Mission Santa Cruz De San Sabá Case Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Spanish Return to Texas Main Ideas Key Terms and People 1

DO NOT EDIT--Changes must be made through “File info” CorrectionKey=TX-A Section 3 The Spanish Return to Texas Main Ideas Key Terms and People 1. In response to a perceived threat from the French, the • Francisco Hidalgo Spanish resettled in East Texas in the early 1700s. • Louis Juchereau de 2. The Spanish built several missions, a presidio, and the St. Denis region's first civil settlement near what is now San Antonio. • Domingo Ramón • Antonio Margil de Jesús Why It Matters Today • Martín de Alarcón The Spanish tried to protect their hold on Texas by • El Camino Real barring foreign trade in the region. Use current events sources to learn more about free trade issues or a trade dispute between nations today. TEKS: 1B, 2C, 9A, 21A, 21B, 21C, 22D The Story Continues Father Francisco Hidalgo was a patient but persistent myNotebook man. Since becoming a Franciscan at the age of 15, he Use the annotation had longed to become a missionary, travel, and spread the Bleed Art Guide: tools in your eBook All bleeding art should be extended fullyto to takethe notes on the Catholic faith. After arriving in New Spain, the young priest bleed guide. return of Spanish missionaries and heard many stories about Texas. He became determined to settlers to Texas. go there to teach Texas Indians about Catholicism. Delay after delay prevented Father Hidalgo from reaching them. But he knew that his chance would come. Art and Non-Teaching Text Guide: Folios, annos, standards, non-bleeding art, etc. should Back to East Texas never go beyond this guide on any side, 1p6 to trim. -

Changes in Spanish Texas

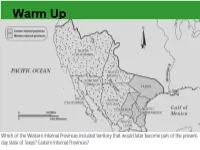

Warm Up The Mexican National Era Unit 5 Vocab •Immigrant - a person who comes to a country where they were not born in order to settle there •Petition - a formal message requesting something that is submitted to an authority •Tejano - a person of Mexican descent living in Texas •Militia - civilians trained as soldiers but not part of the regular army •Empresario -the Spanish word for a land agent whose job it was to bring in new settlers to an area •Anglo-American - people whose ancestors moved from one of many European countries to the United States and who now share a common culture and language •Recruit - to persuade someone to join a group •Filibuster - an adventurer who engages in private rebellious activity in a foreign country •Compromise - an agreement in which both sides give something up •Republic - a political system in which the supreme power lies in a body of citizens who can elect people to represent them •Neutral - Not belonging to one side or the other •Cede - to surrender by treaty or agreement •Land Title - legal document proving land ownership •Emigrate - leave one's country of residence for a new one Warm Up Warm-up • Why do you think that the Spanish colonists wanted to break away from Spain? 5 Unrest and Revolution Mexican Independence & Impact on Texas • Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla – Gave a speech called “Grito de Dolores” in 1810. Became known as the Father of the Mexican independence movement. • Leads rebellion but is killed in 1811. • Mexico does not win independence until 1821. Hidalgo’s Supporters Rebel Against Spain • A group of rebels led by Juan Bautista de las Casas overthrew the Spanish government in San Antonio. -

Spain's Texas Patriots ~ Its 1779-1,783 War with England During the American Revolution

P SPAIN'S TEXAS PATRIOTS ~ ITS 1779-1,783 WAR WITH ENGLAND DURING THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION PART 5 OF SPANISH BORDERLANDS STUDIES by Granville W. and N. C. Hough P ! i ! © Copyright 2000 1 by Granville W. and N. C. Hough 3438 Bahia Blanea West, Apt B Lagtma Hills, CA 92653-2830 Email: [email protected] Other books in this series include: Spain's California Patriots in its 1779-1783 War with England - During the American Revolution, Part 1, 1998. Spain's California Patriots in its 1779-1783 War with England - During the American Revolution, Part 2, 1999. Spain's Arizona Patriots in its 1779-1783 War with England - During the Amencan Revolution, Third Study of the Spanish Borderlands, 1999. Spain's New Mexico Patriots in its 1779-1783 War with England - During the.American Revolution, Fourth Study of the Spanish Borderlands, 1999. Published by: SHHAR PRESS Society of Hispanic Historical and Ancestral Research , P.O. Box 490 Midway City, CA 92655°0490 (714) 894-8161 Email: SHHARP~s~aol.com ;.'."/!';h',-:/.t!j.:'."-i ;., : [::.'4"!".': PREFACE o In 1996, the authors became aware that neither the NSDAR (National Society for the Daughters of the American Revolution) nor the NSSAR (National Society for the Sons of the American Revolution) would accept descendants of Spanish citi~e,qs of California who had contributed funds to defray expenses of the 1779-1783 war with England. As the patriots being turned down as suitable ancestors were also soldiers, the obvious question became: "Why base your membership application on a monetary contribution when the ancestor soldier had put.his life at stake?" This led to a study of how the Spani~a Army and Navy ~ad worked during the war to defeat the :~'. -

Spanish Relations with the Apache Nations East of the Rio Grande

SPANISH RELATIONS WITH THE APACHE NATIONS EAST OF THE RIO GRANDE Jeffrey D. Carlisle, B.S., M.A. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2001 APPROVED: Donald Chipman, Major Professor William Kamman, Committee Member Richard Lowe, Committee Member Marilyn Morris, Committee Member F. Todd Smith, Committee Member Andy Schoolmaster, Committee Member Richard Golden, Chair of the Department of History C. Neal Tate, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Carlisle, Jeffrey D., Spanish Relations with the Apache Nations East of the Río Grande. Doctor of Philosophy (History), May 2001, 391 pp., bibliography, 206 titles. This dissertation is a study of the Eastern Apache nations and their struggle to survive with their culture intact against numerous enemies intent on destroying them. It is a synthesis of published secondary and primary materials, supported with archival materials, primarily from the Béxar Archives. The Apaches living on the plains have suffered from a lack of a good comprehensive study, even though they played an important role in hindering Spanish expansion in the American Southwest. When the Spanish first encountered the Apaches they were living peacefully on the plains, although they occasionally raided nearby tribes. When the Spanish began settling in the Southwest they changed the dynamics of the region by introducing horses. The Apaches quickly adopted the animals into their culture and used them to dominate their neighbors. Apache power declined in the eighteenth century when their Caddoan enemies acquired guns from the French, and the powerful Comanches gained access to horses and began invading northern Apache territory. -

Hispanic Texans

texas historical commission Hispanic texans Journey from e mpire to Democracy a GuiDe for h eritaGe travelers Hispanic, spanisH, spanisH american, mexican, mexican american, mexicano, Latino, Chicano, tejano— all have been valid terms for Texans who traced their roots to the Iberian Peninsula or Mexico. In the last 50 years, cultural identity has become even more complicated. The arrival of Cubans in the early 1960s, Puerto Ricans in the 1970s, and Central Americans in the 1980s has made for increasing diversity of the state’s Hispanic, or Latino, population. However, the Mexican branch of the Hispanic family, combining Native, European, and African elements, has left the deepest imprint on the Lone Star State. The state’s name—pronounced Tay-hahs in Spanish— derives from the old Spanish spelling of a Caddo word for friend. Since the state was named Tejas by the Spaniards, it’s not surprising that many of its most important geographic features and locations also have Spanish names. Major Texas waterways from the Sabine River to the Rio Grande were named, or renamed, by Spanish explorers and Franciscan missionaries. Although the story of Texas stretches back millennia into prehistory, its history begins with the arrival of Spanish in the last 50 years, conquistadors in the early 16th cultural identity century. Cabeza de Vaca and his has become even companions in the 1520s and more complicated. 1530s were followed by the expeditions of Coronado and De Soto in the early 1540s. In 1598, Juan de Oñate, on his way to conquer the Pueblo Indians of New Mexico, crossed the Rio Grande in the El Paso area. -

Bulletin 2 (8/86)

Dorothy Sloan Books – Bulletin 2 (8/86) 1. ABBOT, G. H. Mexico, and the United States; Their Mutual Relations and Common Interests. New York: Putnam, 1869. xvi, 391 pp., large folding colored map of Mexico, Texas, and the borderlands by Colton, another double-page map, steel-engraved portraits of Juárez and Romero. 8vo, original plum cloth, gilt seal of Mexican eagle on front cover. Slight discoloration to binding, else fine, map excellent. First edition. Larned 3925: “A useful guide to the constitutional history, especially for the period from 1824 to 1859.” Palau 521. $125.00 2. ADAMS, Ramon F. Come an’ Get It. The Story of the Old Cowboy Cook. Norman: Univ. Okla. Press [1952]. xii, 170 [1] pp., illustrations by Nick Eggenhofer. 8vo, original terracotta cloth, brown backstrip. Very fine in d.j. First edition. Adams, Herd 12: “The first and only book devoted to this unique and interesting character.” $35.00 3. ALAMAN, Lucas. Iniciativa de ley proponiendo al gobierno las medidas que se debian tomar para la seguridad del estado de Tejas y conservar la integridad del territorio mexicano de cuyo proyecto emanó la ley de 6 abril de 1830. Mexico: Vargas Rea, 1946. 50 pp. 8vo, original white printed wrappers. Very fine. First edition, limited edition (#16 of 100 copies). Alaman’s argument for one of the fundamental Texas laws, the Law of April 6, 1830, which banned U.S. immigration into Texas and, according to traditional Anglo interpretation, led to the Texas Revolution. See Streeter 759. $65.00 4. ALVARADO TEZOZOMOC, Hernando & Juan de Tovar. -

The Spanish Legacy in North America and the Historical Imagination Author(S): David J

The Spanish Legacy in North America and the Historical Imagination Author(s): David J. Weber Source: The Western Historical Quarterly, Vol. 23, No. 1, (Feb., 1992), pp. 5-24 Published by: Western Historical Quarterly, Utah State University on behalf of the The Western History Association Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/970249 Accessed: 02/06/2008 14:18 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=whq. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We enable the scholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform that promotes the discovery and use of these resources. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org DavidJ. Weber Twenty-ninth President of the Western History Association TheSpanish Legacy in NorthAmerica and the HistoricalImagination1 DAVIDJ.WEBER The past is a foreign country whose features are shaped by today's predilections, its strangeness domesticated by our own preservation of its vestiges. -

Life in Spanish Texas Main Ideas Key Terms 1

DO NOT EDIT--Changes must be made through “File info” CorrectionKey=TX-A Section 5 Life in Spanish Texas Main Ideas Key Terms 1. Mission life was structured around prayer and work. • ayuntamiento 2. The life of a presidio soldier could be harsh. • alcalde 3. Life in Spanish settlements reflected the influence of • vaqueros Spanish culture, which is still felt in Texas today. Why It Matters Today Many states in the American Southwest still show signs of a strong Spanish influence. Use current events sources to identify one way this influence is felt in your area of Texas today. TEKS: 2C, 2F, 10A, 19C, 19D, 21B, 21C, 22D The Story Continues The mission bells rang as daylight began to brighten the dark myNotebook Texas sky. Rising from buffalo-skin mattresses, American Use the annotation Indians walked to the chapel. The priests counted the tools in your eBook to take notes on life churchgoers as they entered. Then the congregation chanted Bleed Art Guide: in Spanish Texas. and prayed. Later, the Spaniards and the Indians rose to sing All bleeding art should be extended fully to the bleed guide. a song called El Alabado. It told the churchgoers to lift their hearts and praise God. It was the start of another day at a Spanish mission in Texas. Life in the Missions The Spanish wanted Texas Indians to live in the missions and learn the Art and Non-Teaching Text Guide: Folios, annos, standards, non-bleeding art, etc. should Spanish way of life. In the missions, life followed a regular pattern of never go beyond this guide on any side, 1p6 to trim. -

Western Americana

CATALOGUE TWO HUNDRED NINETY-NINE Western Americana WILLIAM REESE COMPANY 409 Temple Street New Haven, CT 06511 (203) 789-8081 A Note This catalogue contains much in the way of new acquisitions in Western Americana, along with several items from our stock that have not been featured in recent catalogues. Printed, manuscript, cartographic, and visual materials are all represented. A theme of the catalogue is the exploration, settlement, and development of the trans-Mississippi West, and the time frame ranges from the 16th century to the early 20th. Highlights include copies of the second and third editions of The Book of Mormon; a certificate of admission to Stephen F. Austin’s Texas colony; a document signed by the Marquis de Lafayette giving James Madison power of attorney over his lands in the Louisiana Territory; an original drawing of Bent’s Fort; and a substantial run of the wonderfully illustrated San Francisco magazine, The Wasp, edited by Ambrose Bierce. Speaking of periodicals, we are pleased to offer the lengthiest run of the first California newspaper to appear on the market since the Streeter Sale, as well as a nearly complete run of The Dakota Friend, printed in the native language. There are also several important, early California broadsides documenting the political turmoil of the 1830s and the seizure of control by the United States in the late 1840s. From early imprints to original artwork, from the fur trade to modern construction projects, a wide variety of subjects are included. Available on request or via our website are our recent catalogues 291 The United States Navy; 292 96 American Manuscripts; 294 A Tribute to Wright Howes: Part I; 295 A Tribute to Wright Howes: Part II; 296 Rare Latin Americana; 297 Recent Acquisitions in Ameri- cana, as well as Bulletins 25 American Broadsides; 26 American Views; 27 Images of Native Americans; 28 The Civil War; 29 Photographica, and many more topical lists. -

Unit 3: Exploration and Early Colonization (Part 2)

Unit 3: Exploration and Early Colonization (Part 2) Spanish Colonial Era 1700-1821 For these notes – you write the slides with the red titles!!! Goals of the Spanish Mission System To control the borderlands Mission System Goal Goal Goal Represent Convert American Protect Borders Spanish govern- Indians there to ment there Catholicism Four types of Spanish settlements missions, presidios, towns, ranchos Spanish Settlement Four Major Types of Spanish Settlement: 1. Missions – Religious communities 2. Presidios – Military bases 3. Towns – Small villages with farmers and merchants 4. Ranchos - Ranches Mission System • Missions - Spain’s primary method of colonizing, were expected to be self-supporting. • The first missions were established in the El Paso area, then East Texas and finally in the San Antonio area. • Missions were used to convert the American Indians to the Catholic faith and make loyal subjects to Spain. Missions Missions Mission System • Presidios - To protect the missions, presidios were established. • A presidio is a military base. Soldiers in these bases were generally responsible for protecting several missions. Mission System • Towns – towns and settlements were built near the missions and colonists were brought in for colonies to grow and survive. • The first group of colonists to establish a community was the Canary Islanders in San Antonio (1730). Mission System • Ranches – ranching was more conducive to where missions and settlements were thriving (San Antonio). • Cattle were easier to raise and protect as compared to farming. Pueblo Revolt • In the late 1600’s, the Spanish began building missions just south of the Rio Grande. • They also built missions among the Pueblo Indians of New Mexico. -

Former Chief Justice Jack Pope, 100 Years Old, Signed Copies of His Book Common Law Judge: Selected Writings Fof Chief Justice Jack Pope of Texas

Journal of the TEXAS SUPREME COURT HISTORICAL SOCIETY Winter 2013 Vol. 3, No. 2 General Editor Lynne Liberato Executive Editor David Furlow Columns A Brief History of the Society Takes Over Maintenance of the Journal of the Texas Supreme Court Supreme Court’s Alumni Directory President’s Page The Society has offered to assume By Douglas W. Alexander Historical Society maintenance of the Court’s directory I celebrate those who By Lynne Liberato in order to alleviate the administrative helped make former When I became the burden its upkeep imposes on Court staff. Chief Justice Jack Pope’s Society’s president, I Read more... knew that producing a new book a reality. Douglas W. Read more... Alexander newsletter was critical to our development as an organization. Supreme Court History Book Ends Its Fellows Column Read more... Lynne Liberato First Year with a Holiday Sales Push By David J. Beck The Society is running a The Fellows are excited series of ads to reach the to be working on their Journal Indexes larger audience of Texas second reenactment of a These indexes of past Journal issues, attorneys who might not historic case. arranged by issue and by author, are a know about the book or Read more... David J. Beck great resource for finding articles. the Society. Read more... Read more... James Haley’s book Features Significant Dates in the Society’s TSHA Joint Session Goes to the 170 Years of Texas Contract Law—Part 2 History of the Supreme Court Dark Side of Court History By Richard R. Orsinger of the Republic of Texas The theme of the upcoming Society- Texas took its pleading sponsored session at the TSHA Annual December was an important month Meeting is guaranteed to generate more practices from Spanish in the history of the Republic of Texas law, where the emphasis than passing interest in the Supreme Supreme Court. -

Texas History Ch

Texas History Ch. 5-6 1519: De Pineda maps the Gulf of Mexico coastline and sees Texas coast for first time 1528: Cabeza de Vaca is shipwrecked on Texas coast and meets Karankawas Cabeza de Vaca and his companions found Texas to be harsh. He wrote 1st European account of life in North America. Cortes led the conquest of the Aztec Empire. Indians told Spanish tales of cities of gold in the region Spanish were able to defeat large groups of Indians with superior armor, weapons, horses, and killing them by spreading European diseases Diseases killed the Indians but did not kill the Europeans because Indians had not been previously exposed to those diseases. Besides disease, food and animals were part of the Columbian Exchange. Conquistadores wanted to find Gold, spread Catholic religion, and obtain Glory and land. They did NOT want to befriend the American Indians Coronado looked for gold at Cibola and Quivira When Fray Marcos and Estevanico reached what they thought was a golden city, Estevanico was killed by the Indians. Antonio Margil de Jesus was a Franciscan who founded missions in Texas. Alonso de Leon and Damian Massanet established San Francisco de los Tejas. Daily life in a mission included working and praying. Native Americans had to stay inside the mission walls. Native Americans often contracted diseases from Europeans inside the mission. Tejas Indians turned against the Spanish after a disease outbreak killed many Indians. Both the Spanish and American Indians claimed the same land. Apaches became feared enemies of the Spanish after they obtained horses.