CO129 and Hong Kong's History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Guangzhou-Hongkong Strike, 1925-1926

The Guangzhou-Hongkong Strike, 1925-1926 Hongkong Workers in an Anti-Imperialist Movement Robert JamesHorrocks Submitted in accordancewith the requirementsfor the degreeof PhD The University of Leeds Departmentof East Asian Studies October 1994 The candidateconfirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where referencehas been made to the work of others. 11 Abstract In this thesis, I study the Guangzhou-Hongkong strike of 1925-1926. My analysis differs from past studies' suggestions that the strike was a libertarian eruption of mass protest against British imperialism and the Hongkong Government, which, according to these studies, exploited and oppressed Chinese in Guangdong and Hongkong. I argue that a political party, the CCP, led, organised, and nurtured the strike. It centralised political power in its hands and tried to impose its revolutionary visions on those under its control. First, I describe how foreign trade enriched many people outside the state. I go on to describe how Chinese-run institutions governed Hongkong's increasingly settled non-elite Chinese population. I reject ideas that Hongkong's mixed-class unions exploited workers and suggest that revolutionaries failed to transform Hongkong society either before or during the strike. My thesis shows that the strike bureaucracy was an authoritarian power structure; the strike's unprecedented political demands reflected the CCP's revolutionary political platform, which was sometimes incompatible with the interests of Hongkong's unions. I suggestthat the revolutionary elite's goals were not identical to those of the unions it claimed to represent: Hongkong unions preserved their autonomy in the face of revolutionaries' attempts to control Hongkong workers. -

H.Doc. 108-224 Black Americans in Congress 1870-2007

“The Negroes’ Temporary Farewell” JIM CROW AND THE EXCLUSION OF AFRICAN AMERICANS FROM CONGRESS, 1887–1929 On December 5, 1887, for the first time in almost two decades, Congress convened without an African-American Member. “All the men who stood up in awkward squads to be sworn in on Monday had white faces,” noted a correspondent for the Philadelphia Record of the Members who took the oath of office on the House Floor. “The negro is not only out of Congress, he is practically out of politics.”1 Though three black men served in the next Congress (51st, 1889–1891), the number of African Americans serving on Capitol Hill diminished significantly as the congressional focus on racial equality faded. Only five African Americans were elected to the House in the next decade: Henry Cheatham and George White of North Carolina, Thomas Miller and George Murray of South Carolina, and John M. Langston of Virginia. But despite their isolation, these men sought to represent the interests of all African Americans. Like their predecessors, they confronted violent and contested elections, difficulty procuring desirable committee assignments, and an inability to pass their legislative initiatives. Moreover, these black Members faced further impediments in the form of legalized segregation and disfranchisement, general disinterest in progressive racial legislation, and the increasing power of southern conservatives in Congress. John M. Langston took his seat in Congress after contesting the election results in his district. One of the first African Americans in the nation elected to public office, he was clerk of the Brownhelm (Ohio) Townshipn i 1855. -

Macmillan History 9

Chapter 5 Making a nation HISTORY SKILLS In this chapter you will learn to apply the following historical skills: • explain the effects of contact on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, categorising these effects as either intended or unintended • outline the migration of Chinese to the goldfields in Australia in the 19th century and attitudes towards the Chinese, as revealed in cartoons • identify the main features of housing, sanitation, transport, education and industry that influenced living and working conditions in Australia • describe the impact of the gold rushes (hinterland) on the development of ‘Marvellous Melbourne’ • explain the factors that contributed to federation and the development of democracy in Australia, including defence concerns, the 1890s depression, nationalist ideals, egalitarianism and the Westminster system • investigate how the major social legislation of the new federal government—for example, invalid and old-age pensions and the maternity allowance scheme—affected living and working conditions in Australia. © Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority 2012 Federation celebrations in Centennial Park, Sydney, 1 January 1901 Inquiry questions 1 What were the effects of contact between European 4 What were the key events and ideas in the settlers in Australia and Aboriginal and Torres Strait development of Australian self-government and IslanderSAMPLE peoples when settlement extended? democracy? 2 What were the experiences of non-Europeans in 5 What significant legislation was passed in the Australia prior to the 1900s? period 1901–1914? 3 What were the living and working conditions in Australia around 1900? Introduction THE EXPERIENCE OF indigenous peoples, Europeans and non-Europeans in 19th-century Australia were very different. -

Chapter 2 Music in the United States Before the Great Depression

American Music in the 20th Century 6 Chapter 2 Music in the United States Before the Great Depression Background: The United States in 1900-1929 In 1920 in the US - Average annual income = $1,100 - Average purchase price of a house = $4,000 - A year's tuition at Harvard University = $200 - Average price of a car = $600 - A gallon of gas = 20 cents - A loaf of Bread = 20 cents Between 1900 and the October 1929 stock market crash that triggered the Great Depression, the United States population grew By 47 million citizens (from 76 million to 123 million). Guided by the vision of presidents Theodore Roosevelt1 and William Taft,2 the US 1) began exerting greater political influence in North America and the Caribbean.3 2) completed the Panama Canal4—making it much faster and cheaper to ship its goods around the world. 3) entered its "Progressive Era" by a) passing anti-trust laws to Break up corporate monopolies, b) abolishing child labor in favor of federally-funded puBlic education, and c) initiating the first federal oversight of food and drug quality. 4) grew to 48 states coast-to-coast (1912). 5) ratified the 16th Amendment—estaBlishing a federal income tax (1913). In addition, by 1901, the Lucas brothers had developed a reliaBle process to extract crude oil from underground, which soon massively increased the worldwide supply of oil while significantly lowering its price. This turned the US into the leader of the new energy technology for the next 60 years, and opened the possibility for numerous new oil-reliant inventions. -

Uncommon Books, Ephemera & Other Works on Paper

Uncommon Books, Ephemera & other works on Paper Asia Bookroom www.AsiaBookroom.com Page 1 Why Include Asian Material in Your Collection? Librarians and collectors are increasingly adding Asian materials to their collections with the aim of providing a more balanced resource that better reflects the world. Including an Asian perspective on a subject within your collection provides an interesting contrast to the more commonly collected Western focused themes and in doing so provides deeper insights into a world that scholars and collectors were frequently previously unaware of. If you might be interested in pursuing this direction Sally Burdon from Asia Bookroom can advise you. Sally has worked with libraries and collectors worldwide and would welcome the opportunity to discuss your collecting interests. Her business Asia Bookroom specialises exclusively in books, ephemera and other materials on paper with an Asian focus. Asia Bookroom Lawry Place We issue many specialised lists by email. Macquarie ACT 2614 Australia Join our mailing list. Ph: +61 2 6251 5191 Fax: +61 2 6251 5536 Email us on [email protected] or Website: www.AsiaBookroom.com visit our website www.AsiaBookroom.com Email: [email protected] Japan & Korea—19th Century Map With Somewhat Quirky English Captions 樺井達之輔 Kabai Tatsunosuke (Editor) 明治改正 大日本精圖 Meiji kaisei dainihon seizu Detailed Map of Great Japan: Revision in Meiji. Folding map measures 70 x 70.5cm a few small closed tears along folds, 3 small holes at folds with only tiny loss. A very nice map in good condition. Nakamura Asakichi 中 村淺吉 Kyoto. 1887. Coloured copperplate map of Japan with Hokkaido and Korea shown in vignettes at the upper left corner and Okinawa (Ryūkyū) and the Ogasawara Islands in vignettes in the upper middle section of the map in the middle and to the right are the Eastern and Western hemispheres. -

Enfry Denied Aslan American History and Culture

In &a r*tm Enfry Denied Aslan American History and Culture edited by Sucheng Chan Exclusion and the Chinese Communify in America, r88z-ry43 Edited by Sucheng Chan Also in the series: Gary Y. Okihiro, Cane Fires: The Anti-lapanese Moaement Temple University press in Hawaii, t855-ry45 Philadelphia Chapter 6 The Kuomintang in Chinese American Kuomintang in Chinese American Communities 477 E Communities before World War II the party in the Chinese American communities as they reflected events and changes in the party's ideology in China. The Chinese during the Exclusion Era The Chinese became victims of American racism after they arrived in Him Lai Mark California in large numbers during the mid nineteenth century. Even while their labor was exploited for developing the resources of the West, they were targets of discriminatory legislation, physical attacks, and mob violence. Assigned the role of scapegoats, they were blamed for society's multitude of social and economic ills. A populist anti-Chinese movement ultimately pressured the U.S. Congress to pass the first Chinese exclusion act in 1882. Racial discrimination, however, was not limited to incoming immi- grants. The established Chinese community itself came under attack as The Chinese settled in California in the mid nineteenth white America showed by words and deeds that it considered the Chinese century and quickly became an important component in the pariahs. Attacked by demagogues and opportunistic politicians at will, state's economy. However, they also encountered anti- Chinese were victimizedby criminal elements as well. They were even- Chinese sentiments, which culminated in the enactment of tually squeezed out of practically all but the most menial occupations in the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. -

841D211f0b4bb19c93c26e63b9

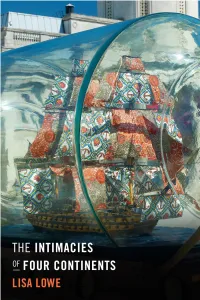

THE INTIMACIES OF FOUR CONTINENTS This page intentionally left blank THE INTIMACIES OF FOUR CONTINENTS LISA LOWE Duke University Press Durham and London 2015 © 2015 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid-f ree paper ∞ Typeset in Minion Pro by Westchester Publishing Services Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Lowe, Lisa. Te intimacies of four continents / Lisa Lowe. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 978-0-8223-5863-3 (hardcover : alk. paper) isbn 978-0-8223-5875-6 (pbk. : alk. paper) isbn 978-0-8223-7564-7 (e- book) 1. Liberalism. 2. Liberty. 3. Slave trade. 4. Commerce. 5. Civilization, Modern. i. Title. jc574.l688 2015 320.51— dc23 2014046258 Cover art: Nelson’s Ship in a Bottle, © Yinka Shonibare mbe. All rights reserved, dAcs/ ars, NY 2014. Photo courtesy Stephen Friedman Gallery, London, and National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, UK. for Juliet This page intentionally left blank CONTENTS CHAPTER 1. THE INTIMACIES OF FOUR CONTINENTS * 1 CHAPTER 2. AUTOBIOGRAPHY OUT OF EMPIRE * 43 CHAPTER 3. A FETISHISM OF COLONIAL COMMODITIES * 73 CHAPTER 4. THE RUSES OF LIBERTY * 101 CHAPTER 5. FREEDOMS YET TO COME * 135 AC KNOW L EDG MENTS * 177 NOTES * 181 REFERENCES * 269 INDEX * 305 1.1 Cutting Sugar Cane in Trinidad, Richard Bridgens (1836). Lithograph from West India Scenery, by Richard Bridgens. © Te British Library Board. CHAPTER 1 THE INTIMACIES OF FOUR CONTINENTS My study investigates the ofen obscured connections between the emer- gence of Eur o pean liberalism, settler colonialism in the Americas, the transatlantic African slave trade, and the East Indies and China trades in the late eigh teenth and early nineteenth centuries. -

Urban Forms and the Politics of Property in Colonial Hong Kong By

Speculative Modern: Urban Forms and the Politics of Property in Colonial Hong Kong by Cecilia Louise Chu A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Architecture in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Nezar AlSayyad, Chair Professor C. Greig Crysler Professor Eugene F. Irschick Spring 2012 Speculative Modern: Urban Forms and the Politics of Property in Colonial Hong Kong Copyright 2012 by Cecilia Louise Chu 1 Abstract Speculative Modern: Urban Forms and the Politics of Property in Colonial Hong Kong Cecilia Louise Chu Doctor of Philosophy in Architecture University of California, Berkeley Professor Nezar AlSayyad, Chair This dissertation traces the genealogy of property development and emergence of an urban milieu in Hong Kong between the 1870s and mid 1930s. This is a period that saw the transition of colonial rule from one that relied heavily on coercion to one that was increasingly “civil,” in the sense that a growing number of native Chinese came to willingly abide by, if not whole-heartedly accept, the rules and regulations of the colonial state whilst becoming more assertive in exercising their rights under the rule of law. Long hailed for its laissez-faire credentials and market freedom, Hong Kong offers a unique context to study what I call “speculative urbanism,” wherein the colonial government’s heavy reliance on generating revenue from private property supported a lucrative housing market that enriched a large number of native property owners. Although resenting the discrimination they encountered in the colonial territory, they were able to accumulate economic and social capital by working within and around the colonial regulatory system. -

Discriminatory Zoning in Colonial Hong Kong: a R Eview of the Post-War Literature and Some F Ur Ther Evidence F Or an Economic Theor Y of Discr Imination Abstract

Discriminatory Zoning in Colonial Hong Kong: A r eview of the post-war literature and some f ur ther evidence f or an economic theor y of discr imination Abstract TYPE OF PAPER: RESEARCH PAPER STRUCTURED ABSTRACT Purpose: This paper argues that racially discriminatory zoning in Colonial Hong Kong could have been a form of protectionism driven by economic considerations. Design/Methodology/Approach: This paper was based on a review of the relevant ordinances, literature, and public information, notably data obtained from the Land Registry and telephone directories. Findings: This paper reveals that many writings on racial matters in Hong Kong were not a correct interpretation or presentation of facts. It shows that after the repeal of the discriminatory laws in 1946r, an increasing number of people, both Chinese and European, were living in the Peak district. Besides, Chinese were found to be acquiring land even under the discriminatory law for Barker Road during the mid-1920s and became, after 1946, the majority landlords by the mid-1970s. This testifies to the argument that the Chinese could compete economically with Europeans for prime residential premises in Hong Kong. Research Implications: This paper lends further support to the Lawrence-Marco proposition raised in Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design by Lai and Yu (2001), which regards segregation zoning as a means to reduce the effective demand of an economically resourceful social group. Practical Implications: This paper shows how title documents for land and telephone directories can be used to measure the degree of racial segregation. Originality/Value: This paper is the first attempt to systematically re-interpret English literature on racially discriminatory zoning in Hong Kong’s Peak area using reliable public information from Crown Leases and telephone directories. -

![Normalia [March 1901]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0801/normalia-march-1901-900801.webp)

Normalia [March 1901]

St. Cloud State University theRepository at St. Cloud State Normalia Student Publications 3-1901 Normalia [March 1901] St. Cloud State University Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.stcloudstate.edu/normalia Recommended Citation St. Cloud State University, "Normalia [March 1901]" (1901). Normalia. 80. https://repository.stcloudstate.edu/normalia/80 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Publications at theRepository at St. Cloud State. It has been accepted for inclusion in Normalia by an authorized administrator of theRepository at St. Cloud State. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ~~~ THE ~,~i ormo/1fL r~~~~~~~ l'ift4'ifl lf8®llBUIL4lb l®lltl®®lb, AT ST. CLOUD, _MINN . •••••••• Sustained by the State for the Training of its Teachers. ~ •••••••• COURSES OF STUDY. 1. An Advanced English Course, extending through five years. 2. An Advanced Latin Course, extendin~ through five years. 1. Elementary Course, one year. 3. Graduate Courses 2. Advaneed Course, two years. l3. Kindergarten Course, two years. •••••••• The Diploma. of either course is a State Oertifica.te of qualification of the First Grade good for two years. At the expiration of two years, the Diploma may be en- dorsed, making it a certificate of qualification of the first grade, good for five years if an Elementary diploma, or a Permanent Oertifica.te if an Advanced diploma. The demand for trained teachers in Minncs;ota greatly exceeds the supply. Tbe ~ best of the graduates readily obtain positions at good salaries. ~ ADMISSION. ,:I Graduates of High Schools and Colleges arc admitted to the Grad•atc Courses Cf without examination. -

Forgotten Souls

FORGOTTEN SOULS A SOCIAL HISTORY OF THE HONG KONG CEMETERY PATRICIA LIM Hong Kong University Press The University of Hong Kong Pokfulam Road Hong Kong www.hkupress.org © Hong Kong University Press 2011 First published 2011 Reprinted 2013 ISBN 978-962-209-990-6 All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 Printed and bound by Kings Time Printing Press Ltd., Hong Kong, China Contents Foreword ix Preface xi Introduction: The Hong Kong Cemetery, Its Position and History 1 Section I: An Introduction to Early Hong Kong Chapter 1: The Early Settlers, the First Opium War and Its Aftermath 30 Chapter 2: Events Affecting Hong Kong as They Involved the Lives of People Buried in the Hong Kong Cemetery 59 Chapter 3: How Early Hong Kong Society Arranged Itself 73 Section II: The Early Denizens of the Hong Kong Cemetery, 1845–1860 Chapter 4: Merchants, Clerks and Bankers 92 Chapter 5: Servants of the Crown 113 Chapter 6: Professionals 143 Chapter 7: The Merchant Navy 158 Chapter 8: Tradesmen, Artisans and Small-Scale Businessmen 183 Chapter 9: Beachcombers and Destitutes 211 Chapter 10: Missionaries 214 Chapter 11: The Americans 235 Chapter 12: The Armed Forces 242 Chapter 13: Women and Children -

Mao Zedong's Class Analysis Method and Its Contemporary Value Shuang Li* No

Advances in Intelligent Systems Research, volume 163 8th International Conference on Management, Education and Information (MEICI 2018) Mao Zedong's Class Analysis Method and Its Contemporary Value Shuang Li* No. 232, Wensan road, Xihu district, Hangzhou city, Zhejiang province [email protected] Keywords: Mao Zedong; Class analysis method; Contemporary value Abstract. In the article analysis of social classes in China written by Mao Zedong in 1925, the author combined the Marxist theory of class analysis with the concrete reality of Chinese society, and accurately divided the classes existing in Chinese society at that time, providing useful guidance for the formulation of revolutionary strategies. With the development of Chinese society becoming more and more complex and diversified, Mao Zedong's class analysis is still of great significance. Mao Zedong's thought of class analysis inspires us not to lose the Marxist theory of class analysis; In the new era, we should master the essence of class analysis theory and correctly analyze Chinese social class and class problems. The analysis of ideology should go deep into the class and stratum problems. We should use class analysis to build the Chinese dream of national rejuvenation. Introduce. Since the reform and opening up, China has undergone profound adjustment and reform in its social and economic structure and industrial structure. China's social structure has become increasingly complicated and diversified, and some emerging strata have emerged. How can we properly analyze and grasp this new structure of Chinese society? At the same time, various ideological trends are surging in the ideological field, and people's values are diversified.