Economic Effects of Covid-19 in Luxembourg First Recovid Working Note with Preliminary Estimates

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unclassified Xxix S E C\E T

A. Fighter; Total claims against enemy aircraft during the month were 39-0-13 in the air and 1-0-2 on the ground. Missions 25 Sorties 296 d. Flak.— XIX TAC aircraft losses for the month because of flak Tons Bombs on Tgts 128 were unusually high. Out of the 50 aircraft lost, 35 were victims of Tons Frags 14.69 flak. The enemy, realizing that the greatest threat to the success of Tons Napalm 7.15 its ARD3NNBS salient was American air power, built up a very strong Tons Incendiaries 10.25 anti-aircraft defense around the entire area. Rockets 22 Claims (air) 4-1-1 The TTY TAC A-2 Flak Officer, reporting near the end of the Geraan retreat from the Bulge area, said: B. Reconnaissance: "The proportion of flak protection to troops and area involved (in Tac/R Sorties 58/36 1. INTRODUCTION. the ARDENNES area) was higher than in any previous operation in this P/R Sorties 7/6 war's history. Artillery sorties 4/2 a. General.— opening the year of 1945, the XIX Tactical Air Com mand-Third US Army team had a big job on its hands before it could re "Flak units were apparently given the highest priorities in supply C. Night Fighter: sume the assault of the SIEGFRIED LINE. The German breakthrough into of fuel and ammunition. They must also have been given a great degree of the ARDENNES had been checked but not yet smashed. The enemy columns freedom in moving over roads always taxed to capacity. Sorties 15 which had surged toward the MEUSE were beginning to withdraw, for the Claims (air) 1-0-0 v wily Rundstedt's best-laid plans had been wrecked on the rock of BAS "In addition to the tremendous quantities of mobile flak assigned TOGNS. -

Proof of Reproduction of Salmon Returned to the Rhine System

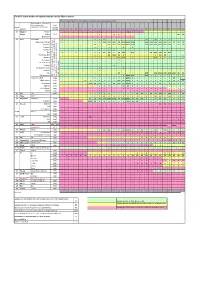

Proof of reproduction of salmon returned to the Rhine system Year of spawning proof (reproduction during the preceding autumn/winter) Project water - Selection of the most important First Countr tributaries (* no stocking) salmon y System stocking 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 D Wupper- Wupper / / / / / / / / 0 / / / / / (X) / / / / / / / / / / X Dhünn Dhünn 1993 / / / / / / / / 0 / / X X / / / / / / / / / / / XX XX Eifgenbach / / / / / / / / / / / / 0 / / / / / / / / / / / / / D Sieg Sieg NRW X / / / / / / X 0 XX / / / / / / / / XX / XX 0 0 0 / / / Agger (lower 30 km) X / / / / / / 0 0 XXX XXX XXX XX XXXX XXXX XXXX / / XXX XXX XXX XXX XXX XX XX XX XX Naafbach / / / / / / / XX 0 / XXX XXX XXX XXXX XXXX XXXX / / XXX XXX XXX XXXX XXX XXX 0 XX XX Pleisbach / / / / / / / 0 / / 0 / / X / X / / / / / / / / / / Hanfbach / / / / / / / / 0 / 0 X / / / / / / / / / / / / / / Bröl X / / X / / / 0 0 XX XX 0 XX XXX / XXX / / / XX XXX XXX XX XXX / / Homburger Bröl / / / / / / / 0 0 / XX XXX XX X / / / / / / 0 XX XX 0 / / 0 Waldbröl / / / / / / / 0 0 / 0 0 XXX XXX / 0 / / / / XXX 0 0 0 / / 0 Derenbach / / / / / / / / / / / / 0 / / / / / / / / / / / / / Steinchesbach / / / / / / / / / / / / 0 / / / / / / / / / / / / / Krabach / / / / / / / / / / / X / / / / / / / / / / / / / / Gierzhagener Bach / / / / / / / / 0 / / / / X / / / / / / / / / / / / Irsenbach / / / / / / / / 0 / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / Sülz / / / / / / / 0 0 / / / XX / / / / / -

Die Natur in Der Luxemburger Moselregion Découvrir La Nature Dans La Région De La Experience the Natural Environment in the Erleben

Die Natur in der Luxemburger Moselregion Découvrir la nature dans la région de la Experience the natural environment in the erleben. Kanuausflüge auf Mosel und Sauer. Moselle luxembourgeoise. Excursions en Luxemburgish Moselle region. Canoe trips canoë sur la Moselle et la Sûre. on the Moselle and the Sauer. Das Kanuwandern als aktive Freizeitbeschäftigung steht jedem offen, La randonnée en canoë en tant qu’activité de loisirs est un sport Canoeing is an activity that can be enjoyed by everyone, be it in the ob auf der Mosel als gemächlicher Wanderfluss oder auf der Sauer mit ouvert à tous: que ce soit sur la Moselle, pour une excursion paisible, form of a leisurely excursion along the Mosel or a trip down the Sauer leichten Stromschnellen, ob jung oder alt, jeder kommt im Miseler- ou sur la Sûre avec ses légers rapides. Jeunes ou moins jeunes: dans la with its gentle rapids. Miselerland has something to offer for every- land auf seine Kosten! région du Miselerland, vous trouverez de quoi vous réjouir ! one whatever their age! DIE ANLEGESTELLEN LES POINTS D’ACCOSTAGE THE LANDING PLACES Dank den Anlegern entlang der Mosel und der Sauer, entscheiden Sie Grâce aux points d’accostage le long de la Moselle et de la Sûre, c’est Thanks to the landing places along the Mosel and the Sauer you can selbst an welchem Winzerort Sie einen Stopp einlegen. vous qui décidez dans quel village viticole vous allez faire une halte. choose in which viticulture village you like to stop. Entdecken Sie mit der ganzen Familie naturbelassene Seitentäler zu Découvrez à pied avec toute la famille les vallées adjacentes, qui You can discover the natural preserved lateral valleys by foot with Fuß, besichtigen Sie interessante Museen oder genießen Sie einfach ont conservé leur état naturel. -

Der Gänsesäger Mergus Merganser Als Brutvogel in Luxemburg

Der Gänsesäger Mergus merganser als Brutvogel in Luxemburg Patric Lorgé, Peter Brixius, Karl-Heinz Heyne und Norbert Roth E-mail: [email protected] Zusammenfassung: Vier Bruten des Gänsesägers Mergus merganser an den Flüssen Sauer und Syr werden ausführlich beschrieben. Es handelt sich hierbei um die ersten Brutnachweise für Luxemburg, die fernab der traditionellen Brutgebiete der Art statt- fanden. Sie werden in Bezug zu den geografisch nächstgelegenen Brutvorkommen des Gänsesägers kurz diskutiert. Abstract: The Common Merganser Mergus merganser as a breeding bird in Luxembourg Four broods of the Common Merganser Mergus merganser on the rivers Sauer and Syre are described in detail. They constitute the first breeding records for Luxembourg and occurred far from traditional breeding grounds of the species. They are discussed in rela- tion to the geographically nearest breeding records for the Common Merganser. Résumé: Le Harle bièvre Mergus merganser comme nicheur au Luxembourg Quatre nichées du Harle bièvre Mergus merganser le long des rivières Sûre et Syre sont décrites en détail. Elles constituent les premiers cas de reproduction pour le Grand-Duché de Luxembourg, bien loin des zones de reproduction habituelles de l’espèce. Der Gänsesäger (Mergus merganser; lëtz. Grousse Seeër) galt bisher in Luxemburg als typi- scher Wintergast, der vor allem nicht zu tiefe, aber schnell fließende Gewässer der Forellen- region aufsucht. Von Ende Oktober bis Mitte März beträgt sein Winterbestand etwa 120 bis 160 Individuen (Winter Water Bird Count), die sich auf die Flüsse Sauer und Our, den Stausee Esch/ Sauer sowie in geringerem Maße auf die Seen bei Echternach und Weiswampach und die Mosel verteilen. -

IIYICL WORLD Whar II

IIYICL WORLD WhAR II A CHRONOLOGY OCTOBER 1944 'k, t 77 11 r. .11 ThAR DEPRTR;EN4T SPECIAL STAFF -1 - - - ":"! ' 1M il. 1 7 I i.: rl"-1' 11 0- I'-J,"I;I i, 1. f :A-_' , :.,f-,i , , ,- , 1." 4. TABLE OF CONTENTS Section I. North and Latin American Theaters ... .. 1 II. Western European Theater Part 1: Twenty-first Army-Group. .... 3 Part 2; Twelfth Army Group .. .. .. 39 Part 3' Sixth Army Group 81 Part 4: Strategic Air . ....... 107 III. Eastern European Theater .......... 117 IV. Mediterranean Theater .......... 145 V. Asiatic Theater ..... ..... .... 245 VI. Pacific Ocean Areas ......... .. 281 VII. Southwest Pacific Theater . 295 VIII. Political, Economic, Psychological ..... 357 - a- - 1 ft '.ftft ft 9 ft -.5 t, 1.k »<&? «- ft.,.-, ft I' I A S f S«,' i -ft 'Il 1 * Aft a ! E Oct SectionNLATIN THEAERS NORTH A A Oct Section I: NORTH AND LATIN NHERICAN THEATHRS 1944 4 Brazil: Minister of Marine, Adm. Guilhelm, states that the Brazilian Navy will soon be responsible for the patrolling of the entire South Atlantic area. 10 Greenland: Landing party from USS Eastwind raids German weather station on island off NE coast of Greenland, taking 12 prisoners and much scientific equipment. I . x, ¾ f ". -. 1 3 s,!N e- I^IM 7^ rM Oct Section iI:; ESTERN EUROPEAIh HETSER 1944 Part I: Twenty-first'A rrAy Group 1 BRITISH SECOND ARMZ VIII Corps On E flank, patrols are active along Deurne- Meijel road. XXX Corps Forty-third Div repulses tank suppoirted attacks from vicinity ofHuissen, NE of Nijrmegen, and engages hostile groups S of the Neder Rijn WVof Arnhem. -

AP Human Geography Summer Assignment.Pdf

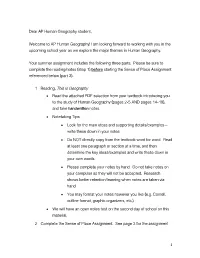

Dear AP Human Geography student, Welcome to AP Human Geography! I am looking forward to working with you in the upcoming school year as we explore the major themes in Human Geography. Your summer assignment includes the following three parts. Please be sure to complete the reading/notes (step 1) before starting the Sense of Place Assignment referenced below (part 2). 1 Reading, This is Geography • Read the attached PDF selection from your textbook introducing you to the study of Human Geography (pages 2-5 AND pages 14-19), and take handwritten notes. • Notetaking Tips: • Look for the main ideas and supporting details/examples— write these down in your notes • Do NOT directly copy from the textbook word for word. Read at least one paragraph or section at a time, and then determine the key ideas/examples and write these down in your own words. • Please complete your notes by hand. Do not take notes on your computer as they will not be accepted. Research shows better retention/learning when notes are taken via hand. • You may format your notes however you like (e.g. Cornell, outline format, graphic organizers, etc.) • We will have an open notes test on the second day of school on this material. 2 Complete the Sense of Place Assignment. See page 3 for the assignment 1 3 Map Work: • Memorize the 50 states of the United States. Go to https://lizardpoint.com/geography/usa-quiz.php to use an online quiz program to test yourself. • Memorize the AP Human Geography World Regions maps—both “a big picture view” and “a closer look.” See page 4. -

To Discover and Enjoy the Mosel Region

Discover and enjoy the Moselle countryside 2 At the top A warm welcome to the Moselle, Saar und Ruwer ... a countryside of superlatives awaiting your visit! It is here that winegrowers produce top international wines, it is here that the Romans founded the oldest city of Germany, it is here that you will find one of the most successful combinations of rich, ancient culture and countryside, which is sometimes gentle and sometimes spectacular. As far as the art of living is concerned, the proximity to France and Luxem- bourg inspires not only the cuisine of the Moselle region. There is hardly any other holiday region that has so many fascinating facets. 3 Winegrowers who cultivate steep hillsi INSIDE GERMANY the Moselle care and manual work. A winegro- has cut its way through deep wer must not suffer from vertigo gorges and countless meanders here! The steep slopes and terraces, into the mountains over a distance with their mild micro-climate and of more than 240 kilometres, until slate ground that stores the heat, it meets Father Rhine in Koblenz. are the ideal conditions for the Europe’s steepest vineyard, the Riesling grape, which produces the Bremmer Calmont, with a 68° uniquely delicate fruity and tangy slope, is situated in the largest wines along the Moselle, Saar and enclosed area of cliffs in the world: Ruwer. The dry Moselle wines, in roughly half of the Moselle vine- particular, that are cultivated by the yards, comprising around 10,000 5000 or so winegrowers, with a hectares in total, are cultivated in wealth of individual nuances, are 4 this way, which demands a lot of an excellent accompaniment to ides are heroes delicate dishes. -

Raderlebniskarte Eifel-Mosel-Hunsrück

RegioRadler MaareMosel (RegioLinie 300) RegioRadler Vulkaneifel (RegioLinie 500) RegioRadler Untermosel (Linie 630) RegioRadler Hunsrück (Linie 250) 1 Bernkastel-Kues – Daun 2 Gerolstein – Cochem 3 Treis-Karden – Emmelshausen 4 Emmelshausen – Bingen vom 1. April bis 1. November 2014 vom 1. April bis 1. November 2014 vom 1. Mai bis 1. November 2014 vom 1. Mai bis 1. November 2014 RMV Rhein-Mosel Verkehrsgesellschaft mbH RMV Rhein-Mosel Verkehrsgesellschaft mbH Infos: Tel. 01805 / 00 11 83 * Infos: Tel. 01805 / 00 11 83 * Infos: rhb rheinhunsrückbus GmbH Infos: rhb rheinhunsrückbus GmbH www.bahn.de/rheinmoselbus www.bahn.de/rheinmoselbus Tel. 06761 / 90 66-0 | www.rhb-bus.de Tel. 06761 / 90 66 -0 | www.rhb-bus.de Montag bis Freitag täglich täglich Samstag, Sonn- und Feiertag A A 1 1 2 ✆ Emmelshausen, Bahnhof 12.05 16.05 Bernkastel-Kues, Forum 6.22 8.04 10.04 10.04 12.04 | 18.04 18.04 20.04 Gerolstein, Bahnhof 6.15 6.55 7.15 9.15 11.15 13.15 15.15 Treis-Karden, Bahnhof 9.50 16.50 – Zentrum am Park 12.06 16.06 Zeltingen, Kreissparkasse | 8.14 10.14 | 12.14 alle 18.14 | 20.14 Daun, ZOB 6.39 7.19 7.39 9.39 11.39 13.39 15.39 – Marktplatz 10.00 17.00 Kastellaun, Markt 8.23 12.23 16.23 Wittlich, Hbf. an 6.50 8.27 10.27 10.33 12.27 2 18.27 18.33 20.27 Daun, ZOB 6.42 7.22 7.42 9.42 11.42 13.42 15.42 Lützbach, Staustufe 10.05 17.05 – Busbahnhof (Südstraße) 8.26 12.26 16.26 VRT Wittlich, Hbf. -

A Companion to Environmental Geography Blackwell Companions to Geography

A Companion to Environmental Geography Blackwell Companions to Geography Blackwell Companions to Geography is a blue-chip, comprehensive series covering each major subdiscipline of human geography in detail. Edited and contributed by the disciplines’ leading authorities each book provides the most up to date and authoritative syntheses available in its fi eld. The overviews provided in each Com- panion will be an indispensable introduction to the fi eld for students of all levels, while the cutting-edge, critical direction will engage students, teachers and practi- tioners alike. Published 1. A Companion to the City Edited by Gary Bridge and Sophie Watson 2. A Companion to Economic Geography Edited by Eric Sheppard and Trevor J. Barnes 3. A Companion to Political Geography Edited by John Agnew, Katharyne Mitchell and Gerard Toal (Gearóid Ó Tuathail) 4. A Companion to Cultural Geography Edited by James S. Duncan, Nuala C. Johnson and Richard H. Schein 5. A Companion to Tourism Edited by Alan A. Lew, C. Michael Hall and Allan M. Williams 6. A Companion to Feminist Geography Edited by Lise Nelson and Joni Seager 7. A Companion to Environmental Geography Edited by Noel Castree, David Demeritt, Diana Liverman and Bruce Rhoads 8. Handbook to GIS Edited by John Wilson and Stewart Fotheringham A Companion to Environmental Geography Edited by Noel Castree, David Demeritt, Diana Liverman & Bruce Rhoads A John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., Publication This edition fi rst published 2009 © 2009 Blackwell Publishing Ltd Blackwell Publishing was acquired by John Wiley & Sons in February 2007. Blackwell’s publishing program has been merged with Wiley’s global Scientifi c, Technical, and Medical business to form Wiley-Blackwell. -

A Preliminary Telemetry Study of the Migration of Silver European Eel (Anguilla Anguilla L.) in the River Mosel, Germany

EFF 015 Ecology of Freshwater Fish 2003: 12: 1–7 Copyright # Blackwell Munksgaard2003 Printedin Denmark Á All rights reserved A preliminary telemetry study of the migration of silver European eel (Anguilla anguilla L.) in the River Mosel, Germany Behrmann-Godel J, Eckmann R. A preliminary telemetry study of the J. Behrmann-Godel, R. Eckmann migration of silver European eel (Anguilla anguilla L.) in the River Limnological Institute, University of Konstanz, Mosel, Germany. 78457 Konstanz, Germany Ecology of Freshwater Fish 2003: 12: 000–000. # Blackwell Munksgaard, 2003 Abstract – To study the behaviour of silver eels (Anguilla anguilla L.) during their downstream migration, particularly near a hydroelectric power dam, we tagged nine eels with ultrasonic transmitters and tracked their paths in the River Mosel, Germany. The onset of migration coincided with the first flood event that followed the full moon but was independent of daytime, because migration and turbine passage occurred during both day and night. During migration eels swam actively downstream with a velocity of 0.3–1.2 m Á sÀ1. When migrating eels arrived at the dam, they either passed through the turbines immediately or stayed upstream of the powerhouse for up to 8 days, showing a characteristic circling Key words: [Q1] behaviour. Circling eels repeatedly approached the trashrack, J.Behrmann-Godel,Limnological Institute,University sprinted upstream, and finally passed through the turbines with of Konstanz, 78457 Konstanz, Germany; the next high water discharge. These observations are discussed Tel.: þ49 7531882828; fax: þ49 7531883533; with regard to the design of appropriate downstream passage e-mail: [email protected] facilities. -

5 1 2 1 4 6 8 3 3 5 7 9 10 7 8 9 10 11 12 11

Noch Fragen rund um C D E F G H I J Ihren Ausflug? Sie möchten wissen, ob es Einkehrmöglichkeiten auf der Strecke gibt oder welche Highlights Sie auf der Tour 1 1 erwarten? Diese Ansprechpartner helfen Ihnen gerne weiter: Ahrtal-Tourismus Bad Neuenahr-Ahrweiler e. V. Tel. 02641 / 91710 www.ahrtal.de Was kostet eine Fahrt? Eifel Tourismus GmbH Tel. 06551 / 96 56 0 Für Fahrten innerhalb der Verkehrsverbünde bieten sich im www.eifel.info 2 2 VRM die günstige Tageskarte oder Minigruppenkarte bzw. im VRT das TagesTicket Single oder TagesTicket Gruppe an. Bei Fahrten über die Verbundgrenze hinaus Bequem unterwegs mit den Hunsrück-Touristik GmbH Linie 844 gelten andere Tarife. Beispielsweise kommt bei Fahrten RadBus Ahr-Voreifel Tel. 06543 / 50 77 00 mit dem RadBus AhrVoreifel aus Rheinbach (NRW) in den RadBussen www.hunsruecktouristik.de Kreis Ahrweiler der VRSTarif zur Anwendung. Da die schönsten Radrouten nicht gleich vor der Haustür Jetzt unter ▶ In allen RadBussen kostet eine Fahrrad karte 3 Euro beginnen, bringen Sie jetzt insgesamt 21 RadBusse auf radbusse.de Mosellandtouristik GmbH je Fahrt für das Fahrrad eines Er wachsenen und 2 Euro teilweise neuen Streckenabschnitten zu den besten Tel. 06531 / 97 330 je Fahrt für das Fahrrad eines Kindes bis einschließlich Einstiegspunkten für Ihre Tour. Sparen Sie sich Ihre Energie buchen! www.visitmosel.de 14 Jahre. Im VulkanExpreß ist die Fahrrad mitnahme für die wirklich schönen Ausblicke entlang der Radstrecke kostenlos. und lassen Sie die RadBusse die teilweise beschwerliche Vulkan- Anfahrt übernehmen. Da sind zum Beispiel die Anstiege ▶ Die Plätze für Fahrräder in den RadBussen können RadBusse Naheland-Touristik GmbH 3 3 in der Eifel oder im Hunsrück, die ungeübten Radfahrern Expreß schnell vergeben sein. -

Rund Um Trier

BewegensWert! Rund um Trier Rad- & WanderTouren Routen-Tipps mit Karten www.trier-info.de Radfahren und Wandern in der Urlaubsregion Trier Urlaubsregion Trier – Paradies für Radler & Wanderer Die Urlaubsregion Trier hat sich in den letzten Jahren zu einem wahren Paradies für Radler und Wanderer entwickelt. Eingebettet in ein reizvolles Umland, mit den Bergen und Wäldern von Eifel und Hunsrück sowie den einzigartigen Flusstälern von Mosel, Saar, Ruwer, Kyll und Sauer, übt diese faszinierende Natur- und Kultur- landschaft eine unwiderstehliche Anziehungskraft auf Radler und Wanderer aus. Premium-Radwege wie der Mosel-Radweg, Ruwer-Hochwald-Radweg oder der Saar-Radweg laden zu genuss- vollen Touren per Rad ein – die Berge von Eifel und Hunsrück zu anspruchsvollen Mountainbike- und Rennradtouren. Auf ausgezeichneten Premiumwanderwegen der Extraklasse entdecken Wanderer die einmalige Wanderkulisse der Urlaubsregion Trier. Die vorliegende Broschüre „BewegensWert!“ gibt Ihnen einen Überblick über die Rad- und Wanderwege in der Region rund um Trier. Darüber hinaus finden Sie Tourenvorschläge, nützliche Tipps und vieles mehr in dieser Broschüre. Sie werden schnell feststellen: Die Urlaubsregion Trier ist „BewegensWert!“ – egal ob mit dem Rad oder zu Fuß. www.trier-info.de 1 BewegensWert! Radfahren und Wandern in der Urlaubsregion Trier Inhalt Radfahren Premium-Radrouten 4 Weitere Radwege 14 Tourenvorschläge 16 Mountainbike 24 Rennrad 26 Wissenswertes von A – Z 27 Wandern Premiumwanderwege 32 Weitere Wanderwege 39 Tourenvorschläge 42 Wissenswertes von A – Z 52 Touristische Informationsstellen 54 Übersichtskarte Umschlagklappe 2 3 Radfahren | Premium-Radrouten | Anzeige Radfahren | Premium-Radrouten | Anzeige Premium- Radrouten 4 5 Radfahren | Premium-Radrouten Anzeigen Mosel-Radweg: Perl Trier Koblenz HOTEL k k HAUS AM BERG • familiär geführtes Hotel mit viel Liebe zum Detail komplett renoviert • ruhig am Waldrand, 6 km zur City • kostenlose Tiefgarage, Stadtbus 50 m • 3–4 Pers.