GCMG 1.11.1925 Sir William PEEL, KCMG, KBE 9.5.1930 Sir Andrew CALDECOTT, GCMG, CBE, 12.12.1935 Sir Geoffry Alexander Stafford NORTHCOTE, KCMG 28.10.1937 Sir Mark Aitchison YOUNG, GCMG 10.9.1941 Sir Alexander William George Herder GRANTHAM, GCMG 25.7.1947 Sir Robert Brown BLACK, GCMG, OBE 23.1.1958 Sir David Clive Crosbie TRENCH, GCMG, MC 14.4.1964 Lord MacLEHOSE of Beoch, KT, GBE, KCMG, KCVO 19.11.1971 Sir Edward YOUDE, GCMG, GCVO, MBE 20.5.1982 Lord WILSON of Tillyorn, GCMG 9.4.1987 The Right Honourable Christopher Francis PATTEN 9.7.1992 Sir Joseph SWAINE, CBE, LLD, QC, JP 19.2.1993 The Honourable Andrew WONG Wang-fat, OBE, JP 11.10.1995 The Honourable Mrs Rita FAN HSU Lai-tai, GBM, GBS, JP 2.7.1998 * President of the Provisional Legislative Council (1997-1998) The Honourable Jasper TSANG Yok-sing, GBM, GBS, JP 8.10.2008 The Honourable Andrew LEUNG Kwan-yuen, GBM, GBS, JP 12.10.2016 . -

This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. In their Own Words: British Sinologists’ Studies on Chinese Literature, 1807–1901 Lingjie Ji Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Asian Studies (Chinese) School of Literatures, Languages and Cultures The University of Edinburgh 2017 Declaration I hereby affirm that all work in this thesis is my own work and has been composed by me solely. No part of this thesis has been submitted for any other degree or professional qualification. Signed: Name: Lingjie Ji Date: 23/11/2017 Abstract of Thesis See the Postgraduate Assessment Regulations for Research Degrees: www.ed.ac.uk/schools-departments/academic-services/policies- regulations/regulations/assessment Name of student: Lingjie Ji UUN S1356381 University email: [email protected] Degree sought: Doctorate No. of words in the 95083 main text of thesis: Title of thesis: In Their Own Words: British Sinologists’ Studies on Chinese Literature, 1807–1901 Insert the abstract text here - the space will expand as you type. -

Maritime Raiding, International Law and the Suppression of Piracy on the South China Coast, 1842–1869

Jonathan Chappell Maritime raiding, international law and the suppression of piracy on the south China coast, 1842–1869 Article (Accepted version) (Refereed) Original citation: Chappell, Jonathan (2018) Maritime raiding, international law and the suppression of piracy on the south China coast, 1842–1869. International History Review, 40 (3). pp. 473-492. ISSN 0707-5332 DOI: 10.1080/07075332.2017.1334689 © 2017 Informa UK Limited This version available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/88339/ Available in LSE Research Online: June 2018 LSE has developed LSE Research Online so that users may access research output of the School. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in LSE Research Online to facilitate their private study or for non-commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. You may freely distribute the URL (http://eprints.lse.ac.uk) of the LSE Research Online website. This document is the author’s final accepted version of the journal article. There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. Maritime Raiding, International Law and the Suppression of Piracy on the South China Coast, 1842-1869 Author: Jonathan Chappell Affiliation: New York University Shanghai Funding Acknowledgements: This work was supported by the United Kingdom Arts and Humanities Research Council under grant AH/K502947/1 and the Chiang Ching-kuo Foundation for International Scholarly Exchange under grant DD024-U-14. -

The British State at the Margins of Empire Extraterritoriality and Governance in Treaty Port China, 1842-1927

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from Explore Bristol Research, http://research-information.bristol.ac.uk Author: Thompson, Alex Title: The British state at the margins of empire extraterritoriality and governance in treaty port China, 1842-1927 General rights Access to the thesis is subject to the Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial-No Derivatives 4.0 International Public License. A copy of this may be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode This license sets out your rights and the restrictions that apply to your access to the thesis so it is important you read this before proceeding. Take down policy Some pages of this thesis may have been removed for copyright restrictions prior to having it been deposited in Explore Bristol Research. However, if you have discovered material within the thesis that you consider to be unlawful e.g. breaches of copyright (either yours or that of a third party) or any other law, including but not limited to those relating to patent, trademark, confidentiality, data protection, obscenity, defamation, libel, then please contact [email protected] and include the following information in your message: •Your contact details •Bibliographic details for the item, including a URL •An outline nature of the complaint Your claim will be investigated and, where appropriate, the item in question will be removed from public view as soon as possible. The British state at the margins of empire: extraterritoriality and governance in treaty port China, 1842-1927 Alexander Thompson A dissertation submitted to the University of Bristol in accordance with the requirements for award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Arts, May 2018. -

Performing China on the London Stage Ashley Thorpe Performing China on the London Stage

Performing China on the London Stage Ashley Thorpe Performing China on the London Stage Chinese Opera and Global Power, 1759–2008 Ashley Thorpe Royal Holloway, University of London, UK ISBN 978-1-137-59785-4 ISBN 978-1-137-59786-1 (eBook) DOI 10.1057/978-1-137-59786-1 Library of Congress Control Number: 2016949254 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2016 The author(s) has/have asserted their right(s) to be identifi ed as the author(s) of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. This work is subject to copyright. All rights are solely and exclusively licensed by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifi cally the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfi lms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specifi c statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the pub- lisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. -

A Catalogue of the Library of the North China

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. http://books.google.com ,► A CATALOGUE OF THE LIBRARY OF THE NORTH CHINA BRANCH OF THE EOYAL ASIATIC SOCIETY (INCLUDING THE LIBRARY OF ALEX. WYLIE, ESQ.) Systematically classed. BI HENRI CORDIER, HON. LIBRARIAN. SHANGHAI: PRINTED AT THE " CIIINO-FOOXO " GENERAL PntHTDCO OFFICE. CONTENTS. Page. PREFACE — DIVISIONS OF CATALOGUE ra-vm CATALOGUE 1-69 INDEX 71-79 APPENDIX— I Maps and Charts 81-88 II Chinese Works 84-85 ADDENDA 8C ERRATA ibid PREFACE. ♦ Owing to the want of a complete Catalogue, the Library of the North-China Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society has been hitherto practically inaccessible to the Public. The few students and savants — who were obliged to have recourse to it for their researches — had only for guides the somewhat meagre list of Books and Charts printed in the Council's Report for the year 1865, the manuscript list of the books forming the collection of Mr. Wylie and the memory of the Librarian. This Catalogue will show the poverty of the Library and probably induce public-spirited men to add to its value by presenting works which they may have thought of no interest or already in the collection. Libraries begin to make real progress only when their contents are well known and their object well determined. Mr. Wy lie's Library1 served as the nucleus of a good series of works on China ; and its 718 volumes or pamphlets, added to those already in the possession of the Asiatic Society, formed a collection of standard works on the East numbering about 1,300 volumes2 However valuable this collection may be, its deficiency is very great ; and many a volume which an Orientalist ought to find is sought in vain through the pages of the Catalogue. -

1 Art Architecture & Art of the Book

ART ARCHITECTURE & ART OF THE BOOK sl. stained, corners and head and tail of spine sl. bumped, in worn and rubbed slipcase repaired in parts with selotape. £150.00 1. (Album). THE “LONDON” CIGARETTE CARD 6. (Bach). Williams, Peter. THE ORGAN MUSIC OF J.S. ALBUM. 986 cards in total. ... c.[1930s]. BACH. I Preludes, Toccatas, Fantasias, Fugues, Sonatas, Sm. thick Landscape 4to. Enclosed in album. Sl. shaken, textured Concertos and Miscellaneous Pieces (BWV 525-598, 802-805 buckram boards with gilt title to upper board, some minor soiling etc.). II Works based on Chorales (BWV 599-771 etc). III. A and rubbing. £200.00 Background. CUP 1980-84. 21 complete sets: 1. The Seashore, 50 colour cards, Wills. 2. Garden 1st Ed. 3 vols. Many musical examples, 2 maps. Ex.-libris Hints, 50 colour cards, Wills. 3. Feathered Friends, 25 colour cards, Malcolm Boyd with several marginal pencil annotations, good in Abdulla & Co. Ltd. 4. British Butterflies, 25 colour cards, Abdulla & Co. lightly browned and sl. chipped d/ws. £100.00 Ltd. 5. Interesting Door Knockers, 25 colour cards, Churchman’s. 6. History of Aviation, 25 sepia cards, Lambert & Butler. 7. The King’s Cambridge Studies in Music. Coronation, 50 colour cards, Godfrey Phillips Ltd. 8. Household Hints, Ex.-libris Malcolm Boyd, ex U.C. Wales, Cardiff and acknowledged Bach 50 colour cards, Wills. 9. Links with the Past, 25 b/w. cards, Nicholas expert (several books published including Bach in the ‘Master Musicians’ Series). Sarony & Co. 10. Figures of Speech, 50 colour cards, Ardath Tobacco Co. Ltd. 11. -

Sinologists As Translators in the 17-19Th Century Conference

Sinologists as Translators in the 17-19th century Conference An International Conference Organized by Research Centre for Translation, Institute of Chinese Studies, The Chinese University of Hong Kong On 27—28 October 2011 In Celebration of The Fortieth Anniversary of the Research Centre for Translation Organized by the Research Centre for Translation, Institute of Chinese Studies, The Chinese Uniersity of Hong Kong Sponsored by Institute of Chinese Studies and Chung Chi College, The Chinese University of Hong Kong Research Centre for Translation • Institute of Chinese Studies • The Chinese University of Hong Kong www.cuhk.edu.hk/rct • Tel: (852) 3943 7399 • Fax: (852) 2603 5110 Sinologists as Translators in the 17-19th century Conference 27-28 October, 2011 The Chinese University of Hong Kong Conference Programme Day 1 • 27 October 2011 • Thursday 9:15 – 9:30 Registration 9:30 – 10:00 Opening Introducing RCT+Group photo 10:00 – 10:40 August Pfizmaier (1808-1849) and his Translations of Chinese Poetry Chair: Lawrence Wang-chi Wong Bernhard Fuehrer (University of London) 10:45 – 11:00 Tea break 11:00 – 11:40 The German Rendition of Huajian ji by Heinrich Kurz (Das Blumenblatt, 1836): Translation or Retranslation? Chair: Theodore Huters Roland Altenburger (The University of Zürich) 11:45 – 12:25 Early Translations of Chinese Literature from Chinese into German – The Example of Wilhelm Grube (1855-1908) and Chair: His Translation of Investiture of the Gods 封神演義 Theodore Huters Thomas Zimmer (University of Cologne) 12:30 – 14:00 14:00 – 14:40 -

Smoky Horizons T2

SMOKY HORIZONS TOBACCO AND EMPIRE IN ASIA, 1850-2000 by ASIA PUBLIC HISTORY FOUNDATION September 2020 Abstract Few have attempted to study the introduction and spread of tobacco cultivation in Asia using an analytical frame, which integrates the imperial economy, local social structures, and the commodity history of tobacco. This is a report on preliminary archival and ethnographic work on the economic and social relationship between tobacco cultivation and imperial expansion in Asia, focusing primarily on British India (today’s nation-states of India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh), China, and Japan. It argues (a) that the East India Company (1813-1858) and private European companies (1860-1920) shaped the cultivation and flow of tobacco in Asia by the circulation of capital between British India and Qing China; and (b) that patterns of landholding and moneylending instituted during colonial rule remain dominant for tobacco cultivators in India today. Over a period of six months (April-October 2019), intensive archival research was conducted in London, Bristol, New Delhi, Kolkata, Beijing, Kunming, Kyoto, and Tokyo, and ethnographic interviews were conducted in Yunnan, China and Ranchi, India. Our preliminary findings detailed in this report suggest that the introduction and spread of tobacco cultivation in British India was deeply tied to the imperial economy – particularly the triangular trade on opium between Britain, India, and China. The social relations of debtor and creditor, and landlord and peasant established during British rule remain largely unchanged in the Indian subcontinent. The ethno-historical understanding provides a critical window into the present-day tobacco landscape in India and thus, to study or to transform, it is crucial that one understands the complex relationship of the state and the cultivators, and chronicles its change over time. -

Content Focus 1: from British Administration to HKSAR – Main Features of British Administration in the First Half of the 20 Ce

History (S4-5) Theme A: Modernization and Transformation of Twentieth-Century Asia Sub-theme a: Growth and Development of Hong Kong Content Focus 1: From British administration to HKSAR – main features of British administration in the first half of the 20th century To understand the topic, teachers are recommended to read the following sources: z Cheng Ming ed., Hong Kong Government and Politics (Hong Kong: Oxford University Press, 2003). (English only) z Study Guide on Hong Kong Government and Politics (online), http://www.hku.hk/hkcsp/ccex/text/studyguide/hkpolitics/2_1.html (English only) z Steve Tsang ed., Government and Politics (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press,1995). (English only) z Ho Pui-yan, The Administrative History of the Hong Kong Government Agencies, 1841-2002 (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2004). (English only) z Study Guide on Hong Kong: A Reader in Social History (online), http://www.hku.hk/hkcsp/ccex/text/studyguide/hkhist/unit1.htm (English only) z Peter Harris, Hong Kong: A Study in Bureaucracy and Politics (Hong Kong: Macmillian Publishers (HK) Ltd, 1988). z David Akers-Jones, Feeling the Stones: Reminiscences By David Akers-Jones (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2004). 1 History (S4-5) Theme A: Modernization and Transformation of Twentieth-Century Asia Sub-theme a: Growth and Development of Hong Kong Study Sources A, B and C carefully. Source A The following pictures show the Government House located in Central in 2003. The Government House was formerly the office and residence of previous Governors of Hong Kong. It was then used as the military headquarters for the Japanese until 1945.