11Reclaiming the FLAG by Kyle Eidson with Dave Lachiondo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Connections Between Sámi and Basque Peoples

Connections between Sámi and Basque Peoples Kent Randell 2012 Siidastallan Outside of Minneapolis, Minneapolis Kent Randell (c) 2012 --- 2012 Siidastallan, Linwood Township, Minnesota Kent Randell (c) 2012 --- 2012 Siidastallan, Linwood Township, Minnesota “D----- it Jim, I’m a librarian and an armchair anthropologist??” Kent Randell (c) 2012 --- 2012 Siidastallan, Linwood Township, Minnesota Connections between Sámi and Basque Peoples Hard evidence: - mtDNA - Uniqueness of language Other things may be surprising…. or not. It is fun to imagine other connections, understanding it is not scientific Kent Randell (c) 2012 --- 2012 Siidastallan, Linwood Township, Minnesota Documentary: Suddenly Sámi by Norway’s Ellen-Astri Lundby She receives her mtDNA test, and express surprise when her results state that she is connected to Spain. This also surprised me, and spurned my interest….. Then I ended up living in Boise, Idaho, the city with the largest concentration of Basque outside of Basque Country Kent Randell (c) 2012 --- 2012 Siidastallan, Linwood Township, Minnesota What is mtDNA genealogy? The DNA of the Mitochondria in your cells. Cell energy, cell growth, cell signaling, etc. mtDNA – At Conception • The Egg cell Mitochondria’s DNA remains the same after conception. • Male does not contribute to the mtDNA • Therefore Mitochondrial mtDNA is the same as one’s mother. Kent Randell (c) 2012 --- 2012 Siidastallan, Linwood Township, Minnesota Kent Randell (c) 2012 --- 2012 Siidastallan, Linwood Township, Minnesota Kent Randell (c) 2012 --- 2012 Siidastallan, Linwood Township, Minnesota Four generation mtDNA line Sisters – Mother – Maternal Grandmother – Great-grandmother Jennie Mary Karjalainen b. Kent21 Randell March (c) 2012 1886, --- 2012 Siidastallan,parents from Kuusamo, Finland Linwood Township, Minnesota Isaac Abramson and Jennie Karjalainen wedding picture Isaac is from Northern Norway, Kvaen father and Saami mother from Haetta Kent Randell (c) 2012 --- 2012 Siidastallan, village. -

The Case of Eta

Cátedra de Economía del Terrorismo UNIVERSIDAD COMPLUTENSE DE MADRID Facultad de Ciencias Económicas y Empresariales DISMANTLING TERRORIST ’S ECONOMICS : THE CASE OF ETA MIKEL BUESA* and THOMAS BAUMERT** *Professor at the Universidad Complutense of Madrid. **Professor at the Catholic University of Valencia Documento de Trabajo, nº 11 – Enero, 2012 ABSTRACT This article aims to analyze the sources of terrorist financing for the case of the Basque terrorist organization ETA. It takes into account the network of entities that, under the leadership and oversight of ETA, have developed the political, economic, cultural, support and propaganda agenda of their terrorist project. The study focuses in particular on the periods 1993-2002 and 2003-2010, in order to observe the changes in the financing of terrorism after the outlawing of Batasuna , ETA's political wing. The results show the significant role of public subsidies in finance the terrorist network. It also proves that the outlawing of Batasuna caused a major change in that funding, especially due to the difficulty that since 2002, the ETA related organizations had to confront to obtain subsidies from the Basque Government and other public authorities. Keywords: Financing of terrorism. ETA. Basque Country. Spain. DESARMANDO LA ECONOMÍA DEL TERRORISMO: EL CASO DE ETA RESUMEN Este artículo tiene por objeto el análisis de las fuentes de financiación del terrorismo a partir del caso de la organización terrorista vasca ETA. Para ello se tiene en cuenta la red de entidades que, bajo el liderazgo y la supervisión de ETA, desarrollan las actividades políticas, económicas, culturales, de propaganda y asistenciales en las que se materializa el proyecto terrorista. -

Basque Studies N E W S L E T T E R

Center for BasqueISSN: Studies 1537-2464 Newsletter Center for Basque Studies N E W S L E T T E R Center welcomes Gloria Totoricagüena New faculty member Gloria Totoricagüena started to really compare and analyze their FALL began working at the Center last spring, experiences, to look at the similarities and having recently completed her Ph.D. in differences between that Basque Center and 2002 Comparative Politics. Following is an inter- Basque communities in the U.S. So that view with Dr. Totoricagüena by editor Jill really started my academic interest. Al- Berner. though my Master’s degree was in Latin American politics and economic develop- NUMBER 66 JB: How did your interest in the Basque ment, the experience there gave me the idea diaspora originate and develop? GT: I really was born into it, I’ve lived it all my life. My parents are survivors of the In this issue: bombing of Gernika and were refugees to different parts of the Basque Country. And I’ve also lived the whole sheepherder family Gloria Totoricagüena 1 experience that is so common to Basque identity in the U.S. My father came to the Eskerrik asko! 3 U.S. as a sheepherder, and then later went Slavoj Zizek lecture 4 back to Gernika where he met my mother and they married and came here. My parents went Politics after 9/11 5 back and forth actually, and eventually settled Highlights in Boise. So this idea of transnational iden- 6 tity, and multiculturalism, is not new at all to Visiting scholars 7 me. -

In Search of the Promised Land: the Travels of Emilia Pardo Bazan

IN SEARCH OF THE PROMISED LAND: THE TRAVELS OF EMILIA PARDO BAZAN Maria Gloria MUNOZ-MARTIN, University College London, Ph.D. in Spanish and Latin-American Studies, 2000 ProQuest Number: U642760 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest U642760 Published by ProQuest LLC(2015). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 ABSTRACT The object of this thesis is to explore Pardo Bazan's approach to travel as an aesthetically rewarding experience and also as a soul-searching exercise in which she voices her opinions and concerns with regard to the state of late nineteenth-century Spain and compares it to some other European countries. Indeed, in the Galician author's chronicles, which reveal her versatility and multifaceted interests as a travel writer, the journey itself takes second place to cultural, social, political, artistic, religious, and intellectual considerations. Another aspect of Pardo Bazan's travel works that this study will develop is her uneasy stance with regard to progress, technological advancement, and modern civilization, as illustrated, principally, in her foreign chronicles. For it is her apprehension and at times aversion to modern technology that place her in an anachronistic position in relation to some of the events and places covered in her travel accounts. -

The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre Their History and Their Traditions

Center for Basque Studies Basque Classics Series, No. 6 The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre Their History and Their Traditions by Philippe Veyrin Translated by Andrew Brown Center for Basque Studies University of Nevada, Reno Reno, Nevada This book was published with generous financial support obtained by the Association of Friends of the Center for Basque Studies from the Provincial Government of Bizkaia. Basque Classics Series, No. 6 Series Editors: William A. Douglass, Gregorio Monreal, and Pello Salaburu Center for Basque Studies University of Nevada, Reno Reno, Nevada 89557 http://basque.unr.edu Copyright © 2011 by the Center for Basque Studies All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America Cover and series design © 2011 by Jose Luis Agote Cover illustration: Xiberoko maskaradak (Maskaradak of Zuberoa), drawing by Paul-Adolph Kaufman, 1906 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Veyrin, Philippe, 1900-1962. [Basques de Labourd, de Soule et de Basse Navarre. English] The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre : their history and their traditions / by Philippe Veyrin ; with an introduction by Sandra Ott ; translated by Andrew Brown. p. cm. Translation of: Les Basques, de Labourd, de Soule et de Basse Navarre Includes bibliographical references and index. Summary: “Classic book on the Basques of Iparralde (French Basque Country) originally published in 1942, treating Basque history and culture in the region”--Provided by publisher. ISBN 978-1-877802-99-7 (hardcover) 1. Pays Basque (France)--Description and travel. 2. Pays Basque (France)-- History. I. Title. DC611.B313V513 2011 944’.716--dc22 2011001810 Contents List of Illustrations..................................................... vii Note on Basque Orthography......................................... -

Erabaki Eskubidea Helburu Elkarlanerako Prest, Modua Eta Denborak Adostu Behar

TERMOMETROA MARIAN BEITIALARRANGOITIA - MARKEL OLANO Erabaki eskubidea helburu elkarlanerako prest, modua eta denborak adostu behar Marian Beitialarrangoitia (Legazpi, 1968) EH Bilduko Eusko Legebiltzarreko parlamentaria eta Hernaniko alkate ohia da. Markel Olano (Beasain, 1965) EAJko biltzarkidea da Gipuzkoan eta lurraldeko diputatu nagusi ohia. Autogobernuaz jarduteko bildu ditugu. Adostasun nagusia: Euskal Herria subjektu politiko gisa eta bere erabaki eskubidea ordenamendu juridikoetan finkatu behar dira. Desadostasuna denboretan da. | XABIER LETONA | Argazkiak: Dani Blanco Autogobernuari begira hainbat urrats batean, burujabetza nahi hori estal- rretxe lehendakariak nahi izan zuen eman dira azken hamarkadetan Eus- tzeko egin zen. Urrats praktikoak erabaki eskubidea finkatu, hartutako kal Herrian. Non gaude orain? Zein da pentsatzeko aukera dugu orain. erabakiak gure borondatearen une honetan autogobernuaz egiten M. Olano: Momentu batean argi ondorio izan zitezen eta ez tresneria duzuen diagnostikoa? ikusi zen Gernikako Estatutua eta konstituzionalaren araberakoak. Markel Olano: Une honetan bada- Foru Hobekuntzaren bidetik egin- go autogobernuan urrats berri bat dako bideek ez zutela etorkizunik. Espainian eredu federalaz hitz egiten emateko aukera, bai Euskal Herrian Ibarretxe lehendakaria izan zen hori hasi da berriz. Espero duzue zerbait eta, lidergo puntu batekin, baita ikusarazi zuena. Berak orduan egin- hausnarketa horietatik? EAEn ere. Paraleloan, bakea jorra- dako diagnostikoak orain ere balio M. Beitialarrangoitia: Estatuaren tzeko aukera berriak ireki dira eta, du. Irakurketa hartan, zein zen aldetik ezin da ezer espero eta ez beraz, orain arte bai jarrera politiko- Espainiako ikuspegia euskal autogo- dut uste Estatuak benetako izaera an eta bai ikuspegi estrategikoan oso bernuari buruz? Estatua ez zen demokratikoa erakutsiko duenik. bereiziak ziren tradizio politikoak aldebiko ikuspegia jorratzen ari eta Aldebikotasunaz hitz egin duzu bateratzeko aukera dugu. -

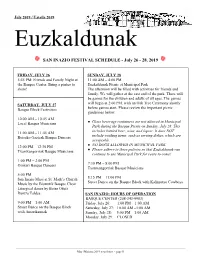

SAN INAZIO FESTIVAL SCHEDULE - July 26 - 28, 2019

1 July 2019 / Uztaila 2019 Euzkaldunak SAN INAZIO FESTIVAL SCHEDULE - July 26 - 28, 2019 FRIDAY, JULY 26 SUNDAY, JULY 28 5:45 PM: Friends and Family Night at 11:00 AM – 4:00 PM the Basque Center. Bring a pintxo to Euzkaldunak Picnic at Municipal Park share! The afternoon will be filled with activities for friends and family. We will gather at the east end of the park. There will be games for the children and adults of all ages. The games SATURDAY, JULY 27 will begin at 2:00 PM, with an Oak Tree Ceremony shortly Basque Block Festivities before games start. Please review the important picnic guidelines below: 10:00 AM – 10:45 AM ● Local Basque Musicians Glass beverage containers are not allowed in Municipal Park during the Basque Picnic on Sunday, July 28. This 11:00 AM – 11:45 AM includes bottled beer, wine, and liquor. It does NOT Boiseko Gazteak Basque Dancers include cooking items, such as serving dishes, which are acceptable. ● 12:00 PM – 12:30 PM NO DOGS ALLOWED IN MUNICIPAL PARK ● Txantxangorriak Basque Musicians Please adhere to these policies so that Euzkaldunak can continue to use Municipal Park for years to come! 1:00 PM – 2:00 PM Oinkari Basque Dancers 7:30 PM – 8:00 PM Txantxangorriak Basque Musicians 5:00 PM San Inazio Mass at St. Mark’s Church 8:15 PM – 11:00 PM Music by the Biotzetik Basque Choir Street Dance on the Basque Block with Kalimotxo Cowboys Liturgical dance by Boise Oñati Dantza Taldea SAN INAZIO: HOURS OF OPERATION BASQUE CENTER (208-343-9983) 9:00 PM – 1:00 AM Friday, July 26: 1:00 PM – 1:00 AM Street Dance on the Basque Block Saturday, July 27: 10:00 AM –1:00 AM with Amerikanuak Sunday, July 28: 5:00 PM – 1:00 AM Monday, July 29: CLOSED May /Maiatza 2019 newsletter - page 1 2 FRIENDS AND FAMILY NIGHT – JULY 26 Please join us as we kick off another great San Inazio Basque Festival Friday, July 26, at 5:45 PM. -

Pathways out of Violence Desecuritization and Legalization of Bildu and Sortu in the Basque Country Bourne, Angela

Roskilde University Pathways out of violence Desecuritization and legalization of Bildu and Sortu in the Basque Country Bourne, Angela Published in: Journal on Ethnopolitics and Minority Issues in Europe Publication date: 2018 Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Citation for published version (APA): Bourne, A. (2018). Pathways out of violence: Desecuritization and legalization of Bildu and Sortu in the Basque Country. Journal on Ethnopolitics and Minority Issues in Europe, 17(3), 45-66. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain. • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 01. Oct. 2021 Journal on Ethnopolitics and Minority Issues in Europe Vol 17, No 3, 2018, 45-66. Copyright © ECMI 2018 This article is located at: http://www.ecmi.de/fileadmin/downloads/publications/JEMIE/201 8/Bourne.pdf Pathways out of Violence: Desecuritization and Legalization of Bildu and Sortu in the Basque Country Angela Bourne Roskilde University Abstract In this article, I examine political processes leading to the legalization of the Batasuna- successor parties, Bildu and Sortu. -

How and Why Idaho Terminated Term Limits Scott .W Reed

Idaho Law Review Volume 50 | Number 3 Article 1 October 2014 How and Why Idaho Terminated Term Limits Scott .W Reed Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.uidaho.edu/idaho-law-review Recommended Citation Scott .W Reed, How and Why Idaho Terminated Term Limits, 50 Idaho L. Rev. 1 (2014). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.uidaho.edu/idaho-law-review/vol50/iss3/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ UIdaho Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Idaho Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ UIdaho Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HOW AND WHY IDAHO TERMINATED TERM LIMITS SCOTT W. REED1 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................. 1 II. THE 1994 INITIATIVE ...................................................................... 2 A. Origin of Initiatives for Term Limits ......................................... 3 III. THE TERM LIMITS HAVE POPULAR APPEAL ........................... 5 A. Term Limits are a Conservative Movement ............................. 6 IV. TERM LIMITS VIOLATE FOUR STATE CONSTITUTIONS ....... 7 A. Massachusetts ............................................................................. 8 B. Washington ................................................................................. 9 C. Wyoming ...................................................................................... 9 D. Oregon ...................................................................................... -

The Basque Experience with the Irish Model

WORKING PAPERS IN CONFLICT TRANSFORMATION AND SOCIAL JUSTICE ISSN 2053-0129 (Online) From Belfast to Bilbao: The Basque Experience with the Irish Model Eileen Paquette Jack, PhD Candidate School of Politics, International Studies and Philosophy, Queen’s University, Belfast [email protected] Institute for the Study of Conflict Transformation and Social Justice CTSJ WP 06-15 April 2015 Page | 1 Abstract This paper examines the izquierda Abertzale (Basque Nationalist Left) experience of the Irish model. Drawing upon conflict transformation scholars, the paper works to determine if the Irish model serves as a tool of conflict transformation. Using Interpretive Phenomenological Analysis (IPA), the paper argues that it is a tool, and focuses on the specific finding that it is one of many learning tools in the international sphere. It suggests that this theme can be generalized and could be found in other case studies. The paper is located within the discipline of peace and conflict studies, but uses a method from psychology. Keywords: Conflict transformation, Basque Country, Irish model, Peace Studies Introduction1 The conflict in the Basque Country remains one of the most intractable conflicts, and until recently was the only conflict within European borders. Euskadi Ta Askatasuna (ETA) has waged an open, violent conflict against the Spanish state, with periodic ceasefires and attempts for peace. Despite key differences in contexts, the izquierda Abertzale (‘nationalist left’) has viewed the Irish model – defined in this paper as a process of transformation which encompasses both the Good Friday Agreement (from here on referred to as GFA) and wider peace process in Northern Ireland – with potential. -

Comparing the Basque Diaspora

COMPARING THE BASQUE DIASPORA: Ethnonationalism, transnationalism and identity maintenance in Argentina, Australia, Belgium, Peru, the United States of America, and Uruguay by Gloria Pilar Totoricagiiena Thesis submitted in partial requirement for Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The London School of Economics and Political Science University of London 2000 1 UMI Number: U145019 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U145019 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Theses, F 7877 7S/^S| Acknowledgments I would like to gratefully acknowledge the supervision of Professor Brendan O’Leary, whose expertise in ethnonationalism attracted me to the LSE and whose careful comments guided me through the writing of this thesis; advising by Dr. Erik Ringmar at the LSE, and my indebtedness to mentor, Professor Gregory A. Raymond, specialist in international relations and conflict resolution at Boise State University, and his nearly twenty years of inspiration and faith in my academic abilities. Fellowships from the American Association of University Women, Euskal Fundazioa, and Eusko Jaurlaritza contributed to the financial requirements of this international travel. -

The Effect of Franco in the Basque Nation

Salve Regina University Digital Commons @ Salve Regina Pell Scholars and Senior Theses Salve's Dissertations and Theses Summer 7-14-2011 The Effect of Franco in the Basque Nation Kalyna Macko Salve Regina University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.salve.edu/pell_theses Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Macko, Kalyna, "The Effect of Franco in the Basque Nation" (2011). Pell Scholars and Senior Theses. 68. https://digitalcommons.salve.edu/pell_theses/68 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Salve's Dissertations and Theses at Digital Commons @ Salve Regina. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pell Scholars and Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Salve Regina. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Macko 1 The Effect of Franco in the Basque Nation By: Kalyna Macko Pell Senior Thesis Primary Advisor: Dr. Jane Bethune Secondary Advisor: Dr. Clark Merrill Macko 2 Macko 3 Thesis Statement: The combined nationalist sentiments and opposition of these particular Basques to the Fascist regime of General Franco explained the violence of the terrorist group ETA both throughout his rule and into the twenty-first century. I. Introduction II. Basque Differences A. Basque Language B. Basque Race C. Conservative Political Philosophy III. The Formation of the PNV A. Sabino Arana y Goiri B. Re-Introduction of the Basque Culture C. The PNV as a Representation of the Basques IV. The Oppression of the Basques A. Targeting the Basques B. Primo de Rivera C. General Francisco Franco D. Bombing of Guernica E.