System Design Overview

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Design Review Procedure

IDM UID 2832CF VERSION CREATED ON / VERSION / STATUS 30 Nov 2012 / 3.1/ Approved EXTERNAL REFERENCE MQP Procedure Design Review Procedure This document describes how to conduct IO Design Reviews on ITER Systems. It is applicable to all the Conceptual, Preliminary and Final Design Reviews performed by IO on the ITER Project. Approval Process Name Action Affiliation Author Guigon A. 30-Nov-2012:signed IO/DG/DIP/CIE/TI/SYSA CoAuthor Reviewers Alejaldre C. 19-Dec-2012:recommended IO/DG/SQS Bora D. 04-Dec-2012:recommended Chiocchio S. 03-Dec-2012:recommended IO/DG/DIP/CIE/TI Haange R. 19-Dec-2012:recommended IO/DG/DIP Hawryluk R. 04-Dec-2012:recommended IO/DG/ADM Kondoh M. 12-Dec-2012:recommended IO/DG/DIP/CIE Sands D. 19-Dec-2012:recommended IO/DG/SQS/QA Shirao T. 19-Dec-2012:recommended IO/DG/ODG Bak J.- S. 18-Dec-2012:recommended IO/DG/DIP Alekseev A. 03-Dec-2012:recommended IO/DG/DIP/TKM Merola M. 03-Dec-2012:recommended IO/DG/DIP/TKM/INC Approver Motojima O. 04-Jan-2013:approved IO/DG Document Security: level 1 (IO unclassified) RO: Croset Jean-Philippe Read Access LG: CODAC team, LG: Blanket add right persons, LG: IO Cryogenic Section All, GG: In-kind Management Administration, GG: TBM Committee, LG: IN DA cryogenic collaborator, LG: PBS32 JA, LG: [DOC] Baseline Managers, LG: PBS48 EXT, LG: Cryogenic IN DA PT, LG: Code & Standards external experts, LG: JADA_RH, LG: CDR reviewers, LG: Kraftanlagen, LG: Design Office, LG: SES DR Team, GG: TBM_IM_Teams, LG: FST/TBM staff, LG: IO PA project team, LG: DA PA project team, LG: IO TRO, LG: heatings, -

Design Review Principles and Practice

Design Review Principles and Practice Landscape Institute Inspiring great places Published in 2013 by the Design Council. Cover photo: Granary Square at King’s Cross, © John Sturrock All photos by Design Council unless otherwise stated. Although every care has been taken in preparing this report, no responsibility or liability will be accepted by Design Council, its employees, agents or advisors for its accuracy or completeness. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, copied or transmitted without the prior written consent of the publisher except that the material may be photocopied for non-commercial purposes without permission from the publisher. Contents Foreword 3 The purpose of this guidance document 4 Part One: Principles of Design Review Chapter 1: The essentials of Design Review 6 What is Design Review? 6 Ten principles of Design Review 7 Chapter 2: The role of Design Review in the planning system 8 Design Review and national planning policy 8 How Design Review adds value 9 Chapter 3: Who benefits from Design Review? 10 Local authorities 10 Developers 10 Project design teams 11 Community groups 11 Chapter 4: Local and National Design Review 12 Local Design Review arrangements 12 National Design Review 12 Who reviews what? 12 Part Two: Design Review in practice Chapter 5: Delivering the principles 14 Chapter 6: A robust Design Review process 23 Preparation 23 Review 25 Observers 26 Advice 27 Other practical matters 28 Useful contacts 29 Contents 1 William Gates Building, University of Cambridge, © RMJM Foreword Our standards of design can be so much higher. -

Rome Laboratory Reliability Engineer's Toolkit

Rome Laboratory Reliability Engineer's Toolkit April 1993 j* ROME LABORATORY RELIABILITY ENGINEER'S TOOLKIT April 1993 An Application Oriented Guide for the Practicing Reliability Engineer Systems Reliability Division Rome Laboratory Air Force Materiel Command (AFMC) 525 Brooks Rd. Griffiss AFB, NY 13441-4505 QUICK REFERENCE Quick Reference Application Index How Do I... ? • Understand the Principles of TQM 2 Understand Basic DoD R&M Policy and Procedures 7 Develop Quantitative Requirements Reliability (R) 11 Maintainability (M) 17 Testability (T) 20 • Tailor R&M Task Requirements 23 R&M Task Application/Priorities 25 Develop a Contract Data Requirements List 26 • Specify Information To Be Included in Proposals 28 Evaluate Contractor Proposals 31 Specify Part Stress Derating 37 Determine the Limitations of Common Cooling Techniques 44 Understand Basic Parts Control 46 Identify Key R&M&T Topics for Evaluation at Design Reviews 55 Evaluate Contactor's Method of Managing Critical Items 62 Understand Design Concerns Associated with Dormant Conditions 63 Understand Basic SMT Design Issues 66 Evaluate Power Supply Reliability 67 Determine Part Failure Modes and Mechanisms 69 Evaluate Fiber Optic Reliability 73 Understand R&M&T Analysis Types and Purposes 77 Understand Reliability Prediction Methods 80 Understand Maintainability Prediction Methods 81 Understand Testability Analysis Methods 84 Evaluate a Reliability Prediction Report 85 Evaluate Existing Reliability Data 86 Evaluate a Maintainability/Testability Analysis Report 87 Evaluate a Failure -

Practical Impacts of Design-Build on the Design Engineer

Practical Impacts of Design-Build on the Design Engineer Presented by: Joseph C. Staak, Esq. Smith, Currie & Hancock LLP 2700 Marquis One Tower 245 Peachtree Center Avenue, NE Atlanta, GA 30303-1227 Tel: 404.582.8026 [email protected] www.smithcurrie.com November 2012 NOTES Practical Impacts of Design-Build on the Design Engineer I. INTRODUCTION Project delivery using Design-build has become increasingly popular over the last thirty years. Owners have recognized the advantages of using a single source of responsibility for a project’s design and construction. Many contractors have recognized the popularity of design-build and have made adjustments to their business model allowing them to offer this one-stop system for project delivery. Architects and engineers also recognize that, unless they want to avoid this ever growing segment of the project design market, they too must adapt to working directly with the contractor. Nearly half of all commercial construction in the United States is being awarded using design-build as the project delivery vehicle, and the reasons are obvious. Owners perceive multiple advantages in using design-build. These advantages include, but are not limited to, a single source of responsibility for design and construction, the increased risk design-build transfers to the design- builder, the opportunity to fast track design and construction to reduce the time from concept to completion, and the owner’s ability to take advantage of the design-builder’s expertise in identifying design solutions. Changes in public procurement during the last 20 years have precipitated an explosion in the use of design-build by government agencies. -

Design-Build Contracts As an Alternative Method for the Construction of Public Buildings Sam Niece, P.E., Esq

Design-Build Contracts as an Alternative Method for the Construction of Public Buildings Sam Niece, P.E., Esq. Can a California general law city use design-build? It depends on what you mean by “design-build.” I. What is Design-Build? The term “design-build” refers to a range of alternatives to the traditional project delivery system. A useful way to look at design-build is by what it is not. Traditional design-bid-build is a segmented, sequential process where the owner first contracts with a design professional to prepare detailed, suitable-for-construction plans and specifications (or sometimes has them prepared by its in-house engineers), then uses the detailed plans and specifications to solicit competitive price bids for construction, and finally awards the construction project to the low bidder. In design-build, one entity performs both design and construction under a single contract. Government Code § 14661(b) defines the term as follows: “‘design-build’ means a procurement process in which both the design and construction of a project are procured from a single entity.” Public Contract Code § 20133(c)(2) defines the term in identical language. The American Institute of Architects (AIA) defines the term as “a process in which the Owner contracts directly with one entity that is to provide both design and construction services.” Usually, the design-build contract is awarded by some process other than competitive bidding. Government Code § 14661(d)(3)(A)(i) provides that “[a]ward shall be made to the design-build entity whose proposal is judged as providing the best value in meeting the interest of the department and meeting the objectives of the project.” Public Contract Code § 20133(d)(4)(B) provides that “[a] county may use a design-build competition based upon best value . -

Design Review Application Handbook

design review application handbook Contents Design Review Information Forms Standard Board Review Application Step 1 - Materials Checklist Step 2- Materials Checklist Administrative Design Review Application Materials Checklist January 2010 REVISED: February 2012 Spokane Design Review Application Spokane Design Review Application Page 2 Design Review Information This handbook is intended to help orient project Design Review Recommendations applicants to design review in the City of Spokane and The Design Review Board (DRB) is advisory. includes information on the Standard Board Review Recommendations as to whether a proposal is consistent process as well as the more abbreviated Administrative with the applicable design criteria are forwarded to Design Review process. Applications and submittal the Hearing Examiner, Planning Director, or other checklists for both processes are included at the back of responsible action approving authority. In most cases, the handbook. To help ensure a smooth process with the Board’s recommendation will be adopted or made a timely discussion and collaboration, applicants are condition of permit approval. Exceptions are noted in strongly encouraged to begin the design review process Chapter 17G.040 Design Review Board. while the project is still in the early design stages. It is important to understand that the Design Review Projects Requiring Design Review Board may not waive zoning code requirements. In Generally, projects subject to design review include public order to make good use of everyone’s time during design projects or private projects that have an impact on the review, applicants are encouraged to utilize staff resources public realm. Projects requiring design review are listed regarding permitting requirements. -

Towards a TOC, Lean and Six Sigma Solution for Software Engineering by David J

Feature-Driven Development: towards a TOC, Lean and Six Sigma solution for software engineering By David J. Anderson, Microsoft Corporation, October 2004 Abstract Too often TOC practitioners assume that there is no TOC application for software engineering and jump immediately to the Thinking Processes to find answers for problems in software development. Others believe that the only way TOC can help is generic project management and offer Critical Chain as the solution. “Agile Management for Software Engineering” [Anderson 2003], showed that software development can be modeled as a flow problem and that to do so requires knowledge of how software is constructed – the architecture of software systems. Once modeled as a flow problem, the Drum-Buffer-Rope solution can be applied with great success. Recent developments of so called “agile” methods in software engineering are compatible with TOC teaching and often implement a rudimentary DBR solution without understanding it, from a TOC perspective. Cumulative flow diagrams (CFD’s) from Lean Production can be used to report the flow of value through a DBR software development solution. CFD’s can be used to provide insight into constraints which are otherwise hard to see due to the nature of knowledge work. The data from the CFD’s has been used to develop an understanding of variation in software engineering. The use of Shewhart’s statistical process control, Deming’s Theory of Profound Knowledge and Wheeler’s four states of control are introduced for the assessment of capabilities and management of reduction of variation in the process of software development. Analysis techniques used to model the requirements and architecture are used to measure the capacity of the system and identify the constraint. -

Preservation Construction: Design-Build Versus Design-Bid-Build

PRESERVATION CONSTRUCTION: DESIGN-BUILD VERSUS DESIGN-BID-BUILD by NICHOLAS MICHAEL PATRICK (Under the Direction of Wayde Brown) ABSTRACT This thesis will compare the two major construction delivery systems in their application in preservation construction projects, Design-Build (DB) and Design-Bid-Build (DBB). Several factors of construction influence the choice of DB or DBB delivery systems. What are these factors, and how do they affect final products in the context of preservation construction? These factors will be determined and described based on the author’s personal experience working for Aeon Preservation Services, LLC. on two preservation projects. The projects, the restoration of original cast iron canopies at The Department of Veterans Affairs building and the stone façade restoration at the National Gallery of Art West Building, were both located in Washington, D.C. and are examples of DB and DBB. These projects will be analyzed and compared using case studies. INDEX WORDS: Historic preservation, Preservation construction, Construction, Construction management, Project delivery systems, Design-Build, Design-Bid-Build, The Veterans Affairs building, The National Gallery of Art West Building PRESERVATION CONSTRUCTION: DESIGN-BUILD VERSUS DESIGN-BID-BUILD by NICHOLAS MICHAEL PATRICK AB, The University of Georgia, 2010 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF HISTORIC PRESERVATION ATHENS, GA 2013 © 2013 Nicholas Michael Patrick All Rights Reserved PRESERVATION CONSTRUCTION: DESIGN-BUILD VERSUS DESIGN-BID-BUILD by NICHOLAS MICHAEL PATRICK Major Professor: Wayde Brown Committee: Mark E. Reinberger Scott Messer David Matheny Electronic Version Approved: Maureen Grasso Dean of the Graduate School The University of Georgia August 2013 DEDICATION I would like to dedicate this Masters Thesis to my beloved State of Georgia. -

And Final Design Review (FDR) Criteria Mary Ann Lapham

Pittsburgh, PA 15213-3890 Specifying Initial Design Review (IDR) and Final Design Review (FDR) Criteria Mary Ann Lapham Sponsored by the U.S. Department of Defense © 2006 by Carnegie Mellon University Incomplete Without Accompanying Oral Presentation page 1 Outline Introduction – Rationale for IDR and FDR Definitions Engineering Emphasis IDR and FDR Criteria Applying the Criteria Conclusion © 2006 by Carnegie Mellon University Incomplete Without Accompanying Oral Presentation page 2 Introduction – Rationale for IDR/FDR? 1 Many DoD development programs initial capabilities are prototypes for proof of concept and lingering operational capability for extended evaluation and exploitation System representation developed in Technology Development includes • definition of HW and SW configuration items (CIs) • how functionality is distributed across the CIs • how they interact to provide system level capabilities © 2006 by Carnegie Mellon University Incomplete Without Accompanying Oral Presentation page 3 Introduction – Rationale for IDR/FDR? 2 Need increasingly rigorous architectural reviews of system level capabilities to verify desired emergent properties of the system •security •flexibility • extensibility • reconfigurability • interoperability • and others as identified for particular system Produce documentation of engineering and management areas • “hard”, risk laden, requirements done early in lifecycle with effective risk mitigation plans in place • comprehensive recording of design and decision rationale (tracking why and perhaps how) -

Integrating the Charrette Process Into Engineering Education: a Case Study on a Civil Engineering Capstone Course

AC 2012-3084: INTEGRATING THE CHARRETTE PROCESS INTO EN- GINEERING EDUCATION: A CASE STUDY ON A CIVIL ENGINEER- ING DESIGN CAPSTONE COURSE Dr. Michelle Renee Oswald, Bucknell University Michelle Oswald, a LEED AP, is an Assistant Professor at Bucknell University in the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering. Her focus is in sustainable transportation planning and sustainable engi- neering education. She completed her doctoral degree in civil engineering at the University of Delaware, along with a master’s of civil engineering degree, and a master;s of arts in urban affairs and public policy. She received a bachelor of science in civil and environmental engineering from Lafayette College. Dr. Arthur D. Kney, Lafayette College Arthur D. Kney has been a resident of Bethlehem, Penn. since 1993. He lives with his lovely wife Linda, their brilliant eight-year-old daughter, and two wonderful cats. Kney received his doctorate of philosophy (Ph.D.) in environmental engineering from Lehigh University in 1999 and his professional engineering li- cense in 2007. He is currently serving as an Associate Professor and Department Head in the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering at Lafayette College. Throughout Kney’s career, he has been active in the community, at the local, state, and national level. He has served as chair of the Pennsylvania Water Environment Association (PWEA) research committee, Chair of the Bethlehem Environmental Ad- visory Committee, Vice President of the Lehigh Valley Section of the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE), Secretary of ASCE/Environmental and Water Resources Institute (EWRI) Water Supply Engi- neering Committee, and he has been a member of the AWWA/ASCE WTP Design 4th Edition Steering Committee. -

KELLY COBB, MFA Assistant Professor Department of Fashion and Apparel Studies University of Delaware, Newark, DE 19716 Phone: (302) 831-6132, Email: [email protected]

KELLY COBB, MFA Assistant Professor Department of Fashion and Apparel Studies University of Delaware, Newark, DE 19716 Phone: (302) 831-6132, Email: [email protected] Education 2004 MFA, The University of Florida, Gainesville, FL Focus: Sculpture (Textile Architectures) Alumni Fellowship. 1993 BFA The Maryland Institute, College of Art, Baltimore, MD. Major: Fiber and Material Studies Academic and Research Appointments 2018 Fulbright Specialist, Tactile + Technical: Innovation Museo Ixchel, Guatemala City, Guatemala. 2016-Present Faculty Affiliate, Delaware Environmental Institute (DENIN) The University of Delaware. Newark, DE. 2012-Present Assistant Professor-TT, Department of Fashion and Apparel Studies The University of Delaware. Newark, DE. 2008-2012 Instructor, Department of Fashion and Apparel Studies The University of Delaware. Newark, DE. 2006-2008 Instructor, Fiber Department. The Maryland Institute, College of Art, Baltimore, MD. 2006-2008 Instructor, Fashion Department. Drexel University. Philadelphia, PA. 2004-2008 Instructor, Crafts Department. University of The Arts, Philadelphia, PA. Professional Design Experience 2004-2008 Costume Designer, Headlong Dance Theater, Philadelphia, PA. 2005 Apparel Designer, Fun and Function, Philadelphia, PA. 2004 Studio Assistant, The Fabric Workshop and Museum, Philadelphia, PA. 1998-2000 Design Assistant, Lucy Barnes Corp. New York, NY. 1998-2000 Studio Assistant, E. Powell Designs, New York, NY. Research Interests ● Textile Innovation/Applied Materiality ● Sustainable Approaches to Design ● Creative Process ● Collaboration/Multidisciplinary Projects Creative Scholarship Juried Design Exhibitions (*indicates catalog or proceedings published) *Cobb, K., Lapolla, K. (2018-submitted) Wearable Narrative: A Textile Co-Design Scenario for Well-Being. SDA 2018 International Exhibition In Print. Las Vegas, NM. National. *Cobb, K. , Lopez-Gydosh, D. J., & Orzada, B. T. (2018-accepted). -

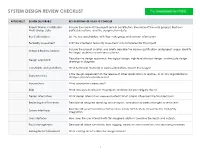

System Design Review Checklist

SYSTEM DESIGN REVIEW CHECKLIST APPLICABLE? DESIGN DELIVERABLE KEY QUESTIONS OR ISSUES TO CONSIDER Project Name, Contributors, Include the name of the project and all contributors, the name of the work group(s) that own Work Group, Date particular sections, and the design review date. Key Stakeholders List the key stakeholders, with their work group and contact information. Feasibility Assessment Indicate whether a feasibility assessment was completed for this project. Include the project charter, and briefly describe the business justification and project scope. Identify Scope & Business Reason the target audience or primary customer. Describe the design approach, the logical design, high-level physical design, and include design Design Approach drawings or diagrams. Constraints and Limitations What technical, financial, or business limitations impact this design? Is the design dependent on the release of other applications or services, or on any organizational Dependencies changes or process bottlenecks? Assumptions What assumptions were used? Risks What risks were involved in this project, and how did you mitigate them? Design Alternatives What design alternatives were evaluated? What criteria influenced the final decision? Reporting and Processes Describe all designed reporting and analytics, and what has been changed or removed? Describe all system interfaces and services, inputs and outputs, as well as any third-party System Interfaces integrations. User Interfaces How does the user interact with this designed solution? Describe the inputs and outputs. Fault Management Describe all failure conditions, error logging, detection and correction, and recovery processes. Existing Defects Resolved What existing defects does this design resolve? 1 SYSTEM DESIGN REVIEW CHECKLIST continued APPLICABLE? DESIGN DELIVERABLE KEY QUESTIONS OR ISSUES TO CONSIDER Describe the regulations that this solution addresses.