The Impact of Anglo-Chinese Relations on the Development of British Liberalism, 1842-1857

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Michael Polanyi and Early Neoliberalism

MICHAEL POLANYI AND EARLY NEOLIBERALISM Martin Beddeleem Keywords: Friedrich Hayek, Louis Rougier, Michael Polanyi, Mont-Pèlerin Society, neoliberalism, planning, Walter Lippmann ABSTRACT1 Between the late 1930s and the 1950s, Michael Polanyi came in close contact with a diverse cast of intellectuals seeking a renewal of the liberal doctrine. The elaboration of this “neoliberalism” happened through a transnational collaboration between economists, philosophers, and social theorists, united in their rejection of central planning. Defining a common agenda for this “early neoliberalism” offered an opportunity to discard the old laissez-faire doctrine and restore a supervisory role of the state. Ultimately, post-war dissensions regarding the direction of these efforts led Polanyi away from the neoliberal core. Between the publication of his pamphlet on the failures of economic planning in the Soviet Union in 1936 (CF, 61-95) and that of The Logic of Liberty in 1951, Michael Polanyi progressively lost interest in chemistry and started to investigate the political and sociological conditions necessary to scientific freedom and the pursuit of truth. During that time, he became involved with a group of scholars who, equally, perceived the democratic collapse of Europe as a wake-up call for a restatement of its liberal tradition. Whereas the values of individual dignity and social progress that liber- alism carried were needed then more than ever, they agreed that the method to achieve these ideals had become obsolete. Therefore, they focused their efforts on revamping a science of liberalism, which could answer the scientific claims of plannism and totalitar- ian ideologies. Tradition & Discovery: The Journal of the Polanyi Society 45:3 © 2019 by the Polanyi Society 31 For two decades, Michael Polanyi took part in the inception and the consolida- tion of “early neoliberalism” (Schulz-Forberg 2018; Beddeleem 2019), a period that predates the later development of neoliberalism from the 1960s onwards. -

David Urquhart's Holy

Click here for Full Issue of EIR Volume 26, Number 36, September 10, 1999 I. The History of Britain’s ‘Great Game’ in Caucasus, Central Asia David Urquhart’s holy war by Joseph Brewda and Linda de Hoyos In 1785, a Chechen leader, Naqshbandi Sufi Sheikh Mansur, services who was touring the Caucasus, wrote in his memoirs raised the Chechen, Ingush, Ossetes, Kabard, Circassian, that “a Circassian prince pointed out [to me] the sacred spot and Dagestani tribes in revolt against the steady advance of (as they justly esteem it) where Daud Bey had held (just the Russian Empire into the Caucasus Mountains. Before three years ago) his meeting with the chieftains of this neigh- 1774, the Caucasus and Transcaucasus region, now embrac- borhood, and first inspired them with the idea of combining ing Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia, had been loosely themselves with the other inhabitants of the mountain prov- ruled by the Persian and Ottoman empires. After Russia’s inces as a nation, under one government and standard.” Daud victory over the Ottoman Empire in the war of 1768-74, the Bey had penned the declaration of independence of Circassia Russian military moved in on the Caucasus. Sheikh Mansur and designed its flag. raised the flag of the “Mountain Peoples” against the czar. Daud Bey was not a native of the Caucasus either. His Although Mansur’s 20,000-man force was crushed by the name was David Urquhart, and he had been sent into the Russian onslaught in 1791, Sheikh Mansur became the hero region on a special mission in 1834 by British intelligence. -

“Bad” Greed from the Enlightenment to Thorstein Veblen (1857-1929)1 Erik S

real-world economics review, issue no. 63 subscribe for free Civilizing capitalism: “good” and “bad” greed from the enlightenment to Thorstein Veblen (1857-1929)1 Erik S. Reinert [Tallinn University of Technology, Estonia and Norway] Copyright: Erik S. Reinert, 2013 You may post comments on this paper at http://rwer.wordpress.com/2013/03/25/rwer-issue-63/ As we look over the country today we see two classes of people. The excessively rich and the abject poor, and between them is a gulf ever deepening, ever widening, and the ranks of the poor are continually being recruited from a third class, the well-to-do, which class is rapidly disappearing and being absorbed by the very poor. Milford Wriarson Howard (1862-1937), in The American Plutocracy, 1895. This paper argues for important similarities between today’s economic situation and the picture painted above by Milford Howard, a member of the US Senate at the time he wrote The American Plutocracy. This was the time, the 1880s and 1890s, when a combination of Manchester Liberalism – a logical extension of Ricardian economics – and Social Darwinism – promoted by the exceedingly influential UK philosopher Herbert Spencer – threatened completely to take over economic thought and policy on both sides of the Atlantic. At the same time, the latter half of the 19th century was marred by financial crises and social unrest. The national cycles of boom and bust were not as globally synchronized as they later became, but they were frequent both in Europe and in the United States. Activist reformer Ida Tarbell probably exaggerated when she recalled that in the US “the eighties dripped with blood”, but a growing gulf between a small and opulent group of bankers and industrialists produced social unrest and bloody labour struggles. -

Uncommon Books, Ephemera & Other Works on Paper

Uncommon Books, Ephemera & other works on Paper Asia Bookroom www.AsiaBookroom.com Page 1 Why Include Asian Material in Your Collection? Librarians and collectors are increasingly adding Asian materials to their collections with the aim of providing a more balanced resource that better reflects the world. Including an Asian perspective on a subject within your collection provides an interesting contrast to the more commonly collected Western focused themes and in doing so provides deeper insights into a world that scholars and collectors were frequently previously unaware of. If you might be interested in pursuing this direction Sally Burdon from Asia Bookroom can advise you. Sally has worked with libraries and collectors worldwide and would welcome the opportunity to discuss your collecting interests. Her business Asia Bookroom specialises exclusively in books, ephemera and other materials on paper with an Asian focus. Asia Bookroom Lawry Place We issue many specialised lists by email. Macquarie ACT 2614 Australia Join our mailing list. Ph: +61 2 6251 5191 Fax: +61 2 6251 5536 Email us on [email protected] or Website: www.AsiaBookroom.com visit our website www.AsiaBookroom.com Email: [email protected] Japan & Korea—19th Century Map With Somewhat Quirky English Captions 樺井達之輔 Kabai Tatsunosuke (Editor) 明治改正 大日本精圖 Meiji kaisei dainihon seizu Detailed Map of Great Japan: Revision in Meiji. Folding map measures 70 x 70.5cm a few small closed tears along folds, 3 small holes at folds with only tiny loss. A very nice map in good condition. Nakamura Asakichi 中 村淺吉 Kyoto. 1887. Coloured copperplate map of Japan with Hokkaido and Korea shown in vignettes at the upper left corner and Okinawa (Ryūkyū) and the Ogasawara Islands in vignettes in the upper middle section of the map in the middle and to the right are the Eastern and Western hemispheres. -

Imperial China and the West Part I, 1815–1881

China and the Modern World: Imperial China and the West Part I, 1815–1881 The East India Company’s steamship Nemesis and other British ships engaging Chinese junks in the Second Battle of Chuenpi, 7 January 1841, during the first opium war. (British Library) ABOUT THE ARCHIVE China and the Modern World: Imperial China and the West Part I, 1815–1881 is digitised from the FO 17 series of British Foreign Office Files—Foreign Office: Political and Other Departments: General Correspondence before 1906, China— held at the National Archives, UK, providing a vast and significant primary source for researching every aspect of Chinese-British relations during the nineteenth century, ranging from diplomacy to trade, economics, politics, warfare, emigration, translation and law. This first part includes all content from FO 17 volumes 1–872. Source Library Number of Images The National Archives, UK Approximately 532,000 CONTENT From Lord Amherst’s mission at the start of the nineteenth century, through the trading monopoly of the Canton System, and the Opium Wars of 1839–1842 and 1856–1860, Britain and other foreign powers gradually gained commercial, legal, and territorial rights in China. Imperial China and the West provides correspondence from the Factories of Canton (modern Guangzhou) and from the missionaries and diplomats who entered China in the early nineteenth century, as well as from the envoys and missions sent to China from Britain and the later legation and consulates. The documents comprising this collection include communications to and from the British legation, first at Hong Kong and later at Peking, and British consuls at Shanghai, Amoy (Xiamen), Swatow (Shantou), Hankow (Hankou), Newchwang (Yingkou), Chefoo (Yantai), Formosa (Taiwan), and more. -

Manchester Group of the Victorian Society Newsletter Spring 2021

MANCHESTER GROUP OF THE VICTORIAN SOCIETY NEWSLETTER SPRING 2021 WELCOME The views expressed within Welcome to the Spring 2021 edition of the Newsletter. this publication are those of the authors concerned and Covid 19 continues to seriously affect the scope of our activities, including the not necessarily those of the cancellation of the Annual General Meeting scheduled for January 2021. This edition of Manchester Group of the the newsletter thus contains details of the matters which would normally have formed Victorian Society. part of the AGM including a brief report from Anne Hodgson, Mark Watson’s Annual Report on Historic Buildings and a statement of accounts for 2020. © Please note that articles published in this newsletter Hopefully, recovery might be in sight. A tour of Oldham Town Centre has been organised are copyright and may not be for Thursday 22 July 2021 at 2.00pm. It is being led by Steve Roman for Manchester reproduced in any form Region Industrial Archaeology Society (MRIAS) and is a shorter version of his walk for without the consent of the the Manchester VicSoc group in June 2019. The walk is free. See page 19 for full details. author concerned. CONTENTS 2 EDGAR WOOD AND THE BRIAR ROSE MOTIF 5 WALTER BRIERLEY AT NEWTON-LE-WILLOWS 7 HIGHFIELDS, HUDDERSFIELD – ‘A MOST HANDSOME SUBURB’ 8 NEW BOOKS: SIR EDWARD WATKIN MP, VICTORIA’S RAILWAY KING 10 THE LIGHTNING EXPRESS – HIGH SPEED RAIL 13 THE LODGES AT LONGFORD PARK 15 “THE SECRET GARDEN:” FRANCES HODGSON BURNETT 19 WALKING TOUR OF OLDHAM TOWN CENTRE 20 MANCHESTER GROUP MATTERS Report by the Chair,. -

Sir Edward Watkin and the Liberal Cause in the Nineteenth Century

Edward William Watkin, born in Salford, Lancashire in 1819, was an exact contemporary of Queen Victoria; he exemplified the Victorian spirit of global awareness, pride in a British civilisation with the intention of sharing its benefits with others, and the excitement of participating in the development of new technology and scientific advancement. John Greaves examines his life. SiR EdWARD WATKIN AND THE LIBERAL CAUSE IN THE NiNETEENTH CENTURY dward William Because of his success in the Corn Laws – the imposition of Watkin, born in Sal- sphere of railways, he was seen tariffs on corn imports to pro- ford, Lancashire in as having a sound grasp of the tect or benefit sectional interests, 1819, was an exact financing and administration which was creating great hard- contempor a r y of of the new engineering and ship for the poor. The organis- EQueen Victoria; he exempli- commercial projects of the day. ing of a free trade campaign was fied the Victorian spirit of glo- In particular his thinking was to give rise to a new political bal awareness, pride in a British informed by the emergence of party, inspired by Christian ide- civilisation with the intention the world’s first industrial city, als of fairness and compassion.1 of sharing its benefits with oth- Manchester, and by the first Watkin was one of those who ers, and the excitement of par- wholesale application of Adam quickly grasped the econom- ticipating in the development of Smith’s theory of free market ics of the capitalist system, and new technology and scientific Edward Watkin capitalism. -

Part 7: Invasions, Rebellions, and the End of Imperial China Part 7 Introduction Pre-Modern Vs

Part 7: Invasions, Rebellions, and the End of Imperial China Part 7 Introduction Pre-modern vs. Modern When does modern Chinese history begin? Some say during the Opium War, the late 1830s and 1840s. Others date modern history from 1919 and the May Fourth Movement. In this course we take the 18th century, when the Qing was at its height, to begin modern Chinese history. Considering that modern history bears some relation to the present, what events signified the beginning of that period? In Europe, historians often chose 1789, the French Revolution. The signifying events, the transitional events, for China begin with its transition from empire to nation-state, with population growth, with the inclusion of Xinjiang and Tibet during the Qianlong reign, and with the challenges of maintaining unity in a multi-ethnic population. Encounter with the West In the 19th century this evolving state ran head-on into the mobile, militarized nation of Great Britain, the likes of which it has never seen before. This encounter was nothing like the visits from Jesuit missionaries (footnote 129 on page 208) or Lord Macartney (page 253). It challenged all the principles of imperial rule. Foreign Enterprise Today’s Chinese economy has its roots in the Sino-foreign enterprises born during these early encounters. Opium was one of its main enterprises. Christianity was a kind of enterprise. These enterprises combined to weaken and humiliate the Qing. As would be said of a later time, these foreign insults were a “disease of the skin.”165 It was the Taiping Rebellion that struck at the heart. -

841D211f0b4bb19c93c26e63b9

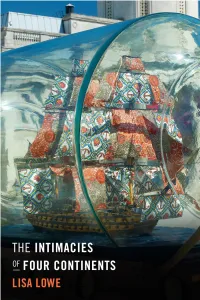

THE INTIMACIES OF FOUR CONTINENTS This page intentionally left blank THE INTIMACIES OF FOUR CONTINENTS LISA LOWE Duke University Press Durham and London 2015 © 2015 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid-f ree paper ∞ Typeset in Minion Pro by Westchester Publishing Services Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Lowe, Lisa. Te intimacies of four continents / Lisa Lowe. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 978-0-8223-5863-3 (hardcover : alk. paper) isbn 978-0-8223-5875-6 (pbk. : alk. paper) isbn 978-0-8223-7564-7 (e- book) 1. Liberalism. 2. Liberty. 3. Slave trade. 4. Commerce. 5. Civilization, Modern. i. Title. jc574.l688 2015 320.51— dc23 2014046258 Cover art: Nelson’s Ship in a Bottle, © Yinka Shonibare mbe. All rights reserved, dAcs/ ars, NY 2014. Photo courtesy Stephen Friedman Gallery, London, and National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, UK. for Juliet This page intentionally left blank CONTENTS CHAPTER 1. THE INTIMACIES OF FOUR CONTINENTS * 1 CHAPTER 2. AUTOBIOGRAPHY OUT OF EMPIRE * 43 CHAPTER 3. A FETISHISM OF COLONIAL COMMODITIES * 73 CHAPTER 4. THE RUSES OF LIBERTY * 101 CHAPTER 5. FREEDOMS YET TO COME * 135 AC KNOW L EDG MENTS * 177 NOTES * 181 REFERENCES * 269 INDEX * 305 1.1 Cutting Sugar Cane in Trinidad, Richard Bridgens (1836). Lithograph from West India Scenery, by Richard Bridgens. © Te British Library Board. CHAPTER 1 THE INTIMACIES OF FOUR CONTINENTS My study investigates the ofen obscured connections between the emer- gence of Eur o pean liberalism, settler colonialism in the Americas, the transatlantic African slave trade, and the East Indies and China trades in the late eigh teenth and early nineteenth centuries. -

Ja Hobson's Approach to International Relations

J.A. HOBSON'S APPROACH TO INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS: AN EXPOSITION AND CRITIQUE David Long Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor Of Philosophy in International Relations at the London School of Economics. UMI Number: U042878 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Disscrrlation Publishing UMI U042878 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Abstract This thesis argues that Hobson’s approach to international relations coheres around his use of the biological analogy of society to an organism. An aspect of this ‘organic analogy’ - the theory of surplus value - is central to Hobson’s modification of liberal thinking on international relations and his reformulated ‘new liberal internationalism’. The first part outlines a theoretical framework for Hobson’s discussion of international relations. His theory of surplus value posits cooperation as a factor in the production of value understood as human welfare. The organic analogy links this theory of surplus value to Hobson’s holistic ‘sociology’. Hobson’s new liberal internationalism is an extension of his organic theory of surplus value. -

Interaction and Social Complexity in Lingnan During the First Millennium B.C

Interaction and Social Complexity in Lingnan during the First Millennium B.C. FRANCIS ALLARD SEPARATED FROM AREAS north of it by mountain ranges and drained by a single river system, the region of Lingnan in southeastern China is a distinct physio graphic province (Fig. 1). The home of historically recorded tribes, it was not until the late first millennium B.C. that Lingnan was incorporated into the ex panding Chinese polities of central and northern China. The Qin, Han, and probably the Chu before them not only knew of those they called barbarians in southeastern China but also pursued an expansionary policy that would help es tablish the boundaries of the modem Chinese state in later times. The first millennium B.C. in Lingnan witnessed the development of a bronze metallurgy and its subsequent widespread use by the seventh or sixth centuries B.C. Archaeological work over the last decades has led to the discovery of a num ber ofBronze Age burials scattered over much of northern Lingnan and dating to approximately 600 to 200 B.C., a period covering the middle-late Spring and Autumn period and all of the Warring States period (Fig. 2). These important discoveries have helped establish the region as the theater for the emergence of social complexity before the arrival of the Qin and Han dynasties in Lingnan. Nevertheless, and in keeping with traditional models of interpretation, Chinese archaeologists have tried to understand this material in the context of contact with those expanding states located to the north of Lingnan. The elaborate ma terial culture and complex political structures associated with these states has usually meant that change in those so-called peripheral areas (including Lingnan) could only be the result of cultural diffusion from the center. -

China's New Social Governance

China’s New Social Governance Ketty A. Loeb A dissertation Submitted in partial fulfilment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2014 Reading Committee: David Bachman, Chair Tony Gill Karen Litfin Mary Kay Gugerty Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Department of Political Science © Copyright 2014 Ketty A. Loeb University of Washington Abstract China’s New Social Governance Ketty A. Loeb Chair of Supervisory Committee: Professor David Bachman Jackson School of International Studies This dissertation explores the sources and mechanisms of social policy change in China during the reform era. In it, I first argue that, starting in the late 1990s, China’s leadership began shifting social policy away from the neoliberal approach that characterized the first two decades of the reform era towards a New Governance approach. Second, I ask the question why this policy transformation is taking place. I employ a political economy argument to answer this question, which locates the source of China’s New Governance transition in diversifying societal demand for public goods provision. China’s leadership is concerned about the destabilizing impacts of this social transformation, and has embraced the decentralized tools of New Governance in order to improve responsiveness and short up its own legitimacy. Third, I address how China’s leadership is undertaking this policy shift. I argue that China’s version of New Governance is being undertaken in such as way as to protect the Chinese Communist Party’s monopoly over power. This double-edged strategy is aimed at improving the capacity consists of Social Construction, on the one hand, and Social Management Innovation, on the other.