The Founding Years; 2014-03-31

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bob Pease, Analog Guru, Died 5 Years Ago - Media Rako.Com/Media 1 of 12

Bob Pease, analog guru, died 5 years ago - Media Rako.com/Media 1 of 12 Rako Studios » Media » Tech » Electronics » Bob Pease, analog guru, died 5 years ago Bob Pease, analog guru, died 5 years ago Bob Pease was a true standout, the gentleman genius. Notorious analog engineer Bob Pease died five Saturday, Bob had come to the service from years ago, on June 18, 2011. His passing was his office at National Semiconductor, now all the more tragic since he died driving home Texas Instruments. My buddy has a from a remembrance for fellow analog saying, "Everyone wants to be somebody, no great Jim Williams. Although it was a one wants to become somebody." 1 of 12 9/2/2018 6:49 PM 1 of 12 Bob Pease, analog guru, died 5 years ago - Media Rako.com/Media 2 of 12 Bob's being the most famous analog designer After coming to National Semi, Bob learned was the result of his hard work becoming a analog IC design, back in the days ofhand-cut brilliant engineer, with a passion for helping Rubylith masks. There was no Spice simulator others. Fran Hoffart, retired Linear Tech apps back then, and Pease had deep ridicule for engineer and former colleague recalls, "Citing a engineers that relied on computer simulations, need for educating fellow engineers in the insteadof thinking through the problem and design of bandgap references, Bob anointed making some quickback-of-envelope himself 'The Czar of Bandgaps,' complete with calculations. He accepted that Spice was useful a quasi-military suit with a sword and a especially for inexperienced engineers, but was necklace made from metal TO-3 packages." He concerned thatengineers were substituting would help any engineer with a problem, even computer smarts for real smarts. -

Analog Father.Indd

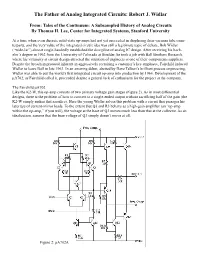

The Father of Analog Integrated Circuits: Robert J. Widlar From: Tales of the Continuum: A Subsampled History of Analog Circuits By Thomas H. Lee, Center for Integrated Systems, Stanford University At a time when even discrete solid-state op-amps had not yet succeeded in displacing their vacuum tube coun- terparts, and the very value of the integrated circuit idea was still a legitimate topic of debate, Bob Widlar (“wide-lar”) almost single-handedly established the discipline of analog IC design. After receiving his bach- elor’s degree in 1962 from the University of Colorado at Boulder, he took a job with Ball Brothers Research, where his virtuosity at circuit design attracted the attention of engineers at one of their components suppliers. Despite the breach in protocol inherent in aggressively recruiting a customer’s key employee, Fairchild induced Widlar to leave Ball in late 1963. In an amazing debut, abetted by Dave Talbert’s brilliant process engineering, Widlar was able to put the world’s first integrated circuit op-amp into production by 1964. Development of the μA702, as Fairchild called it, proceeded despite a general lack of enthusiasm for the project at the company. The Fairchild μA702 Like the K2-W, this op-amp consists of two primary voltage gain stages (Figure 2). As in most differential designs, there is the problem of how to convert to a single-ended output without sacrificing half of the gain (the K2-W simply makes that sacrifice). Here the young Widlar solves this problem with a circuit that presages his later use of current-mirror loads. -

Analog Aficionados Party 2014 - Media Rako.Com/Media 1 of 13

Analog aficionados party 2014 - Media Rako.com/Media 1 of 13 Rako Studios » Media » Tech » Electronics » Analog aficionados party 2014 Analog aficionados party 2014 The 2014 Analog Aficionados party is Sunday, February 9, 2014. From 5:00 to 9:00PM. It is at David's Restaurant in Santa Clara near Phil Sittner and IC designer Barry Harvey talk the golf course. Over 150 people made last tech under the watchful eye of Atmel year's party. This is the fifth annual party. marketing director Donna Castillo. It is too late to sign up for the party. If you show up we can print a Atmel's marketing department designed new badge on the spot. logos, badges, and the placemat for the Analog Aficionados party. You can see the placemats on the table, along with the stylish new badge design Barry is wearing. 1 of 13 9/30/2018 5:13 PM 1 of 13 Analog aficionados party 2014 - Media Rako.com/Media 2 of 13 And do come for the food. We will have beef and lamb carvings, vegetarian, vegan and soft drinks. Thanks to long-time sponsor Linear Systems continuing their support, and previous sponsor UBM doubling last year's contribution, and now Atmel being even more generous this year, our food budget has more than doubled. Unlike last year where I tried to bring the food out in batches, we will bring it all out at 6:00. Well not all, the chocolate-covered strawberries will be after you have devoured all the entrees. This is not a sit-down affair, we want you to mingle and grab food and drink from all around . -

IC Op-Amps Through the Ages

Handout #15: EE214 Fall 2003 IC Op-Amps Through the Ages 1.0 Introduction The operational amplifier concept emerged from extensive development of electronic ana- log computers in the 1940s. Operational amplifiers get their name from their ability to per- form mathematical operations such as summation, integration and differentiation. With the addition of logarithmic amplifiers and feedback, one may perform multiplication and division as well. These abilities allow op-amp circuits to simulate differential equations, such as those describing the trajectory of an aircraft, for example. Countless analog com- puters were used throughout the second world war to produce “smarter” weapons capable of predicting where a target would be some time in the future, to determine the optimal fir- ing conditions to ensure with high probability that a shell would intercept it then. The abil- ity to “program” an analog computer rapidly by changing amplifier gains and connectivity made it an indispensable tool for both weaponry and academic research. Mechanical ana- log computers had preceded electronic ones, and changing gears and linkages made repro- gramming a cumbersome affair. The desire for compactness and universality led to the development of general-purpose high gain blocks intended for use within a feedback loop, the op-amp idea that is “obvi- ous” today. Perhaps the most famous op-amp of the vacuum tube era was the Philbrick K2-W, whose particularly elegant design served as the inspiration for transistorized coun- terparts throughout the 1950s and 1960s. Early efforts at integrated circuit op-amps attempted to replicate on a one-to-one basis the connectivity of earlier discrete designs. -

Bob Pease Lab Notes Part 9.Pdf

934 PROCEEDINGS OF THE IEEE, VOL. 68, NO. 7, JULY 1980 A test circuit of Fig. 1 was constructed using standard 741 type OA’s, monolithic transistorarrays and 0.1 percent resistors. Initially,with i = 0, the mirror gains were equalized by removing R1 and R4 (thus assuring I+ = I-) ad adjusting R 5 to obtain io = 0. For VCCS opera- tion, G, was measured leaving port B-E’ open (i = 0), while for CCCS operation, port A-A’ was shorted to ground making u1 = u2 = 0. To minimize scaling errordue to frnite gain Aof the OA’s, theratio (Rz + R3)/R1 was restricted to a maximum value of 100. ForA - lo5, this assures less than 0.1 percent error at dc due to finite OA gain. Using various resistance combinations, values of G, up to 0.5 mho and Ai as large as 400 were obtained with a scaling error of the order of 1 percent, which was largely due to nonunity gain of the mirrors. Indivi- dual trimmingof the mirrors to precisely unity gain (tO.1 percent) Fig. 1. Oscillator network in the above letter tuned for an oscillation resulted in scaling errorsof the orderof resistance tolerances. The frequency of 10 Hz. (x-axis; 50 ms/cm; y-axis: 2 V/cm) small signal performance of the convertor is shown in Fig. 2(a) for the case where R1 = - and Rz = R3 = 0. Here the circuit is a VCCS with G, = (l/R4). For large R4 the bandwidth is equal to the GBW of the the input of the next “G” block, will cause phase errors, causing the OA’s (-1 MHz). -

Fairchild Semiconductor

Report to the Computer History Museum on the Information Technology Corporate Histories Project Semiconductor Sector Fairchild Semiconductor Company Details Name: Fairchild Semiconductor Sector: Semiconductor Sector Description . THIS SITE WAS ESTABLISHED TO COLLECT AND PRESENT INFORMATION AND STORIES RELATED TO FAIRCHILD SEMICONDUCTOR AS PART OF THE OCTOBER 2007 CELEBRATION OF THE FIFTIETH ANNIVERSARY OF THE FOUNDING OF THE COMPANY. IF YOU HAVE ANY CORRECTIONS OR ADDITIONAL INFORMATION TO CONTRIBUTE PLEASE CONTACT THE FACILITATORS LISTED BELOW. Overview Founded in 1957 in a building now designated as California Historical Landmark # 1000 in Palo Alto, California by eight young engineers and scientists from Shockley Semiconductor Laboratories, Fairchild Semiconductor Corporation pioneered new products and technologies together with an entrepreneurial style and manufacturing and marketing techniques that reshaped Silicon Valley and the world-wide industry. The Planar process invented in 1959 revolutionized the production of semiconductor devices and enables the manufacture of today's billion transistor microprocessor and memory chips. Funded by and later acquired as a division of Fairchild Camera and Instrument Corporation of Syosset, New York, Fairchild was the first manufacturer to introduce high-frequency silicon transistors and practical monolithic integrated circuits to the market. At the peak of its influence in the mid-1960s, the division was one of the world’s largest producers of silicon transistors and controlled over 30 percent of the market for ICs. Director of Research and Development, Gordon Moore observed in 1965 that device complexity was increasing at a consistent rate and predicted that this would continue into the future. “Moore’s Law,” as it became known, created a yardstick against which companies have measured their technology progress for over 40 years. -

Bob Pease on Analog Vol

$59.00 LIBRARY FOCUS ON: BOB PEASE ON ANALOG VOL. 2 A compendium of technical articles from legendary Electronic Design engineer Bob Pease Copyright © 2016 by Penton Media, Inc. All rights reserved. SUBSCRIBE: electronicdesign.com/subscribe | 1 ELECTRONIC DESIGN LIBRARY FOCUS ON: BOB PEASE ON ANALOG, PART 2 CONTENTS 2 | Welcome 3 | What’s All This Battery-Powered Stuff, Anyhow? 10 | What’s All This Battery-Charging Stuff, Anyhow? 19 | What’s all this Soakage Stuff, Anyhow? 26 | What’s All This Future Stuff, Anyhow? 29 | What’s All This Ripple Rejection Stuff, Anyhow? (Part 1) 32 | What’s All This Ripple Rejection Stuff, Anyhow? (Part 2) 35 | What’s All This One-Transistor Op-Amp Stuff, Anyhow? 38 | What’s All This Bridge Amplifier Stuff, Anyhow? 41 | What’s All This Best Amplifier Stuff, Anyhow? 44 | What’s All This Profit Stuff, Anyhow? 51 | More Resources From Electronic Design electronicdesign.com ☞REGISTER: electronicdesign.com | 1 SUBSCRIBE: electronicdesign.com/subscribe | 1 ELECTRONIC DESIGN LIBRARY FOCUS ON: BOB PEASE ON ANALOG EDITORIAL Welcome to the second volume in our Bob Pease e-book series. WE ALL REMEMBER BOB PEASE FONDLY—for his analog design expertise as well as his sense of humor. Just some months ago, someone in the industry who worked with Bob talked about how he would always say that an engineer’s most valuable tool was a solder- ing iron. We were lucky he shared his wit and knowledge with us for years with his special column for Electronic Design, “Pease Porridge.” In this second Pease e-book, we’ve gathered some columns on topics ranging from battery power and charging to soakage. -

14 Exploring and Explaining Circuits by Yannis Tsividis Recollections from Yannis’ Graduate Student Years at Berkeley by Paul Gray

FALL 2014 VOL. 6 • NO. 4 www.ieee.org/sscs-news FEATURES 14 Exploring and Explaining Circuits By Yannis Tsividis Recollections from Yannis’ Graduate Student Years at Berkeley By Paul Gray 36 Yannis Tsividis’ Early Contributions to MOS Filters By John Khoury and Mihai Banu ABOUT THIS IMAGE: Columbia’s mixed-signal group in the late 1980s. Find out 41 A Mind for all Seasons who’s who in “Exploring and Explaining Circuits.” By Nagendra Krishnapura and Shanthi Pavan 44 How a Humble Circuit Designer Revolutionized MOS Transistor Modeling By Colin C. McAndrew COLUMNS/ DEPARTMENTS 48 Yannis Tsividis, Path-Breaking Researcher and Educator 3 CONTRIBUTORS By Gabor Temes 4 EDITOR’S NOTE 5 ASSOCIATE EDITOR’S VIEW 52 Yannis Tsividis, Educator 6 cONTRIBUTING EDITOR’s VIEW By David Vallancourt 7 cIRCUIT INTUITIONS Yannis Tsividis as a Role Model 9 A CIRCUIT FOR ALL SeASONS for Reversing the Negative Spiral 13 GUEST EDITORIAL of Basic Circuits and Systems Education 63 PEOPLE By Joos Vandewalle 66 CONFERENce REPORTS 68 CHAPTERS 76 IEEE NEWS 79 CONFERENce CALENDAR TUTORIAL 56 Telemetry for Implantable Medical Devices By Ulrich Bihr, Tianyi Liu, and Maurits Ortmanns Digital Object Identifier 10.1109/MSSC.2014.2347712 IEEE SOLID-STATE CIRCUITS MAGAZINE FALL 2014 1 Senior Administrator, Katherine Olstein Terms to 31 Dec. 2015 IEEE SSCS, 445 Hoes Lane Arya Behzad, Shekhar Borkar, Michael H. IEEE SOLID-STATE Piscataway, NJ 08854 USA Perrott, Trudy Stetzler, William Redman-White CIRCUITS MAGAZINE Tel: +1 732 981 3410 Fax: +1 732 981 3401 Terms to 31 Dec. 2016 EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Jake Baker, Franz Dielacher, Peter Kinget, Mary Y. -

Battery Life and How to Improve It

Battery Life and How To Improve It Battery and Energy Technologies Technologies Battery Life (and Death) Low Power Cells High Power Cells For product designers, an understanding of the factors affecting battery life is vitally important for managing both product Chargers & Charging performance and warranty liabilities particularly with high cost, high power batteries. Offer too low a warranty period and you won't Battery Management sell any batteries/products. Overestimate the battery lifetime and you could lose a fortune. Battery Testing Cell Chemistries FAQ That batteries have a finite life is due to occurrence of the unwanted chemical or physical changes to, or the loss of, the active materials of which Free Report they are made. Otherwise they would last indefinitely. These changes are usually irreversible and they affect the electrical performance of the cell. Buying Batteries in China Battery life can usually only be extended by preventing or reducing the cause of the unwanted parasitic chemical effects which occur in the cells. Choosing a Battery Some ways of improving battery life and hence reliability are considered below. How to Specify Batteries Battery cycle life is defined as the number of complete charge - discharge cycles a battery can perform before its nominal capacity falls below Sponsors 80% of its initial rated capacity. Lifetimes of 500 to 1200 cycles are typical. The actual ageing process results in a gradual reduction in capacity over time. When a cell reaches its specified lifetime it does not stop working suddenly. The ageing process continues at the same rate as before so that a cell whose capacity had fallen to 80% after 1000 cycles will probably continue working to perhaps 2000 cycles when its effective capacity will have fallen to 60% of its original capacity. -

What Exactly Is an Operational Amplifier? Let's Define What That Component Is and Look at the Parameters of This Amazing Device

741 Op-Amp Tutorial, op-amps, Operational Amplifier Page 1 of 14 © by Tony van Roon What exactly is an OPerational AMPlifier? Let's define what that component is and look at the parameters of this amazing device. An operational amplifier IC is a solid-state integrated circuit that uses external feedback to control its functions. It is one of the most versatile devices in all of electronics. The term 'op-amp' was originally used to describe a chain of high performance dc amplifiers that was used as a basis for the analog type computers of long ago. The very high gain op-amp IC's our days uses external feedback networks to control responses. The op-amp without any external devices is called 'open-loop' mode, referring actually to the so-called 'ideal' operational amplifier with infinite open-loop gain, input resistance, bandwidth and a zero output resistance. However, in practice no op-amp can meet these ideal characteristics. And as you will see, a little later on, there is no such thing as an ideal op-amp. Since the LM741/NE741/uA741 Op-Amps are the most popular one, this tutorial is direct associated with this particular type. Nowadays the 741 is a frequency compensated device and although still widely used, the Bi-polar types are low-noise and replacing the old-style op-amps. Let's go back in time a bit and see how this device was developed. The term "operational amplifier" goes all the way back to about 1943 where this name was mentioned in a paper written by John R. -

Performance Characteristics and Design of Voltage References Yunting Yin Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Graduate Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2017 Performance characteristics and design of voltage references Yunting Yin Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd Part of the Electrical and Electronics Commons Recommended Citation Yin, Yunting, "Performance characteristics and design of voltage references" (2017). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 17370. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd/17370 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Performance characteristics and design of voltage references by Yunting Yin A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Major: Electrical Engineering Program of Study Committee: Randall L. Geiger, Major Professor Degang J. Chen Yong Guan Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2017 Copyright ©Yunting Yin, 2017. All rights reserved. ii DEDICATION To my family iii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES ................................................................................................................... v LIST OF TABLES .................................................................................................................. -

Oral History of Brian Hollins

Oral History of Brian Hollins Interviewed by: David Laws Recorded: November 4, 2014 Mountain View, California CHM Reference number: X7284.2015 © 2014 Computer History Museum Oral History of Brian Hollins David Laws: Today is November the fourth, 2014. We're at the Computer History Museum in Mountain View, California. I'm David Laws, semiconductor curator at the museum. Today, we're going to record an oral history with Brian Hollins. Brian spent many years in Silicon Valley on the manufacturing side of the semiconductor industry. I'd like to get insight into different aspects of his background and collect information on the state of the industry at various points in his career. So welcome, Brian. Thank you for joining us to today. Brian Hollins: My pleasure. Laws: Perhaps we could start out with a little bit about your background, your family. Where were you born? What were the major influences on your choice of career? Hollins: I'm originally from Britain. I was brought up in Liverpool from a very early age. That's a northwest city, which was made famous a few years later by four certain musicians. I went to school in Liverpool, and I went to a secondary technical school, which did all of the usual subjects-- math, history, English, geography, et cetera. But it also included some artisan-type courses, like woodwork, metalwork, engineering drawing, that kind of thing. And I actually found that I enjoy that. They were very hands on. In woodwork, for example, we would learn how to make dovetail joints. And in metalwork, we would weld things together.