Crimean Rhetorical Sovereignty: Resisting a Deportation of Identity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Open Letter of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine

We would highly appreciate if you correctly attribute to Ukraine the publications produced by scientists based in Sevastopol, Simferopol, Kerch, Yalta, Nikita, Feodosia, Nauchny, Simeiz, Yevpatoria, Saki, and other cities and towns of the Crimean region, Donetsk, and Luhansk, in particular the Crimean Laser Observatory of the Main Astronomical Observatory, the Marine Institute of Hydrophysics, the Crimean Nature Reserve, the Karadag Nature Reserve, the O.O.Kovalevsky Institute of Biology of the Southern Seas, the Donetsk O.O.Galkin Institute of Physics and Engineering, and others. We insist on appropriate attributions of Crimean and Donbas research institutions to Ukraine in any publications, especially in international journals. In those cases when items with inappropriate country affiliation have been already published due to neglect or for some other reason, we request the soonest possible publication of corrigenda or editorial notes, explaining the temporary occupied status of the Crimea and the Donbas. In those cases when Crimean or Donbas authors, for fear of repressions, provide for communication reasons their current addresses as Russia or Russian Federation, the editorial disclaimer has to be made indicating the real status of Crimea and Donbas as a constituent and integral part of Ukraine, with proper reference to the relevant international documents adopted by the UN and/or other bodies. An example of such a disclaimer could be as follows: “The author(s) from the Crimea / Donbas of the article(s) appearing in this Journal is/are solely responsible for the indication of his/her/their actual postal address(es) and country affiliation(s). However, the Journal states that the country affiliation(s) indicated in the article is/are improper. -

Hier Zum Download

2 Перевод с русского: Александр Алешко Владимир Ильницкий Василий Бондарь Бекир Умеров Верстка-дизайн: Андрей Мельникович Translated by: Aliaksandr Aleshka Volodymyr Ilnytskyi Vasili Bondar Bekir Umerov Designed by: Andrei Melnikovich This Project is realized in the call on „Paths of Remembrance“ of Geschichtswerkstatt Europa. It is one of 24 European projects that is funded by the foundation „Remembrance, Responsibility and Future“. Geschichtswerkstatt Europa is a programme of the foundation „Remembrance, Responsibility and Future“ adressing the issue of European remembrance. The Institute for Applied History coordinates the funding of projects in cooperation with the European University Viadrina. The International Forum is organised by the Global and European Studies Institute at the University of Leipzig. Quoting from: Aleshka, Aliaksandr / Bondar, Vasili / Ilnytskyi, Volodymyr / Umerov,Bekir: Crimean Tatars: Remembrance of Deportation and the Young Generation, in: Geschichstwerkstatt Europa, 01.06.2010. Copyright (c) 2010 by Geschichtswerkstatt Europa and the author, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the author and usage right holders. For permission please contact [email protected]. 3 Dear readers, This publication is a result of the project “Crimean Tatars: Remembrance of Deportation and the Young Generation”. This project was realized in frames of the program „Geschichtswerkstatt Europa”, in as- sistance with the German foundation „EVZ” – “Remembrance, Responsibility and Future”. In frames of this project, international team of 4 people, representing Belarus, Ukraine and Crimean Tatar community, studied the remembrance of Deportation of 1944 by the young generation of Crimean Tatars. The project was conceived as a research of existing patterns of remembrance of Deportation and per- sonal perception of young people of the problem of Deportation. -

International Crimes in Crimea

International Crimes in Crimea: An Assessment of Two and a Half Years of Russian Occupation SEPTEMBER 2016 Contents I. Introduction 6 A. Executive summary 6 B. The authors 7 C. Sources of information and methodology of documentation 7 II. Factual Background 8 A. A brief history of the Crimean Peninsula 8 B. Euromaidan 12 C. The invasion of Crimea 15 D. Two and a half years of occupation and the war in Donbas 23 III. Jurisdiction of the International Criminal Court 27 IV. Contextual elements of international crimes 28 A. War crimes 28 B. Crimes against humanity 34 V. Willful killing, murder and enforced disappearances 38 A. Overview 38 B. The law 38 C. Summary of the evidence 39 D. Documented cases 41 E. Analysis 45 F. Conclusion 45 VI. Torture and other forms of inhuman treatment 46 A. Overview 46 B. The law 46 C. Summary of the evidence 47 D. Documented cases of torture and other forms of inhuman treatment 50 E. Analysis 59 F. Conclusion 59 VII. Illegal detention 60 A. Overview 60 B. The law 60 C. Summary of the evidence 62 D. Documented cases of illegal detention 66 E. Analysis 87 F. Conclusion 87 VIII. Forced displacement 88 A. Overview 88 B. The law 88 C. Summary of evidence 90 D. Analysis 93 E. Conclusion 93 IX. Crimes against public, private and cultural property 94 A. Overview 94 B. The law 94 C. Summary of evidence 96 D. Documented cases 99 E. Analysis 110 F. Conclusion 110 X. Persecution and collective punishment 111 A. Overview 111 B. -

Urgently for Publication (Procurement Procedures) Annoucements Of

Bulletin No�1 (180) January 7, 2014 Urgently for publication Annoucements of conducting (procurement procedures) procurement procedures 000162 000001 Public Joint–Stock Company “Cherkasyoblenergo” State Guard Department of Ukraine 285 Gogolia St., 18002 Cherkasy 8 Bohomoltsia St., 01024 Kyiv–24 Horianin Artem Oleksandrovych Radko Oleksandr Andriiovych tel.: 0472–39–55–61; tel.: (044) 427–09–31 tel./fax: 0472–39–55–61; Website of the Authorized agency which contains information on procurement: e–mail: [email protected] www.tender.me.gov.ua Website of the Authorized agency which contains information on procurement: Procurement subject: code DK 016–2010 (19.20.2) liquid fuel and gas; www.tender.me.gov.ua lubricating oils, 4 lots: lot 1 – petrol А–95 (petrol tanker norms) – Procurement subject: code 27.12.4 – parts of electrical distributing 100 000 l, diesel fuel (petrol tanker norms) – 60 000 l; lot 2 – petrol А–95 and control equipment (equipment KRU – 10 kV), 7 denominations (filling coupons in Ukraine) – 50 000,00, diesel fuel (filling coupons in Supply/execution: 82 Vatutina St., Cherkasy, the customer’s warehouse; Ukraine) – 30 000,00 l; lot 3 – petrol А–95 (filling coupons in Kyiv) – till 15.04.2014 60 000,00; lot 4 – petrol А–92 (filling coupons in Kyiv) – 30 000,00 Procurement procedure: open tender Supply/execution: 52 Shcherbakova St., Kyiv; till December 15, 2014 Obtaining of competitive bidding documents: 285 Hoholia St., 18002 Cherkasy, Procurement procedure: open tender the competitive bidding committee Obtaining of -

The Simeiz Fundamental Geodynamics Area

The Simeiz Fundamental Geodynamics Area A. E. Volvach, G. S. Kurbasova Abstract This report gives an overview about the as- 2 Activities during the Past Year and trophysical and geodetic activities at the the fundamen- Current Status tal geodynamics area Simeiz-Katsively. It also summa- rizes the wavelet analysis of the ground and satellite During the past year, the Space Geodesy and Geo- measurements of local insolation on the “Nikita gar- dynamics stations regularly participated in the Inter- den” of Crimea. national Network programs — IVS, the International GPS Service (IGS), and the International Laser Rang- ing Service (ILRS). 1 General Information During the period 2013 January 1 through 2013 December 31, the Simeiz VLBI station participated The Radio Astronomy Laboratory of the Crimean As- in 14 24-hour geodetic sessions. Simeiz regularly trophysical Observatory with its 22-m radio telescope participated in the EUROPE and T2 series of geodetic is located near Simeiz, 25 km to the west of Yalta. The sessions. Simeiz geodynamics area consists of the radio tele- scope RT-22, two satellite laser ranging stations, a per- manent GPS receiver, and a sea level gauge. All these components are located within 3 km (Figure 1). 2.1 Multi-Frequency Molecular Line RT-22, the 22-meter radio telescope, which began Observations operations in 1966, is among the five most efficient telescopes in the world. Various observations in the centimeter and millime- Study of the star-forming regions in molecular lines ter wave ranges are being performed with this tele- started in 1978. Two main types of observation are car- scope now and will be performed in the near future. -

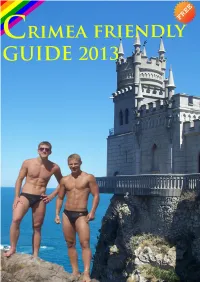

Crimea Guide.Pdf

Crimea Crimean peninsula located on the south of Ukraine, between the Black and Azov Seas. In the southern part of the peninsula located Crimean mountains, more than a kilometer high. Peninsula is connected to the mainland of Ukraine by several isthmuses. The eastern part of Crimea separated from Russia by the narrow Kerch Strait, a width of less then ten kilometers. Crimea - is one of the most interesting places for tourism in Ukraine. On a very small territory - about 26,800 square kilometers, you can find the Sea and the mountains, prairies and lakes, palaces and the ancient city-states, forts and cave cities, beautiful nature and many other interesting places. During two thousand years, the Crimean land often passed from hand to hand. In ancient times, the Greeks colonized Crimea and founded the first cities. After them the Romans came here. After the collapse of the Roman Empire, Crimea became part of the Byzantine Empire. Here was baptized Prince Vladimir who later baptized Kievan Rus. For a long time in the Crimea live together Tatars, Genoese and the small principality Theodoro, but in 1475, Crimea was conquered by the Ottoman Empire. More than three hundreds years the Ottoman Empire ruled the Crimea. After the Russian-Turkish war in 1783, the peninsula became part of the Russian Empire. In 1854-1855 Crimea was occupied forces of Britain, France and Turkey. During the battle near Balaklava death many famous Britons, including Winston Churchill's grandfather. And now, the highest order of the British armed forces - the Victoria Cross minted from metal captured near Balaclava Russian guns. -

Annoucements of Conducting Procurement Procedures

Bulletin No�8(134) February 19, 2013 Annoucements of conducting 002798 Apartments–Maintenance Department of Lviv procurement procedures 3–a Shevchenka St., 79016 Lviv Maksymenko Yurii Ivanovych tel.: (032) 233–05–93 002806 SOE “Makiivvuhillia” Website of the Authorized agency which contains information on procurement: 2 Radianska Sq., 86157 Makiivka, Donetsk Oblast www.tender.me.gov.ua Vasyliev Oleksandr Volodymyrovych Procurement subject: code 35.12.1 – transmission of electricity, 2 lots tel.: (06232) 9–39–98; Supply/execution: at the customer’s address, m/u in the zone of servicing tel./fax: (0623) 22–11–30; of Apartments–Maintenance Department of Lviv; January – December 2013 e–mail: [email protected] Procurement procedure: procurement from the sole participant Website of the Authorized agency which contains information on procurement: Name, location and contact phone number of the participant: lot 1 – PJSC www.tender.me.gov.ua “Lvivoblenergo” Lviv City Power Supply Networks, 3 Kozelnytska St., 79026 Procurement subject: code 71.12.1 – engineering services (development Lviv, tel./fax: (032) 239–20–01; lot 2 – State Territorial Branch Association “Lviv of documentation of reconstruction of technological complex of skip Railway”, 1 Hoholia St., 79007 Lviv, tel./fax: (032) 226–80–45 shaft No.1 of Separated Subdivision “Mine named after V.M.Bazhanov” Offer price: UAH 22015000: lot 1 – UAH 22000000, lot 2 – UAH 15000 (equipment of shaft for works in sump part)) Additional information: Procurement procedure from the sole participant is Supply/execution: Separated Subdivision “Mine named after V.M.Bazhanov” applied in accordance with paragraph 2, part 2, article 39 of the Law on Public of SOE “Makiivvuhillia”; during 2013 Procurement. -

National Report of the Russian Federation

DEPARTMENT OF NAVIGATION AND OCEANOGRAPHY OF THE MINISTRY OF DEFENSE OF THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION NATIONAL REPORT OF THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION 21TH MEETING OF MEDITERRANEAN and BLACKSEAS HYDROGRAPHIC COMMISSION Spain, Cadiz, 11-13 June 2019 1. Hydrographic office In accordance with the legislation of the Russian Federation matters of nautical and hydrographic services for the purpose of aiding navigation in the water areas of the national jurisdiction except the water area of the Northern Sea Route and in the high sea are carried to competence of the Ministry of Defense of the Russian Federation. Planning, management and administration in nautical and hydrographic services for the purpose of aiding navigation in the water areas of the national jurisdiction except the water area of the Northern Sea Route and in the high sea are carried to competence of the Department of Navigation and Oceanography of the Ministry of Defense of the Russian Federation (further in the text - DNO). The DNO is authorized by the Ministry of Defense of the Russian Federation to represent the State in civil law relations arising in the field of nautical and hydrographic services for the purpose of aiding navigation. It is in charge of the Hydrographic office of the Navy – the National Hydrographic office of the Russian Federation. The main activities of the Hydrographic office of the Navy are the following: to carry out the hydrographic surveys adequate to the requirements of safe navigation in the water areas of the national jurisdiction and in the high sea; to prepare -

Tatar Style Guide

Tatar Style Guide Contents What's New? .................................................................................................................................... 4 New Topics ................................................................................................................................... 4 Updated Topics ............................................................................................................................ 4 Introduction ...................................................................................................................................... 5 About This Style Guide ................................................................................................................ 5 Scope of This Document .............................................................................................................. 5 Style Guide Conventions .............................................................................................................. 5 Sample Text ................................................................................................................................. 5 Recommended Reference Material ............................................................................................. 7 Normative References .............................................................................................................. 7 Informative References ............................................................................................................ -

Turkic Toponyms of Eurasia BUDAG BUDAGOV

BUDAG BUDAGOV Turkic Toponyms of Eurasia BUDAG BUDAGOV Turkic Toponyms of Eurasia © “Elm” Publishing House, 1997 Sponsored by VELIYEV RUSTAM SALEH oglu T ranslated by ZAHID MAHAMMAD oglu AHMADOV Edited by FARHAD MAHAMMAD oglu MUSTAFAYEV Budagov B.A. Turkic Toponyms of Eurasia. - Baku “Elm”, 1997, -1 7 4 p. ISBN 5-8066-0757-7 The geographical toponyms preserved in the immense territories of Turkic nations are considered in this work. The author speaks about the parallels, twins of Azerbaijani toponyms distributed in Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, Altay, the Ural, Western Si beria, Armenia, Iran, Turkey, the Crimea, Chinese Turkistan, etc. Be sides, the geographical names concerned to other Turkic language nations are elucidated in this book. 4602000000-533 В ------------------------- 655(07)-97 © “Elm” Publishing House, 1997 A NOTED SCIENTIST Budag Abdulali oglu Budagov was bom in 1928 at the village o f Chobankere, Zangibasar district (now Masis), Armenia. He graduated from the Yerevan Pedagogical School in 1947, the Azerbaijan State Pedagogical Institute (Baku) in 1951. In 1955 he was awarded his candidate and in 1967 doctor’s degree. In 1976 he was elected the corresponding-member and in 1989 full-member o f the Azerbaijan Academy o f Sciences. Budag Abdulali oglu is the author o f more than 500 scientific articles and 30 books. Researches on a number o f problems o f the geographical science such as geomorphology, toponymies, history o f geography, school geography, conservation o f nature, ecology have been carried out by academician B.A.Budagov. He makes a valuable contribution for popularization o f science. -

Travel Guide

TRAVEL GUIDE Traces of the COLD WAR PERIOD The Countries around THE BALTIC SEA Johannes Bach Rasmussen 1 Traces of the Cold War Period: Military Installations and Towns, Prisons, Partisan Bunkers Travel Guide. Traces of the Cold War Period The Countries around the Baltic Sea TemaNord 2010:574 © Nordic Council of Ministers, Copenhagen 2010 ISBN 978-92-893-2121-1 Print: Arco Grafisk A/S, Skive Layout: Eva Ahnoff, Morten Kjærgaard Maps and drawings: Arne Erik Larsen Copies: 1500 Printed on environmentally friendly paper. This publication can be ordered on www.norden.org/order. Other Nordic publications are available at www.norden.org/ publications Printed in Denmark T R 8 Y 1 K 6 S 1- AG NR. 54 The book is produced in cooperation between Øhavsmuseet and The Baltic Initiative and Network. Øhavsmuseet (The Archipelago Museum) Department Langelands Museum Jens Winthers Vej 12, 5900 Rudkøbing, Denmark. Phone: +45 63 51 63 00 E-mail: [email protected] The Baltic Initiative and Network Att. Johannes Bach Rasmussen Møllegade 20, 2200 Copenhagen N, Denmark. Phone: +45 35 36 05 59. Mobile: +45 30 25 05 59 E-mail: [email protected] Top: The Museum of the Barricades of 1991, Riga, Latvia. From the Days of the Barricades in 1991 when people in the newly independent country tried to defend key institutions from attack from Soviet military and security forces. Middle: The Anna Akhmatova Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia. Handwritten bark book with Akhmatova’s lyrics. Made by a GULAG prisoner, wife of an executed “enemy of the people”. Bottom: The Museum of Genocide Victims, Vilnius, Lithuania. -

The Concept of Traditional Islam

In recent years, the concept of traditional Islam has attracted attention of researchers both in Russia and beyond. A serious drawback of some of the works is excessive politicization of Renat Bekkin Renat acquaintance with sources both in the languages of the so-called discourse, as well as that authors seem to have only superficial problem is inherent mainly in the works of Russian authors, the Muslim peoples of Russia and in Russian language. The first by Edited second one in publications by authors from the West. * * * Structurally, the book has two parts: a theoretical part Traditional Islam: the concept and its interpretations and a practical one Traditional Islam in the Russian regions and Crimea. * * * All the articles in the book include some consideration of the The Concept of the state to designate their preferred model of state-confessional traditional Islam concept as an artificial construct promoted by relations, in which religious organisations and individual believers demonstrate their loyalty to the political regime. Organisations Traditional Islam and believers who criticize the state’s domestic and foreign policy can then be described by the authorities and the muftiates to be in Modern Islamic Discourse in Russia representatives of ‘non-traditional Islam’. Edited by The Concept of Traditional Islam in Modern Islamic Discourse Russia Renat Bekkin ISBN 978-9926-471-21-7 THE CONCEPT OF TRADITIONAL ISLAM IN MODERN ISLAMIC DISCOURSE IN RUSSIA The Concept of Traditional Islam in Modern Islamic Discourse in Russia Edited by Renat Bekkin Copyright © 2020 Center for Advanced Studies This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exceptions and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of the Center for Advanced Studies.