Thesis Hum 2010 Bregman Joel.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

6 the Environments Associated with the Proposed Alternative Sites

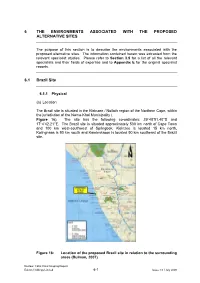

6 THE ENVIRONMENTS ASSOCIATED WITH THE PROPOSED ALTERNATIVE SITES The purpose of this section is to describe the environments associated with the proposed alternative sites. The information contained herein was extracted from the relevant specialist studies. Please refer to Section 3.5 for a list of all the relevant specialists and their fields of expertise and to Appendix E for the original specialist reports. 6.1 Brazil Site 6.1.1 Physical (a) Location The Brazil site is situated in the Kleinzee / Nolloth region of the Northern Cape, within the jurisdiction of the Nama-Khoi Municipality ( Figure 16). The site has the following co-ordinates: 29°48’51.40’’S and 17°4’42.21’’E. The Brazil site is situated approximately 500 km north of Cape Town and 100 km west-southwest of Springbok. Kleinzee is located 15 km north, Koiingnaas is 90 km south and Kamieskroon is located 90 km southeast of the Brazil site. Figure 16: Location of the proposed Brazil site in relation to the surrounding areas (Bulman, 2007) Nuclear 1 EIA: Final Scoping Report Eskom Holdings Limited 6-1 Issue 1.0 / July 2008 (b) Topography The topography in the Brazil region is largely flat, with only a gentle slope down to the coast. The coast is composed of both sandy and rocky shores. The topography is characterised by a small fore-dune complex immediately adjacent to the coast with the highest elevation of approximately nine mamsl. Further inland the general elevation depresses to about five mamsl in the middle of the study area and then gradually rises towards the east. -

Namaqualand and Challenges to the Law Community Resource

•' **• • v ^ WiKSHOr'IMPOLITICIALT ... , , AWD POLICY ANALYSi • ; ' st9K«onTHp^n»< '" •wJ^B^W-'EP.SrTY NAMAQUALAND AND CHALLENGES TO THE LAW: COMMUNITY RESOURCE MANAGEMENT AND LEGAL FRAMEWORKS Henk Smith Land reform in the arid Namaqualand region of South Africa offers unique challenges. Most of the land is owned by large mining companies and white commercial farmers. The government's restitution programme which addresses dispossession under post 1913 Apartheid land laws, will not be the major instrument for land reform in Namaqualand. Most dispossession of indigenous Nama people occurred during the previous century or the State was not directly involved. Redistribution and land acquisition for those in need of land based income opportunities and qualifying for State assistance will to some extent deal with unequal land distribution pattern. Surface use of mining land, and small mining compatible with large-scale mining may provide new opportunities for redistribution purposes. The most dramatic land reform measures in Namaqualand will be in the field of tenure reform, and specifically of communal tenure systems. Namaqualand features eight large reserves (1 200 OOOha covering 25% of the area) set aside for the local communities. These reserves have a history which is unique in South Africa. During the 1800's as the interior of South Africa was being colonised, the rights of Nama descendant communities were recognised through State issued "tickets of occupation". Subsequent legislation designed to administer these exclusively Coloured areas, confirmed that the communities' interests in land predating the legislation. A statutory trust of this sort creates obligations for the State in public law. Furthermore, the new constitution insists on appropriate respect for the fundamental principles of non-discrimination and freedom of movement. -

10 Year Report 1

DOCKDA Rural Development Agency: 1994–2004 Celebrating Ten Years of Rural Development DOCKDA 10 year report 1 A Decade of Democracy 2 Globalisation and African Renewal 2 Rural Development in the Context of Globalisation 3 Becoming a Rural Development Agency 6 Organogram 7 Indaba 2002 8 Indaba 2004 8 Monitoring and Evaluation 9 Donor Partners 9 Achievements: 1994–2004 10 Challenges: 1994–2004 11 Namakwa Katolieke Ontwikkeling (Namko) 13 Katolieke Ontwikkeling Oranje Rivier (KOOR) 16 Hopetown Advice and Development Office (HADO) 17 Bisdom van Oudtshoorn Katolieke Ontwikkeling (BOKO) 18 Gariep Development Office (GARDO) 19 Karoo Mobilisasie, Beplanning en Rekonstruksie Organisasie (KAMBRO) 19 Sectoral Grant Making 20 Capacity Building for Organisational Development 27 Early Childhood Development Self-reliance Programme 29 HIV and AIDS Programme 31 2 Ten Years of Rural Development A Decade of Democracy In 1997, DOCKDA, in a publication summarising the work of the organisation in the first three years of The first ten years of the new democracy in South Africa operation, noted that it was hoped that the trickle-down coincided with the celebration of the first ten years approach of GEAR would result in a steady spread of of DOCKDA’s work in the field of rural development. wealth to poor people.1 In reality, though, GEAR has South Africa experienced extensive changes during failed the poor. According to the Human Development this period, some for the better, some not positive at Report 2003, South Africans were poorer in 2003 than all. A central change was the shift, in 1996, from the they were in 1995.2 Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP) to the Growth, Employment and Redistribution Strategy Globalisation and African Renewal (GEAR). -

14 Northern Cape Province

Section B:Section Profile B:Northern District HealthCape Province Profiles 14 Northern Cape Province John Taolo Gaetsewe District Municipality (DC45) Overview of the district The John Taolo Gaetsewe District Municipalitya (previously Kgalagadi) is a Category C municipality located in the north of the Northern Cape Province, bordering Botswana in the west. It comprises the three local municipalities of Gamagara, Ga- Segonyana and Joe Morolong, and 186 towns and settlements, of which the majority (80%) are villages. The boundaries of this district were demarcated in 2006 to include the once north-western part of Joe Morolong and Olifantshoek, along with its surrounds, into the Gamagara Local Municipality. It has an established rail network from Sishen South and between Black Rock and Dibeng. It is characterised by a mixture of land uses, of which agriculture and mining are dominant. The district holds potential as a viable tourist destination and has numerous growth opportunities in the industrial sector. Area: 27 322km² Population (2016)b: 238 306 Population density (2016): 8.7 persons per km2 Estimated medical scheme coverage: 14.5% Cities/Towns: Bankhara-Bodulong, Deben, Hotazel, Kathu, Kuruman, Mothibistad, Olifantshoek, Santoy, Van Zylsrus. Main Economic Sectors: Agriculture, mining, retail. Population distribution, local municipality boundaries and health facility locations Source: Mid-Year Population Estimates 2016, Stats SA. a The Local Government Handbook South Africa 2017. A complete guide to municipalities in South Africa. Seventh -

Nc Travelguide 2016 1 7.68 MB

Experience Northern CapeSouth Africa NORTHERN CAPE TOURISM AUTHORITY Tel: +27 (0) 53 832 2657 · Fax +27 (0) 53 831 2937 Email:[email protected] www.experiencenortherncape.com 2016 Edition www.experiencenortherncape.com 1 Experience the Northern Cape Majestically covering more Mining for holiday than 360 000 square kilometres accommodation from the world-renowned Kalahari Desert in the ideas? North to the arid plains of the Karoo in the South, the Northern Cape Province of South Africa offers Explore Kimberley’s visitors an unforgettable holiday experience. self-catering accommodation Characterised by its open spaces, friendly people, options at two of our rich history and unique cultural diversity, finest conservation reserves, Rooipoort and this land of the extreme promises an unparalleled Dronfield. tourism destination of extreme nature, real culture and extreme adventure. Call 053 839 4455 to book. The province is easily accessible and served by the Kimberley and Upington airports with daily flights from Johannesburg and Cape Town. ROOIPOORT DRONFIELD Charter options from Windhoek, Activities Activities Victoria Falls and an internal • Game viewing • Game viewing aerial network make the exploration • Bird watching • Bird watching • Bushmen petroglyphs • Vulture hide of all five regions possible. • National Heritage Site • Swimming pool • Self-drive is allowed Accommodation The province is divided into five Rooipoort has a variety of self- Accommodation regions and boasts a total catering accommodation to offer. • 6 fully-equipped • “The Shooting Box” self-catering chalets of six national parks, including sleeps 12 people sharing • Consists of 3 family units two Transfrontier parks crossing • Box Cottage and 3 open plan units sleeps 4 people sharing into world-famous safari • Luxury Tented Camp destinations such as Namibia accommodation andThis Botswanais the world of asOrange well River as Cellars. -

Integrated Development Plan 2012 – 2016

Namakwa District Municipality Integrated Development Plan 2012 – 2016 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Forward: Executive Mayor 3 Forward: Municipal Manager 4 1. BACKGROUND 5 1.1. Introduction 5 2. DISTRICT ANALYSIS AND PROFILE 5 2.1. Municipal Area Analysis 5 2.2. Demographic Analysis 7 2.3. Migration 8 2.4. Economic Analysis 9 2.5. Climate Change 12 2.6. Environmental Management Framework 14 3. NEED ANALYSIS/PRIORITIES BY B-MUNICPALITIES 17 4. STRATEGIC GUIDES AND OBJECTIVES 30 4.1. National 30 4.2. Provincial 34 4.3. District 35 4.4. Institutional Structures 37 5. DEVELOPMENTAL PROJECTS 38 5.1. Priority List per Municipality 46 5.2. Sectoral Projects/Programmes 53 5.3. Five Year Implementation Plan 100 6. APPROVAL 155 7. ANNEXURE 155 Process Plan 2012/2013 - Annexure A 156 2 Forward Executive Mayor 3 Forward Municipal Manager 4 1. BACKGROUND 1.1. Introduction The District Municipality, a category C-Municipality, is obliged to compile an Integrated Development Plan (IDP) for its jurisdiction area, in terms of legislation. This IDP is the third cycle of this process and is for the period 2012-2016. The IDP is a strategic plan to guide the development of the District for the specific period. It guides the planning, budgeting, implementation management and future decision making processes of the municipality. This whole strategic process must be aligned and are subject to all National and Provincial Planning instruments and guidelines (See attached summarized list). The compilation of the IDP is managed through an IDP Steering Committee, which consists of municipal officials, managers of departments and is chaired by the Municipal Manager. -

High Altitude Integrated Natural Resource

DEAD OR ALIVE? HUMAN RIGHTS AND LAND REFORM IN NAMAQUALAND COMMONS, SOUTH AFRICA PAPER PRESENTED AT THE BIENNUAL CONFERENCE OF THE INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR THE STUDY OF COMMON PROPERTY, ‘THE COMMONS IN AN AGE OF GLOBALISATION’, VICTORIA FALLS, ZIMBABWE, JUNE 2002 POUL WISBORG1 MARCH 2002 1 PhD Research Fellow, Centre for International Environment and Development Studies, Noragric, Agricultural University of Norway and Programme for Land and Agrarian Studies (PLAAS), School of Government, University of Western Cape, Bellville, South Africa Abstract Dead or alive? Human rights and land reform in Namaqualand commons, South Africa Land tenure is emerging as a controversial human rights issue in both local resource conflicts and globalised rhetoric. While access to land is not a human right according to international law, many tenets concerning the right to food and a secure livelihood, to redress for past violations, to rule of law, non-discrimination and democracy apply to land governance. The relevance of the human rights talk for development is contested. Harri Englund’s notion of “the dead hand of human rights” refers to the gaps between global and local discourses. Land, particularly the commons, may be a problematic human rights issue because local idioms of ownership are embedded, elusive and flexible, and therefore difficult to codify and protect by national or international regimes. Furthermore, the economic pressures of globalisation may contradict civil-political rights and opportunities, leading Upendra Baxi to discuss whether and how there is a ‘future for human rights’. Based on fieldwork in two communal areas, the paper examines rights perceptions in a process of reforming communal land governance in Namaqualand, South Africa. -

Flower Route Map 2017

K o n k i e p en w R31 Lö Narubis Vredeshoop Gawachub R360 Grünau Karasburg Rosh Pinah R360 Ariamsvlei R32 e N14 ng Ora N10 Upington N10 IAi-IAis/Richtersveld Transfrontier Park Augrabies N14 e g Keimoes Kuboes n a Oranjemund r Flower Hotlines O H a ib R359 Holgat Kakamas Alexander Bay Nababeep N14 Nature Reserve R358 Groblershoop N8 N8 Or a For up-to-date information on where to see the Vioolsdrif nge H R27 VIEWING TIPS best owers, please call: Eksteenfontein a r t e b e e Namakwa +27 (0)72 760 6019 N7 i s Pella t Lekkersing t Brak u Weskus +27 (0)63 724 6203 o N10 Pofadder S R383 R383 Aggeneys Flower Hour i R382 Kenhardt To view the owers at their best, choose the hottest Steinkopf R363 Port Nolloth N14 Marydale time of the day, which is from 11h00 to 15h00. It’s the s in extended ower power hour. Respect the ower Tu McDougall’s Bay paradise: Walk with care and don’t trample plants R358 unnecessarily. Please don’t pick any buds, bulbs or N10 specimens, nor disturb any sensitive dune areas. Concordia R361 R355 Nababeep Okiep DISTANCE TABLE Prieska Goegap Nature Reserve Sun Run fels Molyneux Buf R355 Springbok R27 The owers always face the sun. Try and drive towards Nature Reserve Grootmis R355 the sun to enjoy nature’s dazzling display. When viewing Kleinzee Naries i R357 i owers on foot, stand with the sun behind your back. R361 Copperton Certain owers don’t open when it’s overcast. -

Annual Report 2008/09

ANNUAL REPORT 2008/09 In terms of section 46 of the Municipal Systems Act and Section 121 of the Municipal Finance Management Act TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 1 - INTRODUCTION AND OVERVIEW ___________________________________________________________________________ 3 1.1 MAYOR’S FOREWORD .................................................................................................................................................................................................................. 4 1.2 OVERVIEW OF NAMA KHOI MUNICIPALITY ......................................................................................................................................................................... 5 1.3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 6 CHAPTER 2 - PERFORMANCE HIGHLIGHTS ______________________________________________________________________________ 16 2.1 OFFICE OF THE MUNICIPAL MANAGER ................................................................................................................................................................................16 2.2 DEPARTMENT COMMUNITY SERVICES .................................................................................................................................................................................49 2.3 DEPARTMENT FINANCIAL SERVICES .....................................................................................................................................................................................72 -

Volume 4 Compressed Part22.Pdf

List of Figures Figure 1.1: Location of study area and mining rights area ... ............................................. 2 Figure 2.1 : Location of development corridors in the Northern Cape Province ............ 24 Figure 2.2 : Location of mining focus areas in the Northern Cape Province ................. 25 Figure 3.1 : Location of the Kamiesberg and Nama Khoi Local Municipalities within the Namaqua DM ............ ........... .... .. .. .... .. ................................... ...................... .. .. ....................... 31 r Figure 3.2: Percentage of people living in poverty in the Northern Cape ..................... 33 Figure 3.3: Percentage of household income below the poverty breadline by District ..... ................. .. ... ......... ................... .. ..................... .... ... .. .. ............... .. .. ... ..... ................ ...... .. 34 r Figure 3.4: Employment by Economic Sector and Industry .. ............................................ 35 List of Tables r Table 3.1 : Overview of key demographic indicators for NDM, NKLM and KLM ...... .. .... 37 Table 3.2: Overview of access to basic services in NDM, NKLM and KLM ..................... 38 Table 4.1 : Towns of origin for workers ................... .. .. .. .. .. ................................................. .. .. 42 Table 4.2: Assessment of employment opportunities ........................................................ 43 Table 4.3: Assessment of training and skills development opportunities ..................... .44 Table 4.4: Assessment -

April 2016 Active Stations Used for Groundwater Level Monitoring

17° 18° 19° 20° 21° 22° 23° 24° 25° 26° 27° 28° 29° 30° 31° 32° Z II M B A B W E 22° 22° !( !( MUSINA !( !( (! !( !( !( !( !(!( !( !( !( !(!( !( Mopane !( !( !( !( !( !( !( Alldays!( !( Tshipise !( ! !( !( !( !( !( !( !( ! !( !( !( P!(undu!( Maria !( Swartwater!( !( !(!( !( !( !( ! !( !( ! !( B!(uysd!(orp !( !( M 23° !( !( !( !( !( M 23° Tom Bu!(rke !( !( !( !( ! !( !( !( !( !(Bochum Mogwad!(i Active Stations Used For B O T S W A N A !( !( !(! !( !( !( O B O T S W A N A !( Ga-Ramokgo!(pa O !( !( ! !( !( ! !( Rebone !( !( ! !( !( !( !( !( M!(orebeng !( Z Groundwater Level Monitoring !( !( !( !( !( !( !(!( !( Z !( !( !( !( !( !( !(!(!( !( A ! A B!(akenberg Mmotong !( !(!(!( !( !( !( PHALABORWA !( !( (!( P!(OLO!(KWANE !((! !( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( M 24° !(!(!(!( !( M 24° !( Sent!(rum !( !( !(! !( !( !( ! ! !( M!(okopane !( !( !( !( Vaalwater !( B !( !( ! B !( !( !( Penge !( !( !( !( !( !( !( April 2016 !( !( I Dwaalboom Modimolle !( !( !( !(Steelpoort !(!( I ! !( !(! !( ! ! !(!(!( !( !(!( Q ! !( Q !( !( Ohrigstad !( Supingstadt Limp!(opo !( O l i f a n!( ts Inkomati - !( U 25° ! !( ! U 25° Tloonane Village Rapot!(okwane !( Usuthu Mokgola ! !( Data Sources: !( !( E ! Ga Mokgatlha !( !( !( !( E !( Nossob ! L!(!(ehurutshe !( !( !( !( ! (! !( !( !( ! Zeerust !( NELSPR!(!(!(UIT Water Management Areas: Directorate Catchment !( !( !(!( !( !( !( !(!( PRETO!RIA !(!(!( !(!(!(!(!(!( !( !(!( !( !( !( !( !(!( !( N A M II B II A ! !( !(!(!( !( !( !( !( !(!(!( !( !( (!!(!(!(!(!( !( Management. Boundaries and towns : Chief Mata-Mata !( !!( !(!(!( !( !( !(!(Ot!(tos!(h!(!(oop -

Fresh Water Report Komaggas

Nama Khoi Municipality WATER USE LICENSE APPLICATION FRESH WATER REPORT PROPOSED PIPELINE RECONSTRUCTION FOR THE WATER PROVISION OF KOMAGGAS A requirement in terms of Section 21 (c) and (i) of the National Water Act (36 of 1998) April 2020 WATSAN Africa KOMAGGAS PIPELINE RECONSTRUCTION 1 Index Abbreviations 3 List of Figures 4 List of Tables 4 1 Introduction 5 2 Legal Framework 6 3 Rainfall 7 4 Quaternary Catchment 7 5 Conservation Status 7 6 Vegetation 7 7 Buffels River Catchment 8 8 The Project 10 8.1 Current Infrastructure 10 8.2 The Terrain 11 8.3 Scope of Works 11 8.4 New Reservoirs 12 8.5 Refurbishment of Pipeline 13 8.5.1 First section next to Komaggas to 2.5km 13 8.5.2 Potential Impacts on the Aquatic Environment 15 8.5.3 Recommendations 15 8.5.4 The 2.5 km mark 16 8.5.5 Impacts at the 2.5km mark 16 8.5.6 Recommendations pertaining to the 2.5 km mark 18 8.6 From 2.5km to the Balancing Reservoir No. 3 18 8.7 From Reservoir 3 to Reservoir 2 20 8.8 Section of pipeline between Reservoir 2 and Reservoir 1 24 8.9 Pipeline between Reservoir 1 and Buffels River Reservoir 24 8.10 Boreholes 25 9 Water Abstraction 28 10 Access Roads 30 10.1 Possible Impacts 31 11 Electric Supply Lines 31 12 Retention Walls 32 13 Present Ecological State 32 14 Ecological Importance 35 15 Ecological Sensitivity 36 16 Impact Assessment 36 17 Risk Matrix 40 18 Resource Economics 42 19 Conclusions 44 20 References 46 21 Declaration 47 22 Résumé 48 23 Appendix 51 23.1 Namakwland Strandveld 51 23.2 Methodology for determining significance of impacts 52 23.3 Risk