The Death of the Angel: Reflections on the Relationship Between Enlighten- Ment and Enchantment in the Twenty-First Century1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WORDS—A Collection of Poems and Song Lyrics by Paul F

WORDS— A Collection of Poems and Song Lyrics By P.F Uhlir Preface This volume contains the poems and songs I have written over the past four decades. There is a critical mass at his point, so I am self-publishing it online for others to see. It is still a work in progress and I will be adding to them as time goes on. The collections of both the poems and songs were written in different places with divergent topics and genres. It has been a sporadic effort, sometimes going for a decade without an inspiration and then several works in a matter of months. Although I have presented each collection chronologically, the pieces also could be arranged by themes. They are about love and sex, religion, drinking, and social topics—you know, the stuff to stay away from at the holiday table. In addition, although the songs only have lyrics, they can be grouped into genres such as blues, ballads, and songs that would be appropriate in musicals. Some of the songs defy categorization. I have titled the collection “Words”, after my favorite poem, which is somewhere in the middle. Most of them tell a story about a particular person, or event, or place that is meaningful to me. It is of personal significance and perhaps not interesting or understandable to the reader. To that extent, it can be described as a self-indulgence or an introspection; but most of them are likely to have a broader meaning that can be readily discerned. I’m sure I will add to them as time goes on, but I felt it was time to put them out. -

Review Downloaded from by University of California, Irvine User on 18 March 2021 Performance

Review Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/oq/article/34/4/355/5469296 by University of California, Irvine user on 18 March 2021 Performance Review Colloquy: The Exterminating Angel Met Live in HD, November 18, 2017 Music: Thomas Ade`s Libretto: Tom Cairns, in collaboration with the composer, based on the screenplay by Luis Bunuel~ and Luis Alcoriza Conductor: Thomas Ade`s Director: Tom Cairns Set and Costume Design: Hildegard Bechtler Lighting Design: Jon Clark Projection Design: Tal Yarden Choreography: Amir Hosseinpour Video Director: Gary Halvorson Edmundo de Nobile: Joseph Kaiser Lucıa de Nobile: Amanda Echalaz Leticia Maynar: Audrey Luna Leonora Palma: Alice Coote Silvia de Avila: Sally Matthews Francisco de Avila: Iestyn Davies Blanca Delgado: Christine Rice Alberto Roc: Rod Gilfry Beatriz: Sophie Bevan Eduardo: David Portillo Raul Yebenes: Frederic Antoun Colonel Alvaro Gomez: David Adam Moore Sen~or Russell: Kevin Burdette Dr. Carlos Conde: Sir John Tomlinson The Opera Quarterly Vol. 34, No. 4, pp. 355–372; doi: 10.1093/oq/kbz001 Advance Access publication April 16, 2019 # The Author(s) 2019. Published by Oxford University Press. All rights reserved. For permissions, please email: [email protected] 356 | morris et al Editorial Introduction The pages of The Opera Quarterly have featured individual and panel reviews of op- era in performance both in its traditional theatrical domain and on video, including Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/oq/article/34/4/355/5469296 by University of California, Irvine user on 18 March 2021 reports from individual critics and from panels assembled to review a single produc- tion or series of productions on DVD. -

Buffy's Glory, Angel's Jasmine, Blood Magic, and Name Magic

Please do not remove this page Giving Evil a Name: Buffy's Glory, Angel's Jasmine, Blood Magic, and Name Magic Croft, Janet Brennan https://scholarship.libraries.rutgers.edu/discovery/delivery/01RUT_INST:ResearchRepository/12643454990004646?l#13643522530004646 Croft, J. B. (2015). Giving Evil a Name: Buffy’s Glory, Angel’s Jasmine, Blood Magic, and Name Magic. Slayage: The Journal of the Joss Whedon Studies Association, 12(2). https://doi.org/10.7282/T3FF3V1J This work is protected by copyright. You are free to use this resource, with proper attribution, for research and educational purposes. Other uses, such as reproduction or publication, may require the permission of the copyright holder. Downloaded On 2021/10/02 09:39:58 -0400 Janet Brennan Croft1 Giving Evil a Name: Buffy’s Glory, Angel’s Jasmine, Blood Magic, and Name Magic “It’s about power. Who’s got it. Who knows how to use it.” (“Lessons” 7.1) “I would suggest, then, that the monsters are not an inexplicable blunder of taste; they are essential, fundamentally allied to the underlying ideas of the poem …” (J.R.R. Tolkien, “Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics”) Introduction: Names and Blood in the Buffyverse [1] In Joss Whedon’s Buffy the Vampire Slayer (1997-2003) and Angel (1999- 2004), words are not something to be taken lightly. A word read out of place can set a book on fire (“Superstar” 4.17) or send a person to a hell dimension (“Belonging” A2.19); a poorly performed spell can turn mortal enemies into soppy lovebirds (“Something Blue” 4.9); a word in a prophecy might mean “to live” or “to die” or both (“To Shanshu in L.A.” A1.22). -

Dulce Maria Loynaz: a Woman Who No Longer Exists

Dulce Maria Loynaz: A Woman Who No Longer Exists http://quod.lib.umich.edu/cgi/t/text/text-idx?cc=mqr;c=mqr;c=mqrarchiv... Behar, Ruth Volume XXXVI, Issue 4, Fall 1997 Permalink: http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.act2080.0036.401 [http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.act2080.0036.401] [http://quod.lib.umich.edu/m/mqrimage/x-97401-und-01/1?subview=detail;view=entry] DULCE MARIA LOYNAZ WITH CUBAN WRITER PABLO ARMANDO FERNANDEZ AND RUTH BEHAR, 1995 In 1993, when I first came to know Dulce María Loynaz, she had already turned ninety. She was frail, almost blind, hard of hearing, and tired easily. But she was still lucid, wry, concise and sharp in her answers to questions, and listened attentively if you sat very close and read poetry to her. She had the kindness to receive me, several times, at her home, a mansion of ravaged elegance on 19 and E Street in the Vedado section of Havana, whose fenced courtyard is famous for its massive stone statue of a headless woman. Our meeting time, arranged in advance with her niece, who acted as Dulce María's manager, was always at five in the afternoon, the sacred hour at which a Spanish bullfighter met his death in the poem immortalized by Federico García Lorca. [1] [http://quod.lib.umich.edu/m/mqr/act2080.0036.401/--dulce-maria-loynaz-a-woman-who-no-longer-exists?c=mqr;c=mqrarchive;g=mqrg;id=N1;note=ptr;rgn=main;view=trgt;xc=1] All guests, I learned later, were told to come at five in the afternoon. -

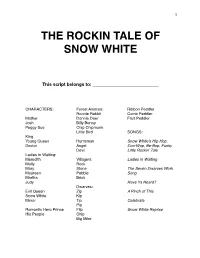

Rockin Snow White Script

!1 THE ROCKIN TALE OF SNOW WHITE This script belongs to: __________________________ CHARACTERS: Forest Animals: Ribbon Peddler Roonie Rabbit Comb Peddler Mother Donnie Deer Fruit Peddler Josh Billy Bunny Peggy Sue Chip Chipmunk Little Bird SONGS: King Young Queen Huntsman Snow White’s Hip-Hop, Doctor Angel Doo-Wop, Be-Bop, Funky Devil Little Rockin’ Tale Ladies in Waiting: Meredith Villagers: Ladies in Waiting Molly Rock Mary Stone The Seven Dwarves Work Maureen Pebble Song Martha Brick Judy Have Ya Heard? Dwarves: Evil Queen Zip A Pinch of This Snow White Kip Mirror Tip Celebrate Pip Romantic Hero Prince Flip Snow White Reprise His People Chip Big Mike !2 SONG: SNOW WHITE HIP-HOP, DOO WOP, BE-BOP, FUNKY LITTLE ROCKIN’ TALE ALL: Once upon a time in a legendary kingdom, Lived a royal princess, fairest in the land. She would meet a prince. They’d fall in love and then some. Such a noble story told for your delight. ’Tis a little rockin’ tale of pure Snow White! They start rockin’ We got a tale, a magical, marvelous, song-filled serenade. We got a tale, a fun-packed escapade. Yes, we’re gonna wail, singin’ and a-shoutin’ and a-dancin’ till my feet both fail! Yes, it’s Snow White’s hip-hop, doo-wop, be-bop, funky little rockin’ tale! GIRLS: We got a prince, a muscle-bound, handsome, buff and studly macho guy! GUYS: We got a girl, a sugar and spice and-a everything nice, little cutie pie. ALL: We got a queen, an evil-eyed, funkified, lean and mean, total wicked machine. -

Quaking Bankers

the grand jury nor the fact that any [claimed by the plaintiffs to lie acbool a indictment for felony has been found and Indemnity lands arc in n dity TIS BANKERS against MARRIED BADGER DAY CHINESE MUST GO QUAKING any person not in custody .>r DR. SHAW IS swamp contention ot under recognizance; you are to present lands The main no man for envy, hatred or malice; th* plaintltfs attorneys will lie that tin neither an you to leave any man u.i- no to -el ii MILWAUKEE GRAND JURY l I' NOB THE legislature has power aside 'VI \IR o\ To ix;i; ivoss has a mind ok his allK presented for love, fear, favor, MISS BESSIE LA'‘ON *RI.I is I I I RNKD ER ■ affection sclhk'l lauds from sale. The order will or hope of reward. But it becomes GOES TO WORK. " ISO INSIN PFOPI i: OWN. your duty to investigate carefully and EDITORS BRIDE. Is* made when the attorneys agree impartially the matters given you in as to what circuit court shall try the charge things and to present truly as ease, the attorney general preferring they may have come to your know! ( AI.iIOUNIAN MAM'S AN JUDGE WAIJ.BKR DELIVERS A THE CEREMONY TAKES PLACE AT the Dane county -court, while the GREAT TIItt'VDS Wild THRONG no. IM edge, according to the best of your mi- llerstun ding.” plaint tfs attorneys. Messrs Hilton SWEEPING CHARGE. READING. F V THE EXPOSITION GROUNDS. KttKTANT 111 UNO Disrtr. ’ Attorney says llaminel that and 1 ullar, wish to take it to Wan all Milwaukee attorneys of any stand- ing are comnvtod w;h bank cases and kesha ounty. -

NONINO Prize the Jury Presided by the Nobel Laureate Naipaul Has

NONINO Prize The jury presided by the Nobel Laureate Naipaul has chosen two intellectuals that support religious tolerance and free thinking. By FABIANA DALLA VALLE The Albanian poet Ismail Kadare, the philosopher Giorgio Agamben and the P(our) project are respectively the winners of the International Nonino Prize, the “Master of our time” and the “Nonino Risit d’Aur – Gold vine shoot” of the forty-third edition of the Nonino, born in 1975 to give value to the rural civilization. The jury presided by V.S. Naipaul, Nobel Laureate in Literature 2001, and composed by Adonis, John Banville, Ulderico Bernardi, Peter Brook, Luca Cendali, Antonio R. Damasio, Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie, James Lovelock, Claudio Magris, Norman Manea, Edgar Morin and Ermanno Olmi, has awarded the prestigious acknowledgements of the 2018 edition. Ismail Kadare, poet, novelist, essay writer and script writer born in Albania (he left his country as a protest against the communist regime which did not take any steps to allow the democratization of the country ndr.), for the prestigious jury of the Nonino is a «Bard fond and critical of his country, between historical realities and legends, which evoke grandeur and tragedies of the Balkan and Ottoman past and has created great narrations. An exile in Paris for more than twenty years “not to offer his services to tyranny”, he has refused the silence which is the evil’s half, often immersing his narration in imaginary worlds, becoming the witness of the horrors committed by totalitarianism and its inquisitors. He has made religious tolerance one of the foundations of his work». -

Slayage, Number 16

Roz Kaveney A Sense of the Ending: Schrödinger's Angel This essay will be included in Stacey Abbott's Reading Angel: The TV Spinoff with a Soul, to be published by I. B. Tauris and appears here with the permission of the author, the editor, and the publisher. Go here to order the book from Amazon. (1) Joss Whedon has often stated that each year of Buffy the Vampire Slayer was planned to end in such a way that, were the show not renewed, the finale would act as an apt summation of the series so far. This was obviously truer of some years than others – generally speaking, the odd-numbered years were far more clearly possible endings than the even ones, offering definitive closure of a phase in Buffy’s career rather than a slingshot into another phase. Both Season Five and Season Seven were particularly planned as artistically satisfying conclusions, albeit with very different messages – Season Five arguing that Buffy’s situation can only be relieved by her heroic death, Season Seven allowing her to share, and thus entirely alleviate, slayerhood. Being the Chosen One is a fatal burden; being one of the Chosen Several Thousand is something a young woman might live with. (2) It has never been the case that endings in Angel were so clear-cut and each year culminated in a slingshot ending, an attention-grabber that kept viewers interested by allowing them to speculate on where things were going. Season One ended with the revelation that Angel might, at some stage, expect redemption and rehumanization – the Shanshu of the souled vampire – as the reward for his labours, and with the resurrection of his vampiric sire and lover, Darla, by the law firm of Wolfram & Hart and its demonic masters (‘To Shanshu in LA’, 1022). -

Mini Cocktails

WELCOME TO SCROLL DOWN TO EXPLORE OUR MENU APERITIVO FROM 3PM MIXED OLIVES, Orange Zest ............................ 6 ORTIZ ANCHOVIES ......................................21 Toasted Bread, Butter, Guindilla Peppers POLLASTRINI SARDINES ............................15 Chilli, Misura Crackers, Lemon SALUMI MISTI ............................................. 35 L.P.’s Mortadella & Salami, Prosciutto di Parma, Pickles THREE CHEESES ........................................ 35 Rotating selection of Cheese; Crackers, Local Honey MINI COCKTAILS $13 HAPPY HOUR FROM 4-5PM $7 MARTINI AUSTRALIANO Widges Gin, Lemon Myrtle, Apera Fino COFFEE NEGRONI Widges Gin, Mr Black Amaro, Campari, Vermouth Rosso ESPRESSO MARTINI Plantation 3yo Rum, Mr Black, Coconut Water, Espresso PERAMERICANO Saint Felix Bitter Citrus Aperitivo, Vermouth Rosso, Strangelove Pear Soda IRISH COFFEE Roe & Co Irish Whiskey, Honey, Muscovado, Filter Coffee, Almonds, Cream *vegan option available **contains nuts BREAKFAST MANHATTAN Bulleit Rye Whiskey, Banana Skin, Granola, Almond, Vermouth Bianco x SAMMY JUNIOR WILD MARTINEZ Saint Felix Wild Forest Gin, Vermouth Rosso, Maraschino, Orange bitters 16 AUTUMN SAZERAC Saint Felix Cherry & Cacao Husk Brandy, Genepi, Cascara, Peychauds bitters 16 FELIX COLLINS Saint Felix Yuzu & Green Tea Spirit, Jasmine Tea, Citrus, Yuzu Soda 16 APERITIVO COCKTAILS CAMPARI SODA..............10 ‘Il Soldatino’ GARIBALDINI......................9 Saint Felix Bitter Citrus Aperitivo whizzed with Fresh Orange GIN & TONIC.........................9 Widges Gin, -

My Habana—The Chronicle Review—The Chronicle of Higher Education

My Habana—The Chronicle Review—The Chronicle of Higher Education September 7, 2009 My Habana By Ruth Behar Say the word Havana—or call her by her given name, La Habana—and you can't help but conjure up an image of a gorgeous city ravished by the sea and by history. La Habana channels the spirit of Aphrodite, of Venus, of Ochún, the Afro-Cuban goddess of the Santeria religion, who represents beauty, sensuality, amor. So how can I not feel blessed? I was conceived while my parents honeymooned in Robert Caplin the beach town of Varadero, but I had the good fortune to be born in the only city on earth where I would have wanted to be born— Havana. Gracias, Mami y Papi! I've been able to return many times, my credentials as a cultural anthropologist serving as my passport, allowing me to create a parallel life in the home I was torn away from when I was just 4. My parents won't go back, but since 1991, I've been determined to reclaim my native city. I can't remember anything of my life there, but maybe this amnesia is a blessing. I go back with innocent eyes, gazing at La Habana with unabashed wonder. Mami and Papi grew up in the hustle and bustle of La Habana Vieja, the old colonial part of the city. They lived next door to Afro-Cuban neighbors, amid Jewish shmatte shops and Galician grocers, near the city's Chinatown. After I was born, they moved to El Vedado, a modern neighborhood lined with banyan trees. -

So.Re.Com.THE.NET.@-NEWS N°16

http://www.europhd.eu http://www.europhd.eu/SoReComTHEmaticNETwork !"#$%#&"'#()*#+*(#,-.+*/!,!"#!$%!&!'()*+,*-!./$/, (0%,123%4563%7,+%89:%;%5,"<,30%,*=5">%62,?0@,"2,!"A16:,$%>5%9%236B"29,627,&"''=21A6B"2,,, 627,"<,30%,,!"#$%#&"'#,()*'6BA,+*(8"5C, 2010 Nonino “Master of his Time” Prize awarded to Serge Moscovici The 2010 Nonino “Master of his time” prize was awarded to Serge Moscovici, Romanian- born social psychologist. The decision came from a jury chaired by V.S. Naipaul, Nobel Prize for Literature in 2001, and composed by Adonis, Peter Brook, John Banville, Ulrich Bernardi, Luca Cendali, Antonio R. Damasio, Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie, James Lovelock, Claudio Magris, Norman Manea, Morando Morandini, Edgar Morin and Ermanno Olmi. The awards ceremony took place at the Distilleries in Ronchi di Nonino Percoto (Udine) Saturday, January 30, 2010. Moscovici was born in Romania, frequently relocating, together with his father, spending time in Cahul, Gala!i, and Bucharest. He formed himself at the school of life, first in a forced labor camp and then as an emigrant. He moved to France after 1947 and studied psychology at the Sorbonne, while being employed by an industrial enterprise. He is director emeritus of studies at the Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales and founder and director of the Laboratoire Européen de Psychologie Sociale at the Maison des Sciences de l’Homme. He is a member of the European Academy of Sciences and Arts and Officer of the Légion d’honneur, as well as a member of the Russian Academy of Sciences and honorary member of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences. Moscovici’s work in the field of social psychology is acknowledged all over the world, above all for the Social Representations theory and the influence theory regarding the minorities and their relationship with dominant societies. -

Beer & Coolers Cocktails

BEER & COOLERS COCKTAILS all cocktails 2~3oz Draught Spritz & Sippers Classics GREAT LAKES BREWERY - SEASONAL IPA / toronto /MP HUGO SPRITZ NEGRONI CLASSICO elderflower + lemon + prosecco + basil /12 gin + italian sweet vermouth + campari /14 PERONI EUROPEAN PALE LAGER / 5.1% / italy /7½ STEAM WHISTLE PILSNER / 5% / toronto /7¼ APEROL SPRITZ PAPER PLANE aperol + orange bitters + prosecco + soda /12 wild turkey bourbon + aperol + amaro nonino + lemon /13 AFFINO SPRITZ affino aperitivo + lemon + prosecco /12 AMERICANO Bottles + Cans italian sweet vermouth + campari + soda /12 OLD FASHIONED PERONI PALE LAGER / italy / 5.1% / 330ml btl /7¼ wild turkey bourbon + sugar + bitters /14 CORONA / mexico / 4.6% / 330mL btl /7¼ BELLWOODS / JELLY KING / SOUR / toronto / 5.6% / 500mL btl /14 STEAM WHISTLE PREMIUM PILSNER / toronto / 5% / 473mL can /7¾ Cocktails WOODHOUSE IPA / toronto / 6% / 473mL can /7¾ DARK ‘N’ STORMY WOODHOUSE CHERRY KOLSCH / toronto / 5.2% / 473mL can /7¾ gosling’s dark rum + lime juice + ginger beer + SPEARHEAD HAWAIIAN PALE ALE / kingston / 6% / 473mL can /7½ orange bitters /13 BUDWEISER ZERO / toronto / 0% / 473mL can /6½ LA PALOMA tromba silver + grapefruit soda + lime juice + salt /13 FIZZY LIZZY beefeater gin + casis + simple syrup + lemon + Ciders & Coolers soda /14 CAFÉ SHAKERATO SPY CIDER HOUSE / ‘GOLDEN EYE’ / DRY CIDER / collingwood / 5% / 473mL can /8¼ shaken espresso + sugar + coffee & nut liqueur + WHITE CLAW HARD SELTZER, RASPBERRY / toronto / 5% / 473mL can /7½ grappa + chocolate /13 WHITE CLAW HARD SELTZER, WATERMELON / toronto / 5% / 473mL can /7½ RED GLASS WHITE GLASS 5 or 8oz 5 or 8oz CABERNET SAUVIGNON 2019 PRIMITIVO 2019 PINOT GRIGIO 2018 ROSÉ 2019 sterling, california u.s.a.