Iva Nenić*1 'ROOTS in the Age of Youtube': OLD and CONTEMPORARY MODES of Learning / Teaching in Serbian Frula Playing From

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Intraoral Pressure in Ethnic Wind Instruments

Intraoral Pressure in Ethnic Wind Instruments Clinton F. Goss Westport, CT, USA. Email: [email protected] ARTICLE INFORMATION ABSTRACT Initially published online: High intraoral pressure generated when playing some wind instruments has been December 20, 2012 linked to a variety of health issues. Prior research has focused on Western Revised: August 21, 2013 classical instruments, but no work has been published on ethnic wind instruments. This study measured intraoral pressure when playing six classes of This work is licensed under the ethnic wind instruments (N = 149): Native American flutes (n = 71) and smaller Creative Commons Attribution- samples of ethnic duct flutes, reed instruments, reedpipes, overtone whistles, and Noncommercial 3.0 license. overtone flutes. Results are presented in the context of a survey of prior studies, This work has not been peer providing a composite view of the intraoral pressure requirements of a broad reviewed. range of wind instruments. Mean intraoral pressure was 8.37 mBar across all ethnic wind instruments and 5.21 ± 2.16 mBar for Native American flutes. The range of pressure in Native American flutes closely matches pressure reported in Keywords: Intraoral pressure; Native other studies for normal speech, and the maximum intraoral pressure, 20.55 American flute; mBar, is below the highest subglottal pressure reported in other studies during Wind instruments; singing. Results show that ethnic wind instruments, with the exception of ethnic Velopharyngeal incompetency reed instruments, have generally lower intraoral pressure requirements than (VPI); Intraocular pressure (IOP) Western classical wind instruments. This implies a lower risk of the health issues related to high intraoral pressure. -

Romanian Traditional Musical Instruments

GRU-10-P-LP-57-DJ-TR ROMANIAN TRADITIONAL MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS Romania is a European country whose population consists mainly (approx. 90%) of ethnic Romanians, as well as a variety of minorities such as German, Hungarian and Roma (Gypsy) populations. This has resulted in a multicultural environment which includes active ethnic music scenes. Romania also has thriving scenes in the fields of pop music, hip hop, heavy metal and rock and roll. During the first decade of the 21st century some Europop groups, such as Morandi, Akcent, and Yarabi, achieved success abroad. Traditional Romanian folk music remains popular, and some folk musicians have come to national (and even international) fame. ROMANIAN TRADITIONAL MUSIC Folk music is the oldest form of Romanian musical creation, characterized by great vitality; it is the defining source of the cultured musical creation, both religious and lay. Conservation of Romanian folk music has been aided by a large and enduring audience, and by numerous performers who helped propagate and further develop the folk sound. (One of them, Gheorghe Zamfir, is famous throughout the world today, and helped popularize a traditional Romanian folk instrument, the panpipes.) The earliest music was played on various pipes with rhythmical accompaniment later added by a cobza. This style can be still found in Moldavian Carpathian regions of Vrancea and Bucovina and with the Hungarian Csango minority. The Greek historians have recorded that the Dacians played guitars, and priests perform songs with added guitars. The bagpipe was popular from medieval times, as it was in most European countries, but became rare in recent times before a 20th century revival. -

Arhai's Balkan Folktronica: Serbian Ethno Music Reimagined for British

Ivana Medić Arhai’s Balkan Folktronica... DOI: 10.2298/MUZ1416105M UDK: 78.031.4 78.071.1:929 Бацковић Ј. Arhai’s Balkan Folktronica: Serbian Ethno Music Reimagined for British Market* Ivana Medić1 Institute of Musicology SASA (Belgrade) Abstract This article focuses on Serbian composer Jovana Backović and her band/project Arhai, founded in Belgrade in 1998. The central argument is that Arhai made a transition from being regarded a part of the Serbian ethno music scene (which flourished during the 1990s and 2000s) to becoming a part of the global world music scene, after Jovana Backović moved from her native Serbia to the United Kingdom to pursue an international career. This move did not imply a fundamental change of her musical style, but a change of cultural context and market conditions that, in turn, affected her cultural identity. Keywords Arhai, Jovana Backović, world music, ethno, Balkan Folktronica Although Serbian composer, singer and multi-instrumentalist Jovana Backović is only 34 years old, the band Arhai can already be considered her lifetime project. The Greek word ‘Arhai’ meaning ‘beginning’ or ‘ancient’ it is aptly chosen to summarise Backović’s artistic mission: rethinking tradition in contemporary context. Нer interest in traditional music was sparked by her father, himself a professional musician and performer of both traditional and popular folk music (Medić 2013). Backović founded Arhai in Belgrade in 1998, while still a pupil at music school Slavenski, and continued to perform with the band while receiving instruction in classical composition and orchestration at the Belgrade Faculty of Music. In its first, Belgrade ‘incarnation’, Arhai was a ten-piece band that developed a fusion of traditional music from the Balkans with am bient sounds and jazz-influenced improvisation, using both acoustic and electric instruments and a quartet of fe male vocalists. -

Mfmmmmi Ás 11 Horas Da Manhã De Hoie

" ææ__[.Redactor-chefo v, , — Dr. FERNANDO MENDES DE ALMEIDA*"/5^T*\ a =_==_===^jjj^jg., JAffJJ_Jg^~._.JH.arta"te:,ra 20 clc Agosto de 191 _TÇ^^^Hw724p~^ " olpó hordclrò Os leitores do Joriiol d' Danilo Alexandre. s'o,i ale fts io hora» da manha A LUQA-SB umn ama do leito uma moca 'pnECrSA-Sl. Brasil" quo corbtirom o opll.< çiirtua pnra o interior da Itepn- -^•'-Ititlliiii í, loas ALUGA-í---!-: portu- ,ie 111110. arruma- do uma criada; ^-nt^r^??.0.I*rl,u,1',BMr''u? 1'jlci até ás 10 l|_, de eonllfliSes', nn suexa pnra tavndcira e arru- -*• deira ca-a -1-pRECJSA-ÍSE nu- do umn orlada o cábèQallio deste jor l''\',-*',''? i;m rleiflénfffords, eom porte du- rua Vi-eoiiiU. Itauna n. li. lua.lelra de c-aiu; pura do peyuenn fa- rua ,1o lIoHplelo 335, sobrado. •_.;rapRECISA-SE ama secca pa. cclonarom Itissliip,77-, pio atê (lu 11 e objectos pura ro- na ruii Barão du iilillaj r, ,juu.,ui!ieii'o Thom :z e mais sorvIoCMl dias durante Baltlea, Kstlanlcr. coilhai glstriir C3.7SS S.ffl-oHx.lQC.(A. 52.08.) 53.285 leves; na Avenida Passos nal todos os o me: vido nrof(,-_or "Ilupoun",nt# fti, 0. (B, Coelho 51, Aldeia Campista. 'pitKri.SA.SK(B. 103.• do Rsthblloti s.nins, 50.202 51.18t • c trouxerem a collecção a est' -~ Pnlleee no Itecifc „ iuIm-ío- pur Pnrnn.1 o A 1.1'OA-Sl'! uma boa uma de A LI-GA-si-; unia uma secou do (A. -

Owner's Manual

BK-5_US.book Page 1 Monday, November 14, 2011 12:43 PM Owner’s Manual r BK-5_US.book Page 2 Monday, November 14, 2011 12:43 PM WARNING – To reduce the risk of fire or electric shock, do not expose this device to rain or moisture. ForFor EU EU Countriescountries This product complies with the requirements of European Directive EMC 2004/108/EC. ForFor the the USA USA FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION RADIO FREQUENCY INTERFERENCE STATEMENT This equipment has been tested and found to comply with the limits for a Class B digital device, pursuant to Part 15 of the FCC Rules. These limits are designed to provide reasonable protection against harmful interference in a residential installation. This equipment generates, uses, and can radiate radio frequency energy and, if not installed and used in accordance with the instructions, may cause harmful interference to radio communications. However, there is no guarantee that interference will not occur in a particular installation. If this equipment does cause harmful interference to radio or television reception, which can be determined by turning the equipment off and on, the user is encouraged to try to correct the interference by one or more of the following measures: — Reorient or relocate the receiving antenna. — Increase the separation between the equipment and receiver. — Connect the equipment into an outlet on a circuit different from that to which the receiver is connected. — Consult the dealer or an experienced radio/TV technician for help. This device complies with Part 15 of the FCC Rules. Operation is subject to the following two conditions: (1) This device may not cause harmful interference, and (2) This device must accept any interference received, including interference that may cause undesired operation. -

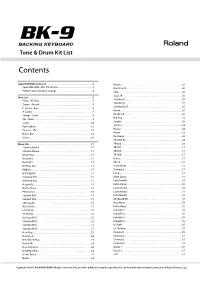

Tone & Drum Kit List

r Tone & Drum Kit List Contents SuperNATURAL Tone List . 3 Brush 2 . 24 SuperNATURAL INST Parameters . 3 Brush 2 L/R . 26 Performance Variation Sounds . 4 Jazz . .. 26 Jazz L/R . 26 Tone List . 5 Standard 1 . 26 Piano - E .Piano . 5 Standard 2 . 26 Organ - Accord . .. 5 Standard L/R . 26 E . Guitar - Bass . 6 Room . 26 A . Guitar . .. 7 Room L/R . 26 Strings - Vocal . 8 Hip Pop . 28 Sax - Brass . 9 Jungle . 28 Synth . 10 Techno . .28 Pad - Ethnic . 12 House . 28 Percuss - Sfx . 15 Power . 28 Harm . Bar . 16 Electronic . 28 Drums . 16 909 808 Kit . 28 Drum Kits . 17 TR-606 . 28 StandardNew1 . 17 TR-707 . 31 StandardNew2 . 17 TR-808 . 31 RoomNew . 17 TR-909 . 31 Rock Kit 1 . 17 Dance . 31 Rock Kit 2 . 17 CR-78 . 31 HipHop Kit 1 . 17 V-VoxDrum . 31 R&B Kit . 17 Orchestra . 31 HiFi R&B Kit . 17 Ethnic. 31 Machine Kit1 . 19 Multi Drum . 33 Machine Kit2 . 19 LatinDrmKit . .. 33 House Kit . 19 Latin Menu1 . 33 Nu Technica . .. 19 Latin Menu2 . 33 Percussion . 19 Latin Menu3 . 33 StudioX Kit1 . .19 IndiaDrmKit . .. 33 StudioX Kit2 . .19 MidEastDrKit . 33 SRX Studio . 19 Asia Menu . 33 WD Std Kit . 21 India Menu . .35 LD Std Kit . 21 IndoMix 1 . .. 35 TY Std Kit . 21 IndoMix 2 . .. 35 Kit-Euro:POP . 21 IndoMix 3 . .. 35 StandardKit1 . 21 IndoMix 4 . .. 35 StandardKit2 . 21 Or . R&B . 35 StandardKit3 . 21 Or . Techno . 35 New Pop . 21 Oriental 1 . 35 New Rock . 24 Oriental 2 . 37 New Brush Pop . 24 Oriental 3 . -

Serbia: Living Tradition

Tomka Paunović and Dragica Žunić by Predrag Todorović Music forms from The NationalRegistry of The Intangible Cultural Heritage of Serbia LIVING TRADITION Exhibition andExceptional Guide Roots to Music inSerbia SERBIA: LIVING TRADITION Exhibition and Guide to Exceptional Roots Music in Serbia Music forms from The National Registry of The Intangible Cultural Heritage of Serbia The project was supported by Republic of Serbia - The Ministry of Culture and Information Concept & realization by World Music Association of Serbia © 2020 / worldmusic.org.rs EXCEPTIONAL MUSICAL HERITAGE OF SERBIA he List of Elements of Intangible Cultural Heritage of the Republic of Serbia established by the TNational Committee for Intangible Cultural Heritage of Serbia currently includes 49 items (May 2020). The list was made in line with requirements of the UNESCO Convention for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage passed in 2003 and ratified by the National Assembly of the Republic of Serbia in 2010. his project, involving an exhibition with a guide, presents eight elements of the musical heritage Tof Serbia included in the List, that are of exceptional value for the culture of Serbia and the mankind. These are examples of the living vocal, vocal-instrumental and instrumental rural and urban musical traditions from various parts of Serbia. They are forms of musical expression the characteristics of which fit in with broader cultural and musical physiognomy of the area in which they are found. On the other, they are highly specific, even endemic, and therefore regarded as „trademark” forms for certain parts of Serbia (and thus for the country as a whole). Inclusion of these items in the national list confirms their value within the context of world folk music heritage. -

(EN) SYNONYMS, ALTERNATIVE TR Percussion Bells Abanangbweli

FAMILY (EN) GROUP (EN) KEYWORD (EN) SYNONYMS, ALTERNATIVE TR Percussion Bells Abanangbweli Wind Accordions Accordion Strings Zithers Accord‐zither Percussion Drums Adufe Strings Musical bows Adungu Strings Zithers Aeolian harp Keyboard Organs Aeolian organ Wind Others Aerophone Percussion Bells Agogo Ogebe ; Ugebe Percussion Drums Agual Agwal Wind Trumpets Agwara Wind Oboes Alboka Albogon ; Albogue Wind Oboes Algaita Wind Flutes Algoja Algoza Wind Trumpets Alphorn Alpenhorn Wind Saxhorns Althorn Wind Saxhorns Alto bugle Wind Clarinets Alto clarinet Wind Oboes Alto crumhorn Wind Bassoons Alto dulcian Wind Bassoons Alto fagotto Wind Flugelhorns Alto flugelhorn Tenor horn Wind Flutes Alto flute Wind Saxhorns Alto horn Wind Bugles Alto keyed bugle Wind Ophicleides Alto ophicleide Wind Oboes Alto rothophone Wind Saxhorns Alto saxhorn Wind Saxophones Alto saxophone Wind Tubas Alto saxotromba Wind Oboes Alto shawm Wind Trombones Alto trombone Wind Trumpets Amakondere Percussion Bells Ambassa Wind Flutes Anata Tarca ; Tarka ; Taruma ; Turum Strings Lutes Angel lute Angelica Percussion Rattles Angklung Mechanical Mechanical Antiphonel Wind Saxhorns Antoniophone Percussion Metallophones / Steeldrums Anvil Percussion Rattles Anzona Percussion Bells Aporo Strings Zithers Appalchian dulcimer Strings Citterns Arch harp‐lute Strings Harps Arched harp Strings Citterns Archcittern Strings Lutes Archlute Strings Harps Ardin Wind Clarinets Arghul Argul ; Arghoul Strings Zithers Armandine Strings Zithers Arpanetta Strings Violoncellos Arpeggione Keyboard -

Medium of Performance Thesaurus for Music

A clarinet (soprano) albogue tubes in a frame. USE clarinet BT double reed instrument UF kechruk a-jaeng alghōzā BT xylophone USE ajaeng USE algōjā anklung (rattle) accordeon alg̲hozah USE angklung (rattle) USE accordion USE algōjā antara accordion algōjā USE panpipes UF accordeon A pair of end-blown flutes played simultaneously, anzad garmon widespread in the Indian subcontinent. USE imzad piano accordion UF alghōzā anzhad BT free reed instrument alg̲hozah USE imzad NT button-key accordion algōzā Appalachian dulcimer lõõtspill bīnõn UF American dulcimer accordion band do nally Appalachian mountain dulcimer An ensemble consisting of two or more accordions, jorhi dulcimer, American with or without percussion and other instruments. jorī dulcimer, Appalachian UF accordion orchestra ngoze dulcimer, Kentucky BT instrumental ensemble pāvā dulcimer, lap accordion orchestra pāwā dulcimer, mountain USE accordion band satāra dulcimer, plucked acoustic bass guitar BT duct flute Kentucky dulcimer UF bass guitar, acoustic algōzā mountain dulcimer folk bass guitar USE algōjā lap dulcimer BT guitar Almglocke plucked dulcimer acoustic guitar USE cowbell BT plucked string instrument USE guitar alpenhorn zither acoustic guitar, electric USE alphorn Appalachian mountain dulcimer USE electric guitar alphorn USE Appalachian dulcimer actor UF alpenhorn arame, viola da An actor in a non-singing role who is explicitly alpine horn USE viola d'arame required for the performance of a musical BT natural horn composition that is not in a traditionally dramatic arará form. alpine horn A drum constructed by the Arará people of Cuba. BT performer USE alphorn BT drum adufo alto (singer) arched-top guitar USE tambourine USE alto voice USE guitar aenas alto clarinet archicembalo An alto member of the clarinet family that is USE arcicembalo USE launeddas associated with Western art music and is normally aeolian harp pitched in E♭. -

The MIT Folk Dance Club Songbook

The MIT Folk Dance Club Songbook Argentina VivaJujuy(Bailecito) ...................................... 1 Armenia Guhneega............................................. 2 Karun,karun........................................... 2 Darimena............................................. 3 Sirunakhchik(Sweetgirl).................................... 4 Assyrian Ainokchume........................................... 5 Bulgaria Hodih gore, hodih dolu (Cetvornoˇ ˇsopsko horo) . 6 SnoˇstisiRadapristana(Kjustendilskar˘uˇcenica). 7 Sadimoma............................................ 8 HodilamijeBojana(Pravo) .................................. 9 Gjurabelibeloplatno(Pajduˇsko). 9 Tr˘ugnalaRumjana........................................ 10 OkolPleven(Pravo)....................................... 11 Petruno,pileˇsareno ....................................... 12 MajkaRada(Pravo)....................................... 13 Karamfil ............................................. 13 Tr˘ugnal mi Jane Sandanski. 14 Molih ta, majˇco, i molih (Pravo). 14 Suvatarjakaodapriteˇce..................................... 15 Znzngankele(Pravo)...................................... 15 Kucinata.............................................. 16 Mjatalo Lenˇce jab˘ulka (R˘uˇcenica) . 17 Unaˇsetoselo........................................... 18 Trakijskar˘uˇcenica......................................... 19 Canada Labastringue........................................... 20 La Ziguezon (An dro). 21 Croatia Hopˇzicaˇzica........................................... 22 LepamojaMilena........................................ -

Dudy V Srbsku a Makedonii

Masarykova univerzita Filozofická fakulta Ústav hudební vědy Silvana Djokić Magisterská diplomová práce Dudy v Srbsku a Makedonii Vedoucí práce: prof. PhDr. Miloš Štědroň, CSc. Brno 2010 Prohlášení Prohlašuji, ţe jsem tuto práci vypracovala samostatně s pouţitím uvedených pramenů a literatury. Brno, 20. květen 2010 Silvana Djokić Obsah Předmluva .................................................................................................................. 1 Úvod ........................................................................................................................... 2 1. Etymologie .............................................................................................................. 5 2. Zařazení dud do systematik hudebních nástrojů .................................................... 8 3. Teritoriální vymezení dud v Srbsku a Makedonii ............................................... 111 3.1. Srbsko ...................................................................................................... 111 3.2. Makedonie .................................................................................................. 12 4. Organologický popis dud ...................................................................................... 15 4.1. Dudy v Srbsku ............................................................................................ 15 4.1.1. Dvojhlasé dudy ........................................................................................ 15 4.1.1.1. Vlašské dudy ....................................................................................... -

Flute Playing Physiology a Collection of Papers on the Physiological Effects of the Native American Flute

Flute Playing Physiology A Collection of Papers on the Physiological Effects of the Native American Flute Clint Goss Eric B. Miller Published on Flutopedia.com June 16, 2014 Copyright © 2014 by Clint Goss and Eric B. Miller. All Rights Reserved. 2 This collection of five papers reflects various aspects of research done on the physiological effects of the Native American flute. Versions of each of these papers have been published elsewhere. This table of Contents provides the citations of the five papers, as published, and a brief description of their intent and contents. Table of Contents [Goss 2014] Clint Goss and Eric B. Miller. “Your Brain on Flute”, Overtones, May 2014, published by the World Flute Society, pages 10–14. An article is intended to be accessible to a general audience. This article was edited by Kathleen Joyce- Grendahl. [Miller 2014] Eric B. Miller and Clinton F. Goss. “An Exploration of Physiological Responses to the Native American Flute”, ISQRMM 2013, Athens, Georgia, January 24, 2014, http://arxiv.org/abs/1401.6004. Also available in the Second Biennial Conference of the Interdisciplinary Society for Quantitative Research in Music and Medicine, Steve Jackowicz (editor), pages 95–143, ISBN 978-1-62266-036-7. This contains the full version of the results of our study, intended for the scientific community. [Miller 2014a] Eric B. Miller and Clinton F. Goss. “Trends in Physiological Metrics during Native American Flute Playing”, Nordic Journal of Music Therapy. April 29, 2014, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08098131.2014.908944 This is a pre-publication version of the article that appears in the Nordic Journal of Music Therapy.