Britain's Second Embassy to China

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A St. Helena Who's Who, Or a Directory of the Island During the Captivity of Napoleon

A ST. HELENA WHO'S WHO A ST. HELENA WHO'S WHO ARCHIBALD ARNOTT, M.D. See page si. A ST. HELENA WHO'S WHO OR A DIRECTORY OF THE ISLAND DURING THE CAPTIVITY OF NAPOLEON BY ARNOLD gHAPLIN, M.D. (cantab.) Author of The Illness and Death of Napoleon, Thomas Shortt, etc. NEW YORK E. P. DUTTON AND COMPANY LONDON : ARTHUR L. HUMPHREYS 1919 SECOND EDITION REVISED AND ENLARGED PREFACE The first edition of A St. Helena Whos Wlio was limited to one hundred and fifty copies, for it was felt that the book could appeal only to those who were students of the period of Napoleon's captivity in St. Helena. The author soon found, however, that the edition was insuffi- cient to meet the demand, and he was obliged, with regret, to inform many who desired to possess the book that the issue was exhausted. In the present edition the original form in which the work appeared has been retained, but fresh material has been included, and many corrections have been made which, it is hoped, will render the book more useful. vu CONTENTS PAQI Introduction ....... 1 The Island or St. Helena and its Administration . 7 Military ....... 8 Naval ....... 9 Civil ....... 10 The Population of St. Helena in 1820 . .15 The Expenses of Administration in St. Helena in 1817 15 The Residents at Longwood . .16 Topography— Principal Residences . .19 The Regiments in St. Helena . .22 The 53rd Foot Regiment (2nd Battalion) . 22 The 66th Foot Regiment (2nd Battalion) . 26 The 66th Foot Regiment (1st Battalion) . 29 The 20th Foot Regiment . -

Hwang, Yin (2014) Victory Pictures in a Time of Defeat: Depicting War in the Print and Visual Culture of Late Qing China 1884 ‐ 1901

Hwang, Yin (2014) Victory pictures in a time of defeat: depicting war in the print and visual culture of late Qing China 1884 ‐ 1901. PhD Thesis. SOAS, University of London http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/18449 Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non‐commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this thesis, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", name of the School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination. VICTORY PICTURES IN A TIME OF DEFEAT Depicting War in the Print and Visual Culture of Late Qing China 1884-1901 Yin Hwang Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the History of Art 2014 Department of the History of Art and Archaeology School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London 2 Declaration for PhD thesis I have read and understood regulation 17.9 of the Regulations for students of the School of Oriental and African Studies concerning plagiarism. I undertake that all the material presented for examination is my own work and has not been written for me, in whole or in part, by any other person. -

William T. Rowe

Bao Shichen: An Early Nineteenth-Century Chinese Agrarian Reformer William T. Rowe Johns Hopkins University Prefatory note to the Agrarian Studies Program: I was greatly flattered to receive an invitation from Jim Scott to present to this exalted group, and could not refuse. I’m also a bit embarrassed, however, because I’m not working on anything these days that falls significantly within your arena of interest. I am studying in general a reformist scholar of the early nineteenth century, named Bao Shichen. The contexts in which I have tended to view him (and around which I organized panels for the Association for Asian Studies Annual Meetings in 2007 and 2009) have been (1) the broader reformist currents of his era, spawned by a deepening sense of dynastic crisis after ca. 1800, and (2) an enduring Qing political “counter discourse” beginning in the mid-seventeenth century and continuing down to, and likely through, the Republican Revolution of 1911. Neither of these rubrics are directly concerned with “agrarian studies.” Bao did, however, have quite a bit to say in passing about agriculture, village life, and especially local rural governance. In this paper I have tried to draw together some of this material, but I fear it is as yet none too neat. In my defense, I would add that previously in my career I have done a fair amount of work on what legitimately is agrarian history, and indeed have taught courses on that subject (students are less interested in such offerings now than they used to be, in my observation). -

Uncommon Books, Ephemera & Other Works on Paper

Uncommon Books, Ephemera & other works on Paper Asia Bookroom www.AsiaBookroom.com Page 1 Why Include Asian Material in Your Collection? Librarians and collectors are increasingly adding Asian materials to their collections with the aim of providing a more balanced resource that better reflects the world. Including an Asian perspective on a subject within your collection provides an interesting contrast to the more commonly collected Western focused themes and in doing so provides deeper insights into a world that scholars and collectors were frequently previously unaware of. If you might be interested in pursuing this direction Sally Burdon from Asia Bookroom can advise you. Sally has worked with libraries and collectors worldwide and would welcome the opportunity to discuss your collecting interests. Her business Asia Bookroom specialises exclusively in books, ephemera and other materials on paper with an Asian focus. Asia Bookroom Lawry Place We issue many specialised lists by email. Macquarie ACT 2614 Australia Join our mailing list. Ph: +61 2 6251 5191 Fax: +61 2 6251 5536 Email us on [email protected] or Website: www.AsiaBookroom.com visit our website www.AsiaBookroom.com Email: [email protected] Japan & Korea—19th Century Map With Somewhat Quirky English Captions 樺井達之輔 Kabai Tatsunosuke (Editor) 明治改正 大日本精圖 Meiji kaisei dainihon seizu Detailed Map of Great Japan: Revision in Meiji. Folding map measures 70 x 70.5cm a few small closed tears along folds, 3 small holes at folds with only tiny loss. A very nice map in good condition. Nakamura Asakichi 中 村淺吉 Kyoto. 1887. Coloured copperplate map of Japan with Hokkaido and Korea shown in vignettes at the upper left corner and Okinawa (Ryūkyū) and the Ogasawara Islands in vignettes in the upper middle section of the map in the middle and to the right are the Eastern and Western hemispheres. -

Imperial China and the West Part I, 1815–1881

China and the Modern World: Imperial China and the West Part I, 1815–1881 The East India Company’s steamship Nemesis and other British ships engaging Chinese junks in the Second Battle of Chuenpi, 7 January 1841, during the first opium war. (British Library) ABOUT THE ARCHIVE China and the Modern World: Imperial China and the West Part I, 1815–1881 is digitised from the FO 17 series of British Foreign Office Files—Foreign Office: Political and Other Departments: General Correspondence before 1906, China— held at the National Archives, UK, providing a vast and significant primary source for researching every aspect of Chinese-British relations during the nineteenth century, ranging from diplomacy to trade, economics, politics, warfare, emigration, translation and law. This first part includes all content from FO 17 volumes 1–872. Source Library Number of Images The National Archives, UK Approximately 532,000 CONTENT From Lord Amherst’s mission at the start of the nineteenth century, through the trading monopoly of the Canton System, and the Opium Wars of 1839–1842 and 1856–1860, Britain and other foreign powers gradually gained commercial, legal, and territorial rights in China. Imperial China and the West provides correspondence from the Factories of Canton (modern Guangzhou) and from the missionaries and diplomats who entered China in the early nineteenth century, as well as from the envoys and missions sent to China from Britain and the later legation and consulates. The documents comprising this collection include communications to and from the British legation, first at Hong Kong and later at Peking, and British consuls at Shanghai, Amoy (Xiamen), Swatow (Shantou), Hankow (Hankou), Newchwang (Yingkou), Chefoo (Yantai), Formosa (Taiwan), and more. -

Gift, Greeting Or Gesture: the Khatak and the Negotiating of Its Meaning on the Anglo-Tibetan Borderlands

HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies Volume 35 Number 2 Article 10 January 2016 Gift, Greeting Or Gesture: The Khatak And The Negotiating Of Its Meaning On The Anglo-Tibetan Borderlands Emma Martin National Museums Liverpool / University of Manchester, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya Recommended Citation Martin, Emma. 2016. Gift, Greeting Or Gesture: The Khatak And The Negotiating Of Its Meaning On The Anglo-Tibetan Borderlands. HIMALAYA 35(2). Available at: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya/vol35/iss2/10 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. This Research Article is brought to you for free and open access by the DigitalCommons@Macalester College at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Gift, Greeting Or Gesture: The Khatak And The Negotiating Of Its Meaning On The Anglo-Tibetan Borderlands Acknowledgements Special thanks go to Mr Tashi Tsering, Director of Amnye Machen Institute, Dharamshala, for taking up the challenge and finding the majority of the Tibetan sources noted here. Discussions with him on the biography of the thirteenth Dalai Lama and its lack of reference to documentation or diaries written during the lama’s 1910-12 exile were also invaluable. In addition, thanks to Mr Sonam Tsering, Columbia University for his sensitive translation of the Tibetan sources. Furthermore, the financial support of the Frederick Williamson Memorial Fund, the University of London, Central Research Fund and National Museums Liverpool made possible the doctoral archival research, which, in part, this paper is taken from. -

Houqua and His China Trade Partners in the Nineteenth Century

Global Positioning: Houqua and His China Trade Partners in the Nineteenth Century The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Wong, John. 2012. Global Positioning: Houqua and His China Trade Partners in the Nineteenth Century. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:9282867 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA © 2012 – John D. Wong All rights reserved. Professor Michael Szonyi John D. Wong Global Positioning: Houqua and his China Trade Partners in the Nineteenth Century Abstract This study unearths the lost world of early-nineteenth-century Canton. Known today as Guangzhou, this Chinese city witnessed the economic dynamism of global commerce until the demise of the Canton System in 1842. Records of its commercial vitality and global interactions faded only because we have allowed our image of old Canton to be clouded by China’s weakness beginning in the mid-1800s. By reviving this story of economic vibrancy, I restore the historical contingency at the juncture at which global commercial equilibrium unraveled with the collapse of the Canton system, and reshape our understanding of China’s subsequent economic experience. I explore this story of the China trade that helped shape the modern world through the lens of a single prominent merchant house and its leading figure, Wu Bingjian, known to the West by his trading name of Houqua. -

Chapter 2. the Slender Thread Cast Off: Migration & Reception

The Slender Thread Chapter 2 Willeen Keough Chapter 2 The Slender Thread Cast Off Migration and Reception in Newfoundland When Michael and Mary Ryan were coming from County Wexford Ireland to Nfld. their first child was Born at sea. It was the year 1826. The boy was named Thomas Ryan… Michael Ryan… was drowned near Petty Harbour Motion, in the year 1830 on a sealing voyage. His wife Mary Ryan was left with 3 young children, Thomas who was born at sea, Michael and Thimothy Ryan. After some years Mary Ryan Married again. Edward Coady also a native of County Wexford. They had a family of 2 sons and 1 daughter… They have many decendents at Cape Broyle, many places in Canada and also in the United States. Audio Sample These homespun words, transcribed from the oral tradition by an elderly community historian in 1971, provide a skeletal story of an Irish woman who came to Cape Broyle on the southern Avalon in the early nineteenth century.1 It is a sparse and plainspoken chronicle of her life, but Mary Ryan's story could be the stuff of movie directors' dreams. A young Irish woman leaves her home in Wexford to accompany her husband on a perilous journey that will bring her to a landscape quite different from the green farmlands of her home country. There has been some urgency in their leaving, for Mary is well into her pregnancy upon departure, and the transatlantic crossing, difficult at best, will be a dangerous venture for a woman about to give birth. -

British Major-General Charles George Gordon and His Legacies, 1885-1960 Stephanie Laffer

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2010 Gordon's Ghosts: British Major-General Charles George Gordon and His Legacies, 1885-1960 Stephanie Laffer Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES GORDON‘S GHOSTS: BRITISH MAJOR-GENERAL CHARLES GEORGE GORDON AND HIS LEGACIES, 1885-1960 By STEPHANIE LAFFER A Dissertation submitted to the Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2010 Copyright © 2010 Stephanie Laffer All Rights Reserve The members of the committee approve the dissertation of Stephanie Laffer defended on February 5, 2010. __________________________________ Charles Upchurch Professor Directing Dissertation __________________________________ Barry Faulk University Representative __________________________________ Max Paul Friedman Committee Member __________________________________ Peter Garretson Committee Member __________________________________ Jonathan Grant Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members. ii For my parents, who always encouraged me… iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation has been a multi-year project, with research in multiple states and countries. It would not have been possible without the generous assistance of the libraries and archives I visited, in both the United States and the United Kingdom. However, without the support of the history department and Florida State University, I would not have been able to complete the project. My advisor, Charles Upchurch encouraged me to broaden my understanding of the British Empire, which led to my decision to study Charles Gordon. Dr. Upchurch‘s constant urging for me to push my writing and theoretical understanding of imperialism further, led to a much stronger dissertation than I could have ever produced on my own. -

The Production of Bhutan's Asymmetrical Inbetweenness in Geopolitics Kaul, N

WestminsterResearch http://www.westminster.ac.uk/westminsterresearch 'Where is Bhutan?': The Production of Bhutan's Asymmetrical Inbetweenness in Geopolitics Kaul, N. This journal article has been accepted for publication and will appear in a revised form, subsequent to peer review and/or editorial input by Cambridge University Press in the Journal of Asian Studies. This version is free to view and download for private research and study only. Not for re-distribution, re-sale or use in derivative works. © Cambridge University Press, 2021 The final definitive version in the online edition of the journal article at Cambridge Journals Online is available at: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021911820003691 The WestminsterResearch online digital archive at the University of Westminster aims to make the research output of the University available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the authors and/or copyright owners. Manuscript ‘Where is Bhutan?’: The Production of Bhutan’s Asymmetrical Inbetweenness in Geopolitics Abstract In this paper, I interrogate the exhaustive ‘inbetweenness’ through which Bhutan is understood and located on a map (‘inbetween India and China’), arguing that this naturalizes a contemporary geopolitics with little depth about how this inbetweenness shifted historically over the previous centuries, thereby constructing a timeless, obscure, remote Bhutan which is ‘naturally’ oriented southwards. I provide an account of how Bhutan’s asymmetrical inbetweenness construction is nested in the larger story of the formation and consolidation of imperial British India and its dissolution, and the emergence of post-colonial India as a successor state. I identify and analyze the key economic dynamics of three specific phases (late 18th to mid 19th centuries, mid 19th to early 20th centuries, early 20th century onwards) marked by commercial, production, and security interests, through which this asymmetrical inbetweenness was consolidated. -

841D211f0b4bb19c93c26e63b9

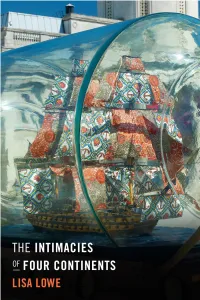

THE INTIMACIES OF FOUR CONTINENTS This page intentionally left blank THE INTIMACIES OF FOUR CONTINENTS LISA LOWE Duke University Press Durham and London 2015 © 2015 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid-f ree paper ∞ Typeset in Minion Pro by Westchester Publishing Services Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Lowe, Lisa. Te intimacies of four continents / Lisa Lowe. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 978-0-8223-5863-3 (hardcover : alk. paper) isbn 978-0-8223-5875-6 (pbk. : alk. paper) isbn 978-0-8223-7564-7 (e- book) 1. Liberalism. 2. Liberty. 3. Slave trade. 4. Commerce. 5. Civilization, Modern. i. Title. jc574.l688 2015 320.51— dc23 2014046258 Cover art: Nelson’s Ship in a Bottle, © Yinka Shonibare mbe. All rights reserved, dAcs/ ars, NY 2014. Photo courtesy Stephen Friedman Gallery, London, and National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, UK. for Juliet This page intentionally left blank CONTENTS CHAPTER 1. THE INTIMACIES OF FOUR CONTINENTS * 1 CHAPTER 2. AUTOBIOGRAPHY OUT OF EMPIRE * 43 CHAPTER 3. A FETISHISM OF COLONIAL COMMODITIES * 73 CHAPTER 4. THE RUSES OF LIBERTY * 101 CHAPTER 5. FREEDOMS YET TO COME * 135 AC KNOW L EDG MENTS * 177 NOTES * 181 REFERENCES * 269 INDEX * 305 1.1 Cutting Sugar Cane in Trinidad, Richard Bridgens (1836). Lithograph from West India Scenery, by Richard Bridgens. © Te British Library Board. CHAPTER 1 THE INTIMACIES OF FOUR CONTINENTS My study investigates the ofen obscured connections between the emer- gence of Eur o pean liberalism, settler colonialism in the Americas, the transatlantic African slave trade, and the East Indies and China trades in the late eigh teenth and early nineteenth centuries. -

William Jardine (Merchant) from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

William Jardine (merchant) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia For other people with the same name see "William Jardine" (disambiguation) William Jardine (24 February 1784 – 27 February 1843) was a Scottish physician and merchant. He co-founded the Hong Kong conglomerate Jardine, Matheson and Company. From 1841 to 1843, he was Member of Parliament for Ashburton as a Whig. Educated in medicine at the University of Edinburgh, Jardine obtained a diploma from the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh in 1802. In the same year, he became a surgeon's mate aboard the Brunswick of the East India Company, bound for India. Captured by the French and shipwrecked in 1805, he was repatriated and returned to the East India Company's service as ship's surgeon. In May 1817, he left medicine for commerce.[1] Jardine was a resident in China from 1820 to 1839. His early success in Engraving by Thomas Goff Lupton Canton as a commercial agent for opium merchants in India led to his admission in 1825 as a partner of Magniac & Co., and by 1826 he was controlling that firm's Canton operations. James Matheson joined him shortly after, and Magniac & Co. was reconstituted as Jardine, Matheson & Co in 1832. After Imperial Commissioner Lin Zexu confiscated 20,000 cases of British-owned opium in 1839, Jardine arrived in London in September, and pressed Foreign Secretary Lord Palmerston for a forceful response.[1] Contents 1 Early life 2 Jardine, Matheson and Co. 3 Departure from China and breakdown of relations 4 War and the Chinese surrender Portrait by George Chinnery, 1820s 5 Death and legacy 6 Notes 7 See also 8 References 9 External links Early life Jardine, one of five children, was born in 1784 on a small farm near Lochmaben, Dumfriesshire, Scotland.[2] His father, Andrew Jardine, died when he was nine, leading the family in some economic difficulty.