Rajarshi Shahu Mahavidyalaya (Autonomous), Latur

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Use of Short-Term Group Music Therapy for Female College Students with Depression and Anxiety by Barbara Ashton a Thesis P

The Use of Short-Term Group Music Therapy for Female College Students with Depression and Anxiety by Barbara Ashton A Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Music Approved April 2013 by the Graduate Supervisory Committee: Barbara Crowe, Chair Robin Rio Mary Davis ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY May 2013 ABSTRACT There is a lack of music therapy services for college students who have problems with depression and/or anxiety. Even among universities and colleges that offer music therapy degrees, there are no known programs offering music therapy to the institution's students. Female college students are particularly vulnerable to depression and anxiety symptoms compared to their male counterparts. Many students who experience mental health problems do not receive treatment, because of lack of knowledge, lack of services, or refusal of treatment. Music therapy is proposed as a reliable and valid complement or even an alternative to traditional counseling and pharmacotherapy because of the appeal of music to young women and the potential for a music therapy group to help isolated students form supportive networks. The present study recruited 14 female university students to participate in a randomized controlled trial of short-term group music therapy to address symptoms of depression and anxiety. The students were randomly divided into either the treatment group or the control group. Over 4 weeks, each group completed surveys related to depression and anxiety. Results indicate that the treatment group's depression and anxiety scores gradually decreased over the span of the treatment protocol. The control group showed either maintenance or slight worsening of depression and anxiety scores. -

Exploring the Mental Health Experiences of African, Caribbean, and Black Youth in London, Ontario

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 3-3-2021 2:00 PM Exploring the Mental Health Experiences of African, Caribbean, and Black Youth in London, Ontario Lily Yosieph, The University of Western Ontario Supervisor: Orchard, Treena, The University of Western Ontario A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the Master of Science degree in Health and Rehabilitation Sciences © Lily Yosieph 2021 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Community Health Commons, Health Services Research Commons, Other Psychiatry and Psychology Commons, Other Public Health Commons, Other Rehabilitation and Therapy Commons, and the Public Health Education and Promotion Commons Recommended Citation Yosieph, Lily, "Exploring the Mental Health Experiences of African, Caribbean, and Black Youth in London, Ontario" (2021). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 7682. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/7682 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract This qualitative study explores the mental health experiences of African, Caribbean, and Black (ACB) youth in London, Ontario, investigating how the factors of race, gender, culture, and place have shaped their perceptions and experiences of mental health. The data collection and analysis were conducted using a phenomenological approach and a critical lens informed by feminist, intersectionality, and critical race theories. These data illuminate the ways in which these young people’s attitudes toward mental health and help-seeking strategies are impacted by broader social constructs and community expectations, which they navigate and often resist in their everyday lives. -

I Have a Dream: Martin Luther King, Jr. Handbook of Activities

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 299 190 SO 019 326 AUTHOR Duff, Ogle Burks, Ed.; Bowman, Suzanne H., Ed. TITLE I Have a Dream. Martin Luther King, Jr. Handbook of Activities. INSTITUTION Pittsburgh Univ., Pa. Race Desegregation Assistance Center. SPONS AGENCY Department of Education, Washington, DC. PUB DATE Sep 87 CONTRACT 600840 NOTE 485p. PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Use Materials (For Learner) (051) Guides - Classroom Use Guides (For Teachers) (052) EDRS PRICE MF02/PC20 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Art Activities; Black Achievement; Black Leadership; Class Activities; Curriculum Guides; Elementary Secondary Education; *English Curriculum; Instructional Materials; *Language Arts; Learning Modules; Lesson Plans; Library Skills; *Music Activities; Resource Units; *Social Studies; Songs; Speeches; *Teacher Developed Materials; Teaching Guides IDENTIFIERS *Kind (Martin Luther Jr) ABSTRACT This handbook is designed by teachers for teachers to share ideas and activities for celebrating the Martin Luther King holiday, as well as to teach students about other famous black leaders throughout the school year. The lesson plans and activities are presented for use in K-12 classrooms. Each lesson plan has a designated subject area, goals, behavioral objectives, materials and resources, suggested activities, and an evaluation. Many plans include student-related materials such as puzzles, songs, supplementary readings, program suggestions, and tests items. There is a separate section of general suggestions and projects for additional activities. The appendices include related materials drawn from other sources, a list of contributing school districts, and a list of contributors by grade level. (DJC) *********************************************************************** * Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made * * from the original document. * *******************************************************************x*** [ MARTIN LUTHER KING, JR. -

Personal Histories in Conflict Resolution

Mitchell Hamline School of Law Mitchell Hamline Open Access DRI Press DRI Projects 12-1-2020 Evolution of a Field: Personal Histories in Conflict Resolution Howard Gadlin Nancy A. Welsh Follow this and additional works at: https://open.mitchellhamline.edu/dri_press Part of the Dispute Resolution and Arbitration Commons Recommended Citation Gadlin, Howard and Welsh, Nancy A., "Evolution of a Field: Personal Histories in Conflict Resolution" (2020). DRI Press. 12. https://open.mitchellhamline.edu/dri_press/12 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the DRI Projects at Mitchell Hamline Open Access. It has been accepted for inclusion in DRI Press by an authorized administrator of Mitchell Hamline Open Access. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Evolution of a Field: Personal Histories in Conflict Resolution Published by DRI Press, an imprint of the Dispute Resolution Institute at Mitchell Hamline School of Law Dispute Resolution Institute Mitchell Hamline School of Law 875 Summit Ave, St Paul, MN 55015 Tel. (651) 695-7676 © 2020 DRI Press. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Library of Congress Control Number: 2020918154 ISBN: 978-1-7349562-0-7 Mitchell Hamline School of Law in Saint Paul, Minnesota has been educating lawyers for more than 100 years and remains committed to innovation in responding to the changing legal market. Mitchell Hamline offers a rich curriculum in advocacy and problem solving. The law school’s Dispute Resolution Insti- tute, consistently ranked in the top dispute resolution programs by U.S. News & World Report, is committed to advancing the theory and practice of conflict resolution, nationally and inter- nationally, through scholarship and applied practice projects. -

Talks on the Enlightened Woman Mystic, Daya OSHO Talks on the Enlightened Woman Mystic, Daya Contents

OSHO Talks on the Enlightened Woman Mystic, Daya OSHO Talks on the Enlightened Woman Mystic, Daya Contents 1 Remembering the Divine 1 2 Love Can Wait for Lifetimes 49 3 The Last Morning Star 93 4 A Pure Flame of Love Hi 5 Going Beyond Time 183 6 Receiving Your Soul 229 7 The Shine of Countless Suns 273 8 Running with Your Whole Heart 317 9 The Golden Alchemy 363 10 Completing the Circle 409 About Osho 449 Further Information 452 n these discourses, Osho calls all who will hear him to go beyond everything they know or have experienced. "The I path of devotion is the path of the heart," he says. "Only the mad succeed there, only those who can laugh and cry with their whole heart, who are not afraid to drink the wine of the divine - because when you drink that wine you will become intoxicated, you will lose all control over your life. Then you will walk when the divine makes you walk, you will stand when the divine lifts you up. And although you are being made to walk, you are being made to stand, your life goes on very beautifully, very blissfully. Right now, your life is nothing but sorrow; then your life will be nothing but bliss. But this happens only when your life is not under your control. And that is the fear." To put aside that fear, to trust, is the beginning of a complete transformation of one's life. Daya and Sahajo were both disciples of the great master, Charandas (1703-1783). -

^^^^M^^^^Mmm^^^^^M COVER COURTESY of MICHAEL LEUNIG

Jn^Mj/ ^^^^M^^^^mMm^^^^^m COVER COURTESY OF MICHAEL LEUNIG •jj :• t •; ^.,' V; 15 March 1976 Semper Floreat Vol. 46 No. 2 Registered for transmission by post. Category B. EDITORIAL: „ „ u .« * So you noticed that Semper in Seventy-six is somewhat different Or does she |udge 'lust' as harmtul too? i can't see anything wrong with than ill been in the past. The most striking difference, of course, is people lusting over each other. I think a strong case can be made for its size, but this change has implications other than just meaning that lusf to be seen as part of a healthy sexual appetite. you how have a more easily readlble magazine. 2. It is virtually impossible to maintain an overtly Homosexual relation The fact that Semper has changed to a magazine size rather than con ship in present day Brisbane. The 'love and joy' still have to be exper tinue the facade of pretending to be a newspaper does not mean that ienced 'in the closet'. Which seems to me to indicate that the status quo we intend to delete news stories. On the contrary. With the help of a of the relationship between gays and the hetero culture is being main number of dissatisfied journalists and other interested people in Bris tained. That status quo is an overwhelming oppression-even from bane, we hope to provide altemative news (i,e. news ignored or squash such allegedly liberated people as Tina Arndt. ed by the established press) so as to provide Brisbanites with a more balanced view of what happens in this state. -

Adventuring with Books: a Booklist for Pre-K--Grade 6. 1997 Edition

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 406 672 CS 215 782 AUTHOR Sutton, Wendy K., Ed. TITLE Adventuring with Books: A Booklist for Pre-K--Grade 6. 1997 Edition. NCTE Bibliography Series. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, Ill. REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-0080-5; ISSN-1051-4740 PUB DATE 97 NOTE 447p.; Foreword by Patricia MacLachlan. For the 1993 (Tenth) Edition, see ED 362 878. Also prepared by the Committee To Revise the Elementary School Booklist. AVAILABLE FROM National Council of Teachers of English, 1111 West Kenyon Road, Urbana, IL 61801-1096; phone: 1-800-369-6283 (Stock No. 00805: $16.95 members, $22.95 nonmembers). PUB TYPE Reference Materials Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MFO1 /PC18 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Adolescent Literature; Annotated Bibliographies; *Childrens Literature; Elementary Education; Fiction; Nonfiction; Picture Books; Poetry; Preschool Education; Reading Interests; *Reading Material Selection; *Recreational Reading IDENTIFIERS Historical Fiction ABSTRACT This book contains descriptions of over 1,200 books published between 1993 and 1995, all chosen for their high quality and their interest to children, parents, teachers, and librarians. Materials described in the book include fiction, nonfiction, poetry, picture books, young adult novels, and interactive CD-ROMs. Individual book reviews in the book include a description of the book's form and content, information on the type and medium of the illustrations, suggestions on how the book might best be incorporated into the elementary school curriculum, and full bibliographic information. A center insert in the book displays photographs of many of the titles, allowing readers to see the quality of the illustrations for themselves. -

ARIA ALBUMS CHART WEEK COMMENCING 20 NOVEMBER, 2017 TW LW TI HP TITLE Artist CERTIFIED COMPANY CAT NO

CHART KEY <G> GOLD 35000 UNITS <P> PLATINUM 70000 UNITS <D> DIAMOND 500000 UNITS TW THIS WEEK LW LAST WEEK TI TIMES IN HP HIGH POSITION * BULLET ARIA ALBUMS CHART WEEK COMMENCING 20 NOVEMBER, 2017 TW LW TI HP TITLE Artist CERTIFIED COMPANY CAT NO. * 1 NEW 1 1 REPUTATION Taylor Swift BIG/UMA 3003310 2 1 5 1 BEAUTIFUL TRAUMA P!nk <P>3 RCA/SME 88985474692 3 3 37 1 ÷ Ed Sheeran <P>6 WAR 9029585903 4 2 2 2 THE THRILL OF IT ALL Sam Smith CAP/EMI 5793507 * 5 NEW 1 5 ENGRAVED IN THE GAME Kerser ABK/WAR ABK007 * 6 NEW 1 6 SYNTHESIS Evanescence SME 88985489632 * 7 24 54 1 CHRISTMAS Michael Buble <D>2 RPS/WAR 9362494697 8 8 6 2 THE SECRET DAUGHTER SEASON TWO (SONGS FROM TH… Jessica Mauboy <G> SME 88985484442 * 9 NEW 1 9 THE LIVE TAPES VOL 4: THE LAST STAND OF THE SYDNEY … Cold Chisel CC/UMA CC017 10 9 2 9 A LOVE SO BEAUTIFUL: ROY ORBISON & THE ROYAL PHIL… Roy Orbison LEG/SME 88985424582 * 11 NEW 1 11 CHANGA Pnau ETC/UMA ETCETCD056 12 4 2 4 CONSCIOUS Guy Sebastian SME 88985487452 13 10 4 2 FLICKER Niall Horan CAP/EMI 6708433 14 13 18 13 AMERICAN TEEN Khalid RCA/SME 88985414322 15 11 13 9 STONEY Post Malone UNI/UMA 5726167 16 14 15 7 ESSENTIAL OILS: THE GREAT CIRCLE GOLD TOUR EDITION Midnight Oil <G> SME 88985468942 17 5 3 5 HEARTBREAK ON A FULL MOON Chris Brown RCA/SME 88985495432 18 16 47 2 MOANA Soundtrack <P> WALT/UMA 8734913 19 21 178 11 THE VERY BEST OF FLEETWOOD MAC Fleetwood Mac <P>8 RHI/WAR 8122736352 20 22 132 1 1989 Taylor Swift <D> BIG/UMA 3799890 21 7 2 7 RED PILL BLUES Maroon 5 INR/UMA 6706808 22 20 8 3 GEMINI Macklemore BDO/WAR BND709632 23 18 30 2 GUARDIANS OF THE GALAXY VOL. -

A BOOKLET BECAME a BOOK Most Songs Were Recorded Live Between 2004 and 2010 at Various Places During the a to Z Shows. These

A BOOKLET BECAME A BOOK Most songs were recorded live between 2004 and 2010 at various places during the A to Z shows. These usually ran over four nights – each night a different song list as I worked my way alphabetically through around a hundred songs. The idea was to present the songs undressed, in many cases close to how they sounded when they were first written, before being arranged with a band. I imagined a nice chunky booklet to accompany the recordings – some storytelling, notes on the songs and influences, and so on. I started writing a few things down and didn’t stop. Two years later I had a book. To replace the booklet that became a book, I decided to assemble pictures that would tell stories another way. I hope you enjoy them. The text on the following pages comes from How to Make Gravy, published by Penguin. PK, May 2010 I spilled my wine at the bottom of the statue of Colonel Light After Don Dunstan you could drink wine at tables on the pavement, just like they did in Europe Michael, Pedro, Paul, Jon and Steve with Exile on Main Street, 1987 ‘Beautiful Dreamer’, the last song Stephen Foster completed, was published the year of his death. It’s still going strong Steve Connolly came from a line of vaudevillians, writers and communists Behind the bowler’s arm Catherine Kelly, big fine girl. No-one on a mobile phone ever snapped her with her head thrown back and laughing The minor key and falsetto were borrowed from Skip James They always came for Bradman ’cause fortune used to hide in the palm of his hand Fads and fashions came and went but Slim stayed Slim for sixty years I saw Died Pretty a number of times after I moved to Sydney…. -

SF Commentary 55/56

® S F COMMENTARY the independent magazine about science fiction JANUARY/OCTOBER 1979 Australia $2 USA/Canada $3 SFC 55/56 TENTH anniversary EDITION AUSTRALIAN SCIENCE FICTION: A NEW BOOM? pages 5 to 45 REGISTERED FOR REGISTERED POSTING AS A PUBLICATION-CATEGORY B' S F C O M M E N T A R Y 5 5 / 5 6 January/October 1979 Australia: $2.00 (double issue) 68 pages $5/5 subscription USA/Canada: $3.00 (double issue) newsstand $6/5 subscription Elsewhere: Australian equivalent I MUST BE TALKING TO MY FRIENDS Editor John Berry Don Ashby Rick Stooker Alexander Doniphan Wallace George Turner Cy Anders 4, 46 and includes I MUST BE TALKING TO OUR FRIENDS, TOO Elaine Cochrane 48 AUSTRALIAN SCIENCE FICTION: A NEW BOOM? A MEATY BOOK FOR INTELLECTUAL CARNIVORES Sneja Gunew discusses Beloved Son, by George Turner 5 SCIENCE FICTION IN AUSTRALIA A complete survey by George Turner 7 ROOMS OF PARADISE-. TW O V IE W S Bruce Gillespie and Henry Gasko 9 THE MAN WHO FILLED THE VOID Bruce Gillespie discusses Envisaged Worlds, Other Worlds, and Alien Worlds, edited by Paul Collins 16 BY OUR FRUITS... Bruce Gillespie discusses The View from the Edge, edited by George Turner 22 TOO MUCH POWER FOR THE IMPOTENT Bruce Gillespie discusses Moon in the Ground, by Keith Antill 25 WHY DID THE SKY WEEP? Rob Gerrand, John Foyster, Lee Harding, and Bruce Gillespie discuss The Weeping Sky, by Lee Harding 30 LIGHT IN THE GREYWORLD Rob Gerrand discusses Displaced Person, by Lee Harding 36 GENTLE ESCAPISM IN PRETTY PASTEL COLOURS Henry Gasko discusses The Luck o f Brin’s Five, by Cherry Wilder 38 AUSTRALIAN SCIENCE FICTION: IS THAT ALL THERE IS? Andrew Whitmore discusses Walkers on the Sky, by David Lake and Future Sanctuary, by Lee Harding 42 Editor and Publisher: Bruce Gillespie, GPO Box 5195AA, Melbourne, Victoria 3001, Australia. -

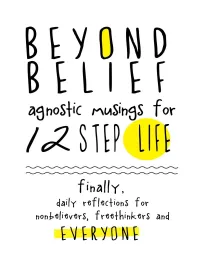

Beyond Belief Is an Inclusive Conversation About Recovery and Addiction

© 2013 Rebellion Dogs Publishing-second printing 2014 All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without the written consent of the publisher. Not sure? Please contact the publisher for permission. Rebellion Dogs Publishing 23 Cannon Road, Unit # 5 Toronto, ON Canada M8Y 1R8 [email protected] http://rebelliondogspublishing.com ISBN # 978-0-9881157-1-2 1. addiction/recovery, 2. self-help, 3. freethinking/philosophy The brief excerpts from Pass it On, Twelve Steps and Twelve Traditions, Living Sober, Alcoholics Anonymous Comes of Age, The Big Book and “Box 4-5-9” are reprinted with permission from Alcoholics Anonymous World Services, Inc. (“AAWS”) Permission to reprint these excerpts does not mean that AAWS has reviewed or approved the contents of this publication, or that AAWS necessarily agrees with the views expressed herein. A.A. is a program of recovery from alcoholism only—use of these excerpts in connection with programs and activities which are patterned after A.A., but which address other problems, or in any other non- A.A. context, does not imply otherwise. Additionally, while A.A. is a spiritual program, A.A. is not a religious program. Thus, A.A. is not affiliated or allied with any sect, denomination, or specific religious belief. See our end notes and bibliography for more referenced material contained in these pages. ABOUT THIS BOOK: It doesn’t matter how much we earn, who we know, our education or what we believe. We are all susceptible to process or substance addiction. -

Harlem Renaissance Unit Resource Handbook for Middle School

Poetry Unit Middle School Harlem Renaissance Unit Written by: Deborah Dennard ELA Coordinator 6-12 Bibb County School District Unit Focus and Direction This unit of study focuses on the Harlem Renaissance. Students are to be immersed in the literature, art, dance, and music of this period. The short stories and literature is meant to be used for the literary standards. The essays and speeches are meant to be taught, using the reading informational standards. Students are to demonstrate mastery of the standards by writing poetry or analysis of the works. Speaking and listening is also an intricate part of this using. While it is important to include poetry in every unit of study, at times, it can be fun to focus solely on poetry. During this unit (2-4 weeks), students are immersed in poetry. They speak, listen to, write, and read poetry – individually and in groups. This sample unit framework can be used for middle and high school. Links are embedded at the end of each piece of reading. To build engagement, please play the videos beforehand to build schema and background knowledge. Poetry is meant to be read, heard, and enjoyed, rather than “studied.” Throughout the unit, read poems aloud daily and encourage students to read aloud poems of their choice. Ask students to respond to the words they hear and read in poems, and to picture the images that the words create. Students may say, “I don’t get it,” and say that they do not like poetry because they are fearful that they do not understand the “correct meaning.” For some of us as teachers, we share the same fear.