Classification of Bantu Languages by Malcolm Guthrie Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Here Referred to As Class 18A (See Hyman 1980:187)

WS1 Remarks on the nasal classes in Mungbam and Naki Mungbam and Naki are two non-Grassfields Bantoid languages spoken along the northwest frontier of the Grassfields area to the north of the Ring languages. Until recently, they were poorly described, but new data reveals them to show significant nasal noun class patterns, some of which do not appear to have been previously noted for Bantoid. The key patterns are: 1. Like many other languages of their region (see Good et al. 2011), they make productive use of a mysterious diminutive plural prefix with a form like mu-, with associated concords in m, here referred to as Class 18a (see Hyman 1980:187). 2. The five dialects of Mungbam show a level of variation in their nasal classes that one might normally expect of distinct languages. a. Two dialects show no evidence for nasals in Class 6. Two other dialects, Munken and Ngun, show a Class 6 prefix on nouns of form a- but nasal concords. In Munken Class 6, this nasal is n, clearly distinct from an m associated with 6a; in Ngun, both 6 and 6a are associated with m concords. The Abar dialect shows a different pattern, with Class 6 nasal concords in m and nasal prefixes on some Class 6 nouns. b. The Abar, Biya, and Ngun dialects show a Class 18a prefix with form mN-, rather than the more regionally common mu-. This reduction is presumably connected to perseveratory nasalization attested throughout the languages of the region with a diachronic pathway along the lines of mu- > mũ- > mN- perhaps providing a partial example for the development of Bantu Class 9/10. -

Cover Page the Handle Holds Various Files of This Leiden University Dissertation. Author: Lima

Cover Page The handle http://hdl.handle.net/1887/85723 holds various files of this Leiden University dissertation. Author: Lima Santiago J. de Title: Zoonímia Histórico-comparativa: Denominações dos antílopes em bantu Issue Date: 2020-02-26 729 ANEXO 1: TABELA RECAPITULATIVA DAS PROTOFORMAS Nas protoformas provenientes do BLR (2003) e nas reconstruções de outros autores (majoritariamente, Mouguiama & Hombert, 2006), as classes nominais em negrito e sublinhadas, são sugestões da autora da tese. Significados Reconstruções Propostas Propostas do BLR e de de correções (De Lima outros autores Santiago) *-bʊ́dʊ́kʊ́ °-bʊ́dʊ́gʊ́ (cl. 9/10, 12/13) °-cénda (cl. 12/13) Philantomba °-cótɩ́ monticola (cl. 12/13) *-kùengà > °-kùèngà (cl. 11/5, 7/8) °°-cécɩ/ °°-cétɩ (cl. 9/10, 12/13) *-pàmbı ́ °-pàmbɩ́ (cl. 9/10) °-dòbò Cephalophus (cl. 3+9/4, nigrifrons 5/6) *-pùmbɩ̀dɩ̀ °-pùmbèèdɩ̀ (cl. 9/10, 9/6) 730 Significados Reconstruções Propostas Propostas do BLR e de de correções (De Lima outros autores Santiago) *-jʊ́mbɩ̀ (cl. 9/10, 3/4) °°-cʊ́mbɩ (cl. 9/10, 5/6, 7/8, 11/10) *-jìbʊ̀ °-tʊ́ndʊ́ Cephalophus (cl. 9/10) (cl. 9/10) silvicultor °°-bɩ́mbà °-bɩ̀mbà (cl. 9/10) °-kʊtɩ (cl. 9, 3) *-kʊ́dʊ̀pà/ °-bɩ́ndɩ́ *-kúdùpà (cl. 9/10, 7/8, (cl. 9/10) 3, 12/13) Cephalophus dorsalis °°-cíbʊ̀ °-pòmbɩ̀ (cl. 7/8) (cl. 9/10) °°-cʊmɩ >°-cʊmɩ́ °-gindà (cl. 9) Cephalophus (cl. 3/4) callipygus °°-cábè >°-cábà (cl. 9/10, 7/8) °°-bɩ̀jɩ̀ (cl. 9) 731 Significados Reconstruções Propostas Propostas do BLR e de de correções (De Lima outros autores Santiago) *-bengeda >°-bèngédè °-cégé (cl.9/10) (cl. 9/10) °°-àngàdà >°-jàngàdà Cephalophus (cl. -

Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics &A

Online Appendix for Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue (2014) Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics & Change Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue The following document lists the languages of the world and their as- signment to the macro-areas described in the main body of the paper as well as the WALS macro-area for languages featured in the WALS 2005 edi- tion. 7160 languages are included, which represent all languages for which we had coordinates available1. Every language is given with its ISO-639-3 code (if it has one) for proper identification. The mapping between WALS languages and ISO-codes was done by using the mapping downloadable from the 2011 online WALS edition2 (because a number of errors in the mapping were corrected for the 2011 edition). 38 WALS languages are not given an ISO-code in the 2011 mapping, 36 of these have been assigned their appropri- ate iso-code based on the sources the WALS lists for the respective language. This was not possible for Tasmanian (WALS-code: tsm) because the WALS mixes data from very different Tasmanian languages and for Kualan (WALS- code: kua) because no source is given. 17 WALS-languages were assigned ISO-codes which have subsequently been retired { these have been assigned their appropriate updated ISO-code. In many cases, a WALS-language is mapped to several ISO-codes. As this has no bearing for the assignment to macro-areas, multiple mappings have been retained. 1There are another couple of hundred languages which are attested but for which our database currently lacks coordinates. -

The Plymouth Brethren Medical Mission to Ikelenge, Northern Rhodesia Sarah Ponzer Northern Michigan University, [email protected]

Conspectus Borealis Volume 2 | Issue 1 Article 4 4-26-2017 "Disease, Wild Beasts, and Wilder Men": The Plymouth Brethren Medical Mission to Ikelenge, Northern Rhodesia Sarah Ponzer Northern Michigan University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.nmu.edu/conspectus_borealis Part of the African History Commons Recommended Citation Ponzer, Sarah (2017) ""Disease, Wild Beasts, and Wilder Men": The lyP mouth Brethren Medical Mission to Ikelenge, Northern Rhodesia," Conspectus Borealis: Vol. 2 : Iss. 1 , Article 4. Available at: https://commons.nmu.edu/conspectus_borealis/vol2/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals and Peer-Reviewed Series at NMU Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Conspectus Borealis by an authorized administrator of NMU Commons. For more information, please contact Kevin McDonough. 1 “DISEASE, WILD BEASTS, AND WILDER MEN”1: THE PLYMOUTH BRETHREN MEDICAL MISSION TO IKELENGE, NORTHERN RHODESIA 1 William Singleton Fisher and Julyan Hoyte, Ndotolu: The Life Stories of Walter and Anna Fisher of Central Africa (London, Pickering and Inglis, Ltd., 1987) pp. 21, Walter in a letter of correspondence with his mother about things they feared. 2 Introduction The Plymouth Brethren2 medical mission to the Ikelenge region of Northern Rhodesia, now Zambia, has many unique features. First, the Plymouth Brethren, a rebellious evangelical Christian denomination that formed in the 1800’s. Second, the founding physician of Kalene Mission Hospital, Dr. Walter Fisher, a surgeon who used unprecedented and revolutionary social tactics to incorporate local culture into his medical and personal life. Lastly, the cultural and linguistic aspects of the Lunda-Ndembu tribe3 that allowed for the assimilation of Lunda culture and beliefs into the lives and medical practices of the Brethren. -

Peace Corps Listing for the Pclive Knowledge Sharing Platform (Digital Knowledge Hub) Showing the Resources Available at Pclive, 2017

Description of document: Peace Corps listing for the PCLive knowledge sharing platform (digital knowledge hub) showing the resources available at PCLive, 2017 Requested date: July 2017 Release date: 21-December-2017 Posted date: 07-January-2019 Source of document: Freedom of Information Act Request FOIA Officer U.S. Peace Corps 1111 20th Street, NW Washington D.C. 20526 The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. Since 1961. December 21, 2017 RE: FOIA Request No. 17-0143 This is in response to your Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request. Specifically, "I request a copy of the table of contents, listing or index for the PCLive knowledge sharing platform ( digital knowledge hub), showing the 1200+ resources available at PCLive." Attached, you have a spreadsheet (1 sheet) listing PCLive resources. -

Options for a National Culture Symbol of Cameroon: Can the Bamenda Grassfields Traditional Dress Fit?

EAS Journal of Humanities and Cultural Studies Abbreviated Key Title: EAS J Humanit Cult Stud ISSN: 2663-0958 (Print) & ISSN: 2663-6743 (Online) Published By East African Scholars Publisher, Kenya Volume-2 | Issue-1| Jan-Feb-2020 | DOI: 10.36349/easjhcs.2020.v02i01.003 Research Article Options for a National Culture Symbol of Cameroon: Can the Bamenda Grassfields Traditional Dress Fit? Venantius Kum NGWOH Ph.D* Department of History Faculty of Arts University of Buea, Cameroon Abstract: The national symbols of Cameroon like flag, anthem, coat of arms and seal do not Article History in any way reveal her cultural background because of the political inclination of these signs. Received: 14.01.2020 In global sporting events and gatherings like World Cup and international conferences Accepted: 28.12.2020 respectively, participants who appear in traditional costume usually easily reveal their Published: 17.02.2020 nationalities. The Ghanaian Kente, Kenyan Kitenge, Nigerian Yoruba outfit, Moroccan Journal homepage: Djellaba or Indian Dhoti serve as national cultural insignia of their respective countries. The https://www.easpublisher.com/easjhcs reason why Cameroon is referred in tourist circles as a cultural mosaic is that she harbours numerous strands of culture including indigenous, Gaullist or Francophone and Anglo- Quick Response Code Saxon or Anglophone. Although aspects of indigenous culture, which have been grouped into four spheres, namely Fang-Beti, Grassfields, Sawa and Sudano-Sahelian, are dotted all over the country in multiple ways, Cameroon cannot still boast of a national culture emblem. The purpose of this article is to define the major components of a Cameroonian national culture and further identify which of them can be used as an acceptable domestic cultural device. -

Reglas De Congo: Palo Monte Mayombe) a Book by Lydia Cabrera an English Translation from the Spanish

THE KONGO RULE: THE PALO MONTE MAYOMBE WISDOM SOCIETY (REGLAS DE CONGO: PALO MONTE MAYOMBE) A BOOK BY LYDIA CABRERA AN ENGLISH TRANSLATION FROM THE SPANISH Donato Fhunsu A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English and Comparative Literature (Comparative Literature). Chapel Hill 2016 Approved by: Inger S. B. Brodey Todd Ramón Ochoa Marsha S. Collins Tanya L. Shields Madeline G. Levine © 2016 Donato Fhunsu ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Donato Fhunsu: The Kongo Rule: The Palo Monte Mayombe Wisdom Society (Reglas de Congo: Palo Monte Mayombe) A Book by Lydia Cabrera An English Translation from the Spanish (Under the direction of Inger S. B. Brodey and Todd Ramón Ochoa) This dissertation is a critical analysis and annotated translation, from Spanish into English, of the book Reglas de Congo: Palo Monte Mayombe, by the Cuban anthropologist, artist, and writer Lydia Cabrera (1899-1991). Cabrera’s text is a hybrid ethnographic book of religion, slave narratives (oral history), and folklore (songs, poetry) that she devoted to a group of Afro-Cubans known as “los Congos de Cuba,” descendants of the Africans who were brought to the Caribbean island of Cuba during the trans-Atlantic Ocean African slave trade from the former Kongo Kingdom, which occupied the present-day southwestern part of Congo-Kinshasa, Congo-Brazzaville, Cabinda, and northern Angola. The Kongo Kingdom had formal contact with Christianity through the Kingdom of Portugal as early as the 1490s. -

Essays on Cultural and Institutional Dynamics in Economic Development Using Spatial Analysis

Essays on Cultural and Institutional Dynamics in Economic Development Using Spatial Analysis by Timothy Birabi Submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Adam Smith Business School College of Social Sciences University of Glasgow April 2016 ©Timothy Birabi i Abstract This thesis seeks to research patterns of economic growth and development from a number of perspectives often resonated in the growth literature. By addressing themes about history, geography, institutions and culture the thesis is able to bring to bear a wide range of inter-related literatures and methodologies within a single content. Additionally, by targeting different administrative levels in its research design and approach, this thesis is also able to provide a comprehensive treatment of the economic growth dilemma from both cross- national and sub-national perspectives. The three chapters herein discuss economic development from two broad dimensions. The first of these chapters takes on the economic growth inquiry by attempting to incorporate cultural geography within a cross-country formal spatial econometric growth framework. By introducing the global cultural dynamics of languages and ethnic groups as spatial network mechanisms, this chapter is able to distinguish economic growth effects accruing from own-country productive efforts from those accruing from interconnections within a global productive network chain. From this, discussions and deductions about the implications for both developed and developing countries are made as regards potentials for gains and losses from such types and levels of productive integration. The second and third chapters take a different spin to the economic development inquiry. They both focus on economic activity in Africa, tackling the relevant issues from a geo-intersected dimension involving historic regional tribal homelands and modern national and subnational administrative territories. -

Central Africa, 2021 Region of Africa

Quickworld Entity Report Central Africa, 2021 Region of Africa Quickworld Factoid Name : Central Africa Status : Region of Africa Land Area : 7,215,000 sq km - 2,786,000 sq mi Political Entities Sovereign Countries (19) Angola Burundi Cameroon Central African Republic Chad Congo (DR) Congo (Republic) Equatorial Guinea Gabon Libya Malawi Niger Nigeria Rwanda South Sudan Sudan Tanzania Uganda Zambia International Organizations Worldwide Organizations (3) Commonwealth of Nations La Francophonie United Nations Organization Continental Organizations (1) African Union Conflicts and Disputes Internal Conflicts and Secessions (1) Lybian Civil War Territorial Disputes (1) Sudan-South Sudan Border Disputes Languages Language Families (9) Bihari languages Central Sudanic languages Chadic languages English-based creoles and pidgins French-based creoles and pidgins Manobo languages Portuguese-based creoles and pidgins Prakrit languages Songhai languages © 2019 Quickworld Inc. Page 1 of 7 Quickworld Inc assumes no responsibility or liability for any errors or omissions in the content of this document. The information contained in this document is provided on an "as is" basis with no guarantees of completeness, accuracy, usefulness or timeliness. Quickworld Entity Report Central Africa, 2021 Region of Africa Languages (485) Abar Acoli Adhola Aghem Ajumbu Aka Aka Akoose Akum Akwa Alur Amba language Ambele Amdang Áncá Assangori Atong language Awing Baali Babango Babanki Bada Bafaw-Balong Bafia Bakaka Bakoko Bakole Bala Balo Baloi Bambili-Bambui Bamukumbit -

Language Information LANGUAGE LINE

Language Information LANGUAGE LINE. The Court strongly prefers to use live interpreters in the courtrooms whenever possible. However, when the Court can’t find live interpreters, we sometimes use Language Line, a national telephone service supplying interpreters for most languages on the planet almost immediately. The number for that service is 1-800-874-9426. Contact Circuit Administration at 605-367-5920 for the Court’s account number and authorization codes. AMERICAN SIGN LANGUAGE/DEAF INTERPRETATION Minnehaha County in the 2nd Judicial Circuit uses a combination of local, highly credentialed ASL/Deaf interpretation providers including Communication Services for the Deaf (CSD), Interpreter Services Inc. (ISI), and highly qualified freelancers for the courts in Sioux Falls, Minnehaha County, and Canton, Lincoln County. We are also happy to make court video units available to any other courts to access these interpreters from Sioux Falls (although many providers have their own video units now). The State of South Dakota has also adopted certification requirements for ASL/deaf interpretation “in a legal setting” in 2006. The following link published by the State Department of Human Services/ Division of Rehabilitative Services lists all the certified interpreters in South Dakota and their certification levels, and provides a lot of other information on deaf interpretation requirements and services in South Dakota. DHS Deaf Services AFRICAN DIALECTS A number of the residents of the 2nd Judicial Circuit speak relatively obscure African dialects. For court staff, attorneys, and the public, this list may be of some assistance in confirming the spelling and country of origin of some of those rare African dialects. -

[.35 **Natural Language Processing Class Here Computational Linguistics See Manual at 006.35 Vs

006 006 006 DeweyiDecimaliClassification006 006 [.35 **Natural language processing Class here computational linguistics See Manual at 006.35 vs. 410.285 *Use notation 019 from Table 1 as modified at 004.019 400 DeweyiDecimaliClassification 400 400 DeweyiDecimali400Classification Language 400 [400 [400 *‡Language Class here interdisciplinary works on language and literature For literature, see 800; for rhetoric, see 808. For the language of a specific discipline or subject, see the discipline or subject, plus notation 014 from Table 1, e.g., language of science 501.4 (Option A: To give local emphasis or a shorter number to a specific language, class in 410, where full instructions appear (Option B: To give local emphasis or a shorter number to a specific language, place before 420 through use of a letter or other symbol. Full instructions appear under 420–490) 400 DeweyiDecimali400Classification Language 400 SUMMARY [401–409 Standard subdivisions and bilingualism [410 Linguistics [420 English and Old English (Anglo-Saxon) [430 German and related languages [440 French and related Romance languages [450 Italian, Dalmatian, Romanian, Rhaetian, Sardinian, Corsican [460 Spanish, Portuguese, Galician [470 Latin and related Italic languages [480 Classical Greek and related Hellenic languages [490 Other languages 401 DeweyiDecimali401Classification Language 401 [401 *‡Philosophy and theory See Manual at 401 vs. 121.68, 149.94, 410.1 401 DeweyiDecimali401Classification Language 401 [.3 *‡International languages Class here universal languages; general -

20180715205643 72921.Pdf

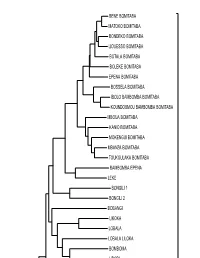

BENE BOMITABA MATOKO BOMITABA BONDEKO BOMITABA LIOUESSO BOMITABA BOTALA BOMITABA BOLEKE BOMITABA EPENA BOMITABA BOSSELA BOMITABA IBOLO BAMBOMBA BOMITABA KOUNDOUMOU BAMBOMBA BOMITABA MBOUA BOMITABA KANIO BOMITABA MOKENGUI BOMITABA MBANZA BOMITABA TOUKOULAKA BOMITABA BAMBOMBA EPENA LEKE BONGILI 1 BONGILI 2 BOBANGI LIKOKA LOBALA LOBALA LILOKA BOMBOMA LIBOBI LIBOBI LIFONGA ELEKU BONGINDA ELEKU IBENGE LINGALA 2 LINGALA NGOMBE LIKULA C36d LINGALA 2 C36e BOLOKI NGIRI BUJA MABALE ZAMBA BAMONGO ZAMBA 3 LIBINZA ZAMBA 2 ZAMBA ITANGA BOMITABA BABOLE DZEKE BABOLE IMPFONDO DZEKE DIBOLE MOUNDA DIBOLE KINAMI DIBOLE BOTONGO DIBOLE EDZAMA DIBOLE YAKA axk LINGOMBE 2 YAKA axk LINGOMBE 2 LINGOMBE NGOMBE DOKO EGBUTA BUJA BUMBA YAMOLOTO BUJA MONOGO BUMBA ESO YALEMBA MBESA TETELA YYONDO TETELA KUCU WELA ANKUTCU LOKELE YEPOLOMA LOKELE YALEMBA LOKELE YAWEMBE LOKELE ISANGI C75 KELA MONGO OPALA LOMONGO MONGO MONGO LOSAKANI NTOMBA C81 DENGESE SENGELE MBELO KONDA TWELIA NTOMBA DE BIKORO NTOMBA 2 NTOMBA DE BIKORO NTOMBA 2 NTOMBA BOLIA LONTOMBA BOLIA BANDUNDU BOLIA NSAO NTOMBA INONGO NTOMBA NJALE C24 KOYO ZWE KOYO EHAMBE MAKUA MBOSHI MBOSHI OLEE MBOSHI BUNJI MBOSHI NGOLO BAKUERI DUALA BATANGA BALUNDU KUNDU OROKO NGONDI ISONGO C10 GANDO BOGONGO PANDE C84 LELE LUHILEEL 2 C84 LELE LUHILEEL 2 C84 LELE LUHILEEL 4 C84 LELE LUHILEEL 3 C831 ILEBO WONGO 1 WONGO 2 BUSHOONG BUSHONG 1 BUSHONG 2 C80 MBINGI C80 SHUWA LAMBA MBOLE BALANGA LANGA MBOLE BAMBULI GENGELE KUSU KUSU MATAPA OMBO DUMA 2 TSAANGI NZEBI 1 NZEBI 2 IBONGO LAALI TEKE 1 IYAA LAALI TEKE 2 NDJABI NDJABI NDASA 1 NDASA