10 Year Report 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Key Experiences of Land Reform in the Northern Cape Province of South

PR cov no. 1 1/18/05 4:09 PM Page c POLICY & RESEARCH SERIES Key Experiences 1 of Land Reform in the Northern Cape Province of South Africa Alastair Bradstock January 2005 PR book no. 1 1/18/05 4:01 PM Page i POLICY & RESEARCH SERIES Key Experiences 1 of Land Reform in the Northern Cape Province of South Africa Alastair Bradstock January 2005 PR book no. 1 1/18/05 4:01 PM Page ii Editors: Jacqueline Saunders and Lynne Slowey Photographs: Pieter Roos Designer: Eileen Higgins E [email protected] Printers: Waterside Press T +44 (0) 1707 275555 Copies of this publication are available from: FARM-Africa, 9-10 Southampton Place London,WC1A 2EA, UK T + 44 (0) 20 7430 0440 F + 44 (0) 20 7430 0460 E [email protected] W www.farmafrica.org.uk FARM-Africa (South Africa), 4th Floor,Trust Bank Building, Jones Street PO Box 2410, Kimberley 8300, Northern Cape, South Africa T + 27 (0) 53 831 8330 F + 27 (0) 53 831 8333 E [email protected] ISBN: 1 904029 02 7 Registered Charity No. 326901 Copyright: FARM-Africa, 2005 Registered Company No. 1926828 PR book no. 1 1/18/05 4:01 PM Page iii FARM-Africa’s Policy and Research Series encapsulates project experiences and research findings from its grassroots programmes in Eastern and Southern Africa.Aimed at national and international policy makers, national government staff, research institutions, NGOs and the international donor community, the series makes specific policy recommendations to enhance the productivity of the smallholder agricultural sector in Africa. -

6 the Environments Associated with the Proposed Alternative Sites

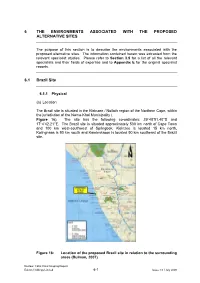

6 THE ENVIRONMENTS ASSOCIATED WITH THE PROPOSED ALTERNATIVE SITES The purpose of this section is to describe the environments associated with the proposed alternative sites. The information contained herein was extracted from the relevant specialist studies. Please refer to Section 3.5 for a list of all the relevant specialists and their fields of expertise and to Appendix E for the original specialist reports. 6.1 Brazil Site 6.1.1 Physical (a) Location The Brazil site is situated in the Kleinzee / Nolloth region of the Northern Cape, within the jurisdiction of the Nama-Khoi Municipality ( Figure 16). The site has the following co-ordinates: 29°48’51.40’’S and 17°4’42.21’’E. The Brazil site is situated approximately 500 km north of Cape Town and 100 km west-southwest of Springbok. Kleinzee is located 15 km north, Koiingnaas is 90 km south and Kamieskroon is located 90 km southeast of the Brazil site. Figure 16: Location of the proposed Brazil site in relation to the surrounding areas (Bulman, 2007) Nuclear 1 EIA: Final Scoping Report Eskom Holdings Limited 6-1 Issue 1.0 / July 2008 (b) Topography The topography in the Brazil region is largely flat, with only a gentle slope down to the coast. The coast is composed of both sandy and rocky shores. The topography is characterised by a small fore-dune complex immediately adjacent to the coast with the highest elevation of approximately nine mamsl. Further inland the general elevation depresses to about five mamsl in the middle of the study area and then gradually rises towards the east. -

General Description of the Environment

Environmental Scoping Study for the proposed extension of the 765 kV Hydra Substation and the proposed construction of an additional 765 kV Transmission power line between the Hydra and Gamma Substations, Northern Cape Province 6. GENERAL DESCRIPTION OF THE STUDY AREA ENVIRONMENT The existing Hydra Substation and Gamma Substations lie approximately 130 km apart, and are separated by a generally flat landscape, interrupted in the northern section by high broken ground and small ridges, and the Bulberg and Horseshoe Ridges in the south close to the Gamma Substation site. The broader study area falls within the Northern Cape Province and extends from the existing Hydra Substation near De Aar to the south near Victoria West, where the Gamma Substation is located. 6.1 Topography The study area is located within a generally flat area interrupted at intervals by a number of hills and ridges. The height above sea level, of the study area ranges from 1300 m to 1800 m. Prominent ridges within the study area the include Bulberg Ridge, located north of the Gamma Substation site and the Horseshoe Ridge located in the south close to the Gamma Substation site. Other ridges and hills in the study area include the Platberg, Nooinberg, Groot and the Tafelberg ridge. There are no ridges located within the proposed 80 m servitude. 6.2 Climatic Conditions Based on the information recorded in the Victoria West area, the average annual rainfall for the Victoria West region is 328 mm. The maximum total rainfall recorded in one day is 131 mm. Average annual rainfall for the De Aar region as recorded at the De Aar weather station is 331,4 mm with a total maximum rainfall recorded in one day of 112 mm. -

Explore the Northern Cape Province

Cultural Guiding - Explore The Northern Cape Province When Schalk van Niekerk traded all his possessions for an 83.5 carat stone owned by the Griqua Shepard, Zwartboy, Sir Richard Southey, Colonial Secretary of the Cape, declared with some justification: “This is the rock on which the future of South Africa will be built.” For us, The Star of South Africa, as the gem became known, shines not in the East, but in the Northern Cape. (Tourism Blueprint, 2006) 2 – WildlifeCampus Cultural Guiding Course – Northern Cape Module # 1 - Province Overview Component # 1 - Northern Cape Province Overview Module # 2 - Cultural Overview Component # 1 - Northern Cape Cultural Overview Module # 3 - Historical Overview Component # 1 - Northern Cape Historical Overview Module # 4 - Wildlife and Nature Conservation Overview Component # 1 - Northern Cape Wildlife and Nature Conservation Overview Module # 5 - Namaqualand Component # 1 - Namaqualand Component # 2 - The Hantam Karoo Component # 3 - Towns along the N14 Component # 4 - Richtersveld Component # 5 - The West Coast Module # 5 - Karoo Region Component # 1 - Introduction to the Karoo and N12 towns Component # 2 - Towns along the N1, N9 and N10 Component # 3 - Other Karoo towns Module # 6 - Diamond Region Component # 1 - Kimberley Component # 2 - Battlefields and towns along the N12 Module # 7 - The Green Kalahari Component # 1 – The Green Kalahari Module # 8 - The Kalahari Component # 1 - Kuruman and towns along the N14 South and R31 Northern Cape Province Overview This course material is the copyrighted intellectual property of WildlifeCampus. It may not be copied, distributed or reproduced in any format whatsoever without the express written permission of WildlifeCampus. 3 – WildlifeCampus Cultural Guiding Course – Northern Cape Module 1 - Component 1 Northern Cape Province Overview Introduction Diamonds certainly put the Northern Cape on the map, but it has far more to offer than these shiny stones. -

Namaqualand and Challenges to the Law Community Resource

•' **• • v ^ WiKSHOr'IMPOLITICIALT ... , , AWD POLICY ANALYSi • ; ' st9K«onTHp^n»< '" •wJ^B^W-'EP.SrTY NAMAQUALAND AND CHALLENGES TO THE LAW: COMMUNITY RESOURCE MANAGEMENT AND LEGAL FRAMEWORKS Henk Smith Land reform in the arid Namaqualand region of South Africa offers unique challenges. Most of the land is owned by large mining companies and white commercial farmers. The government's restitution programme which addresses dispossession under post 1913 Apartheid land laws, will not be the major instrument for land reform in Namaqualand. Most dispossession of indigenous Nama people occurred during the previous century or the State was not directly involved. Redistribution and land acquisition for those in need of land based income opportunities and qualifying for State assistance will to some extent deal with unequal land distribution pattern. Surface use of mining land, and small mining compatible with large-scale mining may provide new opportunities for redistribution purposes. The most dramatic land reform measures in Namaqualand will be in the field of tenure reform, and specifically of communal tenure systems. Namaqualand features eight large reserves (1 200 OOOha covering 25% of the area) set aside for the local communities. These reserves have a history which is unique in South Africa. During the 1800's as the interior of South Africa was being colonised, the rights of Nama descendant communities were recognised through State issued "tickets of occupation". Subsequent legislation designed to administer these exclusively Coloured areas, confirmed that the communities' interests in land predating the legislation. A statutory trust of this sort creates obligations for the State in public law. Furthermore, the new constitution insists on appropriate respect for the fundamental principles of non-discrimination and freedom of movement. -

Namaqua National Park Park Management Plan

Namaqua National Park Park Management Plan For the period 2013 - 2023 Section 1: Authorisation This management plan is hereby internally accepted and authorised as required for managing the Namaqua National Park in terms of Sections 39 and 41 of the National Environmental Management: Protected Areas Act (Act 57 of 2003). NNP MP 2012 - 2023 – i Mr Bernard van Lente Date: 01 November 2012 Park Manager: Namaqua National Park Mr Dries Engelbrecht Date: 01 November 2012 Regional General Manager: Arid Cluster Mr Paul Daphne Date: 01 November 2012 Managing Executive: Parks Dr David Mabunda Chief Executive: SANParks Date: 05 June 2013 NAMAQUA NATIONAL PARK – MANAGEMET PLAN – MANAGEMET PLAN NAMAQUA NATIONAL PARK Mr K.D. Dlamini Date:10 June 2013 Chair: SANParks Board Approved by the Minister of Water and Environment Affairs Mrs B.E. E. Molewa, MP Date: 05 September 2013 Minister of Water and Environment Affairs NNP MP 2012 - 2023 – ii Table of contents No. Index Page 1 Section 1: Authorisations i Table of contents iii Glossary v Acronyms and abbreviations vi Lists of figures, tables and appendices vii Executive summary viii Section 2: Legal status 1 2 Introduction 1 2.1 Name of the area 1 2.2 Location 1 2.3 History of establishment 1 2.4 Contractual agreements 1 2.5 Total area 1 2.6 Highest point 2 2.7 Municipal areas in which the park falls 2 2.8 International, national and provincial listings 2 2.9 Biophysical and socio-economic description 2 2.9.1 Climate 2 2.9.2 Topography 2 2.9.3 Geology and soils 3 2.9.4 Biodiversity 4 2.9.5 Palaeontology, -

FARR Is Dedicated to Building Positive Futures in South African Communities

FARR is dedicated to building positive futures in South African communities PLEASE NOTE: Pictures in this newsletter DO NOT depict children with fetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD), but all children from the communities who participate in FARR’s activities. FARR 2019 1 Dr Leana Olivier Prof Denis Viljoen (CEO) (Chairperson) FARR COLLABORATION By Professor Denis Viljoen Dr Louisa Bhengu (Chairman: FARR Board of Directors) (Board member) The 22nd year of FARR’s existence, like Mr Adrian Botha South Africa, has seen further growth of our (Board member) activities, change in personnel, shifting fo- Board cus in line with natural needs and sadly, a Members fond farewell to Board Members who have Prof Tania Douglas served us so well. So goodbye and sincere (Board member) thanks to Dr Mike Urban who served as a Board Member for close to 10 years. Also hereby welcome to our new Board Member, Prof Marietjie de Villiers. We trust your new position will bring you further personal growth and your expertise will benefit us all richly. I know the following short section will em- barrass our CEO, who has continued to Prof Marietjie De Villiers (Board member) lead FARR so successfully to further new projects, renewal of existing services and broadening our footprint in the goal of mini- Prof JP van Niekerk (Board member) mising and preventing the effects of alcohol abuse especially during pregnancy. Dr Lea- na Olivier has attended several international meetings (Europe & Canada) and has been invited to Australia later this year to share Our some experiences regarding mainly FASD management and prevention. -

Soil Information for Proposed De Aar Solar One Photovoltaic Power Project, Northern Cape

SCOPING REPORT On contract research for CCA Environmental SOIL INFORMATION FOR PROPOSED DE AAR SOLAR ONE PHOTOVOLTAIC POWER PROJECT, NORTHERN CAPE By D.G. Paterson (Pr. Sci. Nat. 400463/04) Report Number GW/A/2012/01 January 2012 ARC-Institute for Soil, Climate and Water, Private Bag X79, Pretoria 0001, South Africa Tel (012) 310 2500 Fax (012) 323 1157 1 DECLARATION This report was prepared by me, DG Paterson of ARC-Institute for Soil Climate. I have an MSc degree in Soil Science from University of Pretoria and have considerable experience in soil studies and agricultural assessments since 1981. I have compiled more than 200 such surveys for a variety of purposes. This specialist report was compiled on behalf of CCA Environmental (Pty) Ltd for their use in undertaking a Scoping and Environmental Impact Assessment process for the proposed De Aar Solar One Photovoltaic Power Project in the Northern Cape Province. I hereby declare that I am qualified to compile this report as a registered Natural Scientist (Reg. No. 400463/04) and that I am independent of any of the parties involved and that I have compiled an impartial report, based solely on all the information available. D G Paterson January 2012 2 DETAILS OF SPECIALIST AND DECLARATION OF INTEREST (For official use only) File Reference Number: 12/12/20/2313 NEAS Reference Number: DEAT/EIA/0000362/2011 Date Received: Application for authorisation in terms of the National Environmental Management Act, 1998 (Act No. 107 of 1998), as amended and the Environmental Impact Assessment Regulations, -

Ncta Map 2017 V4 Print 11.49 MB

here. Encounter martial eagles puffed out against the morning excellent opportunities for river rafting and the best wilderness fly- Stargazers, history boffins and soul searchers will all feel welcome Experience the Northern Cape Northern Cape Routes chill, wildebeest snorting plumes of vapour into the freezing air fishing in South Africa, while the entire Richtersveld is a mountain here. Go succulent sleuthing with a botanical guide or hike the TOURISM INFORMATION We invite you to explore one of our spectacular route and the deep bass rumble of a black- maned lion proclaiming its biker’s dream. Soak up the culture and spend a day following Springbok Klipkoppie for a dose of Anglo-Boer War history, explore NORTHERN CAPE TOURISM AUTHORITY Discover the heart of the Northern Cape as you travel experiences or even enjoy a combination of two or more as territory from a high dune. the footsteps of a traditional goat herder and learn about life of the countless shipwrecks along the coast line or visit Namastat, 15 Villiers Street, Kimberley CBD, 8301 Tel: +27 (0) 53 833 1434 · Fax +27 (0) 53 831 2937 along its many routes and discover a myriad of uniquely di- you travel through our province. the nomads. In the villages, the locals will entertain guests with a traditional matjies-hut village. Just get out there and clear your Traveling in the Kalahari is perfect for the adventure-loving family Email: [email protected] verse experiences. Each of the five regions offers interest- storytelling and traditional Nama step dancing upon request. mind! and adrenaline seekers. -

Download This

TOWN PRODUCT CONTACT ATTRIBUTES ACCOMM CONTACT DETAILS DETAILS STEINKOPF Kookfontein Tel: 027-7218841 *Cultural Tours *Kookfontein 027-7218841 Rondawels Faks: 027-7218842 *Halfmens / Succulent Rondawels – Situated along the N7, E-mail: tours self catering / on about 60 km from [email protected] *Flower tours (during request Springbok on the way flower season) to Vioolsdrif, Cultural/field Calitz *Hiking / walking Steinkopf has a strong Guide 0736357021 tours Nama culture due to *Immanual Centre the strong Nama (Succulent Nursery) history inherited from *Kinderlê (sacred mass the past. grave of 32 Nama children) 24 hr Petrol Station; *Steinkopf High ATM / FNB; Surgery; School Choir (songs in Ambulance Service; Nama, Xhosa, German Shops/Take Aways; and Afrikaans Night Club; Pub; *Klipfontein (old Liquor Stores; Police watertower and Anglo Station. Boere War graves of British soldiers) PORT NOLLOTH Municipal Alta Kotze *Port Nolloth *Bedrock 027-851 8353 Offices 027-8511111 Museum *Guesthouse A small pioneering *Port Nolloth *Scotia Inn Hotel: 027-85 1 8865 harbour town on the Seafarms *Port Indigo Guest 027-851 8012 icy cold Atlantic *Harbour – experience house: Ocean, Port Nolloth is the rich history of the *Mcdougalls Bay 027-8511110 home to diamond coastal area Caravan Park & divers, miners and *Sizamile – a township Chalets fishers with with a rich culture and a *Muisvlak Motel: 027-85 1 8046 fascinatingly diverse long history of struggle *Country Club Flats: 0835555919 cultures. *Historical Roman Catholic Church – Self contained ATM/Banking (FNB) near the beach, one of holiday facilities and Service the oldest buildings accommodation: Station; Surgery; around *Daan deWaal 0825615256 Ambulance; Police *Willem *R. -

Aquifer Vulnerability of South Africa

17° 18° 19° 20° 21° 22° 23° 24° 25° 26° 27° 28° 29° 30° 31° 32° Z I M B A B W E 22° 22° Musina Pafuri Mopane Tshipise Alldays Pundu Maria Swartwater Buysdorp Makhado Thohoyandou Tom Burke Levubu 23° 23° Bochum Elim Shingwedzi Mogwadi Giyani Rebone Vivo-Dendron Ga-Ramokgopa Morebeng Lephalale Mooketsi Aquifer Vulnerability POLOKWANE Tzaneen Bakenberg Mmotong Letsitele Seshego PHALABORWA of Gravellotte Olifants E Mokopane 24° 24° Sentrum Dorpsrivier U South Africa Mookgophong Zebediela Nyl River Valley Penge Hoedspruit B O T S W A N A Mookgophong Ga-Masemola Satara Q Thabazimbi Roedtan I Dwaalboom Modimolle Jane Furse Steelpoort Supingstadt Ohrigstad B Crcodile River Bela-Bela Bushbuckridge Northam Marble Hall Belfast Tloonane Village M Rapotokwane Mashishing Skukuza Siyabuswa Sabie Hazyview Motswedi Ga Mokgatlha Mabeskraal Fafung 25° A 25° Groblersdal Roossenekal Mokgola Bagatla Crocodile River Lehurutshe Soshanguve Z Nossob Moloto Dullstroom Komatipoort Zeerust Swartruggens NELSPRUIT Brits Cullinan Malalane O Ottoshoop Rustenburg Kroondal_Marikana Middelburg PRETORIA Bronkhorstspruit Machadodorp Mata-Mata Pomfret Mafikeng Koster Centurion M Tosca eMalahleni Barberton Bo-Molopo Tarlton Lichtenburg Carolina Badplaas Krugersdorp Kempton Park Piet Plessis Delmas 26° JOHANNESBURG Hendrina 26° Heuningvlei Setlagole Ventersdorp-Eye Ventersdorp Springs Carletonville Background: Coligny Leandra Heidelberg Secunda Implementation of the Reconstruction and Development Programme Twee Rivieren Stella Sannieshof Bethal Ganyesa Ermelo Potchefstroom Amsterdam (RDP) in South Africa has highlighted the importance of groundwater Delareyville Vereeniging Balfour resources in the country as the role they will play in satisfying the targets Sasolburg Greylingstad Morgenzon Rietfontein Ottosdal Klerksdorp SWAZILAND Van Zylsrus Migdol of the RDP. As a result, exploration, development and protection of Vryburg Parys Deneysville Standerton Askham Vredefort aquifers is receiving unprecedented attention. -

Thesis Hum 2010 Bregman Joel.Pdf

Town The copyright of this thesis rests with the University of Cape Town. No quotation from it or information derivedCape from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of theof source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non-commercial research purposes only. University Land and Society in the Komaggas region of Namaqualand Joel Bregman BRGJOE001 A dissertation submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Master of Arts in Historical Studies Faculty of the Humanities University of Cape Town 2010 Town COMPULSORY DECLARATION This work has not been previously submitted in whole,Cape or in part, for the award of any degree. It is my own work. Each significant contribution to, and quotation in, this dissertation from the work, or works, of other people has been attributed, and has been cited and referenced. Of Signature: Date: University Land and Society in the Komaggas region of Namaqualand Joel Bregman (University of Cape Town) Abstract: This paper explores the history of Namaqualand and specifically the Komaggas community. By taking note of the major developments that occurred in the area, the effects on this community over the last 200 or so years have been established. The focal point follows the history of land; its usage, dispossession and importance to the survival of Namaqualanders. Using the records of travellers to the region, the views of government officials, local inhabitants as well as numerous analyses of contemporary authors, a detailed understanding of this area has emerged. Among other things, the research has attempted to ascertain whether the current Komaggas community has a claim to a greater portion of land than it currently holds.