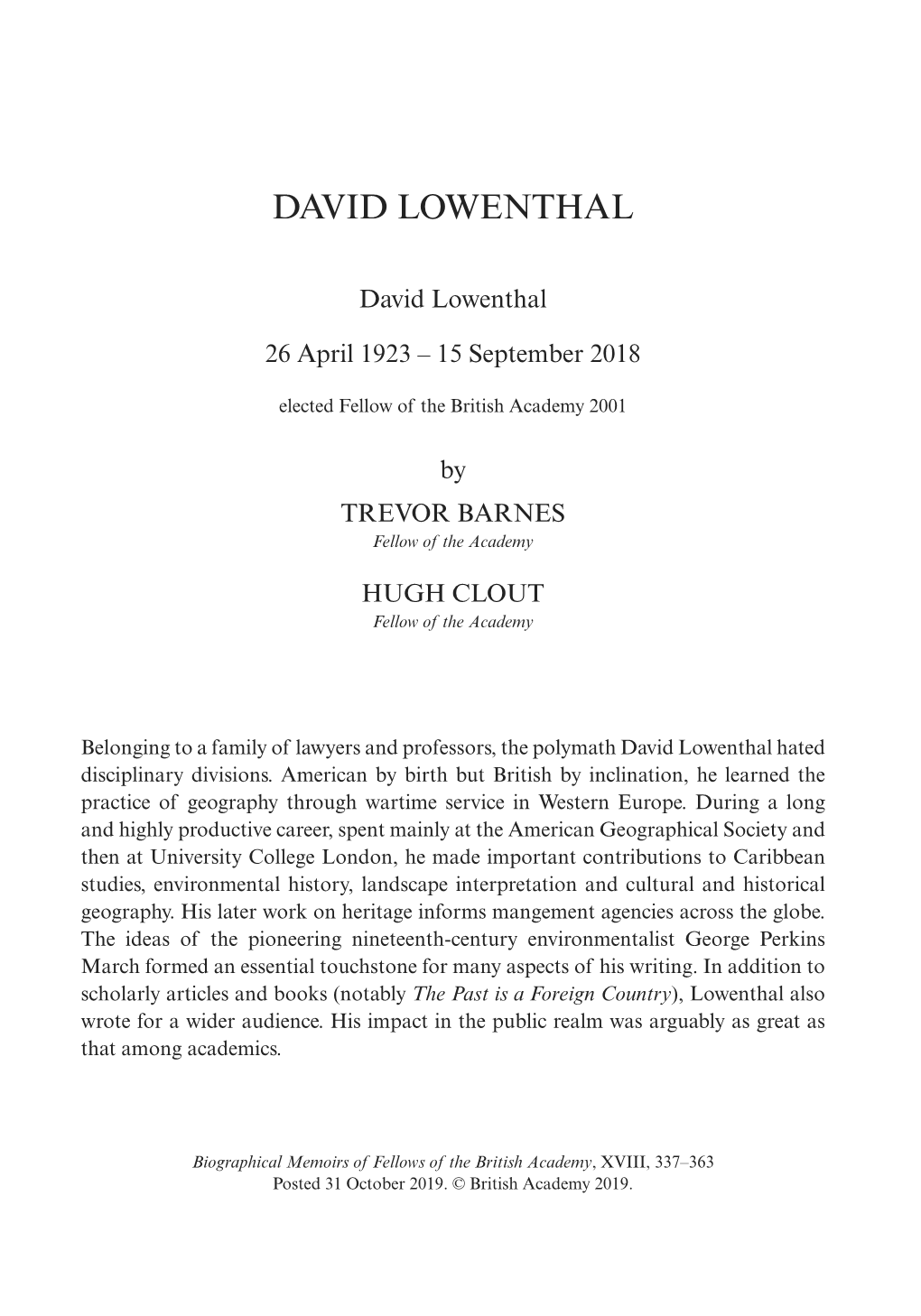

David Lowenthal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Department of Justice and the Limits of the New Deal State, 1933-1945

THE DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE AND THE LIMITS OF THE NEW DEAL STATE, 1933-1945 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY AND THE COMMITTEE ON GRADUATE STUDIES OF STANFORD UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Maria Ponomarenko December 2010 © 2011 by Maria Ponomarenko. All Rights Reserved. Re-distributed by Stanford University under license with the author. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- Noncommercial 3.0 United States License. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/us/ This dissertation is online at: http://purl.stanford.edu/ms252by4094 ii I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. David Kennedy, Primary Adviser I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Richard White, Co-Adviser I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Mariano-Florentino Cuellar Approved for the Stanford University Committee on Graduate Studies. Patricia J. Gumport, Vice Provost Graduate Education This signature page was generated electronically upon submission of this dissertation in electronic format. An original signed hard copy of the signature page is on file in University Archives. iii Acknowledgements My principal thanks go to my adviser, David M. -

Unclassified Xxix S E C\E T

A. Fighter; Total claims against enemy aircraft during the month were 39-0-13 in the air and 1-0-2 on the ground. Missions 25 Sorties 296 d. Flak.— XIX TAC aircraft losses for the month because of flak Tons Bombs on Tgts 128 were unusually high. Out of the 50 aircraft lost, 35 were victims of Tons Frags 14.69 flak. The enemy, realizing that the greatest threat to the success of Tons Napalm 7.15 its ARD3NNBS salient was American air power, built up a very strong Tons Incendiaries 10.25 anti-aircraft defense around the entire area. Rockets 22 Claims (air) 4-1-1 The TTY TAC A-2 Flak Officer, reporting near the end of the Geraan retreat from the Bulge area, said: B. Reconnaissance: "The proportion of flak protection to troops and area involved (in Tac/R Sorties 58/36 1. INTRODUCTION. the ARDENNES area) was higher than in any previous operation in this P/R Sorties 7/6 war's history. Artillery sorties 4/2 a. General.— opening the year of 1945, the XIX Tactical Air Com mand-Third US Army team had a big job on its hands before it could re "Flak units were apparently given the highest priorities in supply C. Night Fighter: sume the assault of the SIEGFRIED LINE. The German breakthrough into of fuel and ammunition. They must also have been given a great degree of the ARDENNES had been checked but not yet smashed. The enemy columns freedom in moving over roads always taxed to capacity. Sorties 15 which had surged toward the MEUSE were beginning to withdraw, for the Claims (air) 1-0-0 v wily Rundstedt's best-laid plans had been wrecked on the rock of BAS "In addition to the tremendous quantities of mobile flak assigned TOGNS. -

Harry S. Truman As a Modern Cyrus

BYU Studies Quarterly Volume 34 Issue 1 Article 2 1-1-1994 Harry S. Truman as a Modern Cyrus Michael T. Benson Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq Part of the Mormon Studies Commons, and the Religious Education Commons Recommended Citation Benson, Michael T. (1994) "Harry S. Truman as a Modern Cyrus," BYU Studies Quarterly: Vol. 34 : Iss. 1 , Article 2. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq/vol34/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in BYU Studies Quarterly by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Benson: Harry S. Truman as a Modern Cyrus harry S truman with chaim weizmann truman officially received weizmann on may 25 1948 the first time the head of the new jewish state was received by a US president on that occasion weizmann acknowledged trumanstromansTrumans role in the recognition of israel by presenting him with a set oftorahof torah scrolls abba eban recalled that truman was not fully briefed by his staff not understanding what was within the purple velvet covering truman responded ive always wanted a set of these courtesy of the bettmann archive Published by BYU ScholarsArchive, 1994 1 BYU Studies Quarterly, Vol. 34, Iss. 1 [1994], Art. 2 harry S truman as a modern cyrus despite concerted opposition from his advisors who saw the move as strategically unwise truman ignored strategy and -

President Harry S Truman's Office Files, 1945–1953

A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of RESEARCH COLLECTIONS IN AMERICAN POLITICS Microforms from Major Archival and Manuscript Collections General Editor: William E. Leuchtenburg PRESIDENT HARRY S TRUMAN’S OFFICE FILES, 1945–1953 Part 2: Correspondence File UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of RESEARCH COLLECTIONS IN AMERICAN POLITICS Microforms from Major Archival and Manuscript Collections General Editor: William E. Leuchtenburg PRESIDENT HARRY S TRUMAN’S OFFICE FILES, 1945–1953 Part 2: Correspondence File Project Coordinators Gary Hoag Paul Kesaris Robert E. Lester Guide compiled by David W. Loving A microfilm project of UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA An Imprint of CIS 4520 East-West Highway • Bethesda, Maryland 20814-3389 LCCN: 90-956100 Copyright© 1989 by University Publications of America. All rights reserved. ISBN 1-55655-151-7. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ............................................................................................................................ v Scope and Content Note ....................................................................................................... xi Source and Editorial Note ..................................................................................................... xiii Reel Index Reel 1 A–Atomic Energy Control Commission, United Nations ......................................... 1 Reel 2 Attlee, Clement R.–Benton, William ........................................................................ 2 Reel 3 Bowles, Chester–Chronological -

Civillibertieshstlookinside.Pdf

Civil Liberties and the Legacy of Harry S. Truman The Truman Legacy Series, Volume 9 Based on the Ninth Truman Legacy Symposium The Civil Liberties Legacy of Harry S. Truman May 2011 Key West, Florida Edited by Richard S. Kirkendall Civil Liberties and the LEGACY of Harry S. Truman Edited by Richard S. Kirkendall Volume 9 Truman State University Press Copyright © 2013 Truman State University Press, Kirksville, Missouri, 63501 All rights reserved tsup.truman.edu Cover photo: President Truman delivers a speech on civil liberties to the American Legion, August 14, 1951 (Photo by Acme, copy in Truman Library collection, HSTL 76- 332). All reasonable attempts have been made to locate the copyright holder of the cover photo. If you believe you are the copyright holder of this photograph, please contact the publisher. Cover design: Teresa Wheeler Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Civil liberties and the legacy of Harry S. Truman / edited by Richard S. Kirkendall. pages cm. — (Truman legacy series ; 9) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-61248-084-8 (pbk. : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-1-61248-085-5 (ebook) 1. Truman, Harry S., 1884–1972—Political and social views. 2. Truman, Harry S., 1884–1972—Influence. 3. Civil rights—United States—History—20th century. 4. United States. Constitution. 1st–10th Amendments. 5. Cold War—Political aspects—United States. 6. Anti-communist movements—United States— History—20th century. 7. United States—Politics and government—1945–1953. I. Kirkendall, Richard Stewart, 1928– E814.C53 2013 973.918092—dc23 2012039360 No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any format by any means without written permission from the publisher. -

UCLA Historical Journal

s "They Never Stopped Watching Us": FBI Political Surveillance, 1924-1936 David Williams We never knew . about the way that Hoover ' FBI kept track of us after the 1924 reform an- nouncements. They never stopped watching us. — Roger Baldwin to Alan VJestin, 1977 '^ Since 1976, when the "Church Committee" uncovered a pattern of FBI abuses dating back to the 19 30s, considera- ble attention has focused on how the federal government can effectively control the FBI's domestic intelligence activities and prevent a resumption of widespread surveil- lance of lawful political activities. Legislation cur- rently before Congress proposes to charter the FBI and spells out in considerable detail the Bureau's criminal and intelligence responsibilities. While the Justice De- David Williams received his B.A. in History from Marquette University and completed his Ph.D. in modern American constitutional /legal his- tory at the University of New Hampshire. He is currently a student at Cornell University' s School of Law. 2 3 UCLA HISTORICAL JOURNAL partment and representatives of civil liberties and pro- fessional organizations are still debating the particu- lars, both sides share a common goal: an effective law enforcement agency which will not violate the law in pur- suit of its mission. This is the second major attempt in the Bureau's seventy-three year history to restrict FBI political sur- veillance. In May 1924, Attorney General Harlan Fiske Stone, armed with a mandate from President Calvin Coo- lidge to clean up the scandal-ridden Justice Department, ordered the Federal Bureau of Investigation to limit its investigations to violations of federal statutes. -

The Past Is a Foreign Country – Revisited David Lowenthal Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-85142-8 - The Past is a Foreign Country – Revisited David Lowenthal Frontmatter More information THE PAST IS A FOREIGN COUNTRY – REVISITED The past is past, but survives in and all around us, indispensable and inescap- able. Three decades after his classic The Past Is a Foreign Country, David Lowenthal re-examines why we love or loathe what seems old or familiar. His new book reveals how we know and remember the past, and the myriad ways – nostalgia or amnesia, restoration, replay, chauvinist celebration or remorseful contrition – we use and misuse it. We transform the past to serve present needs and future hopes, alike in preserving and in discarding what nature and our ancestors have handed down. Whether treasured boon or traumatic bane, the past is the prime source of personal and collective identity. Hence its relics and reminders evoke intense rivalry. Resurgent conflicts over history, memory, and heritage pervade every facet of public culture, making the foreign country of the past ever more our domesticated own. The past in the Internet age has become more intimate yet more remote, readily found but rapidly forgotten. Its range today is stupendous, embracing not just the human but the terrestrial and even the cosmic saga. And it is seen and touched and smelled as well as heard and read about. Traumatic recol- lection and empathetic re-enactment demote traditional history. A clear-cut chronicle certified by experts has become a fragmented congeries of contested relics, remnants and reminiscences. New insights into history and memory, bias and objectivity, artefacts and monuments, identity and authenticity, and remorse and contrition, make Lowenthal’s new book an essential key to the past that we inherit, reshape, and bequeath to the future. -

Introduction

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-85142-8 - The Past is a Foreign Country – Revisited David Lowenthal Excerpt More information Introduction The past is everywhere. All around us lie features with more or less familiar antecedents. Relics, histories, memories suffuse human experience. Most past traces ultimately perish, and all that remain are altered. But they are collectively enduring. Noticed or ignored, cherished or spurned, the past is omnipresent. ‘What is once done can never be undone ... Everything remains forever’, wrote Václav Havel, ‘somewhere here’.1 The past is not simply what has been saved; it ‘lives and breathes ...in every corner of the world’, adds a historian.2 A mass of memories and records, of relics and replicas, of monuments and memorabilia, sustains our being. We efface traces of tradition to assert our autonomy and expunge our errors, but the past inheres in all we do and think. Residues of bygone lives and locales ceaselessly enrich and inhibit our own. Awareness of things past comes less from fact finding than from feeling time’s impact on traits and traces, words and deeds of both our precursors and ourselves. To know we are ephemeral lessees of age-old hopes and dreams that have animated generations of endeavour secures our place – now to rejoice, now to regret – in the scheme of things. Ever more of the past, from the exceptional to the ordinary, from remote antiquity to barely yesterday, from the collective to the personal, is nowadays filtered by self- conscious appropriation. Such all-embracing heritage is scarcely distinguishable from past totality. -

Toward a Geographical History of Historical

Toward a Geographical History of Indiana: Landscape and Place in the Historical Imagination John A. Jakle “The muses care so little for geography.” Oscar Wilde, Sententiae Born at Terre Haute and graduated with a high school di- ploma from Culver Military Academy and a Ph.D. from Indiana University, I hold considerable affection for the Hoosier state. But it was in neighboring Michigan that I grew up, and for the past quarter century I have lived in adjacent Illinois, a professor of geography at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Al- though mine has tended to be the view of an outsider looking in, Indiana has always struck me as a distinctive place if only in its landscapes. Take, for example, what the watchful motorist can see upon entering Indiana from the north or the east. On the second- ary, or “blue highways,” rights-of-way tend to be narrower in Indi- ana, the roads not over-engineered with the wide sweeping curves and the monotonously level straightaways of Michigan and Illi- nois. In Indiana highways seem to fit more readily into the passing scene. Signs crowd the roads as do fences and, frequently, houses and other buildings (Figures 1 and 2). Except when seen from the freeways the Indiana countryside seems to be resisting modernism. There is a kinship with the past evident in the smaller scale of things, even new things, pushed close to Indiana roads. Could such differences be symptomatic of things profound? What might they mean to students of Indiana’s past? To me they have always suggested at the very least that In- diana may be more like Kentucky than its other neighbors. -

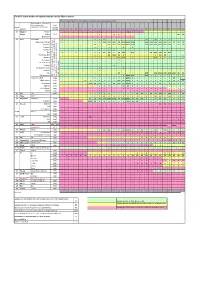

Proof of Reproduction of Salmon Returned to the Rhine System

Proof of reproduction of salmon returned to the Rhine system Year of spawning proof (reproduction during the preceding autumn/winter) Project water - Selection of the most important First Countr tributaries (* no stocking) salmon y System stocking 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 D Wupper- Wupper / / / / / / / / 0 / / / / / (X) / / / / / / / / / / X Dhünn Dhünn 1993 / / / / / / / / 0 / / X X / / / / / / / / / / / XX XX Eifgenbach / / / / / / / / / / / / 0 / / / / / / / / / / / / / D Sieg Sieg NRW X / / / / / / X 0 XX / / / / / / / / XX / XX 0 0 0 / / / Agger (lower 30 km) X / / / / / / 0 0 XXX XXX XXX XX XXXX XXXX XXXX / / XXX XXX XXX XXX XXX XX XX XX XX Naafbach / / / / / / / XX 0 / XXX XXX XXX XXXX XXXX XXXX / / XXX XXX XXX XXXX XXX XXX 0 XX XX Pleisbach / / / / / / / 0 / / 0 / / X / X / / / / / / / / / / Hanfbach / / / / / / / / 0 / 0 X / / / / / / / / / / / / / / Bröl X / / X / / / 0 0 XX XX 0 XX XXX / XXX / / / XX XXX XXX XX XXX / / Homburger Bröl / / / / / / / 0 0 / XX XXX XX X / / / / / / 0 XX XX 0 / / 0 Waldbröl / / / / / / / 0 0 / 0 0 XXX XXX / 0 / / / / XXX 0 0 0 / / 0 Derenbach / / / / / / / / / / / / 0 / / / / / / / / / / / / / Steinchesbach / / / / / / / / / / / / 0 / / / / / / / / / / / / / Krabach / / / / / / / / / / / X / / / / / / / / / / / / / / Gierzhagener Bach / / / / / / / / 0 / / / / X / / / / / / / / / / / / Irsenbach / / / / / / / / 0 / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / Sülz / / / / / / / 0 0 / / / XX / / / / / -

Die Natur in Der Luxemburger Moselregion Découvrir La Nature Dans La Région De La Experience the Natural Environment in the Erleben

Die Natur in der Luxemburger Moselregion Découvrir la nature dans la région de la Experience the natural environment in the erleben. Kanuausflüge auf Mosel und Sauer. Moselle luxembourgeoise. Excursions en Luxemburgish Moselle region. Canoe trips canoë sur la Moselle et la Sûre. on the Moselle and the Sauer. Das Kanuwandern als aktive Freizeitbeschäftigung steht jedem offen, La randonnée en canoë en tant qu’activité de loisirs est un sport Canoeing is an activity that can be enjoyed by everyone, be it in the ob auf der Mosel als gemächlicher Wanderfluss oder auf der Sauer mit ouvert à tous: que ce soit sur la Moselle, pour une excursion paisible, form of a leisurely excursion along the Mosel or a trip down the Sauer leichten Stromschnellen, ob jung oder alt, jeder kommt im Miseler- ou sur la Sûre avec ses légers rapides. Jeunes ou moins jeunes: dans la with its gentle rapids. Miselerland has something to offer for every- land auf seine Kosten! région du Miselerland, vous trouverez de quoi vous réjouir ! one whatever their age! DIE ANLEGESTELLEN LES POINTS D’ACCOSTAGE THE LANDING PLACES Dank den Anlegern entlang der Mosel und der Sauer, entscheiden Sie Grâce aux points d’accostage le long de la Moselle et de la Sûre, c’est Thanks to the landing places along the Mosel and the Sauer you can selbst an welchem Winzerort Sie einen Stopp einlegen. vous qui décidez dans quel village viticole vous allez faire une halte. choose in which viticulture village you like to stop. Entdecken Sie mit der ganzen Familie naturbelassene Seitentäler zu Découvrez à pied avec toute la famille les vallées adjacentes, qui You can discover the natural preserved lateral valleys by foot with Fuß, besichtigen Sie interessante Museen oder genießen Sie einfach ont conservé leur état naturel. -

Is Sark an Area “Of Particular Geopolitical Interest”? An

Is Sark an area “of particular Geopolitical Interest”? An interesting question. Here is a selection of what many international legal and geographical experts and expert bodies think. 1. Sark is on the UN M49 list and in the UNTERM database. 2. Sark is recognised by all levels of HMG including MoJ, FCO and DCMS. 3. The other government in the Bailiwick – The States of Guernsey – and their Law Officers recognise Sark, have confirmed it is separate and doesn’t come under their jurisdiction and legislature. 4. The EU acknowledges Sark’s individual status alongside other dependent territories within the negotiations over Brexit. 5. Sark is of sufficient geopolitical interest to be cited separately to and equivalent to other dependencies of the Crown in a decision of the International Court of Justice. The evidence in this case contains references to Sark dating back to the 12th century in international and legal documents. 6. The European Court of Human Rights decision of 1 Mar 2016 examined Sark’s constitutional position in exhaustive depth from 1202 to reach their determination and observes that it is “unquestionably unique in Europe”. 7. A dispute over fishing rights in the “Sark Box” resulted in the involvement of the French navy and British fishing inspectorate in 1996. 8. The Sark flag is flown at official UK State events and to mark Sark’s “Fief Day”. It is accorded equal status to those of the other governments of Crown Dependencies and BOTs. International flag authorities also confirm. 9. Sark’s relationship with the English Crown dates back to 1066 when William, Duke of Normandy invaded England.