Kingdom of Cambodia Ministry of Health

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cambodia PRASAC Microfinance Institution

Maybank Money Express (MME) Agent - Cambodia PRASAC Microfinance Institution Branch Location Last Update: 02/02/2015 NO NAME OF AGENT REGION / PROVINCE ADDRESS CONTACT NUMBER OPERATING HOUR 1 PSC Head Office PHNOM PENH #25, Str 294&57, Boeung Kengkang1,Chamkarmon, Phnom Penh, Cambodia 023 220 102/213 642 7.30am-4pm National Road No.5, Group No.5, Phum Ou Ambel, Krong Serey Sophorn, Banteay 2 PSC BANTEAY MEANCHEY BANTEAY MEANCHEY Meanchey Province 054 6966 668 7.30am-4pm 3 PSC POAY PET BANTEAY MEANCHEY Phum Kilometre lek 4, Sangkat Poipet, Krong Poipet, Banteay Meanchey 054 63 00 089 7.30am-4pm Chop, Chop Vari, Preah Net 4 PSC PREAH NETR PREAH BANTEAY MEANCHEY Preah, Banteay Meanchey 054 65 35 168 7.30am-4pm Kumru, Kumru, Thmor Puok, 5 PSC THMAR POURK BANTEAY MEANCHEY Banteay Meanchey 054 63 00 090 7.30am-4pm No.155, National Road No.5, Phum Ou Khcheay, Sangkat Praek Preah Sdach, Krong 6 PSC BATTAMBANG BATTAMBANG Battambang, Battambang Province 053 6985 985 7.30am-4pm Kansai Banteay village, Maung commune, Moung Russei district, Battambang 7 PSC MOUNG RUESSEI BATTAMBANG province 053 6669 669 7.30am-4pm 8 PSC BAVEL BATTAMBANG Spean Kandoal, Bavel, Bavel, BB 053 6364 087 7.30am-4pm Phnom Touch, Pech Chenda, 9 PSC PHNOM PROEK BATTAMBANG Phnum Proek, BB 053 666 88 44 7.30am-4pm Boeng Chaeng, Snoeng, Banan, 10 PSC BANANN BATTAMBANG Battambang 053 666 88 33 7.30am-4pm No.167, National Road No.7 Chas, Group No.10 , Phum Prampi, Sangkat Kampong 11 PSC KAMPONG CHAM KAMPONG CHAM Cham, Krong Kampong Cham, Kampong Cham Province 042 6333 000 7.30am-4pm -

Upper Secondary Education Sector Development Program: Construction of 73 Subprojects Initial Environmental Examination

Initial Environmental Examination (IEE) Project Number: 47136-003 Loan 3427-CAM (COL) July 2019 Kingdom of Cambodia: Upper Secondary Education Sector Development Program (Construction of 73 sub-projects: 14 new Secondary Resource Centers (SRCs) in 14 provinces, 5 Lower Secondary School (LSSs) upgrading to Upper Secondary School (USSs) in four provinces and 10 overcrowded USSs in six provinces) and 44 Teacher Housing Units or Teacher Quarters (TQs) in 21 provinces) This initial environmental assessment is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB’s Board of Directors, management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank AP -- Affected people CCCA -- Cambodia Climate Change Alliance CMAC -- Cambodian Mine Action Centre CMDG -- Cambodia Millennuum Development Goals CLO – Community Liaison Officer EA – Executing Agency EARF -- Environmental Assessment and Review Framework EHS -- Environmental and Health and Safety EHSO – Environmental and Health and Safety Officer EIA -- Environmental Impact Assessment EMIS – Education Management Information System EMP – Environmental Management Plan EO – Environment and Social Safeguard Officer ERC – Education Research -

World Bank Document

Royal Government of Cambodia Public Disclosure Authorized Asian Development Bank World Bank Inter-Ministerial Resettlement Committee Ministry of Economy and Finance Ministry of Industry Mines and Energy Loan No. 2052-CAM (SF) POWER DISTIRBUTION Public Disclosure Authorized AND GREATER MEKONG SUBREGION TRANSMISSION PROJECT Credit Number 3840-KH Rural Electrification and Transmission Project RESETTLEMENT ACTION PLAN Public Disclosure Authorized Final Version Public Disclosure Authorized January 2005 Inter-Ministerial Resettlement Committee Resettlement Resettlement Unit Action Plan Final Version January 2005 POWER DISTRIBUTION AND GREATER MEKONG SUBREGION TRANSMISSION PROJECT RESETTLEMENT ACTION PLAN FINAL VERSION January 2005 Inter-Ministerial Resettlement Committee Resettlement Resettlement Unit Action Plan Final Version January 2005 CONTENTS Abbreviations, Acronyms etc iv Definition of Terms vi Executive Summary vii 1 INTRODUCTION 1 2 SCOPE OF LAND ACQUISITION AND RESETTLEMENT 3 2.1 Project Description 3 2.1.1 Design Criteria COI Easements and WWP and TSS Substations 3 2.2 Proposed Transmission Line Route 6 2.2.1 Land Use 6 2.2.2 Administrative Areas 8 2.3 Route Selection 12 2.3.1 Engineering Survey - Use of GPS 12 2.3.2 Social Survey - Use of GPS for Field Work and Development of GIS Database 12 2.3.3 Route Selection 13 2.3.4 Connection Point in Phnom Penh 14 2.3.5 Northern Section: Phnom Penh to Takeo Town 14 2.3.6 Southern Section: Takeo Town to Vietnam Border 15 2.4 Project Impacts 16 2.4.1 Land Acquisition 16 2.4.2 Temporary Effects -

List of Interviewees

mCÄmNÐlÉkßrkm<úCa DOCUMENTATION CENTER OF CAMBODIA Phnom Penh, Cambodia LIST OF POTENTIAL INFORMANTS FROM MAPPING PROJECT 1995-2003 Banteay Meanchey: No. Name of informant Sex Age Address Year 1 Nut Vinh nut vij Male 61 Banteay Meanchey province, Mongkol Borei district 1997 2 Ol Vus Gul vus Male 40 Banteay Meanchey province, Mongkol Borei district 1997 3 Um Phorn G‘¿u Pn Male 50 Banteay Meanchey province, Mongkol Borei district 1997 4 Tol Phorn tul Pn ? 53 Banteay Meanchey province, Mongkol Borei district 1997 5 Khuon Say XYn say Male 58 Banteay Meanchey province, Mongkol Borei district 1997 6 Sroep Thlang Rswb føag Male 60 Banteay Meanchey province, Mongkol Borei district 1997 7 Kung Loeu Kg; elO Male ? Banteay Meanchey province, Phnom Srok district 1998 8 Chhum Ruom QuM rYm Male ? Banteay Meanchey province, Phnom Srok district 1998 9 Than fn Female ? Banteay Meanchey province, Phnom Srok district 1998 Documentation Center of Cambodia Searching for the Truth EsVgrkKrBit edIm, IK rcg©M nig yutþiFm‘’ DC-Cam 66 Preah Sihanouk Blvd. P.O.Box 1110 Phnom Penh Cambodia Tel: (855-23) 211-875 Fax: (855-23) 210-358 [email protected] www.dccam.org 10 Tann Minh tan; mij Male ? Banteay Meanchey province, Phnom Srok district 1998 11 Tatt Chhoeum tat; eQOm Male ? Banteay Meanchey province, Phnom Srok district 1998 12 Tum Soeun TMu esOn Male 45 Banteay Meanchey province, Preah Net Preah district 1997 13 Thlang Thong føag fug Male 49 Banteay Meanchey province, Preah Net Preah district 1997 14 San Mean san man Male 68 Banteay Meanchey province, -

United Nations A/HRC/21/35

United Nations A/HRC/21/35 General Assembly Distr.: General 20 September 2012 Original: English Human Rights Council Twenty-first session Agenda items 2 and 10 Annual report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights and reports of the Office of the High Commissioner and the Secretary-General Technical assistance and capacity-building The role and achievements of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights in assisting the Government and people of Cambodia in the promotion and protection of human rights Report of the Secretary-General* * Late submission. GE.12-16852 A/HRC/21/35 Contents Paragraphs Page I. Introduction ............................................................................................................. 1–6 3 II. Prison reform .......................................................................................................... 7–17 4 III. Fundamental freedoms and civil society ................................................................. 18–28 6 IV. Land and housing rights .......................................................................................... 29–41 9 V. Rule of law .............................................................................................................. 42–58 12 VI. Public information and human rights education ...................................................... 59–62 15 VII. Reporting and follow-up ......................................................................................... 63–64 16 VIII. Staffing ............................................................................................................... -

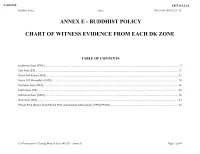

Buddhist Policy Chart of Witness Evidence from Each

ERN>01462446</ERN> E457 6 1 2 14 Buddhist Policy Annex 002 19 09 200 7 ECCC TC ANNEX E BUDDHIST POLICY CHART OF WITNESS EVIDENCE FROM EACH DK ZONE TABLE OF CONTENTS Southwest Zone [SWZ] 2 East Zone [EZ] 12 Sector 505 Kratie [505S] 21 Sector 105 Mondulkiri [105S] 24 Northeast Zone [NEZ] 26 North Zone [NZ] 28 Northwest Zone [NWZ] 36 West Zone [WZ] 43 Phnom Penh Special Zone Phnom Penh Autonomous Municipality [PPSZ PPAM] 45 ’ Co Prosecutors Closing Brief in Case 002 02 Annex E Page 1 of 49 ERN>01462447</ERN> E457 6 1 2 14 Buddhist Policy Annex 002 19 09 200 7 ECCC TC SOUTHWEST ZONE [SWZ] Southwest Zone No Name Quote Source Sector 25 Koh Thom District Chheu Khmau Pagoda “But as in the case of my family El 170 1 Pin Pin because we were — we had a lot of family members then we were asked to live in a monk Yathay T 7 Feb 1 ” Yathay residence which was pretty large in that pagoda 2013 10 59 34 11 01 21 Sector 25 Kien Svay District Kandal Province “In the Pol Pot s time there were no sermon El 463 1 Sou preached by monks and there were no wedding procession We were given with the black Sotheavy T 24 Sou ” 2 clothing black rubber sandals and scarves and we were forced Aug 2016 Sotheavy 13 43 45 13 44 35 Sector 25 Koh Thom District Preaek Ph ’av Pagoda “I reached Preaek Ph av and I saw a lot El 197 1 Sou of dead bodies including the corpses of the monks I spent overnight with these corpses A lot Sotheavy T 27 of people were sick Some got wounded they cried in pain I was terrified ”—“I was too May 2013 scared to continue walking when seeing these -

October 2020 Monthly Meeting Held Under High Presidency of Senior Minister His Excellency Ieng Mouly

October 2020 Monthly Meeting Held Under High Presidency of Senior Minister His Excellency Ieng Mouly Senior Minister His Excellency Ieng Mouly, Chair of the National AIDS Authority, presided over the Authority’s October 2020 monthly meeting at the NAA Headquarters on the morning of Monday, November 2, 2020. In attendance at the meeting were Excellencies, Lok Chumteavs, ladies, and gentlemen, who are vice chairs, advisers, secretary general, director of cabinet, deputy director of cabinet, secretaries general, directors and deputy directors of departments, and heads and deputy heads of offices in a total number of 45 attendees (including five women). The purpose of the meeting was to review the results of work activities undertaken by the NAA top management and officials. Starting the meeting, His Excellency the Senior Minister welcomed all the public servants for their attendance and informed them of the items on the agenda as follows: I) Presentation, given by Secretary General HE Chhim Khindareth, on the summary report on the results of the work activities undertaken by the top management and Secretariat General in October. II) Presentation on the results on the training in the preparation of the action plan and budget integration for responding to HIV and AIDS into the commune and sangkat development plan and investment program in the eight districts of Kampong Speu Province. A. Purpose of training: - To provide communes and sangkats with sufficient capacity and possibility of taking part in ending AIDS in Cambodia by 2025. - To enable the communes and sangkats to be cognizant of the epidemic situation as well as the objective of HIV response and intervention. -

List of Health Facilities Signed the Agreement for Occupational Risk Scheme with the National Social Security Fund

LIST OF HEALTH FACILITIES SIGNED THE AGREEMENT FOR OCCUPATIONAL RISK SCHEME WITH THE NATIONAL SOCIAL SECURITY FUND No. Health Facility Ambulance Contact Phone Number of NSSF Agent Address of Health Facility 1-Phnom Penh 017 808 119 (Morning Shift: Monday-Friday) 098 509 017 449 119 390/010 579 230 (Afternoon Shift: Monday-Friday) 012 455 398 Lot 3, Preah Monivong Boulevard, Sangkat Sras 1 Calmette Hospital 119 012 277 141 (Night Shift: Monday-Friday) 012 243 471 Chok, Khan Doun Penh, Phnom Penh 023 426 948 (Saturday-Sunday) 092 151 845/070 301 655 023 724 891 (Saturday-Sunday) 093 946 637/077 937 337 (Morning Shift: Monday-Friday) 017 378 456/092 571 346/095 792 005 012 657 653 (Afternoon Shift: Monday-Friday) 069 858 #188, St. 271, Sangkat Tek Thla 2, Khan Toul 2 Preak Kossamak Hospital 119 806/015 947 217 016 909 774 (Night Shift: Monday-Friday) 012 846 504 Kork, Phnom Penh (Saturday-Sunday) 086 509 015/078 321 818/017 591 994 078 997 978 (Morning Shift: Monday-Friday) 012 353 089 927 777 916/089 299 309/098 784 403 Khmer-Soviet Friendship 119 (Afternoon Shift: Monday-Friday) 070 763 St. 271, Sangkat Tumnoup Tek, Khan Chamkar 3 012 882 744 Hospital 078 997 978 864/088 688 4076/069 320 023/017 591 994 Mon, Phnom Penh 023 217 764 (Saturday-Sunday) 017 334 458/086 859 867 012 858 184 (Saturday-Sunday) 070 408 600 096 883 878 (Morning Shift: Monday-Friday) 010 264 017/070 722 050/089 454 349/086 563 970 011 811 581 (Afternoon Shift: Monday-Friday) 093 915 Preah Norodom Boulevard, Sangkat Psar Thmey 4 Preah Ang Duong Hospital 016 505 453 070 945 050 210/071 930 9612 1, Khan Doun Penh, Phnom Penh (Night Shift: Monday-Friday) 031 222 1230 011 755 119 (Saturday-Sunday) 010 378 840/077 378 077 550 017 840/069 369 102/070 969 008 National Maternal and Child 012 878 283 #31A, St.47, Sangkat Sras Chok, Khan Doun 5 N/A 096 397 0633 Health Center (Deputy Director ) Penh, Phnom Penh 119 011 833 339 012 918 159 St. -

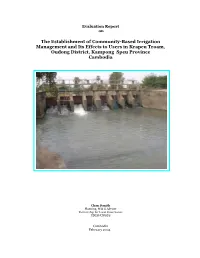

The Establishment of Community-Based Irrigation Management and Its Effects to Users in Krapeu Troam, Oudong District, Kampong Speu Province Cambodia

Evaluation Report on The Establishment of Community-Based Irrigation Management and Its Effects to Users in Krapeu Troam, Oudong District, Kampong Speu Province Cambodia Chan Danith Planning, M & E Adviser Partnership for Local Governance UNDP-UNOPS Cambodia February 2004 Table of Contents Page Table of Contents....................................................................................................... 2 Acknowledgment ....................................................................................................... 3 Abbreviations and Acronyms..................................................................................... 4 List of Table and Figure............................................................................................. 4 1. Introduction .............................................................................................................. 5 2. Evolution of the Irrigation System ........................................................................... 5 3. WUFC Committee Structure ..................................................................................... 6 4. Study Areas and Research Framework ..................................................................... 6 5. Evaluation Team, Trainings and Arrangements....................................................... 7 6. Findings ..................................................................................................................... 9 6.1 Respondent Information and Physical Characteristics ........................................... -

Microsoft Office 2000

mCÄmNÐlÉkßrkm<úCa List of Documented Methods or Types of Torture Compiled by Ry Lakana No Document Position in 1975-1979 Methods or Types of Torture Date of Place of Interview Interview 1 D24817 Interrogator at S-21 Suffocated with plastic bags, beaten with Jan 26, 2001 Smao-khnhei village, Trapaing Sap commune, tree branches, pulling out fingernails, Baty district, Takeo province holding prisoner's heads under water as well. 2 D24822 Prisoner at Snay Pol Blindfolded with cloth or scarf and shot April 19, 2001 Ta-Chou village, Sarikakeo commune, Lvea from behind, cut the throat using palm Em district, Kandal Province ribs. 3 D24826 Chief of guard at S-21 Prisoners were beaten. Feb 12, 2001 Anlong Tasan village, Prek Sdey commune, Koh Thom district, Kandal Province 4 D25046 Guard at S-21 Electrocution Dec 18, 1999 Lvea village, Pech Changva commune, Boribo district, Kampong Chhnang Province 5 D25047 Guard at S-21 Blindfolded with cloth or scarf and beaten Dec 17, 1999 Kraing Korkoh village, Pech Changva commune, Boribo district, Kampong Chhnang Province 6 D25048 Guard at S-21 Introduced water into mouth while Dec 18, 1999 Lvea village, Pech Changva commune, Boribo blindfolded district, Kampong Chhnang Province 7 D25049 Guard at S-21 Clubbing and electrocution, shot, bodies Dec 27, 1999 Sa Poa village, Ta Ches commune, Kampong burned (foreigner) Tralach district, Kampong Chhnang Province 8 D25051 Guard at S-21 Electrocution, abdominal surgery, cut the Dec 18, 1999 Ponlai village, Popel commune, Boribo throat, beaten with iron bars district, -

Battambang Province

Table of contents Page 1 Introduction ................................ ......................................................................................................................... 2 Banteay Mean Chey Province ................................ .............................................................................................. 5 Battambang Province ................................ ........................................................................................................... 8 Kaeb Province .................................................................................................................................................... 12 Kampot Province ................................ ................................................................................................................ 15 Kandal Province ................................ .................................................................................................................. 18 Koh Kong Province ................................ ............................................................................................................. 21 Kompong Cham Province ................................ ................................................................................................... 24 Kompong Chhnang Province ................................ .............................................................................................. 28 Kompong Som Province ................................ .................................................................................................... -

Starting Mental Health Services in Cambodia

PERGAMON Social Science & Medicine 48 (1999) 1029±1046 Starting mental health services in Cambodia Daya J. Somasundaram a, b, c, Willem A.C.M. van de Put a, b, *, Maurice Eisenbruch d, e, Joop T.V.M. de Jong f aCommunity Mental Health Program TPO, Phnom Penh, Cambodia bRoyal University of Phnom Penh, Phnom Penh, Cambodia cUniversity of Jana, Colombo Sri Lanka dPhnom Penh University, Phnom Penh, Cambodia eCentre d'Anthropologie de la Chine du Sud et de la PeÂninsule Indochinoise, Centre National de la Recherche Scienti®que, Paris, France fFree University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, Netherlands Abstract Cambodia has undergone massive psychosocial trauma in the last few decades, but has had virtually no western- style mental health services. For the ®rst time in Cambodia a number of mental health clinics in rural areas have been started. This experience is used to discuss the risks and opportunities in introducing these services in the present war-torn situation. Basic statistics from the clinics are presented in the context of the historical and traditional setting, and the eort to maintain a culturally informed approach is described. The contrasting results in the clinics are analyzed in relation to factors intrinsic to the health care system and those related to the local population in order to highlight the issues involved in establishing future mental health services, both locally in other provinces and in situations similar to Cambodia. The ecacy of introducing low-cost, basic mental health care is shown, and related to the need to ®nd solutions for prevailing problems on the psychosocial level. They can be introduced with modest means, and can be complementary to local health beliefs and traditional healing.