The British State at the Margins of Empire Extraterritoriality and Governance in Treaty Port China, 1842-1927

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Case for 1950S China-India History

Before 1962: The Case for 1950s China-India History The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Ghosh, Arunabh. 2017. Before 1962: The Case for 1950s China-India History. The Journal of Asian Studies 76, no. 3: 697-727. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:41288160 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Open Access Policy Articles, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#OAP DRAFT: DO NOT CITE OR CIRCULATE Before 1962: The Case for 1950s China-India History Arunabh Ghosh ABSTRACT China-India history of the 1950s remains mired in concerns related to border demarcations and a teleological focus on the causes, course, and consequence of the war of 1962. The result is an overt emphasis on diplomatic and international history of a rather narrow form. In critiquing this narrowness, this paper offers an alternate chronology accompanied by two substantive case studies. Taken together, they demonstrate that an approach that takes seriously cultural, scientific and economic life leads to different sources and different historical arguments from an approach focused on political (and especially high political) life. Such a shift in emphasis, away from conflict, and onto moments of contact, comparison, cooperation, and competition, can contribute fresh perspectives not just on the histories of China and India, but also on histories of the Global South. Arunabh Ghosh ([email protected]) is Assistant Professor of Modern Chinese History in the Department of History at Harvard University Vikram Seth first learned about the death of “Lita” in the Chinese city of Turfan on a sultry July day in 1981. -

Charles Darwin: a Companion

CHARLES DARWIN: A COMPANION Charles Darwin aged 59. Reproduction of a photograph by Julia Margaret Cameron, original 13 x 10 inches, taken at Dumbola Lodge, Freshwater, Isle of Wight in July 1869. The original print is signed and authenticated by Mrs Cameron and also signed by Darwin. It bears Colnaghi's blind embossed registration. [page 3] CHARLES DARWIN A Companion by R. B. FREEMAN Department of Zoology University College London DAWSON [page 4] First published in 1978 © R. B. Freeman 1978 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the permission of the publisher: Wm Dawson & Sons Ltd, Cannon House Folkestone, Kent, England Archon Books, The Shoe String Press, Inc 995 Sherman Avenue, Hamden, Connecticut 06514 USA British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Freeman, Richard Broke. Charles Darwin. 1. Darwin, Charles – Dictionaries, indexes, etc. 575′. 0092′4 QH31. D2 ISBN 0–7129–0901–X Archon ISBN 0–208–01739–9 LC 78–40928 Filmset in 11/12 pt Bembo Printed and bound in Great Britain by W & J Mackay Limited, Chatham [page 5] CONTENTS List of Illustrations 6 Introduction 7 Acknowledgements 10 Abbreviations 11 Text 17–309 [page 6] LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Charles Darwin aged 59 Frontispiece From a photograph by Julia Margaret Cameron Skeleton Pedigree of Charles Robert Darwin 66 Pedigree to show Charles Robert Darwin's Relationship to his Wife Emma 67 Wedgwood Pedigree of Robert Darwin's Children and Grandchildren 68 Arms and Crest of Robert Waring Darwin 69 Research Notes on Insectivorous Plants 1860 90 Charles Darwin's Full Signature 91 [page 7] INTRODUCTION THIS Companion is about Charles Darwin the man: it is not about evolution by natural selection, nor is it about any other of his theoretical or experimental work. -

Modern Hong Kong

Modern Hong Kong Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Asian History Modern Hong Kong Steve Tsang Subject: China, Hong Kong, Macao, and/or Taiwan Online Publication Date: Feb 2017 DOI: 10.1093/acrefore/9780190277727.013.280 Abstract and Keywords Hong Kong entered its modern era when it became a British overseas territory in 1841. In its early years as a Crown Colony, it suffered from corruption and racial segregation but grew rapidly as a free port that supported trade with China. It took about two decades before Hong Kong established a genuinely independent judiciary and introduced the Cadet Scheme to select and train senior officials, which dramatically improved the quality of governance. Until the Pacific War (1941–1945), the colonial government focused its attention and resources on the small expatriate community and largely left the overwhelming majority of the population, the Chinese community, to manage themselves, through voluntary organizations such as the Tung Wah Group of Hospitals. The 1940s was a watershed decade in Hong Kong’s history. The fall of Hong Kong and other European colonies to the Japanese at the start of the Pacific War shattered the myth of the superiority of white men and the invincibility of the British Empire. When the war ended the British realized that they could not restore the status quo ante. They thus put an end to racial segregation, removed the glass ceiling that prevented a Chinese person from becoming a Cadet or Administrative Officer or rising to become the Senior Member of the Legislative or the Executive Council, and looked into the possibility of introducing municipal self-government. -

That the Earliest Groups of Jews Came to China Via the Overland Silk Road

Jews in China: Legends, History and New Perspectives By PAN Guang Jews in Ancient China: The Case of Kaifeng It was during the Tang Dynasty (around the 7th - 8th Century) that the earliest groups of Jews came to China via the overland Silk Road. Others then may come by sea to the coastal areas before moving inland. A few scholars believe that Jews came to China as early as the Han Dynasty (206 B.C. – 220 A.D.) — some even go so far as to place their arrival earlier, during the Zhou Dynasty (around the 6th Century B.C.) — though there have been no archaeological discoveries that would prove such claims. After entering China, Jews lived in many cities and areas, but it was not until in the Song Dynasty (960-1279) that the Kaifeng Jewish Community formed. In the Northern Song Dynasty, a group of Jews came to the then capital Dongjing (now Kaifeng, as it will be referred to below). They were warmly received by the authorities and allowed to live in Kaifeng as Chinese while keeping their own traditions and religious faith. Thereafter, they enjoyed, without prejudice, the same rights and treatment as the Han peoples in matters of residence, mobility, employment, education, land transactions, religious beliefs and marriage. In such a safe, stable and comfortable environment, Jews soon demonstrated their talents in business and finance, achieving successes in commerce and trade and becoming a rich group in Kaifeng. At the same time, their religious activities increased. In 1163, the Jews in Kaifeng built a synagogue right in the heart of the city. -

Community in Exile: German Jewish Identity Development in Wartime Shanghai, 1938-1945 Alice I

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont CMC Senior Theses CMC Student Scholarship 2011 Community in Exile: German Jewish Identity Development in Wartime Shanghai, 1938-1945 Alice I. Reichman Claremont McKenna College Recommended Citation Reichman, Alice I., "Community in Exile: German Jewish Identity Development in Wartime Shanghai, 1938-1945" (2011). CMC Senior Theses. Paper 96. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses/96 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you by Scholarship@Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in this collection by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CLAREMONT McKENNA COLLEGE COMMUNITY IN EXILE: GERMAN JEWISH IDENTITY DEVELOPMENT IN WARTIME SHANGHAI, 1938-1945 SUBMITTED TO PROFESSOR ARTHUR ROSENBAUM AND DEAN GREGORY HESS BY ALICE REICHMAN FOR SENIOR THESIS ACADEMIC YEAR 2010-2011 APRIL 25, 2011 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ……………………………………………………………………... iii INTRODUCTION …………………………………………………………………………....1 CHAPTER ONE FLIGHT FROM THE NAZIS AND ARRIVAL IN A FOREIGN LAND ……………………………....7 CHAPTER TWO LIFE AND CONDITIONS IN SHANGHAI ………………………………………………….......22 CHAPTER THREE RESPONDING TO LIFE IN SHANGHAI ……………………………………………………….38 CHAPTER FOUR A HETEROGENEOUS COMMUNITY : DIFFERENCES AMONG JEWISH REFUGEES ……………. 49 CHAPTER FIVE MAINTAINING A CENTRAL EUROPEAN IDENTITY : GERMANIC CULTURE COMES TO SHANGHAI ………………………………………………………………………………... 64 CHAPTER SIX YOUTH EXPERIENCE …………………………………………………………………….... 80 CHAPTER SEVEN A COSMOPOLITAN CITY : ENCOUNTERS AND EXCHANGES WITH OTHER CULTURES ……....98 CONCLUSION ………………………………………………………………………….... 108 DIRECTORY OF REFERENCED SURVIVORS ………………………………………………. 112 BIBLIOGRAPHY ………………………………………………………………………….. 117 ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would first like to thank my reader, Professor Arthur Rosenbaum, for all the help that he has given me throughout this process. Without his guidance this thesis would not have been possible. I am grateful for how understanding and supportive he was throughout this stressful year. -

Uncommon Books, Ephemera & Other Works on Paper

Uncommon Books, Ephemera & other works on Paper Asia Bookroom www.AsiaBookroom.com Page 1 Why Include Asian Material in Your Collection? Librarians and collectors are increasingly adding Asian materials to their collections with the aim of providing a more balanced resource that better reflects the world. Including an Asian perspective on a subject within your collection provides an interesting contrast to the more commonly collected Western focused themes and in doing so provides deeper insights into a world that scholars and collectors were frequently previously unaware of. If you might be interested in pursuing this direction Sally Burdon from Asia Bookroom can advise you. Sally has worked with libraries and collectors worldwide and would welcome the opportunity to discuss your collecting interests. Her business Asia Bookroom specialises exclusively in books, ephemera and other materials on paper with an Asian focus. Asia Bookroom Lawry Place We issue many specialised lists by email. Macquarie ACT 2614 Australia Join our mailing list. Ph: +61 2 6251 5191 Fax: +61 2 6251 5536 Email us on [email protected] or Website: www.AsiaBookroom.com visit our website www.AsiaBookroom.com Email: [email protected] Japan & Korea—19th Century Map With Somewhat Quirky English Captions 樺井達之輔 Kabai Tatsunosuke (Editor) 明治改正 大日本精圖 Meiji kaisei dainihon seizu Detailed Map of Great Japan: Revision in Meiji. Folding map measures 70 x 70.5cm a few small closed tears along folds, 3 small holes at folds with only tiny loss. A very nice map in good condition. Nakamura Asakichi 中 村淺吉 Kyoto. 1887. Coloured copperplate map of Japan with Hokkaido and Korea shown in vignettes at the upper left corner and Okinawa (Ryūkyū) and the Ogasawara Islands in vignettes in the upper middle section of the map in the middle and to the right are the Eastern and Western hemispheres. -

Imperial China and the West Part I, 1815–1881

China and the Modern World: Imperial China and the West Part I, 1815–1881 The East India Company’s steamship Nemesis and other British ships engaging Chinese junks in the Second Battle of Chuenpi, 7 January 1841, during the first opium war. (British Library) ABOUT THE ARCHIVE China and the Modern World: Imperial China and the West Part I, 1815–1881 is digitised from the FO 17 series of British Foreign Office Files—Foreign Office: Political and Other Departments: General Correspondence before 1906, China— held at the National Archives, UK, providing a vast and significant primary source for researching every aspect of Chinese-British relations during the nineteenth century, ranging from diplomacy to trade, economics, politics, warfare, emigration, translation and law. This first part includes all content from FO 17 volumes 1–872. Source Library Number of Images The National Archives, UK Approximately 532,000 CONTENT From Lord Amherst’s mission at the start of the nineteenth century, through the trading monopoly of the Canton System, and the Opium Wars of 1839–1842 and 1856–1860, Britain and other foreign powers gradually gained commercial, legal, and territorial rights in China. Imperial China and the West provides correspondence from the Factories of Canton (modern Guangzhou) and from the missionaries and diplomats who entered China in the early nineteenth century, as well as from the envoys and missions sent to China from Britain and the later legation and consulates. The documents comprising this collection include communications to and from the British legation, first at Hong Kong and later at Peking, and British consuls at Shanghai, Amoy (Xiamen), Swatow (Shantou), Hankow (Hankou), Newchwang (Yingkou), Chefoo (Yantai), Formosa (Taiwan), and more. -

RECORDS CODIFICATION MANUAL Prepared by the Office Of

RECORDS CODIFICATION MANUAL Prepared by The Office of Communications and Records Department of State (Adopted January 1, 1950—Revised January 1, 1955) I I CLASSES OF RECORDS Glass 0 Miscellaneous. I Class 1 Administration of the United States Government. Class 2 Protection of Interests (Persons and Property). I Class 3 International Conferences, Congresses, Meetings and Organizations. United Nations. Organization of American States. Multilateral Treaties. I Class 4 International Trade and Commerce. Trade Relations, Treaties, Agreements. Customs Administration. Class 5 International Informational and Educational Relations. Cultural I Affairs and Programs. Class 6 International Political Relations. Other International Relations. I Class 7 Internal Political and National Defense Affairs. Class 8 Internal Economic, Industrial and Social Affairs. 1 Class 9 Other Internal Affairs. Communications, Transportation, Science. - 0 - I Note: - Classes 0 thru 2 - Miscellaneous; Administrative. Classes 3 thru 6 - International relations; relations of one country with another, or of a group of countries with I other countries. Classes 7 thru 9 - Internal affairs; domestic problems, conditions, etc., and only rarely concerns more than one I country or area. ' \ \T^^E^ CLASS 0 MISCELLANEOUS 000 GENERAL. Unclassifiable correspondence. Crsnk letters. Begging letters. Popular comment. Public opinion polls. Matters not pertaining to business of the Department. Requests for interviews with officials of the Department. (Classify subjectively when possible). Requests for names and/or addresses of Foreign Service Officers and personnel. Requests for copies of treaties and other publications. (This number should never be used for communications from important persons, organizations, etc.). 006 Precedent Index. 010 Matters transmitted through facilities of the Department, .1 Telegrams, letters, documents. -

VOL. XXIX No. 3 March 2017 Rs. 20.00 2

1 VOL. XXIX No. 3 March 2017 Rs. 20.00 2 Ambassador Luo Zhaohui and his wife Dr. Jiang Yili met Ambassador Luo Zhaohui and his wife Dr. Jiang Yili met with His Excellency Ram Nath Kovind, Governor of Bihar. with the Honourable Mamata Benerjee, Chief Minister of West Bengal. Ambassador Luo Zhaohui and his wife Dr. Jiang Yili met Ambassador Luo Zhaohui met with Mr. Suresh Prabhu, with Ms. Nirupama Rao and her husband, former Foreign Railway Minister of India. Secretary and Ambassador to China of India. Ambassador Luo Zhaohui met with Mr. Sitaram Yechury, The Chinese Embassy and Chinese enterprises had a General Secretary of the Communist Party of India friendly basketball match. (Marxist). NPC & CPPCC Annual Sessions 2017 1. NPC & CPPCC Annual Sessions 2017 4 2. Transcript of Premier Li Keqiang’s Meeting with the Press at the Fifth Session 6 of the 12th National People's Congress S 3. Foreign Minister Wang Yi Meets the Press 16 4. Chinese Leaders Review Government Work Report with Lawmakers 26 5. China's National Legislature Concludes Annual Session 27 6. China's National Legislature Stresses Unity Around Xi as Core 29 External Affairs T 1. China, Saudi Arabia Agree to Boost All-Round Strategic Partnership 31 2. President Xi Meets U.S. Secretary of State 33 2. Xi Jinping Meets with King Norodom Sihamoni and Queen Mother Norodom 34 Monineath Sihanouk of Cambodia 3. Li Keqiang and UK Prime Minister Theresa May Exchange Congratulatory 36 Messages on the 45th Anniversary of the Establishment of Ambassadorial Level Diplomatic Relations Between China and the UK 4. -

Sino-British Agreement and Nationality: Hong Kong's Future in the Hands of the People's Republic of China

UCLA UCLA Pacific Basin Law Journal Title The Sino-British Agreement and Nationality: Hong Kong's Future in the Hands of the People's Republic of China Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9j3546s0 Journal UCLA Pacific Basin Law Journal, 8(1) Author Chua, Christine Publication Date 1990 DOI 10.5070/P881021965 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California THE SINO-BRITISH AGREEMENT AND NATIONALITY: HONG KONG'S FUTURE IN THE HANDS OF THE PEOPLE'S REPUBLIC OF CHINA Christine Chua* I. INTRODUCTION On July 1, 1997, the United Kingdom will officially relinquish its sovereignty over Hong Kong' to the People's Republic of China (PRC). The terms for the transfer of governmental control are set forth in the Joint Declaration of the Government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and the Govern- ment of the People's Republic of China on the Question of Hong Kong (hereinafter, "Joint Declaration"), which was signed by rep- resentatives for both governments on December 19, 1984. The terms likewise appear in the Memoranda exchanged by the United 2 Kingdom and PRC governments on the signing date. Set forth in the Joint Declaration is the PRC's intent to estab- lish the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (SAR). 3 Rules for implementing the separate government of the Hong Kong SAR are also enumerated. 4 The creation of the Hong Kong SAR is au- thorized by a provision in the PRC Constitution' originally in- * J.D., 1989, UCLA School of Law; B.A., 1985, Cornell University. -

Part 7: Invasions, Rebellions, and the End of Imperial China Part 7 Introduction Pre-Modern Vs

Part 7: Invasions, Rebellions, and the End of Imperial China Part 7 Introduction Pre-modern vs. Modern When does modern Chinese history begin? Some say during the Opium War, the late 1830s and 1840s. Others date modern history from 1919 and the May Fourth Movement. In this course we take the 18th century, when the Qing was at its height, to begin modern Chinese history. Considering that modern history bears some relation to the present, what events signified the beginning of that period? In Europe, historians often chose 1789, the French Revolution. The signifying events, the transitional events, for China begin with its transition from empire to nation-state, with population growth, with the inclusion of Xinjiang and Tibet during the Qianlong reign, and with the challenges of maintaining unity in a multi-ethnic population. Encounter with the West In the 19th century this evolving state ran head-on into the mobile, militarized nation of Great Britain, the likes of which it has never seen before. This encounter was nothing like the visits from Jesuit missionaries (footnote 129 on page 208) or Lord Macartney (page 253). It challenged all the principles of imperial rule. Foreign Enterprise Today’s Chinese economy has its roots in the Sino-foreign enterprises born during these early encounters. Opium was one of its main enterprises. Christianity was a kind of enterprise. These enterprises combined to weaken and humiliate the Qing. As would be said of a later time, these foreign insults were a “disease of the skin.”165 It was the Taiping Rebellion that struck at the heart. -

841D211f0b4bb19c93c26e63b9

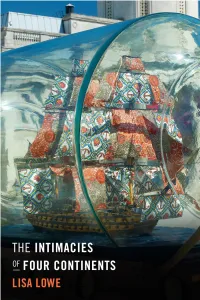

THE INTIMACIES OF FOUR CONTINENTS This page intentionally left blank THE INTIMACIES OF FOUR CONTINENTS LISA LOWE Duke University Press Durham and London 2015 © 2015 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid-f ree paper ∞ Typeset in Minion Pro by Westchester Publishing Services Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Lowe, Lisa. Te intimacies of four continents / Lisa Lowe. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 978-0-8223-5863-3 (hardcover : alk. paper) isbn 978-0-8223-5875-6 (pbk. : alk. paper) isbn 978-0-8223-7564-7 (e- book) 1. Liberalism. 2. Liberty. 3. Slave trade. 4. Commerce. 5. Civilization, Modern. i. Title. jc574.l688 2015 320.51— dc23 2014046258 Cover art: Nelson’s Ship in a Bottle, © Yinka Shonibare mbe. All rights reserved, dAcs/ ars, NY 2014. Photo courtesy Stephen Friedman Gallery, London, and National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, UK. for Juliet This page intentionally left blank CONTENTS CHAPTER 1. THE INTIMACIES OF FOUR CONTINENTS * 1 CHAPTER 2. AUTOBIOGRAPHY OUT OF EMPIRE * 43 CHAPTER 3. A FETISHISM OF COLONIAL COMMODITIES * 73 CHAPTER 4. THE RUSES OF LIBERTY * 101 CHAPTER 5. FREEDOMS YET TO COME * 135 AC KNOW L EDG MENTS * 177 NOTES * 181 REFERENCES * 269 INDEX * 305 1.1 Cutting Sugar Cane in Trinidad, Richard Bridgens (1836). Lithograph from West India Scenery, by Richard Bridgens. © Te British Library Board. CHAPTER 1 THE INTIMACIES OF FOUR CONTINENTS My study investigates the ofen obscured connections between the emer- gence of Eur o pean liberalism, settler colonialism in the Americas, the transatlantic African slave trade, and the East Indies and China trades in the late eigh teenth and early nineteenth centuries.