History of Semiconductor Engineering Bo Lojek

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Report to the Board of Governors Front & Back Cover Story

March 2017 Report to the Board of Governors Front & Back cover story Trades Throwdown: Skills Canada BC competition hosted by KPU Cloverdale, B.C. – Fire runs in the veins of third generation hone their skills, but also meet and compete with other future welder Jaeden Wildenboer. leaders and fellow entrepreneurs in their respective An apprentice welder and graduate from Kwantlen Polytechnic industries.” University (KPU) through the Youth TRAIN in Trades program In addition to welding, students from the Surrey and Delta (former ACE IT program), Wildenboer is back to defend his school districts will have the chance to show off their skills in regional title at Skills Canada BC regional competition for the architecture, automotive service, carpentry, fashion Lower Fraser Valley region this Friday at KPU’s Tech campus in technology, mechanics and plumbing. All trades for which Cloverdale. training and certification are available for at KPU. “Both my dad and late grandfather got me interested in trades KPU faculty will be directly involved, volunteering their time as and they are both tradesmen,” said Wildenboer. Skills Canada judges for several of the competitions at the regional, “really puts you to the test to see what you can achieve. It provincial and international levels. helped push me in the direction of going to KPU and becoming The competition kicks off at 8 a.m. and runs until 2 p.m. on a welder.” Friday, Feb. 24 at KPU Tech (5500 180 St, Surrey). The KPU Wildenboer and a slew of other trades students from the Richmond campus (8771 Lansdowne Rd, Richmond) is also Lower Fraser Valley will gather at KPU’s Tech campus this hosting Skills Canada BC for the Central Lower Mainland Friday to throwdown in the first of several regional students on March 2. -

Semiconductor Industry Social Media Review

Revealed SOCIAL SUCCESS White Paper Who’s winning the social media battle in the semiconductor industry? Issue 2, September 3, 2014 The contents of this White Paper are protected by copyright and must not be reproduced without permission © 2014 Publitek Ltd. All rights reserved Who’s winning the social media battle in the semiconductor industry? Issue 2 SOCIAL SUCCESS Who’s winning the social media battle in the semiconductor industry? Report title OVERVIEW This time, in the interest of We’ve combined quantitative balance, we have decided to and qualitative measures to This report is an update to our include these companies - Intel, reach a ranking for each original white paper from channel. Cross-channel ranking Samsung, Sony, Toshiba, Nvidia led us to the overall index. September 2013. - as well as others, to again analyse the following channels: As before, we took a company’s Last time, we took the top individual “number semiconductor companies 1. Blogs score” (quantitative measure) (according to gross turnover - 2. Facebook for a channel, and multiplied main source: Wikipedia), of this by its “good practice score” 3. Google+ which five were ruled out due (qualitative measure). 4. LinkedIn to the diversity of their offering 5. Twitter The companies were ranked by and the difficulty of segmenting performance in each channel. 6. YouTube activity relating to An average was then taken of semiconductors. ! their positions in each to create the final table. !2 Who’s winning the social media battle in the semiconductor industry? Issue 2 Due to the instantaneous nature of social media, this time we decided to analyse a narrower time frame, and picked a single month - August 2014. -

Bob Pease, Analog Guru, Died 5 Years Ago - Media Rako.Com/Media 1 of 12

Bob Pease, analog guru, died 5 years ago - Media Rako.com/Media 1 of 12 Rako Studios » Media » Tech » Electronics » Bob Pease, analog guru, died 5 years ago Bob Pease, analog guru, died 5 years ago Bob Pease was a true standout, the gentleman genius. Notorious analog engineer Bob Pease died five Saturday, Bob had come to the service from years ago, on June 18, 2011. His passing was his office at National Semiconductor, now all the more tragic since he died driving home Texas Instruments. My buddy has a from a remembrance for fellow analog saying, "Everyone wants to be somebody, no great Jim Williams. Although it was a one wants to become somebody." 1 of 12 9/2/2018 6:49 PM 1 of 12 Bob Pease, analog guru, died 5 years ago - Media Rako.com/Media 2 of 12 Bob's being the most famous analog designer After coming to National Semi, Bob learned was the result of his hard work becoming a analog IC design, back in the days ofhand-cut brilliant engineer, with a passion for helping Rubylith masks. There was no Spice simulator others. Fran Hoffart, retired Linear Tech apps back then, and Pease had deep ridicule for engineer and former colleague recalls, "Citing a engineers that relied on computer simulations, need for educating fellow engineers in the insteadof thinking through the problem and design of bandgap references, Bob anointed making some quickback-of-envelope himself 'The Czar of Bandgaps,' complete with calculations. He accepted that Spice was useful a quasi-military suit with a sword and a especially for inexperienced engineers, but was necklace made from metal TO-3 packages." He concerned thatengineers were substituting would help any engineer with a problem, even computer smarts for real smarts. -

Chapter1: Semiconductor Diode

Chapter1: Semiconductor Diode. Electronics I Discussion Eng.Abdo Salah Theoretical Background: • The semiconductor diode is formed by doping P-type impurity in one side and N-type of impurity in another side of the semiconductor crystal forming a p-n junction as shown in the following figure. At the junction initially free charge carriers from both side recombine forming negatively c harged ions in P side of junction(an atom in P -side accept electron and be comes negatively c harged ion) and po sitive ly c harged ion on n side (an atom in n-side accepts hole i.e. donates electron and becomes positively charged ion)region. This region deplete of any type of free charge carrier is called as depletion region. Further recombination of free carrier on both side is prevented because of the depletion voltage generated due to charge carriers kept at distance by depletion (acts as a sort of insulation) layer as shown dotted in the above figure. Working principle: When voltage is not app lied acros s the diode , de pletion region for ms as shown in the above figure. When the voltage is applied be tween the two terminals of the diode (anode and cathode) two possibilities arises depending o n polarity of DC supply. [1] Forward-Bias Condition: When the +Ve terminal of the battery is connected to P-type material & -Ve terminal to N-type terminal as shown in the circuit diagram, the diode is said to be forward biased. The application of forward bias voltage will force electrons in N-type and holes in P -type material to recombine with the ions near boundary and to flow crossing junction. -

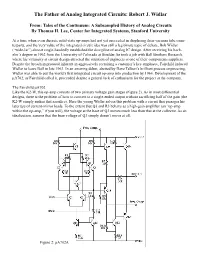

Analog Father.Indd

The Father of Analog Integrated Circuits: Robert J. Widlar From: Tales of the Continuum: A Subsampled History of Analog Circuits By Thomas H. Lee, Center for Integrated Systems, Stanford University At a time when even discrete solid-state op-amps had not yet succeeded in displacing their vacuum tube coun- terparts, and the very value of the integrated circuit idea was still a legitimate topic of debate, Bob Widlar (“wide-lar”) almost single-handedly established the discipline of analog IC design. After receiving his bach- elor’s degree in 1962 from the University of Colorado at Boulder, he took a job with Ball Brothers Research, where his virtuosity at circuit design attracted the attention of engineers at one of their components suppliers. Despite the breach in protocol inherent in aggressively recruiting a customer’s key employee, Fairchild induced Widlar to leave Ball in late 1963. In an amazing debut, abetted by Dave Talbert’s brilliant process engineering, Widlar was able to put the world’s first integrated circuit op-amp into production by 1964. Development of the μA702, as Fairchild called it, proceeded despite a general lack of enthusiasm for the project at the company. The Fairchild μA702 Like the K2-W, this op-amp consists of two primary voltage gain stages (Figure 2). As in most differential designs, there is the problem of how to convert to a single-ended output without sacrificing half of the gain (the K2-W simply makes that sacrifice). Here the young Widlar solves this problem with a circuit that presages his later use of current-mirror loads. -

Timeline of the Semiconductor Industry in South Portland

Timeline of the Semiconductor Industry in South Portland Note: Thank you to Kathy DiPhilippo, Executive Director/Curator of the South Portland Historical Society and Judith Borelli, Governmental Relations of Texas Inc. for providing some of the information for this timeline below. Fairchild Semiconductor 1962 Fairchild Semiconductor (a subsidiary of Fairchild Camera and Instrument Corp.) opened in the former Boland's auto building (present day Back in Motion) at 185 Ocean Street in June of 1962. They were there only temporarily, as the Western Avenue building was still being constructed. 1963 Fairchild Semiconductor moves to Western Avenue in February 1963. 1979 Fairchild Camera and Instrument Corp. is acquired/merged with Schlumberger, Ltd. (New York) for $363 million. 1987 Schlumberger, Ltd. sells its Fairchild Semiconductor Corp. subsidiary to National Semiconductor Corp. for $122 million. 1997 National Semiconductor sells the majority ownership interest in Fairchild Semiconductor to an investment group (made up of Fairchild managers, including Kirk Pond, and Citcorp Venture Capital Ltd.) for $550 million. Added Corporate Campus on Running Hill Road. 1999 In an initial public offering in August 1999, Fairchild Semiconductor International, Inc. becomes a publicly traded corporation on the New York Stock Exchange. 2016 Fairchild Semiconductor International, Inc. is acquired by ON Semiconductor for $2.4 billion. National Semiconductor 1987 National Semiconductor acquires Fairchild Semiconductor Corp. from Schlumberger, Ltd. for $122 million. 1995 National Semiconductor breaks ground on new 200mm factory in December 1995. 1996 National Semiconductor announces plans for a $600 million expansion of its facilities in South Portland; construction of a new wafer fabrication plant begins. 1997 Plant construction for 200mm factory completed and production starts. -

Mos Technology, 1963-1974: a Dozen Crucial Years

One of IBM’s most important MOS Technology, 1963-1974: A Dozen Crucial Years contributions to MOS research came from the Components Division, which was responsible for developing by Ross Knox Bassett and manufacturing bipolar transistors for its large computer systems and had very little interest in MOS transistors line can be drawn from the as such. As part of its work on Frosch’s and Derick’s work on bipolar transistors, Donald Kerr and silicon dioxide to the MOS (metal- a group of engineers had discovered A that depositing small amounts of oxide-semiconductor) transistor’s domi- nance of semiconductor technology, phosphorous on the silicon-dioxide but it is neither short nor straight. That surface and forming a layer of line has several discernable segments, phosphosilicate glass (PSG) could first from Frosch and Derick’s work, limit the amount of leakage in bipolar until 1963. In this interval, by and transistors and play an important role large, no one thought seriously about a in enhancing the stability of MOS metal-oxide-semiconductor as a viable transistors. Jerome Eldridge and Pieter technology in its own right. The second Balk from IBM Research implemented segment runs from 1963, when the this work by using thin layers of combination of integrated circuits and PSG to make stable MOS devices. the planar manufacturing process had Other important work on the physics FIG. 2. Drawing of Atalla and Kahng’s “silicon-silicon dioxide surface device,” now known as and chemistry of MOS devices done led people to see MOS transistors as a the MOS transistor, from a 1961 Bell Labs technical memorandum by Kahng. -

Readingsample

Springer Series in Materials Science 106 Into The Nano Era Moore's Law Beyond Planar Silicon CMOS Bearbeitet von Howard Huff 1. Auflage 2008. Buch. xxviii, 348 S. Hardcover ISBN 978 3 540 74558 7 Format (B x L): 15,5 x 23,5 cm Gewicht: 725 g Weitere Fachgebiete > Technik > Elektronik > Mikroprozessoren Zu Inhaltsverzeichnis schnell und portofrei erhältlich bei Die Online-Fachbuchhandlung beck-shop.de ist spezialisiert auf Fachbücher, insbesondere Recht, Steuern und Wirtschaft. Im Sortiment finden Sie alle Medien (Bücher, Zeitschriften, CDs, eBooks, etc.) aller Verlage. Ergänzt wird das Programm durch Services wie Neuerscheinungsdienst oder Zusammenstellungen von Büchern zu Sonderpreisen. Der Shop führt mehr als 8 Millionen Produkte. 2 The Economic Implications of Moore’s Law G.D. Hutcheson 2.1 Introduction One hundred nanometers is a fundamental technology landmark. It is the demarca- tion point between microtechnology and nanotechnology. The semiconductor indus- try crossed it just after the second millennium had finished. In less than 50 years, it had come from transistors made in mils (one-thousandth of an inch or 25.4 mi- crons); to integrated circuits which were popularized as microchips; and then as the third millennium dawned, nanochips. At this writing, nanochips are the largest single sector of nanotechnology. This, in spite of many a nanotechnology expert’s predic- tion that semiconductors would be dispatched to the dustbin of science – where tubes and core memory lie long dead. Classical nanotechnologists should not feel any dis- grace, as pundits making bad predictions about the end of technology progression go back to the 1960s. Indeed, even Gordon Moore wondered as he wrote his clas- sic paper in 1965 if his observation would hold into the 1970s. -

Chance Canadian Tire Jumpstart Charities Annual Report 2012

GIVING KIDS A SP RTING CHANCE canadian tire jumpstart charities annual report 2012 630737_Jumpstart_Repro_E_R1.indd 1 13-05-01 11:10 AM Welcome jumpstart annual report 2012 WE OWE IT ALL TO YOU 2012 Was a year of both change and remarkable groWth. We accomplished our best year to date, and we want to thank our loyal supporters. Together, with the Canadian Tire Family of Companies along with our valued customers, vendors and donors, Jumpstart invested more than $12 million into Canadian communities to help kids who otherwise could not have participated in sports and recreational activities. Along with the support of our dedicated network of 332 chapters and more than 2,500 community partners coast to coast, Jumpstart enriched the lives of 125,372 kids this year alone. Thanks to you, we have given our children more than just the freedom of play; we have given them the chance to learn life skills, create memories and develop lasting friendships. We accomplished a number of initiatives in 2012 which have garnered support and recognition while raising more money than ever. Jumpstart Pedal for Kids brought together cycling enthusiasts from Canadian Tire Retail, FGL Sports, Mark’s, Financial Services, Jumpstart as well as friends from outside the enterprise to bike 500 kilometres from Kingston to Niagara Falls, Ontario. In Welland, Ontario, children will be able to play baseball at the new Canadian Tire Jumpstart–Billes Family Field. The Port aux Basques, Newfoundland, local Canadian Tire Dealer and his staff won a Jumpstart national in-store Red Ball contest to bring Stanley Cup champion and Olympic gold medallist Jonathan Toews to the community for the thrill of a lifetime. -

M Ike G Runtm An, B Lazing the T Rail. T He E Arly H Istory of Spacecraft And

Mike Gruntman, Blazing the Trail. The Early History of Spacecraft and Rocketry, AIAA, 2004, pp. 231-234 eral Schriever at 409 East Manchester Blvd., Inglewood, Califor Inglewood, Blvd., Manchester East 409 at Schriever eral DevelopmentDivision Western special the program, Atlas the manage To followed. effort development Force Air the of reorganization the First, program. ICBM American the accelerated cantly now possiblewithin high-yield, compact, and low-weight nuclear warheads: the Atlas development on 1 March 1954, the Bravo test demonstrated the feasibility of what relaxed and the program priority and funding increased. In the early an 1960s providing the stringent assuring performance characteristics were some- in status operational the achieve could Atlas the that stated Augenstein W. Bruno RAND's by assessment The ICBM. Atlas the of feasibility the confirmed study dent mental andresearch theexperi- analyses, supervisingtheresearchphase,andcompletelycontrolling system making of capable engineers and scientists of group competent unusually cal direction be in the hands of techni- over-all that requires agency “the nature of the task for this new future. The Committee stated that would become prominent in the ing andtechnicaldirection area, technical new a of emergence demanding thus was ICBM the of complexity The urgent. Atlas program was deemed most management agency for the entire Setting up a special development- begin. would development actual the a top priority of the Air Force and rank now would km), (10,200 miles n 5500 of -

Microprocessors in the 1970'S

Part II 1970's -- The Altair/Apple Era. 3/1 3/2 Part II 1970’s -- The Altair/Apple era Figure 3.1: A graphical history of personal computers in the 1970’s, the MITS Altair and Apple Computer era. Microprocessors in the 1970’s 3/3 Figure 3.2: Andrew S. Grove, Robert N. Noyce and Gordon E. Moore. Figure 3.3: Marcian E. “Ted” Hoff. Photographs are courtesy of Intel Corporation. 3/4 Part II 1970’s -- The Altair/Apple era Figure 3.4: The Intel MCS-4 (Micro Computer System 4) basic system. Figure 3.5: A photomicrograph of the Intel 4004 microprocessor. Photographs are courtesy of Intel Corporation. Chapter 3 Microprocessors in the 1970's The creation of the transistor in 1947 and the development of the integrated circuit in 1958/59, is the technology that formed the basis for the microprocessor. Initially the technology only enabled a restricted number of components on a single chip. However this changed significantly in the following years. The technology evolved from Small Scale Integration (SSI) in the early 1960's to Medium Scale Integration (MSI) with a few hundred components in the mid 1960's. By the late 1960's LSI (Large Scale Integration) chips with thousands of components had occurred. This rapid increase in the number of components in an integrated circuit led to what became known as Moore’s Law. The concept of this law was described by Gordon Moore in an article entitled “Cramming More Components Onto Integrated Circuits” in the April 1965 issue of Electronics magazine [338]. -

Resistors, Diodes, Transistors, and the Semiconductor Value of a Resistor

Resistors, Diodes, Transistors, and the Semiconductor Value of a Resistor Most resistors look like the following: A Four-Band Resistor As you can see, there are four color-coded bands on the resistor. The value of the resistor is encoded into them. We will follow the procedure below to decode this value. • When determining the value of a resistor, orient it so the gold or silver band is on the right, as shown above. • You can now decode what resistance value the above resistor has by using the table on the following page. • We start on the left with the first band, which is BLUE in this case. So the first digit of the resistor value is 6 as indicated in the table. • Then we move to the next band to the right, which is GREEN in this case. So the second digit of the resistor value is 5 as indicated in the table. • The next band to the right, the third one, is RED. This is the multiplier of the resistor value, which is 100 as indicated in the table. • Finally, the last band on the right is the GOLD band. This is the tolerance of the resistor value, which is 5%. The fourth band always indicates the tolerance of the resistor. • We now put the first digit and the second digit next to each other to create a value. In this case, it’s 65. 6 next to 5 is 65. • Then we multiply that by the multiplier, which is 100. 65 x 100 = 6,500. • And the last band tells us that there is a 5% tolerance on the total of 6500.