Identity Politics in Crimea: Internal Borders in the USSR Between the 1950S and the 1970S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Open Letter of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine

We would highly appreciate if you correctly attribute to Ukraine the publications produced by scientists based in Sevastopol, Simferopol, Kerch, Yalta, Nikita, Feodosia, Nauchny, Simeiz, Yevpatoria, Saki, and other cities and towns of the Crimean region, Donetsk, and Luhansk, in particular the Crimean Laser Observatory of the Main Astronomical Observatory, the Marine Institute of Hydrophysics, the Crimean Nature Reserve, the Karadag Nature Reserve, the O.O.Kovalevsky Institute of Biology of the Southern Seas, the Donetsk O.O.Galkin Institute of Physics and Engineering, and others. We insist on appropriate attributions of Crimean and Donbas research institutions to Ukraine in any publications, especially in international journals. In those cases when items with inappropriate country affiliation have been already published due to neglect or for some other reason, we request the soonest possible publication of corrigenda or editorial notes, explaining the temporary occupied status of the Crimea and the Donbas. In those cases when Crimean or Donbas authors, for fear of repressions, provide for communication reasons their current addresses as Russia or Russian Federation, the editorial disclaimer has to be made indicating the real status of Crimea and Donbas as a constituent and integral part of Ukraine, with proper reference to the relevant international documents adopted by the UN and/or other bodies. An example of such a disclaimer could be as follows: “The author(s) from the Crimea / Donbas of the article(s) appearing in this Journal is/are solely responsible for the indication of his/her/their actual postal address(es) and country affiliation(s). However, the Journal states that the country affiliation(s) indicated in the article is/are improper. -

International Crimes in Crimea

International Crimes in Crimea: An Assessment of Two and a Half Years of Russian Occupation SEPTEMBER 2016 Contents I. Introduction 6 A. Executive summary 6 B. The authors 7 C. Sources of information and methodology of documentation 7 II. Factual Background 8 A. A brief history of the Crimean Peninsula 8 B. Euromaidan 12 C. The invasion of Crimea 15 D. Two and a half years of occupation and the war in Donbas 23 III. Jurisdiction of the International Criminal Court 27 IV. Contextual elements of international crimes 28 A. War crimes 28 B. Crimes against humanity 34 V. Willful killing, murder and enforced disappearances 38 A. Overview 38 B. The law 38 C. Summary of the evidence 39 D. Documented cases 41 E. Analysis 45 F. Conclusion 45 VI. Torture and other forms of inhuman treatment 46 A. Overview 46 B. The law 46 C. Summary of the evidence 47 D. Documented cases of torture and other forms of inhuman treatment 50 E. Analysis 59 F. Conclusion 59 VII. Illegal detention 60 A. Overview 60 B. The law 60 C. Summary of the evidence 62 D. Documented cases of illegal detention 66 E. Analysis 87 F. Conclusion 87 VIII. Forced displacement 88 A. Overview 88 B. The law 88 C. Summary of evidence 90 D. Analysis 93 E. Conclusion 93 IX. Crimes against public, private and cultural property 94 A. Overview 94 B. The law 94 C. Summary of evidence 96 D. Documented cases 99 E. Analysis 110 F. Conclusion 110 X. Persecution and collective punishment 111 A. Overview 111 B. -

Urgently for Publication (Procurement Procedures) Annoucements Of

Bulletin No�1 (180) January 7, 2014 Urgently for publication Annoucements of conducting (procurement procedures) procurement procedures 000162 000001 Public Joint–Stock Company “Cherkasyoblenergo” State Guard Department of Ukraine 285 Gogolia St., 18002 Cherkasy 8 Bohomoltsia St., 01024 Kyiv–24 Horianin Artem Oleksandrovych Radko Oleksandr Andriiovych tel.: 0472–39–55–61; tel.: (044) 427–09–31 tel./fax: 0472–39–55–61; Website of the Authorized agency which contains information on procurement: e–mail: [email protected] www.tender.me.gov.ua Website of the Authorized agency which contains information on procurement: Procurement subject: code DK 016–2010 (19.20.2) liquid fuel and gas; www.tender.me.gov.ua lubricating oils, 4 lots: lot 1 – petrol А–95 (petrol tanker norms) – Procurement subject: code 27.12.4 – parts of electrical distributing 100 000 l, diesel fuel (petrol tanker norms) – 60 000 l; lot 2 – petrol А–95 and control equipment (equipment KRU – 10 kV), 7 denominations (filling coupons in Ukraine) – 50 000,00, diesel fuel (filling coupons in Supply/execution: 82 Vatutina St., Cherkasy, the customer’s warehouse; Ukraine) – 30 000,00 l; lot 3 – petrol А–95 (filling coupons in Kyiv) – till 15.04.2014 60 000,00; lot 4 – petrol А–92 (filling coupons in Kyiv) – 30 000,00 Procurement procedure: open tender Supply/execution: 52 Shcherbakova St., Kyiv; till December 15, 2014 Obtaining of competitive bidding documents: 285 Hoholia St., 18002 Cherkasy, Procurement procedure: open tender the competitive bidding committee Obtaining of -

The Simeiz Fundamental Geodynamics Area

The Simeiz Fundamental Geodynamics Area A. E. Volvach, G. S. Kurbasova Abstract This report gives an overview about the as- 2 Activities during the Past Year and trophysical and geodetic activities at the the fundamen- Current Status tal geodynamics area Simeiz-Katsively. It also summa- rizes the wavelet analysis of the ground and satellite During the past year, the Space Geodesy and Geo- measurements of local insolation on the “Nikita gar- dynamics stations regularly participated in the Inter- den” of Crimea. national Network programs — IVS, the International GPS Service (IGS), and the International Laser Rang- ing Service (ILRS). 1 General Information During the period 2013 January 1 through 2013 December 31, the Simeiz VLBI station participated The Radio Astronomy Laboratory of the Crimean As- in 14 24-hour geodetic sessions. Simeiz regularly trophysical Observatory with its 22-m radio telescope participated in the EUROPE and T2 series of geodetic is located near Simeiz, 25 km to the west of Yalta. The sessions. Simeiz geodynamics area consists of the radio tele- scope RT-22, two satellite laser ranging stations, a per- manent GPS receiver, and a sea level gauge. All these components are located within 3 km (Figure 1). 2.1 Multi-Frequency Molecular Line RT-22, the 22-meter radio telescope, which began Observations operations in 1966, is among the five most efficient telescopes in the world. Various observations in the centimeter and millime- Study of the star-forming regions in molecular lines ter wave ranges are being performed with this tele- started in 1978. Two main types of observation are car- scope now and will be performed in the near future. -

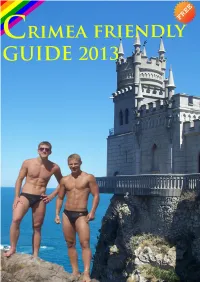

Crimea Guide.Pdf

Crimea Crimean peninsula located on the south of Ukraine, between the Black and Azov Seas. In the southern part of the peninsula located Crimean mountains, more than a kilometer high. Peninsula is connected to the mainland of Ukraine by several isthmuses. The eastern part of Crimea separated from Russia by the narrow Kerch Strait, a width of less then ten kilometers. Crimea - is one of the most interesting places for tourism in Ukraine. On a very small territory - about 26,800 square kilometers, you can find the Sea and the mountains, prairies and lakes, palaces and the ancient city-states, forts and cave cities, beautiful nature and many other interesting places. During two thousand years, the Crimean land often passed from hand to hand. In ancient times, the Greeks colonized Crimea and founded the first cities. After them the Romans came here. After the collapse of the Roman Empire, Crimea became part of the Byzantine Empire. Here was baptized Prince Vladimir who later baptized Kievan Rus. For a long time in the Crimea live together Tatars, Genoese and the small principality Theodoro, but in 1475, Crimea was conquered by the Ottoman Empire. More than three hundreds years the Ottoman Empire ruled the Crimea. After the Russian-Turkish war in 1783, the peninsula became part of the Russian Empire. In 1854-1855 Crimea was occupied forces of Britain, France and Turkey. During the battle near Balaklava death many famous Britons, including Winston Churchill's grandfather. And now, the highest order of the British armed forces - the Victoria Cross minted from metal captured near Balaclava Russian guns. -

Annoucements of Conducting Procurement Procedures

Bulletin No�8(134) February 19, 2013 Annoucements of conducting 002798 Apartments–Maintenance Department of Lviv procurement procedures 3–a Shevchenka St., 79016 Lviv Maksymenko Yurii Ivanovych tel.: (032) 233–05–93 002806 SOE “Makiivvuhillia” Website of the Authorized agency which contains information on procurement: 2 Radianska Sq., 86157 Makiivka, Donetsk Oblast www.tender.me.gov.ua Vasyliev Oleksandr Volodymyrovych Procurement subject: code 35.12.1 – transmission of electricity, 2 lots tel.: (06232) 9–39–98; Supply/execution: at the customer’s address, m/u in the zone of servicing tel./fax: (0623) 22–11–30; of Apartments–Maintenance Department of Lviv; January – December 2013 e–mail: [email protected] Procurement procedure: procurement from the sole participant Website of the Authorized agency which contains information on procurement: Name, location and contact phone number of the participant: lot 1 – PJSC www.tender.me.gov.ua “Lvivoblenergo” Lviv City Power Supply Networks, 3 Kozelnytska St., 79026 Procurement subject: code 71.12.1 – engineering services (development Lviv, tel./fax: (032) 239–20–01; lot 2 – State Territorial Branch Association “Lviv of documentation of reconstruction of technological complex of skip Railway”, 1 Hoholia St., 79007 Lviv, tel./fax: (032) 226–80–45 shaft No.1 of Separated Subdivision “Mine named after V.M.Bazhanov” Offer price: UAH 22015000: lot 1 – UAH 22000000, lot 2 – UAH 15000 (equipment of shaft for works in sump part)) Additional information: Procurement procedure from the sole participant is Supply/execution: Separated Subdivision “Mine named after V.M.Bazhanov” applied in accordance with paragraph 2, part 2, article 39 of the Law on Public of SOE “Makiivvuhillia”; during 2013 Procurement. -

National Report of the Russian Federation

DEPARTMENT OF NAVIGATION AND OCEANOGRAPHY OF THE MINISTRY OF DEFENSE OF THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION NATIONAL REPORT OF THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION 21TH MEETING OF MEDITERRANEAN and BLACKSEAS HYDROGRAPHIC COMMISSION Spain, Cadiz, 11-13 June 2019 1. Hydrographic office In accordance with the legislation of the Russian Federation matters of nautical and hydrographic services for the purpose of aiding navigation in the water areas of the national jurisdiction except the water area of the Northern Sea Route and in the high sea are carried to competence of the Ministry of Defense of the Russian Federation. Planning, management and administration in nautical and hydrographic services for the purpose of aiding navigation in the water areas of the national jurisdiction except the water area of the Northern Sea Route and in the high sea are carried to competence of the Department of Navigation and Oceanography of the Ministry of Defense of the Russian Federation (further in the text - DNO). The DNO is authorized by the Ministry of Defense of the Russian Federation to represent the State in civil law relations arising in the field of nautical and hydrographic services for the purpose of aiding navigation. It is in charge of the Hydrographic office of the Navy – the National Hydrographic office of the Russian Federation. The main activities of the Hydrographic office of the Navy are the following: to carry out the hydrographic surveys adequate to the requirements of safe navigation in the water areas of the national jurisdiction and in the high sea; to prepare -

F:\REJ\16-3\273-279 (Ryndevich)

Russian Entomol. J. 16(3): 273–279 © RUSSIAN ENTOMOLOGICAL JOURNAL, 2007 Beetles of superfamily Hydrophiloidea (Coleoptera: Helophoridae, Hydrochidae, Spercheidae, Hydrophilidae) of the Crimean peninsula Æåñòêîêðûëûå íàäñåìåéñòâà Hydrophiloidea (Coleoptera: Helophoridae, Hydrochidae, Spercheidae, Hydrophilidae) Êðûìñêîãî ïîëóîñòðîâà S.K. Ryndevich Ñ.Ê. Ðûíäåâè÷ Baranovichy State University, Voykova str. 21, Baranovichy 225404, Belarus. E-mail: [email protected] Барановичский государственный университет, ул. Войкова 21, Барановичи 225404, Беларусь. KEY WORDS: Coleoptera, Hydrophiloidea, check-list, Ukraine, Crimean peninsula. КЛЮЧЕВЫЕ СЛОВА: Coleoptera, Hydrophiloidea, аннотированный список, Украина, Крымский полуостров. ABSTRACT: At present the fauna of the superfam- nus Thomson, Cercyon (Cercyon) pygmaeus (Illiger), ilies Hydrophiloidea of the Crimea includes 73 species Cryptopleurum minutum (Fabricius), Cryptopleurum sub- (Helophoridae — 13, Hydrochidae — 2, Spercheidae — tile Sharp, Enochrus (Enochrus) melanocephalus (Olivi- 1, Hydrophilidae — 57). Enochrus (Methydrus) nigri- er), Enochrus (Lumetus) fuscipennis Thomson, Enochrus tus Sharp and Helochares lividus (Foster) are reported (Lumetus) hamifer (Ganglbauer), Enochrus (Lumetus) for Ukraine and the Crimea for the first time. Eighteen quadripunctatus (Herbst), Hydrobius fuscipes (Linnae- species: Helophorus (Helophorus) liguricus Angus, us), Laccobius (Dimorpholaccobius) bipunctatus (Fabri- Helophorus (Rhopalhelophorus) brevipalpis brevipal- cius), Laccobius (Dimorpholaccobius) -

Hijra and Forced Migration from Nineteenth-Century Russia to The

Cahiers du monde russe Russie - Empire russe - Union soviétique et États indépendants 41/1 | 2000 Varia Hijra and forced migration from nineteenth- century Russia to the Ottoman Empire A critical analysis of the Great Tatar emigration of 1860-1861 Brian Glyn Williams Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/monderusse/39 DOI: 10.4000/monderusse.39 ISSN: 1777-5388 Publisher Éditions de l’EHESS Printed version Date of publication: 1 January 2000 Number of pages: 79-108 ISBN: 2-7132-1353-3 ISSN: 1252-6576 Electronic reference Brian Glyn Williams, « Hijra and forced migration from nineteenth-century Russia to the Ottoman Empire », Cahiers du monde russe [Online], 41/1 | 2000, Online since 15 January 2007, Connection on 20 April 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/monderusse/39 ; DOI : 10.4000/monderusse.39 © École des hautes études en sciences sociales, Paris. BRIAN GLYN WILLIAMS HIJRA AND FORCED MIGRATION FROM NINETEENTH-CENTURY RUSSIA TO THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE A critical analysis of the Great Crimean Tatar emigration of 1860-1861 THE LARGEST EXAMPLES OF FORCED MIGRATIONS in Europe since the World War II era have involved the expulsion of Muslim ethnic groups from their homelands by Orthodox Slavs. Hundreds of thousands of Bulgarian Turks were expelled from Bulgaria by Todor Zhivkov’s communist regime during the late 1980s; hundreds of thousands of Bosniacs were cleansed from their lands by Republika Srbska forces in the mid-1990s; and, most recently, close to half a million Kosovar Muslims have been forced from their lands by Yugoslav forces in Kosovo in Spring of 1999. This process can be seen as a continuation of the “Great Retreat” of Muslim ethnies from the Balkans, Pontic rim and Caucasus related to the nineteenth-century collapse of Ottoman Muslim power in this region. -

Late-Holocene Palaeoenvironments of Southern Crimea: Soils, Soil-Climate Relationship and Human Impact

Coversheet This is the accepted manuscript (post-print version) of the article. Contentwise, the accepted manuscript version is identical to the final published version, but there may be differences in typography and layout. How to cite this publication Please cite the final published version: Lisetskii, F. N., Stolba, V., & Pichura, V. I. (2017). Late-Holocene palaeoenvironments of Southern Crimea: Soils, soil-climate relationship and human impact. The Holocene, 27(12), 1859–1875. DOI: 10.1177/0959683617708448 Publication metadata Title: Late-Holocene palaeoenvironments of Southern Crimea: Soils, soil- climate relationship and human impact Author(s): Fedor N. Lisetskii, Vladimir F. Stolba & Vitalii I. Pichura Journal: The Holocene DOI/Link: https://doi.org/10.1177/0959683617708448 Document version: Accepted manuscript (post-print) General Rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognize and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. If the document is published under a Creative Commons license, this applies instead of the general rights. -

Detection and Monitoring of Alien Plant-Sucking Insect Spe- Cies on the Black Sea Coast of Russia †

Proceedings Detection and Monitoring of Alien Plant-Sucking Insect Spe- cies on the Black Sea Coast of Russia † Natalia Karpun1,2, Elena Zhuravleva1, Boris Borisov3, Natalia Kirichenko4,2, Dmitry Musolin2 1 Federal Research Centre the Subtropical Scientific Centre of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Sochi, Russia; [email protected]; [email protected] 2 Saint Petersburg State Forest Technical University, Saint Petersburg, Russia; [email protected] 3 AgroBioTechnology LLC (Production and Research Company), Moscow, Russia; [email protected] 4 Sukachev Institute of Forest, Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Federal Research Center «Krasnoyarsk Science Center SB RAS», Krasnoyarsk, Russia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] † Presented at the 1st International Electronic Conference on Entomology (IECE 2021), 1–15 July 2021; Available online: https://iece.sciforum.net/. Abstract: The Black Sea coast of Russia is a recipient region for many alien insect pests. In 2018, we detected an invasive woolly whitefly Aleurothrixus floccosus (Maskell) (Homoptera: Aleyrodidae) attacking citruses in the agrocenoses and ornamental plantations in the region of Sochi. Further- more, we clarified the secondary range of an alien whitefly, Aleuroclava aucubae (Kuwana) (Homop- tera: Aleyrodidae) in the humid subtropics of Russia. Another plant-sucking invader, the western conifer seed bug Leptoglossus occidentalis Heidemann (Heteroptera: Coreidae) was revealed in the Black Sea coast of Crimea in 2019. Further distribution and trophic associations of these novel alien pests are discussed. Citation: Karpun N.; Zhuravleva E.; Keywords: invasive species, pest, whitefly, western conifer seed bug, Russia, Black Sea coast Borisov B.; Kirichenko N.; Musolin D. Detection and Monitoring of Al- ien Plant-Sucking Insect Species on the Black Sea Coast of Russia. -

The Influence of Major Geopolitical Factors on a Region's Tourist Industry and Perception by Tourists

Cactus Tourism Journal Vol. 12, Issue 2/2015, Pages 22-32, ISSN 2247-3297 THE INFLUENCE OF MAJOR GEOPOLITICAL FACTORS ON A REGION'S TOURIST INDUSTRY AND PERCEPTION BY TOURISTS. CASE STUDY: CRIMEA Constantin Ștefan1 Bucharest University of Economic Studies, Romania ABSTRACT Periodically certain countries or regions of the world are affected by various types of political unrest, such as wars ‒ including civil, revolutions, power struggles etc. In some cases, these regions have significantly developed tourist industries. In case these political events are violent, the result is predictable: a complete or almost complete halt of tourism in the region, most often accompanied by the destruction of the tourist infrastructure. But when these events are not violent, the effects on tourism may vary. As of 2015, the Crimean Peninsula is one of Europe's geopolitical hotspots and one of the world's disputed territories. This reputation comes from the fact that in March 2014 the territory switched sovereignty from Ukraine to Russia, following what many other states have qualified as an invasion and/or an illegally-held referendum. The purpose of this article is to examine the effects this series of events has had on the area's tourist industry. The article features the results of a research based on a survey, which was meant to evaluate the respondents' perception of the region. This survey was conducted among subjects from numerous European and former Soviet countries. The results have shown that there are certain differences in the perception of Crimea between Europe and the former Soviet states. These differences have the potential to shape the tourist industry of the region in the near future.