Review Downloaded from by University of California, Irvine User on 18 March 2021 Performance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lectures and Community Engagement 2017–18 About the Metropolitan Opera Guild

Lectures and Community Engagement 2017 –18 About the Metropolitan Opera Guild The Metropolitan Opera Guild is the world’s premier arts educa- tion organization dedicated to enriching people’s lives through the magic and artistry of opera. Thanks to the support of individuals, government agencies, foundations, and corporate sponsors, the Guild brings opera to life both on and off the stage through its educational programs. For students, the Guild fosters personal expression, collaboration, literacy skills, and self-confidence with customized education programs integrated into the curricula of their schools. For adults, the Guild enhances the opera-going experience through intensive workshops, pre-performance talks, and community outreach programs. In addition to educational activities, the Guild publishes Opera News, the world’s leading opera magazine. With Opera News, the Guild reaches a global audience with the most insightful and up-to-date writing on opera available anywhere, helping to maintain opera as a thriving, contemporary art form. For more information about the Metropolitan Opera Guild and its programs, visit metguild.org. Additional information and archives of Opera News can be found online at operanews.com. How to Use This Booklet This brochure presents the 2017–18 season of Lectures and Community Programs grouped into thematic sections—programs that emphasize specific Met performances and productions; courses on opera and its history and culture; and editorial insights and interviews presented by our colleagues at Opera News. Courses of study are arranged chronologically, and learners of all levels are welcome. To place an order, please call the Guild’s ticketing line at 212.769.7028 (Mon–Fri 10AM–4PM). -

WORDS—A Collection of Poems and Song Lyrics by Paul F

WORDS— A Collection of Poems and Song Lyrics By P.F Uhlir Preface This volume contains the poems and songs I have written over the past four decades. There is a critical mass at his point, so I am self-publishing it online for others to see. It is still a work in progress and I will be adding to them as time goes on. The collections of both the poems and songs were written in different places with divergent topics and genres. It has been a sporadic effort, sometimes going for a decade without an inspiration and then several works in a matter of months. Although I have presented each collection chronologically, the pieces also could be arranged by themes. They are about love and sex, religion, drinking, and social topics—you know, the stuff to stay away from at the holiday table. In addition, although the songs only have lyrics, they can be grouped into genres such as blues, ballads, and songs that would be appropriate in musicals. Some of the songs defy categorization. I have titled the collection “Words”, after my favorite poem, which is somewhere in the middle. Most of them tell a story about a particular person, or event, or place that is meaningful to me. It is of personal significance and perhaps not interesting or understandable to the reader. To that extent, it can be described as a self-indulgence or an introspection; but most of them are likely to have a broader meaning that can be readily discerned. I’m sure I will add to them as time goes on, but I felt it was time to put them out. -

Sally Matthews Is Magnificent

` DVORAK Rusalka, Glyndebourne Festival, Robin Ticciati. DVD Opus Arte Sally Matthews is magnificent. During the Act II court ball her moral and social confusion is palpable. And her sorrowful return to the lake in the last act to be reviled by her water sprite sisters would melt the winter ice. Christopher Cook, BBC Music Magazine, November 2020 Sally Matthews’ Rusalka is sung with a smoky soprano that has surprising heft given its delicacy, and the Prince is Evan LeRoy Johnson, who combines an ardent tenor with good looks. They have great chemistry between them and the whole cast is excellent. Opera Now, November-December 2020 SCHUMANN Paradies und die Peri, Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra, Paolo Bortolameolli Matthews is noted for her interpretation of the demanding role of the Peri and also appears on one of its few recordings, with Rattle conducting. The soprano was richly communicative in the taxing vocal lines, which called for frequent leaps and a culminating high C … Her most rewarding moments occurred in Part III, particularly in “Verstossen, verschlossen” (“Expelled again”), as she fervently Sally Matthews vowed to go to the depths of the earth, an operatic tour-de-force. Janelle Gelfand, Cincinnati Business Courier, December 2019 Soprano BARBER Two Scenes from Anthony & Cleopatra, Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Juanjo Mena This critic had heard a fine performance of this music by Matthews and Mena at the BBC Proms in London in 2018, but their performance here on Thursday was even finer. Looking suitably regal in a glittery gold form-fitting gown, the British soprano put her full, vibrant, richly contoured voice fully at the service of text and music. -

Buffy's Glory, Angel's Jasmine, Blood Magic, and Name Magic

Please do not remove this page Giving Evil a Name: Buffy's Glory, Angel's Jasmine, Blood Magic, and Name Magic Croft, Janet Brennan https://scholarship.libraries.rutgers.edu/discovery/delivery/01RUT_INST:ResearchRepository/12643454990004646?l#13643522530004646 Croft, J. B. (2015). Giving Evil a Name: Buffy’s Glory, Angel’s Jasmine, Blood Magic, and Name Magic. Slayage: The Journal of the Joss Whedon Studies Association, 12(2). https://doi.org/10.7282/T3FF3V1J This work is protected by copyright. You are free to use this resource, with proper attribution, for research and educational purposes. Other uses, such as reproduction or publication, may require the permission of the copyright holder. Downloaded On 2021/10/02 09:39:58 -0400 Janet Brennan Croft1 Giving Evil a Name: Buffy’s Glory, Angel’s Jasmine, Blood Magic, and Name Magic “It’s about power. Who’s got it. Who knows how to use it.” (“Lessons” 7.1) “I would suggest, then, that the monsters are not an inexplicable blunder of taste; they are essential, fundamentally allied to the underlying ideas of the poem …” (J.R.R. Tolkien, “Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics”) Introduction: Names and Blood in the Buffyverse [1] In Joss Whedon’s Buffy the Vampire Slayer (1997-2003) and Angel (1999- 2004), words are not something to be taken lightly. A word read out of place can set a book on fire (“Superstar” 4.17) or send a person to a hell dimension (“Belonging” A2.19); a poorly performed spell can turn mortal enemies into soppy lovebirds (“Something Blue” 4.9); a word in a prophecy might mean “to live” or “to die” or both (“To Shanshu in L.A.” A1.22). -

The Death of the Angel: Reflections on the Relationship Between Enlighten- Ment and Enchantment in the Twenty-First Century1

The Death of the Angel: Reflections on the Relationship between Enlighten- ment and Enchantment in the Twenty-first Century1 RUTH BEHAR University ()/Michigan Abstract Tango artist Astor Piazzolla's composition/ 'La muerte del ángel', serves as inspiration for a few reflections on the relationship between enlightenment and enchantment in the 21st cenhrry. Piazzolla wrote the fugue as accompaniment to a play, 'Tango del angel', about an angel who tries to heal broken human spirits in Buenos Aires and ends up dying in a knife fight. Drawing on tango's melancholy, longing, and hesitant hoping, 1 share stories from my travels where 1 engage with the straggle to sustain an ethnographic art that brings heart to the process of knowing the world. Keywords: ethnography, reflexivity, tango, writing The tango, a form of music, song, and dance, as well as a sensibility, a way of being in the world, was bom in Argentina. But 1 first heard the tango and felt it and fell in love with it in Cuba, my native land. Daniel Esquenazi Maya, an old and impoverished man who lived in a rooftop apartment in Old Havana, gave me my first introduction to the tango. Daniel was one among a handful of Jews who didn't want to be uprooted and stayed in Cuba after the Revolution that brought Fidel Castro to power in 1959. Most Jews left soon afterward. The Communist expropriation of properties, stores, businesses, and miniature enterprises, tike door-to-door street peddling, on which many Jews depended for their livelihood, led to a mass exodus ftom Cuba. -

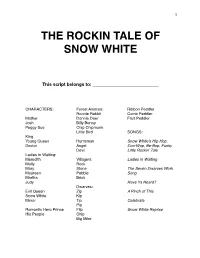

Rockin Snow White Script

!1 THE ROCKIN TALE OF SNOW WHITE This script belongs to: __________________________ CHARACTERS: Forest Animals: Ribbon Peddler Roonie Rabbit Comb Peddler Mother Donnie Deer Fruit Peddler Josh Billy Bunny Peggy Sue Chip Chipmunk Little Bird SONGS: King Young Queen Huntsman Snow White’s Hip-Hop, Doctor Angel Doo-Wop, Be-Bop, Funky Devil Little Rockin’ Tale Ladies in Waiting: Meredith Villagers: Ladies in Waiting Molly Rock Mary Stone The Seven Dwarves Work Maureen Pebble Song Martha Brick Judy Have Ya Heard? Dwarves: Evil Queen Zip A Pinch of This Snow White Kip Mirror Tip Celebrate Pip Romantic Hero Prince Flip Snow White Reprise His People Chip Big Mike !2 SONG: SNOW WHITE HIP-HOP, DOO WOP, BE-BOP, FUNKY LITTLE ROCKIN’ TALE ALL: Once upon a time in a legendary kingdom, Lived a royal princess, fairest in the land. She would meet a prince. They’d fall in love and then some. Such a noble story told for your delight. ’Tis a little rockin’ tale of pure Snow White! They start rockin’ We got a tale, a magical, marvelous, song-filled serenade. We got a tale, a fun-packed escapade. Yes, we’re gonna wail, singin’ and a-shoutin’ and a-dancin’ till my feet both fail! Yes, it’s Snow White’s hip-hop, doo-wop, be-bop, funky little rockin’ tale! GIRLS: We got a prince, a muscle-bound, handsome, buff and studly macho guy! GUYS: We got a girl, a sugar and spice and-a everything nice, little cutie pie. ALL: We got a queen, an evil-eyed, funkified, lean and mean, total wicked machine. -

Quaking Bankers

the grand jury nor the fact that any [claimed by the plaintiffs to lie acbool a indictment for felony has been found and Indemnity lands arc in n dity TIS BANKERS against MARRIED BADGER DAY CHINESE MUST GO QUAKING any person not in custody .>r DR. SHAW IS swamp contention ot under recognizance; you are to present lands The main no man for envy, hatred or malice; th* plaintltfs attorneys will lie that tin neither an you to leave any man u.i- no to -el ii MILWAUKEE GRAND JURY l I' NOB THE legislature has power aside 'VI \IR o\ To ix;i; ivoss has a mind ok his allK presented for love, fear, favor, MISS BESSIE LA'‘ON *RI.I is I I I RNKD ER ■ affection sclhk'l lauds from sale. The order will or hope of reward. But it becomes GOES TO WORK. " ISO INSIN PFOPI i: OWN. your duty to investigate carefully and EDITORS BRIDE. Is* made when the attorneys agree impartially the matters given you in as to what circuit court shall try the charge things and to present truly as ease, the attorney general preferring they may have come to your know! ( AI.iIOUNIAN MAM'S AN JUDGE WAIJ.BKR DELIVERS A THE CEREMONY TAKES PLACE AT the Dane county -court, while the GREAT TIItt'VDS Wild THRONG no. IM edge, according to the best of your mi- llerstun ding.” plaint tfs attorneys. Messrs Hilton SWEEPING CHARGE. READING. F V THE EXPOSITION GROUNDS. KttKTANT 111 UNO Disrtr. ’ Attorney says llaminel that and 1 ullar, wish to take it to Wan all Milwaukee attorneys of any stand- ing are comnvtod w;h bank cases and kesha ounty. -

ANIOŁ ZAGŁADY THOMAS ADÈS Dyrektor Naczelny Tomasz Bęben Dyrektor Artystyczny Paweł Przytocki Chórmistrz, Szef Chóru Dawid Ber

ANIOŁ ZAGŁADY THOMAS ADÈS dyrektor naczelny Tomasz Bęben dyrektor artystyczny Paweł Przytocki chórmistrz, szef chóru Dawid Ber dyrektor generalny Peter Gelb honorowy dyrektor muzyczny James Levine dyrektor muzyczny Yannick Nézet-Séguin główny dyrygent Fabio Luisi 2. ANIOŁ ZAGŁADY (THE EXTERMINATING ANGEL) OPERA W TRZECH AKTACH LIBRETTO: TOM CAIRNS WE WSPÓŁPRACY Z KOMPOZYTOREM NA PODSTAWIE FILMU LUISA BUÑUELA POD TYM SAMYM TYTUŁEM OSOBY Lucía, markiza de Nobile, gospodyni sopran Leticia Maynar, śpiewaczka operowa sopran koloraturowy Leonora Palma mezzosopran Silvia, hrabina Ávila, młoda owdowiała matka sopran Blanca Delgado, pianistka, żona Roca mezzosopran Beatriz, narzeczona Eduarda sopran Edmundo, markiz de Nobile, gospodarz tenor hrabia Raúl Yebenes, odkrywca tenor pułkownik Álvaro Gómez baryton Francisco de Ávila, brat Silvii kontratenor Eduardo, narzeczony Beatriz tenor Señor Russell bas-baryton Alberto Roc, dyrygent bas-baryton Doktor Carlos Conde bas Julio, kamerdyner baryton Lucas, lokaj tenor Enrique, kelner tenor Pablo, kucharz baryton Meni, pokojówka sopran Camila, pokojówka mezzosopran Padre Sansón baryton Yoli, synek Silvii dyszkant chłopięcy Chór (SABT) grający służących, policjantów, wojskowych, tłum Prapremiera podczas Salzburger Festspiele – 28 lipca 2016 roku Premiera inscenizacji w The Metropolitan Opera w Nowym Jorku – 26 października 2017 roku Współpraca i koprodukcja Metropolitan Opera, Royal Opera House Covent Garden, Royal Danish Theatre i Salzburg Festival Transmisja z The Metropolitan Opera w Nowym Jorku – 18 -

Slayage, Number 16

Roz Kaveney A Sense of the Ending: Schrödinger's Angel This essay will be included in Stacey Abbott's Reading Angel: The TV Spinoff with a Soul, to be published by I. B. Tauris and appears here with the permission of the author, the editor, and the publisher. Go here to order the book from Amazon. (1) Joss Whedon has often stated that each year of Buffy the Vampire Slayer was planned to end in such a way that, were the show not renewed, the finale would act as an apt summation of the series so far. This was obviously truer of some years than others – generally speaking, the odd-numbered years were far more clearly possible endings than the even ones, offering definitive closure of a phase in Buffy’s career rather than a slingshot into another phase. Both Season Five and Season Seven were particularly planned as artistically satisfying conclusions, albeit with very different messages – Season Five arguing that Buffy’s situation can only be relieved by her heroic death, Season Seven allowing her to share, and thus entirely alleviate, slayerhood. Being the Chosen One is a fatal burden; being one of the Chosen Several Thousand is something a young woman might live with. (2) It has never been the case that endings in Angel were so clear-cut and each year culminated in a slingshot ending, an attention-grabber that kept viewers interested by allowing them to speculate on where things were going. Season One ended with the revelation that Angel might, at some stage, expect redemption and rehumanization – the Shanshu of the souled vampire – as the reward for his labours, and with the resurrection of his vampiric sire and lover, Darla, by the law firm of Wolfram & Hart and its demonic masters (‘To Shanshu in LA’, 1022). -

Buffy & Angel Watching Order

Start with: End with: BtVS 11 Welcome to the Hellmouth Angel 41 Deep Down BtVS 11 The Harvest Angel 41 Ground State BtVS 11 Witch Angel 41 The House Always Wins BtVS 11 Teacher's Pet Angel 41 Slouching Toward Bethlehem BtVS 12 Never Kill a Boy on the First Date Angel 42 Supersymmetry BtVS 12 The Pack Angel 42 Spin the Bottle BtVS 12 Angel Angel 42 Apocalypse, Nowish BtVS 12 I, Robot... You, Jane Angel 42 Habeas Corpses BtVS 13 The Puppet Show Angel 43 Long Day's Journey BtVS 13 Nightmares Angel 43 Awakening BtVS 13 Out of Mind, Out of Sight Angel 43 Soulless BtVS 13 Prophecy Girl Angel 44 Calvary Angel 44 Salvage BtVS 21 When She Was Bad Angel 44 Release BtVS 21 Some Assembly Required Angel 44 Orpheus BtVS 21 School Hard Angel 45 Players BtVS 21 Inca Mummy Girl Angel 45 Inside Out BtVS 22 Reptile Boy Angel 45 Shiny Happy People BtVS 22 Halloween Angel 45 The Magic Bullet BtVS 22 Lie to Me Angel 46 Sacrifice BtVS 22 The Dark Age Angel 46 Peace Out BtVS 23 What's My Line, Part One Angel 46 Home BtVS 23 What's My Line, Part Two BtVS 23 Ted BtVS 71 Lessons BtVS 23 Bad Eggs BtVS 71 Beneath You BtVS 24 Surprise BtVS 71 Same Time, Same Place BtVS 24 Innocence BtVS 71 Help BtVS 24 Phases BtVS 72 Selfless BtVS 24 Bewitched, Bothered and Bewildered BtVS 72 Him BtVS 25 Passion BtVS 72 Conversations with Dead People BtVS 25 Killed by Death BtVS 72 Sleeper BtVS 25 I Only Have Eyes for You BtVS 73 Never Leave Me BtVS 25 Go Fish BtVS 73 Bring on the Night BtVS 26 Becoming, Part One BtVS 73 Showtime BtVS 26 Becoming, Part Two BtVS 74 Potential BtVS 74 -

Angel in My Heart 09/14 Revise3 P

09/14 revise3 p. 1 of 69 Angel in my Heart 09/14 revise3 p. 2 of 69 ANGEL IN MY HEART a musical romance The set is divided into two parts: one part suggests the men's departments at various expensive New York department stores; the other area represents a copywriter's office at a fragrance company, with ergonomic chair, desk and computer. Other settings are suggested throughout. ACT ONE - Scene i - THE MENʼS DEPARTMENT OF BERGDORF GOODMAN'S. BRIAN HAYES, early 30ʼs and immaculately handsome, is trying on a designer sport jacket when BERNIE LICHTENBERG, same age, enters in a frazzle. BERNIE [recitative: I know Iʼm late…] I KNOW, I KNOW! IʼM LATE, BUT YOU CAN THANK YOUR LUCKY STARS IʼM HERE AT ALL. I BARELY MADE IT THROUGH THE FRAGRANCE DEPARTMENT. WHAT DʼYA CALLIT — the pretty people with the samples ... BRIAN ATTACK MODELS. STINK BOMBERS… BERNIE YEH. THEM. THEYʼRE ON THE RAMPAGE — Iʼve been spritzed by Ralph, Calvin and three Europeans Iʼve never heard of. If I put my wrist too near my nose, Iʼll pass out from the fumes. BRIAN So donʼt sniff your wrist. BERNIE AND ALL THOSE “CHAYAS” PUSHING AND SHOVING, FIGHTING OVER THE CASHMERE SWEATERS. WHO KNEW YOU COULD GET BLACK AND BLUE FROM CASHMERE? I had to threaten a lawsuit to get at the beige crew neck I had my eye on. Youʼd think people would be more civilized at Bergdorfʼs. BRIAN SOMETIMES YOUʼVE GOTTA BE AGGRESSIVE AND GO AFTER WHAT YOU WANT. THATʼS THE EXCITEMENT OF SHOPPING: THE THRILL OF THE HUNT. -

Devil Or Angel? the Role of Speculation in the Recent Commodity Price Boom

Devil or Angel? The Role of Speculation in the Recent Commodity Price Boom Scott H. Irwin Monthly Average Price of Crude Oil, Cushing, OK, Jan 2000 - Oct 2008 140 120 100 80 76 60 40 Crude Oil Price ($/bbl.) Crude 20 0 Jan-00 Jan-01 Jan-02 Jan-03 Jan-04 Jan-05 Jan-06 Jan-07 Jan-08 Monthly Farm Price of Corn in Illinois, Jan 2000 - Oct 2008 6.00 5.00 4.00 4.00 3.00 Price ($/bu.) 2.00 1.00 Jan-00 Jan-01 Jan-02 Jan-03 Jan-04 Jan-05 Jan-06 Jan-07 Jan-08 Monthly RJ/CRB Commodity Price Index, Jan 2000 - Oct 2008 500 400 300 267 200 Index (Jan. 1982 = 100) 100 Jan-00 Jan-01 Jan-02 Jan-03 Jan-04 Jan-05 Jan-06 Jan-07 Jan-08 When you have enough speculators betting on the rising price of oil, that itself can cause oil prices to keep on rising. And while a few reckless speculators are counting their paper profits, most Americans are coming up on the short end — using more and more of their hard-earned paychecks to buy gas for the truck, tractor, or family car. Investigation is underway to root out this kind of reckless wagering, unrelated to any kind of productive commerce, because it can distort the market, drive prices beyond rational limits, and put the investments and pensions of millions of Americans at risk. Where we find such abuses, they need to be swiftly punished. ---U.S. Senator John McCain, June 18, 2008 "For the past years, our energy policy in this country has been simply to let the special interests have their way -- opening up loopholes for the oil companies and speculators so that they could reap record profits while the rest of us pay $4 a gallon," ---U.S.