Harlem Renaissance Unit Resource Handbook for Middle School

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Citizens Coinage Advisory Committee

Citizens Coinage Advisory Committee Public Meeting Monday, April 19, 2013, 9:30 AM United State Mint Headquarters 801 9th Street NW, 2nd Floor Conference Room Washington, D.C. In attendance: Erik Jansen Gary Marks (Chair) Michael Moran Michael Olson Michael Ross Donald Scarinci Jeanne Stevens-Sollman Thomas Uram Heidi Wastweet 1. Chairperson Marks called the meeting to order at 9:12 A.M. 2. The letters and minutes of the March 11, 2012 meeting were unanimously approved. 3. April Stafford of the United States Mint presented the candidate reverse designs for the 2014 Presidential $1 Coin Program. 4. After each member had commented on the candidate designs, Committee members rated proposed designs by assigning 0, 1, 2, or 3 points to each, with higher points reflecting more favorable evaluations. With nine (9) members voting, the maximum possible point total was twenty-seven (27). The committee’s scores for the 2014 Presidential $1 Coin Program: Warren G. Harding Obverse: WH-01: 0 WH-02: 1 WH-03: 15 WH-04: 0 WH-05: 0 WH-06: 4 WH-07: 21 (Recommended design) Calvin Coolidge Obverse: CC-01: 0 CC-02: 0 CC-03: 6 CC-04: 8 CC-05: 0 CC-06: 19 (Recommended design) Herbert Hoover Obverse: HH-01: 12 HH-02: 5 HH-03: 2 HH-04: 0 HH-05: 17 (Recommended design) HH-06: 3 HH-07: 2 Franklin Delano Roosevelt Obverse: FDR-01: 17 (Recommended design) FDR-02: 11 FDR-03: 0 FDR-04: 0 FDR-05: 0 FDR-06: 10 FDR-07: 1 FDR-08: 0 5. -

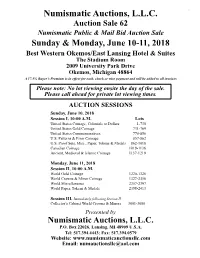

Numismatic Auctions, L.L.C. P.O

NumismaticNumismatic Auctions, LLC Auctions, Auction Sale 62 - June 10-11, 2018 L.L.C. Auction Sale 62 Numismatic Public & Mail Bid Auction Sale Sunday & Monday, June 10-11, 2018 Best Western Okemos/East Lansing Hotel & Suites The Stadium Room 2009 University Park Drive Okemos, Michigan 48864 A 17.5% Buyer’s Premium is in effect for cash, check or wire payment and will be added to all invoices Please note: No lot viewing onsite the day of the sale. Please call ahead for private lot viewing times. AUCTION SESSIONS Sunday, June 10, 2018 Session I, 10:00 A.M. Lots United States Coinage , Colonials to Dollars 1-730 United States Gold Coinage 731-769 United States Commemoratives 770-856 U.S. Patterns & Error Coinage 857-862 U.S. Proof Sets, Misc., Paper, Tokens & Medals 862-1018 Canadian Coinage 1019-1136 Ancient, Medieval & Islamic Coinage 1137-1219 Monday, June 11, 2018 Session II, 10:00 A.M. World Gold Coinage 1220-1326 World Crowns & Minor Coinage 1327-2356 World Miscellaneous 2357-2397 World Paper, Tokens & Medals 2398-2413 Session III, Immediately following Session II Collector’s Cabinet World Crowns & Minors 3001-3080 Presented by Numismatic Auctions, L.L.C. P.O. Box 22026, Lansing, MI 48909 U.S.A. Tel: 517.394.4443; Fax: 517.394.0579 Website: www.numismaticauctionsllc.com Email: [email protected] Numismatic Auctions, LLC Auction Sale 62 - June 10-11, 2018 Numismatic Auctions, L.L.C. Mailing Address: Tel: 517.394.4443; Fax: 517.394.0579 P.O. Box 22026 Email: [email protected] Lansing, MI 48909 U.S.A. -

Amanda Gorman

1. Click printer icon (top right or center bottom). 2. Change "destination"/printer to "Save as PDF." English Self-Directed Learning Activities 3. Click "Save." Language Learning Center 77-1005, Passport Rewards SL53. Interesting People – Amanda Gorman SL 53. Interesting People – Amanda Gorman Student Name: _________________________________ Student ID Number: ________________________ Instructor: _____________________________________ Level: ___________Date: ___________________ For media links in this activity, visit the LLC ESL Tutoring website for Upper Level SDLAs. Find your SDLA number to see all the resources to finish your SDLA. Section 1: What is Interesting? Mark everything in the list below that you find interesting. Definition of Interesting from Longman’s Dictionary of Contemporary English: “if something is interesting, you give it your attention because it seems unusual or exciting or provides information that you did not know about.” Key vocabulary words are given in the next section. Having a twin sister. Writing poetry. Writing poetry and performing it for Michelle Obama, Nike ads, and the Super Bowl, to name a few. Being raised by a single mother in Los Angeles (L.A.) who is a middle school teacher in Watts. Being Black. Being a Black activist. Overcoming a speech impediment. Winning the first ever offered US National Youth Poet Laureate at 19-years-old. Winning the first ever offered L.A. Youth Poet Laureate at 16. Starting a nonprofit organization that encourages youth leadership and poetry workshops. Starting a nonprofit organization when 16 years old. Attending Harvard and graduating with a GPA over 3.5 (cum laude). Speaking at the US Presidential Inauguration. Being the youngest poet to ever present at a Presidential Inauguration. -

Standing Confident and Assured, She Took the Podium to Recite Her Poetry

Standing confident and assured, she took the podium to recite her poetry. Amanda Gorman, first national youth poet laureate of the United States, raised by a single mother, Harvard graduate, stood at the microphone safely distant and unmasked so that those listening could hear her powerful words delivered with passion. In her poem “The Hill We Climb” Gorman spoke into the time and circumstances of her life as young African-American woman with her words of honesty and hope. As she was in the process of writing that poem for President Joe Biden’s inauguration, a violent mob, stoked to anger by the damaging words of a man holding on to his power, stormed the Capitol in Washington, DC. Though the context of her poem was a moment of political transition in another country, Gorman’s words reached out across borders. She said that in writing her poem, her intent was speak healing into division. Not shying away from her country’s racist and colonial history, its struggles, and also its dreams, her words ultimately landed on hope for all people: Scripture tells us to envision that everyone shall sit under their own vine and fig tree and no one shall make them afraid. 1 Mark’s gospel this morning tells us of Jesus’ message and the call of those first disciples. But the story begins with words which hang ominously in the air: “Now after John was arrested.” Right at the beginning of Mark’s account there arises that very brief mention of John the Baptist’s arrest. Mark doesn’t explain the arrest until we get to chapter six of his gospel account. -

Chapter 18: Roosevelt and the New Deal, 1933-1939

Roosevelt and the New Deal 1933–1939 Why It Matters Unlike Herbert Hoover, Franklin Delano Roosevelt was willing to employ deficit spending and greater federal regulation to revive the depressed economy. In response to his requests, Congress passed a host of new programs. Millions of people received relief to alleviate their suffering, but the New Deal did not really end the Depression. It did, however, permanently expand the federal government’s role in providing basic security for citizens. The Impact Today Certain New Deal legislation still carries great importance in American social policy. • The Social Security Act still provides retirement benefits, aid to needy groups, and unemployment and disability insurance. • The National Labor Relations Act still protects the right of workers to unionize. • Safeguards were instituted to help prevent another devastating stock market crash. • The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation still protects bank deposits. The American Republic Since 1877 Video The Chapter 18 video, “Franklin Roosevelt and the New Deal,” describes the personal and political challenges Franklin Roosevelt faced as president. 1928 1931 • Franklin Delano • The Empire State Building 1933 Roosevelt elected opens for business • Gold standard abandoned governor of New York • Federal Emergency Relief 1929 Act and Agricultural • Great Depression begins Adjustment Act passed ▲ ▲ Hoover F. Roosevelt ▲ 1929–1933 ▲ 1933–1945 1928 1931 1934 ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ 1930 1931 • Germany’s Nazi Party wins • German unemployment 1933 1928 107 seats in Reichstag reaches 5.6 million • Adolf Hitler appointed • Alexander Fleming German chancellor • Surrealist artist Salvador discovers penicillin Dali paints Persistence • Japan withdraws from of Memory League of Nations 550 In this Ben Shahn mural detail, New Deal planners (at right) design the town of Jersey Homesteads as a home for impoverished immigrants. -

Kamala Harris and Amanda Gorman

MARCH 2021 WOMEN OF INFLUENCE: Kamala Harris and Amanda Gorman TABLE OF CONTENTS Video Summary & Related Content 3 Video Review 4 Before Viewing 5 Talk Prompts 6 Digging Deeper 8 Activity: Poetry Analysis 13 Sources 14 News in Review is produced by Visit www.curio.ca/newsinreview for an CBC NEWS and Curio.ca archive of all previous News In Review seasons. As a companion resource, go to GUIDE www.cbc.ca/news for additional articles. Writer: Jennifer Watt Editor: Sean Dolan CBC authorizes reproduction of material VIDEO contained in this guide for educational Host: Michael Serapio purposes. Please identify source. Senior Producer: Jordanna Lake News In Review is distributed by: Supervising Manager: Laraine Bone Curio.ca | CBC Media Solutions © 2021 Canadian Broadcasting Corporation WOMEN OF INFLUENCE: Kamala Harris and Amanda Gorman Video duration – 14:55 In January 2021, Kamala Harris became the highest-ranking woman in U.S. history when she was sworn in as the first female vice-president — and the first Black woman and person of South Asian descent to hold the position. Born in California, Harris has ties to Canada having attended high school in Montreal. Another exciting voice heard at the U.S. presidential inauguration was a young woman who may well be changing the world with her powerful words. Amanda Gorman, 23, is an American poet and activist. In 2017, she became the first person in the U.S. to be named National Youth Poet Laureate. This is a look at these two Women of Influence for 2021. Related Content on Curio.ca • News in Review, December 2020 – U.S. -

The Use of Short-Term Group Music Therapy for Female College Students with Depression and Anxiety by Barbara Ashton a Thesis P

The Use of Short-Term Group Music Therapy for Female College Students with Depression and Anxiety by Barbara Ashton A Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Music Approved April 2013 by the Graduate Supervisory Committee: Barbara Crowe, Chair Robin Rio Mary Davis ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY May 2013 ABSTRACT There is a lack of music therapy services for college students who have problems with depression and/or anxiety. Even among universities and colleges that offer music therapy degrees, there are no known programs offering music therapy to the institution's students. Female college students are particularly vulnerable to depression and anxiety symptoms compared to their male counterparts. Many students who experience mental health problems do not receive treatment, because of lack of knowledge, lack of services, or refusal of treatment. Music therapy is proposed as a reliable and valid complement or even an alternative to traditional counseling and pharmacotherapy because of the appeal of music to young women and the potential for a music therapy group to help isolated students form supportive networks. The present study recruited 14 female university students to participate in a randomized controlled trial of short-term group music therapy to address symptoms of depression and anxiety. The students were randomly divided into either the treatment group or the control group. Over 4 weeks, each group completed surveys related to depression and anxiety. Results indicate that the treatment group's depression and anxiety scores gradually decreased over the span of the treatment protocol. The control group showed either maintenance or slight worsening of depression and anxiety scores. -

Exploring the Mental Health Experiences of African, Caribbean, and Black Youth in London, Ontario

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 3-3-2021 2:00 PM Exploring the Mental Health Experiences of African, Caribbean, and Black Youth in London, Ontario Lily Yosieph, The University of Western Ontario Supervisor: Orchard, Treena, The University of Western Ontario A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the Master of Science degree in Health and Rehabilitation Sciences © Lily Yosieph 2021 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Community Health Commons, Health Services Research Commons, Other Psychiatry and Psychology Commons, Other Public Health Commons, Other Rehabilitation and Therapy Commons, and the Public Health Education and Promotion Commons Recommended Citation Yosieph, Lily, "Exploring the Mental Health Experiences of African, Caribbean, and Black Youth in London, Ontario" (2021). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 7682. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/7682 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract This qualitative study explores the mental health experiences of African, Caribbean, and Black (ACB) youth in London, Ontario, investigating how the factors of race, gender, culture, and place have shaped their perceptions and experiences of mental health. The data collection and analysis were conducted using a phenomenological approach and a critical lens informed by feminist, intersectionality, and critical race theories. These data illuminate the ways in which these young people’s attitudes toward mental health and help-seeking strategies are impacted by broader social constructs and community expectations, which they navigate and often resist in their everyday lives. -

I Have a Dream: Martin Luther King, Jr. Handbook of Activities

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 299 190 SO 019 326 AUTHOR Duff, Ogle Burks, Ed.; Bowman, Suzanne H., Ed. TITLE I Have a Dream. Martin Luther King, Jr. Handbook of Activities. INSTITUTION Pittsburgh Univ., Pa. Race Desegregation Assistance Center. SPONS AGENCY Department of Education, Washington, DC. PUB DATE Sep 87 CONTRACT 600840 NOTE 485p. PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Use Materials (For Learner) (051) Guides - Classroom Use Guides (For Teachers) (052) EDRS PRICE MF02/PC20 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Art Activities; Black Achievement; Black Leadership; Class Activities; Curriculum Guides; Elementary Secondary Education; *English Curriculum; Instructional Materials; *Language Arts; Learning Modules; Lesson Plans; Library Skills; *Music Activities; Resource Units; *Social Studies; Songs; Speeches; *Teacher Developed Materials; Teaching Guides IDENTIFIERS *Kind (Martin Luther Jr) ABSTRACT This handbook is designed by teachers for teachers to share ideas and activities for celebrating the Martin Luther King holiday, as well as to teach students about other famous black leaders throughout the school year. The lesson plans and activities are presented for use in K-12 classrooms. Each lesson plan has a designated subject area, goals, behavioral objectives, materials and resources, suggested activities, and an evaluation. Many plans include student-related materials such as puzzles, songs, supplementary readings, program suggestions, and tests items. There is a separate section of general suggestions and projects for additional activities. The appendices include related materials drawn from other sources, a list of contributing school districts, and a list of contributors by grade level. (DJC) *********************************************************************** * Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made * * from the original document. * *******************************************************************x*** [ MARTIN LUTHER KING, JR. -

Langston Hughes

Classic Poetry Series Langston Hughes - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: PoemHunter.Com - The World's Poetry Archive Langston Hughes (February 1, 1902 – May 22, 1967) an American poet, social activist, novelist, playwright, and columnist. He was one of the earliest innovators of the then-new literary art form jazz poetry. Hughes is best known for his work during the Harlem Renaissance. He famously wrote about the period that "Harlem was in vogue." Biography Ancestry and Childhood Both of Hughes' paternal and maternal great-grandmothers were African-American, his maternal great-grandfather was white and of Scottish descent. A paternal great-grandfather was of European Jewish descent. Hughes's maternal grandmother Mary Patterson was of African-American, French, English and Native American descent. One of the first women to attend Oberlin College, she first married Lewis Sheridan Leary, also of mixed race. Lewis Sheridan Leary subsequently joined John Brown's Raid on Harper's Ferry in 1859 and died from his wounds. In 1869 the widow Mary Patterson Leary married again, into the elite, politically active Langston family. Her second husband was Charles Henry Langston, of African American, Native American, and Euro-American ancestry. He and his younger brother John Mercer Langston worked for the abolitionist cause and helped lead the Ohio Anti-Slavery Society in 1858. Charles Langston later moved to Kansas, where he was active as an educator and activist for voting and rights for African Americans. Charles and Mary's daughter Caroline was the mother of Langston Hughes. Langston Hughes was born in Joplin, Missouri, the second child of school teacher Carrie (Caroline) Mercer Langston and James Nathaniel Hughes (1871–1934). -

With Poor Immigrants to America

Library of Congress With poor immigrants to America. WITH POOR IMMIGRANTS TO AMERICA ·The MMCo.· THE MACMILLAN COMPANY NEW YORK·BOSTON·CHICAGO·DALLAS ATLANTA·SAN FRANCISCO MACMILLAN & CO., Limited LONDON·BOMBAY·CALCUTTA MELBOURNE THE MACMILLAN CO. OF CANADA, Ltd. TORONTO WITH POOR IMMIGRANTS TO AMERICA BY STEPHEN GRAHAM AUTHOR OF “WITH THE RUSSIAN PILGRIMS TO JERUSALEM” WITH 32 ILLUSTRATIONS FROM PHOTOGRAPHS BY THE AUTHOR LC New York THE MACMILLAN COMPANY 1914 All rights reserved Copyright, 1914, By HARPER AND BROTHERS. Copyright, 1914, By THE MACMILLAN COMPANY. With poor immigrants to America. http://www.loc.gov/resource/lhbtn.15813 Library of Congress Set up and electrotyped. Published September, 1914. Norwood Press J. S. Cushing Co.—Berwick & Smith Co. Norwood, Mass., U.S.A. SEP 19 1914 $2.00 © Cl. A379559 no 1 NOTE A translation of this book has appeared serially in Russia before publication in Great Britain and America. The matter has accordingly been copyrighted in Russia. My acknowledgments are due to the Editor of Harper's Magazine for permission to republish the story of the journey. I wish to express my thanks to Mrs. James Muirhead, Miss M. A. Best, and to Mr. J. Cotton Dana, who, with unsparing energy and hospitality, helped me to see America as she is. STEPHEN GRAHAM. Vladikavkaz, Russia. vii CONTENTS PAGE Prologue xi CHAPTER With poor immigrants to America. http://www.loc.gov/resource/lhbtn.15813 Library of Congress I. The Voyage 1 II. The Arrival of the Immigrant 41 III. The Passion of America and the Tradition of Britain 54 IV. Ineffaceable Memories of New York 73 V. -

Index to Volume 29 January to December 2019 Compiled by Patricia Coward

THE INTERNATIONAL FILM MAGAZINE Index to Volume 29 January to December 2019 Compiled by Patricia Coward How to use this Index The first number after a title refers to the issue month, and the second and subsequent numbers are the page references. Eg: 8:9, 32 (August, page 9 and page 32). THIS IS A SUPPLEMENT TO SIGHT & SOUND SUBJECT INDEX Film review titles are also Akbari, Mania 6:18 Anchors Away 12:44, 46 Korean Film Archive, Seoul 3:8 archives of television material Spielberg’s campaign for four- included and are indicated by Akerman, Chantal 11:47, 92(b) Ancient Law, The 1/2:44, 45; 6:32 Stanley Kubrick 12:32 collected by 11:19 week theatrical release 5:5 (r) after the reference; Akhavan, Desiree 3:95; 6:15 Andersen, Thom 4:81 Library and Archives Richard Billingham 4:44 BAFTA 4:11, to Sue (b) after reference indicates Akin, Fatih 4:19 Anderson, Gillian 12:17 Canada, Ottawa 4:80 Jef Cornelis’s Bruce-Smith 3:5 a book review; Akin, Levan 7:29 Anderson, Laurie 4:13 Library of Congress, Washington documentaries 8:12-3 Awful Truth, The (1937) 9:42, 46 Akingbade, Ayo 8:31 Anderson, Lindsay 9:6 1/2:14; 4:80; 6:81 Josephine Deckers’s Madeline’s Axiom 7:11 A Akinnuoye-Agbaje, Adewale 8:42 Anderson, Paul Thomas Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), Madeline 6:8-9, 66(r) Ayeh, Jaygann 8:22 Abbas, Hiam 1/2:47; 12:35 Akinola, Segun 10:44 1/2:24, 38; 4:25; 11:31, 34 New York 1/2:45; 6:81 Flaherty Seminar 2019, Ayer, David 10:31 Abbasi, Ali Akrami, Jamsheed 11:83 Anderson, Wes 1/2:24, 36; 5:7; 11:6 National Library of Scotland Hamilton 10:14-5 Ayoade, Richard