Namaqualand and Challenges to the Law Community Resource

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Immediate and Long-Term Effects of Namibia's Colonization Process

The Immediate and Long-Term Effects of Namibia’s Colonization Process By: Jonathan Baker Honors Capstone Through Professor Taylor Politics of Sub-Saharan Africa Baker, 2 Table of Contents I. Authors Note II. Introduction III. Pre-Colonization IV. Colonization by Germany V. Colonization by South Africa VI. The Struggle for Independence VII. The Decolonization Process VIII. Political Changes- A Reaction to Colonization IX. Immediate Economic Changes Brought on by Independence X. Long Term Political Effects (of Colonization) XI. Long Term Cultural Effects XII. Long Term Economic Effects XIII. Prospects for the Future XIV. Conclusion XV. Bibliography XVI. Appendices Baker, 3 I. Author’s Note I learned such a great deal from this entire honors capstone project, that all the knowledge I have acquired can hardly be covered by what I wrote in these 50 pages. I learned so much more that I was not able to share both about Namibia and myself. I can now claim that I am knowledgeable about nearly all areas of Namibian history and life. I certainly am no expert, but after all of this research I can certainly consider myself reliable. I have never had such an extensive knowledge before of one academic area as a result of a school project. I also learned a lot about myself through this project. I learned how I can motivate myself to work, and I learned how I perform when I have to organize such a long and complicated paper, just to name a couple of things. The strange inability to be able to include everything I learned from doing this project is the reason for some of the more random appendices at the end, as I have a passion for both numbers and trivia. -

6 the Environments Associated with the Proposed Alternative Sites

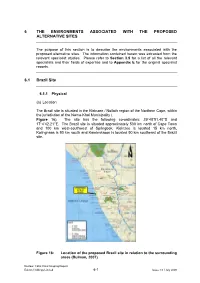

6 THE ENVIRONMENTS ASSOCIATED WITH THE PROPOSED ALTERNATIVE SITES The purpose of this section is to describe the environments associated with the proposed alternative sites. The information contained herein was extracted from the relevant specialist studies. Please refer to Section 3.5 for a list of all the relevant specialists and their fields of expertise and to Appendix E for the original specialist reports. 6.1 Brazil Site 6.1.1 Physical (a) Location The Brazil site is situated in the Kleinzee / Nolloth region of the Northern Cape, within the jurisdiction of the Nama-Khoi Municipality ( Figure 16). The site has the following co-ordinates: 29°48’51.40’’S and 17°4’42.21’’E. The Brazil site is situated approximately 500 km north of Cape Town and 100 km west-southwest of Springbok. Kleinzee is located 15 km north, Koiingnaas is 90 km south and Kamieskroon is located 90 km southeast of the Brazil site. Figure 16: Location of the proposed Brazil site in relation to the surrounding areas (Bulman, 2007) Nuclear 1 EIA: Final Scoping Report Eskom Holdings Limited 6-1 Issue 1.0 / July 2008 (b) Topography The topography in the Brazil region is largely flat, with only a gentle slope down to the coast. The coast is composed of both sandy and rocky shores. The topography is characterised by a small fore-dune complex immediately adjacent to the coast with the highest elevation of approximately nine mamsl. Further inland the general elevation depresses to about five mamsl in the middle of the study area and then gradually rises towards the east. -

Explore the Northern Cape Province

Cultural Guiding - Explore The Northern Cape Province When Schalk van Niekerk traded all his possessions for an 83.5 carat stone owned by the Griqua Shepard, Zwartboy, Sir Richard Southey, Colonial Secretary of the Cape, declared with some justification: “This is the rock on which the future of South Africa will be built.” For us, The Star of South Africa, as the gem became known, shines not in the East, but in the Northern Cape. (Tourism Blueprint, 2006) 2 – WildlifeCampus Cultural Guiding Course – Northern Cape Module # 1 - Province Overview Component # 1 - Northern Cape Province Overview Module # 2 - Cultural Overview Component # 1 - Northern Cape Cultural Overview Module # 3 - Historical Overview Component # 1 - Northern Cape Historical Overview Module # 4 - Wildlife and Nature Conservation Overview Component # 1 - Northern Cape Wildlife and Nature Conservation Overview Module # 5 - Namaqualand Component # 1 - Namaqualand Component # 2 - The Hantam Karoo Component # 3 - Towns along the N14 Component # 4 - Richtersveld Component # 5 - The West Coast Module # 5 - Karoo Region Component # 1 - Introduction to the Karoo and N12 towns Component # 2 - Towns along the N1, N9 and N10 Component # 3 - Other Karoo towns Module # 6 - Diamond Region Component # 1 - Kimberley Component # 2 - Battlefields and towns along the N12 Module # 7 - The Green Kalahari Component # 1 – The Green Kalahari Module # 8 - The Kalahari Component # 1 - Kuruman and towns along the N14 South and R31 Northern Cape Province Overview This course material is the copyrighted intellectual property of WildlifeCampus. It may not be copied, distributed or reproduced in any format whatsoever without the express written permission of WildlifeCampus. 3 – WildlifeCampus Cultural Guiding Course – Northern Cape Module 1 - Component 1 Northern Cape Province Overview Introduction Diamonds certainly put the Northern Cape on the map, but it has far more to offer than these shiny stones. -

Tourism Is a National Priority and Contributes Signif- Icantly to Economic Development

Tourism is a national priority and contributes signif- icantly to economic development. The national tourism sector strategy provides a blueprint for the sector to meet the growth targets contained in the new growth path. The National Department of Tourism's (NDT) strategic goals over the medium term are to: • maximise domestic tourism and foreign tourist arrivals in South Africa • expand domestic and foreign investment in the South African tourism industry • expand tourist infrastructure • improve the range and quality of tourist services • improve the tourist experience and value for money • improve research and knowledge management • contribute to growth and development and expand the tourism share of gross domestic product (GDP) • improve competitiveness and sustainability in the tourism sector • strengthen collaboration with tourist organi sations. The inflow of tourists to South Africa is the result of the success of policies aimed at entrenching South Africa’s status as a major international tourism and business events destination. The Tourism Business Index’s quarterly index produced by the Tourism Business Council of South Africa indicated that revenue per available room in the hotel sector increased by 7,9% during the first 10 months of 2014. A Statistics South Africa (StatsSA) report has found that the total income for the South Africa tourist accommo- dation industry, which includes restaurant and bar sales, grew by 7%. In May 2015, there were 1 202 795 foreign arrivals to South Africa. The arrivals were made up of 89 257 non-visitors and 1 113 538 visitors. The visitors consisted of 428 131 same-day visitors and 685 407 overnight visitors. -

Kamieskroon Bulk Water Supply, Portion 4 of Farm 445, Kamiesberg Municipality, Northern Cape

1 PALAEONTOLOGICAL HERITAGE COMMENT: KAMIESKROON BULK WATER SUPPLY, PORTION 4 OF FARM 445, KAMIESBERG MUNICIPALITY, NORTHERN CAPE John E. Almond PhD (Cantab.) Natura Viva cc, PO Box 12410 Mill Street, Cape Town 8010, RSA [email protected] January 2018 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The overall palaeontological impact significance of the proposed Bulk Water Supply System development on Portion 4 of Farm 445 near Kamieskroon, Namaqualand, Northern Cape, is considered to be VERY LOW because the study area is underlain by unfossiliferous metamorphic basement rocks (granite-gneisses, migmatites etc) and / or mantled by superficial sediments of low palaeontological sensitivity while the development footprint is very small and in part already disturbed. It is therefore recommended that, pending the exposure of significant new fossils during development, exemption from further specialist palaeontological studies and mitigation be granted for this development. 1. PROJECT OUTLINE The proposed Bulk Water Supply System development on Portion 4 of Farm 445 near Kamieskroon, Kamiesberg Municipality, Northern Cape involves the following infrastructural components (CTS Heritage 2017; Fig. 1): • equipment for existing boreholes; • equipment for additional boreholes; • construction of a 600kl clean water storage reservoir; • installation of pipelines; • construction of a Water Treatment Works (desalination plant) and associated evaporation ponds (waste brine). 2. GEOLOGICAL CONTEXT The footprint of the proposed Bulk Water Supply System development is situated at c. 770 m asl in fairly flat, disturbed, semi-arid, rocky terrain on the outskirts of the town of Kamieskroon, some 600 m southeast of the N7 trunk road (Fig. 1). The geology of the study area near Kamieskroon is shown on the 1: 250 000 geology map 3017 Garies (Council for Geoscience, Pretoria; Fig. -

10 Year Report 1

DOCKDA Rural Development Agency: 1994–2004 Celebrating Ten Years of Rural Development DOCKDA 10 year report 1 A Decade of Democracy 2 Globalisation and African Renewal 2 Rural Development in the Context of Globalisation 3 Becoming a Rural Development Agency 6 Organogram 7 Indaba 2002 8 Indaba 2004 8 Monitoring and Evaluation 9 Donor Partners 9 Achievements: 1994–2004 10 Challenges: 1994–2004 11 Namakwa Katolieke Ontwikkeling (Namko) 13 Katolieke Ontwikkeling Oranje Rivier (KOOR) 16 Hopetown Advice and Development Office (HADO) 17 Bisdom van Oudtshoorn Katolieke Ontwikkeling (BOKO) 18 Gariep Development Office (GARDO) 19 Karoo Mobilisasie, Beplanning en Rekonstruksie Organisasie (KAMBRO) 19 Sectoral Grant Making 20 Capacity Building for Organisational Development 27 Early Childhood Development Self-reliance Programme 29 HIV and AIDS Programme 31 2 Ten Years of Rural Development A Decade of Democracy In 1997, DOCKDA, in a publication summarising the work of the organisation in the first three years of The first ten years of the new democracy in South Africa operation, noted that it was hoped that the trickle-down coincided with the celebration of the first ten years approach of GEAR would result in a steady spread of of DOCKDA’s work in the field of rural development. wealth to poor people.1 In reality, though, GEAR has South Africa experienced extensive changes during failed the poor. According to the Human Development this period, some for the better, some not positive at Report 2003, South Africans were poorer in 2003 than all. A central change was the shift, in 1996, from the they were in 1995.2 Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP) to the Growth, Employment and Redistribution Strategy Globalisation and African Renewal (GEAR). -

Thesis Hum 2010 Bregman Joel.Pdf

Town The copyright of this thesis rests with the University of Cape Town. No quotation from it or information derivedCape from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of theof source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non-commercial research purposes only. University Land and Society in the Komaggas region of Namaqualand Joel Bregman BRGJOE001 A dissertation submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Master of Arts in Historical Studies Faculty of the Humanities University of Cape Town 2010 Town COMPULSORY DECLARATION This work has not been previously submitted in whole,Cape or in part, for the award of any degree. It is my own work. Each significant contribution to, and quotation in, this dissertation from the work, or works, of other people has been attributed, and has been cited and referenced. Of Signature: Date: University Land and Society in the Komaggas region of Namaqualand Joel Bregman (University of Cape Town) Abstract: This paper explores the history of Namaqualand and specifically the Komaggas community. By taking note of the major developments that occurred in the area, the effects on this community over the last 200 or so years have been established. The focal point follows the history of land; its usage, dispossession and importance to the survival of Namaqualanders. Using the records of travellers to the region, the views of government officials, local inhabitants as well as numerous analyses of contemporary authors, a detailed understanding of this area has emerged. Among other things, the research has attempted to ascertain whether the current Komaggas community has a claim to a greater portion of land than it currently holds. -

14 Northern Cape Province

Section B:Section Profile B:Northern District HealthCape Province Profiles 14 Northern Cape Province John Taolo Gaetsewe District Municipality (DC45) Overview of the district The John Taolo Gaetsewe District Municipalitya (previously Kgalagadi) is a Category C municipality located in the north of the Northern Cape Province, bordering Botswana in the west. It comprises the three local municipalities of Gamagara, Ga- Segonyana and Joe Morolong, and 186 towns and settlements, of which the majority (80%) are villages. The boundaries of this district were demarcated in 2006 to include the once north-western part of Joe Morolong and Olifantshoek, along with its surrounds, into the Gamagara Local Municipality. It has an established rail network from Sishen South and between Black Rock and Dibeng. It is characterised by a mixture of land uses, of which agriculture and mining are dominant. The district holds potential as a viable tourist destination and has numerous growth opportunities in the industrial sector. Area: 27 322km² Population (2016)b: 238 306 Population density (2016): 8.7 persons per km2 Estimated medical scheme coverage: 14.5% Cities/Towns: Bankhara-Bodulong, Deben, Hotazel, Kathu, Kuruman, Mothibistad, Olifantshoek, Santoy, Van Zylsrus. Main Economic Sectors: Agriculture, mining, retail. Population distribution, local municipality boundaries and health facility locations Source: Mid-Year Population Estimates 2016, Stats SA. a The Local Government Handbook South Africa 2017. A complete guide to municipalities in South Africa. Seventh -

Draft Management Plan Swartlintjies

DRAFT MANAGEMENT PLAN FOR THE SWARTLINTJIES ESTUARY . March 2017 Prepared by: Pete Fielding - FieldWork 57 Jarvis Rd Berea East London 5240 Anchor Environmental – Vera Massey and Barry Clark 8 Steenberg House, Silverwood Close, Tokai 7945, South Africa 1 This document forms the second deliverable towards the development of an Estuary Management Plan for the Swartlintjies Estuary, which falls within the Kamiesberg Local Municipal area. Kamiesberg LM is located within the Namakwa District Municipality. This is the Draft Estuary Management Plan which lays out the Vision, Objectives, Goals, and Management Actions required to achieve those Goals for the Swartlintjies Estuary. 2 Contents ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ...................................................................................................... 5 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................... 7 1.1 BACKGROUND ........................................................................................................................... 7 1.2 PURPOSE AND SCOPE OF THE SWARTLINTJIES ESTUARY MANAGEMENT PLAN ...................... 8 1.3 STRUCTURE OF THE REPORT ..................................................................................................... 9 2. SYNOPSIS OF SITUATION ASSESSMENT ........................................................................................ 10 2.1 PRESENT ECOLOGICAL STATE AND DESIRED ECOLOGICAL STATE ......................................... -

Rooifontein Bulk Water Supply on the Remainder of Leliefontein 614, Kamiesberg Municipality, Northern Cape

1 PALAEONTOLOGICAL HERITAGE COMMENT: ROOIFONTEIN BULK WATER SUPPLY ON THE REMAINDER OF LELIEFONTEIN 614, KAMIESBERG MUNICIPALITY, NORTHERN CAPE John E. Almond PhD (Cantab.) Natura Viva cc, PO Box 12410 Mill Street, Cape Town 8010, RSA [email protected] January 2018 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The overall palaeontological impact significance of the proposed Bulk Water Supply System development on the Remainder of Leliefontein 614 near Rooifontein, Namaqualand klipkoppe region of the Northern Cape, is considered to be LOW. This is because the study area is underlain by unfossiliferous metamorphic basement rocks (granite-gneisses etc) and / or mantled by superficial sediments of low palaeontological sensitivity (e.g. alluvium of the Buffelsrivier), while the development footprint is very small. It is therefore recommended that, pending the exposure of significant new fossils during development, exemption from further specialist palaeontological studies and mitigation be granted for this development. The archaeologist carrying out the field assessment of the study area should report to SAHRA any substantial unmapped areas of alluvial gravels or well-consolidated finer alluvial sediments encountered, since these might contain fossil bones and teeth of mammals. 1. PROJECT OUTLINE The proposed Bulk Water Supply System development on the Remainder of Leliefontein 614 near Rooifontein, Kamiesberg Municipality, Northern Cape involves the following infrastructural components (CTS Heritage 2017; Fig. 1): • Equipment for existing boreholes; • Equipment for additional boreholes; • Construction of a 190 kl steel panel reservoir; • Installation of approximately 6km of pipelines; • Construction of a Water Treatment Works (desalination plant) and associated evaporation ponds (waste brine). 2. GEOLOGICAL CONTEXT The footprint of the proposed Bulk Water Supply System development is situated at c. -

Western Cape & Northern Cape

JUNO-GROMIS 400kV POWER LINE (WESTERN CAPE & NORTHERN CAPE) DESK TOP STUDY PALAEONTOLOGY Compiled by: Dr JF Durand (Sci.Nat.) For: Nsovo Environmental Consulting Tel: +2711 312 9984 Cel: +2781 217 8130 Fax: 086 602 8821 Email: [email protected] 8 January 2017 1 Table of Contents: 1. Introduction……………………………………………………………………....................3 2. Terms of reference for the report………………………………………………................4 3. Details of study area and the type of assessment……………………………………...7 4. Geological setting…………………………………………………………………………..8 5. Palaeontological potential of the study area…………………………..………………. 14 6. Conclusion and Recommendations………… ………………………………………..27 List of Figures: Figure 1: Google Earth photo indicating the study area……...………………….………....7 Figure 2: Geology underlying the proposed Juno-Gromis Power Line (adapted from the 1: 1 000 000 Geology Map for South Africa, Geological Survey, 1970)…………………..8 Figure 3: Simplified geology of the study area (adapted from the 1:2 000 000 geology map - Council for Geoscience, 2008)………………………………………………………....9 Figure 4: West Coast pedogenic duricrusts (adapted from Partridge et al., 2009)….....10 Figure 5: Distribution of coastal Cenozoic sediments along the West Coast (adapted from Roberts et al., 2009)…………………………………………………………………….11 Figure 6: Stratigraphy of the West Coast Group (after De Beer, 2010)………………….12 Figure 7: Lithostratigraphy of the Cenozoic West Coast Group on the 3017 Garies geological map (from De Beer, 2010)……………………………………………………….13 Figure 8: Palaeontological Sensitivity Map of -

The Ovaherero/Nama Genocide: a Case for an Apology and Reparations

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by European Scientific Journal (European Scientific Institute) European Scientific Journal June 2017 /SPECIAL/ edition ISSN: 1857 – 7881 (Print) e - ISSN 1857- 7431 The Ovaherero/Nama Genocide: A Case for an Apology and Reparations Nick Sprenger Robert G. Rodriguez, PhD Texas A&M University-Commerce Ngondi A. Kamaṱuka, PhD University of Kansas Abstract This research examines the consequences of the Ovaherero and Nama massacres occurring in modern Namibia from 1904-08 and perpetuated by Imperial Germany. Recent political advances made by, among other groups, the Association of the Ovaherero Genocide in the United States of America, toward mutual understanding with the Federal Republic of Germany necessitates a comprehensive study about the event itself, its long-term implications, and the more current vocalization toward an apology and reparations for the Ovaherero and Nama peoples. Resulting from the Extermination Orders of 1904 and 1905 as articulated by Kaiser Wilhelm II’s Imperial Germany, over 65,000 Ovaherero and 10,000 Nama peoples perished in what was the first systematic genocide of the twentieth century. This study assesses the historical circumstances surrounding these genocidal policies carried out by Imperial Germany, and seeks to place the devastating loss of life, culture, and property within its proper historical context. The question of restorative justice also receives analysis, as this research evaluates the case made by the Ovaherero and Nama peoples in their petitions for compensation. Beyond the history of the event itself and its long-term effects, the paper adopts a comparative approach by which to integrate the Ovaherero and Nama calls for reparations into an established precedent.