High Altitude Integrated Natural Resource

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

6 the Environments Associated with the Proposed Alternative Sites

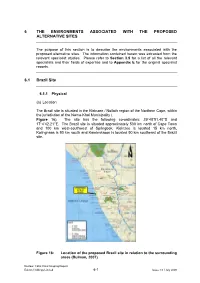

6 THE ENVIRONMENTS ASSOCIATED WITH THE PROPOSED ALTERNATIVE SITES The purpose of this section is to describe the environments associated with the proposed alternative sites. The information contained herein was extracted from the relevant specialist studies. Please refer to Section 3.5 for a list of all the relevant specialists and their fields of expertise and to Appendix E for the original specialist reports. 6.1 Brazil Site 6.1.1 Physical (a) Location The Brazil site is situated in the Kleinzee / Nolloth region of the Northern Cape, within the jurisdiction of the Nama-Khoi Municipality ( Figure 16). The site has the following co-ordinates: 29°48’51.40’’S and 17°4’42.21’’E. The Brazil site is situated approximately 500 km north of Cape Town and 100 km west-southwest of Springbok. Kleinzee is located 15 km north, Koiingnaas is 90 km south and Kamieskroon is located 90 km southeast of the Brazil site. Figure 16: Location of the proposed Brazil site in relation to the surrounding areas (Bulman, 2007) Nuclear 1 EIA: Final Scoping Report Eskom Holdings Limited 6-1 Issue 1.0 / July 2008 (b) Topography The topography in the Brazil region is largely flat, with only a gentle slope down to the coast. The coast is composed of both sandy and rocky shores. The topography is characterised by a small fore-dune complex immediately adjacent to the coast with the highest elevation of approximately nine mamsl. Further inland the general elevation depresses to about five mamsl in the middle of the study area and then gradually rises towards the east. -

Explore the Northern Cape Province

Cultural Guiding - Explore The Northern Cape Province When Schalk van Niekerk traded all his possessions for an 83.5 carat stone owned by the Griqua Shepard, Zwartboy, Sir Richard Southey, Colonial Secretary of the Cape, declared with some justification: “This is the rock on which the future of South Africa will be built.” For us, The Star of South Africa, as the gem became known, shines not in the East, but in the Northern Cape. (Tourism Blueprint, 2006) 2 – WildlifeCampus Cultural Guiding Course – Northern Cape Module # 1 - Province Overview Component # 1 - Northern Cape Province Overview Module # 2 - Cultural Overview Component # 1 - Northern Cape Cultural Overview Module # 3 - Historical Overview Component # 1 - Northern Cape Historical Overview Module # 4 - Wildlife and Nature Conservation Overview Component # 1 - Northern Cape Wildlife and Nature Conservation Overview Module # 5 - Namaqualand Component # 1 - Namaqualand Component # 2 - The Hantam Karoo Component # 3 - Towns along the N14 Component # 4 - Richtersveld Component # 5 - The West Coast Module # 5 - Karoo Region Component # 1 - Introduction to the Karoo and N12 towns Component # 2 - Towns along the N1, N9 and N10 Component # 3 - Other Karoo towns Module # 6 - Diamond Region Component # 1 - Kimberley Component # 2 - Battlefields and towns along the N12 Module # 7 - The Green Kalahari Component # 1 – The Green Kalahari Module # 8 - The Kalahari Component # 1 - Kuruman and towns along the N14 South and R31 Northern Cape Province Overview This course material is the copyrighted intellectual property of WildlifeCampus. It may not be copied, distributed or reproduced in any format whatsoever without the express written permission of WildlifeCampus. 3 – WildlifeCampus Cultural Guiding Course – Northern Cape Module 1 - Component 1 Northern Cape Province Overview Introduction Diamonds certainly put the Northern Cape on the map, but it has far more to offer than these shiny stones. -

Namaqualand and Challenges to the Law Community Resource

•' **• • v ^ WiKSHOr'IMPOLITICIALT ... , , AWD POLICY ANALYSi • ; ' st9K«onTHp^n»< '" •wJ^B^W-'EP.SrTY NAMAQUALAND AND CHALLENGES TO THE LAW: COMMUNITY RESOURCE MANAGEMENT AND LEGAL FRAMEWORKS Henk Smith Land reform in the arid Namaqualand region of South Africa offers unique challenges. Most of the land is owned by large mining companies and white commercial farmers. The government's restitution programme which addresses dispossession under post 1913 Apartheid land laws, will not be the major instrument for land reform in Namaqualand. Most dispossession of indigenous Nama people occurred during the previous century or the State was not directly involved. Redistribution and land acquisition for those in need of land based income opportunities and qualifying for State assistance will to some extent deal with unequal land distribution pattern. Surface use of mining land, and small mining compatible with large-scale mining may provide new opportunities for redistribution purposes. The most dramatic land reform measures in Namaqualand will be in the field of tenure reform, and specifically of communal tenure systems. Namaqualand features eight large reserves (1 200 OOOha covering 25% of the area) set aside for the local communities. These reserves have a history which is unique in South Africa. During the 1800's as the interior of South Africa was being colonised, the rights of Nama descendant communities were recognised through State issued "tickets of occupation". Subsequent legislation designed to administer these exclusively Coloured areas, confirmed that the communities' interests in land predating the legislation. A statutory trust of this sort creates obligations for the State in public law. Furthermore, the new constitution insists on appropriate respect for the fundamental principles of non-discrimination and freedom of movement. -

Climate Variability, Climate Change and Water Resource Strategies for Small Municipalities

Climate variability, climate change and water resource strategies for small municipalities Water resource management strategies in response to climate change in South Africa, drawing on the analysis of coping strategies adopted by vulnerable communities in the Northern Cape province of South Africa in times of climate variability REPORT TO THE WATER RESEARCH COMMISSION P Mukheibir D Sparks University of Cape Town WRC Project: K5/1500 September 2005 Climate variability, climate change and water resource strategies for small municipalities i Executive summary Background and motivation In many parts of the world, variability in climatic conditions is already resulting in wide ranging impacts, especially on water resources and agriculture. Climate variability is already being observed to be increasing, although there remain uncertainties about the link to climate change. However, the link to water management problems is obvious. Water is a limiting resource for development in South Africa and a change in water supply could have major implications in most sectors of the economy, especially in the agriculture sector. Factors that contribute to vulnerability in water systems in southern Africa include seasonal and inter-annual variations in rainfall, which are amplified by high run-off production and evaporation rates. Current modelling scenarios suggest that there will be significant climate change1 impacts in South Africa (Hewitson et al. 2005). Climate change is expected to alter the present hydrological resources in southern Africa and add pressure on the adaptability of future water resources (Schulze & Perks 2000) . During the past 20 years, most of Africa has experienced extensive droughts, the last three being 1986-88, 1991-92 and 1997-98 (after Chenje & Johnson 1996). -

10 Year Report 1

DOCKDA Rural Development Agency: 1994–2004 Celebrating Ten Years of Rural Development DOCKDA 10 year report 1 A Decade of Democracy 2 Globalisation and African Renewal 2 Rural Development in the Context of Globalisation 3 Becoming a Rural Development Agency 6 Organogram 7 Indaba 2002 8 Indaba 2004 8 Monitoring and Evaluation 9 Donor Partners 9 Achievements: 1994–2004 10 Challenges: 1994–2004 11 Namakwa Katolieke Ontwikkeling (Namko) 13 Katolieke Ontwikkeling Oranje Rivier (KOOR) 16 Hopetown Advice and Development Office (HADO) 17 Bisdom van Oudtshoorn Katolieke Ontwikkeling (BOKO) 18 Gariep Development Office (GARDO) 19 Karoo Mobilisasie, Beplanning en Rekonstruksie Organisasie (KAMBRO) 19 Sectoral Grant Making 20 Capacity Building for Organisational Development 27 Early Childhood Development Self-reliance Programme 29 HIV and AIDS Programme 31 2 Ten Years of Rural Development A Decade of Democracy In 1997, DOCKDA, in a publication summarising the work of the organisation in the first three years of The first ten years of the new democracy in South Africa operation, noted that it was hoped that the trickle-down coincided with the celebration of the first ten years approach of GEAR would result in a steady spread of of DOCKDA’s work in the field of rural development. wealth to poor people.1 In reality, though, GEAR has South Africa experienced extensive changes during failed the poor. According to the Human Development this period, some for the better, some not positive at Report 2003, South Africans were poorer in 2003 than all. A central change was the shift, in 1996, from the they were in 1995.2 Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP) to the Growth, Employment and Redistribution Strategy Globalisation and African Renewal (GEAR). -

Thesis Hum 2010 Bregman Joel.Pdf

Town The copyright of this thesis rests with the University of Cape Town. No quotation from it or information derivedCape from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of theof source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non-commercial research purposes only. University Land and Society in the Komaggas region of Namaqualand Joel Bregman BRGJOE001 A dissertation submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Master of Arts in Historical Studies Faculty of the Humanities University of Cape Town 2010 Town COMPULSORY DECLARATION This work has not been previously submitted in whole,Cape or in part, for the award of any degree. It is my own work. Each significant contribution to, and quotation in, this dissertation from the work, or works, of other people has been attributed, and has been cited and referenced. Of Signature: Date: University Land and Society in the Komaggas region of Namaqualand Joel Bregman (University of Cape Town) Abstract: This paper explores the history of Namaqualand and specifically the Komaggas community. By taking note of the major developments that occurred in the area, the effects on this community over the last 200 or so years have been established. The focal point follows the history of land; its usage, dispossession and importance to the survival of Namaqualanders. Using the records of travellers to the region, the views of government officials, local inhabitants as well as numerous analyses of contemporary authors, a detailed understanding of this area has emerged. Among other things, the research has attempted to ascertain whether the current Komaggas community has a claim to a greater portion of land than it currently holds. -

14 Northern Cape Province

Section B:Section Profile B:Northern District HealthCape Province Profiles 14 Northern Cape Province John Taolo Gaetsewe District Municipality (DC45) Overview of the district The John Taolo Gaetsewe District Municipalitya (previously Kgalagadi) is a Category C municipality located in the north of the Northern Cape Province, bordering Botswana in the west. It comprises the three local municipalities of Gamagara, Ga- Segonyana and Joe Morolong, and 186 towns and settlements, of which the majority (80%) are villages. The boundaries of this district were demarcated in 2006 to include the once north-western part of Joe Morolong and Olifantshoek, along with its surrounds, into the Gamagara Local Municipality. It has an established rail network from Sishen South and between Black Rock and Dibeng. It is characterised by a mixture of land uses, of which agriculture and mining are dominant. The district holds potential as a viable tourist destination and has numerous growth opportunities in the industrial sector. Area: 27 322km² Population (2016)b: 238 306 Population density (2016): 8.7 persons per km2 Estimated medical scheme coverage: 14.5% Cities/Towns: Bankhara-Bodulong, Deben, Hotazel, Kathu, Kuruman, Mothibistad, Olifantshoek, Santoy, Van Zylsrus. Main Economic Sectors: Agriculture, mining, retail. Population distribution, local municipality boundaries and health facility locations Source: Mid-Year Population Estimates 2016, Stats SA. a The Local Government Handbook South Africa 2017. A complete guide to municipalities in South Africa. Seventh -

9/10 November 2013 Voting Station List Northern Cape

9/10 November 2013 voting station list Northern Cape Municipality Ward Voting Voting station name Latitude Longitude Address district NC061 - RICHTERSVELD 30601001 65800010VGK CHURCH HALL -28.44504 16.99122KUBOES, KUBOES, KUBOES [Port Nolloth] NC061 - RICHTERSVELD 30601001 65800021 EKSTEENFONTEIN -28.82506 17.254293 RIVER STREET, EKSTEENFONTEIN, NAMAQUALAND [Port Nolloth] COMMUNITY HALL NC061 - RICHTERSVELD 30601001 65800043DIE GROENSAAL -28.12337 16.892578REUNING MINE, SENDELINGSDRIFT, NAMQUALAND [Port Nolloth] NC061 - RICHTERSVELD 30601001 65800054 LEKKERSING COMMUNITY -29.00187 17.099938 223 LINKS STREET, LEKKERSING, MAMAQUALAND [Port Nolloth] HALL NC061 - RICHTERSVELD 30601002 65800032 SANDDRIFT COMMUNITY HALL -28.4124 16.774912 REIERLAAN, SANDDRIFT, NAMAQUALAND [Port Nolloth] NC061 - RICHTERSVELD 30601002 65840014 N ORSMONDSAAL ALEXANDER -28.61245 16.49101 ORANJE ROAD, ALEXANDER BAY, NAMAQUALAND [Port Nolloth] BAY NC061 - RICHTERSVELD 30601003 65790018 SIZAMILE CLINIC HALL -29.25759 16.883425 2374 SIZWE STREET, SIZAMILE, PORT NOLLOTH, [Port Nolloth] NAMAQUALAND NC061 - RICHTERSVELD 30601004 65790029DROP IN CENTRE -29.25985 16.87502516 BURDEN, PORT NOLLOTH, NOLLOTHVILLE [Port Nolloth] NC062 - NAMA KHOI 30602001 65720011 CONCORDIA -29.54402 17.946736 BETHELSTRAAT, CONCORDIA, CONCORDIA [Springbok] GEMEENSKAPSENTRUM NC062 - NAMA KHOI 30602001 65860038GAMOEPSAAL -29.89306 18.416432, , NAMAQUALAND [Springbok] NC062 - NAMA KHOI 30602001 65860061 GAMOEP SAAMTREKSAAL -29.51538 18.313218 , , NAMAQUALAND [Springbok] NC062 - NAMA KHOI 30602002 -

Rooifontein Bulk Water Supply on the Remainder of Leliefontein 614, Kamiesberg Municipality, Northern Cape

1 PALAEONTOLOGICAL HERITAGE COMMENT: ROOIFONTEIN BULK WATER SUPPLY ON THE REMAINDER OF LELIEFONTEIN 614, KAMIESBERG MUNICIPALITY, NORTHERN CAPE John E. Almond PhD (Cantab.) Natura Viva cc, PO Box 12410 Mill Street, Cape Town 8010, RSA [email protected] January 2018 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The overall palaeontological impact significance of the proposed Bulk Water Supply System development on the Remainder of Leliefontein 614 near Rooifontein, Namaqualand klipkoppe region of the Northern Cape, is considered to be LOW. This is because the study area is underlain by unfossiliferous metamorphic basement rocks (granite-gneisses etc) and / or mantled by superficial sediments of low palaeontological sensitivity (e.g. alluvium of the Buffelsrivier), while the development footprint is very small. It is therefore recommended that, pending the exposure of significant new fossils during development, exemption from further specialist palaeontological studies and mitigation be granted for this development. The archaeologist carrying out the field assessment of the study area should report to SAHRA any substantial unmapped areas of alluvial gravels or well-consolidated finer alluvial sediments encountered, since these might contain fossil bones and teeth of mammals. 1. PROJECT OUTLINE The proposed Bulk Water Supply System development on the Remainder of Leliefontein 614 near Rooifontein, Kamiesberg Municipality, Northern Cape involves the following infrastructural components (CTS Heritage 2017; Fig. 1): • Equipment for existing boreholes; • Equipment for additional boreholes; • Construction of a 190 kl steel panel reservoir; • Installation of approximately 6km of pipelines; • Construction of a Water Treatment Works (desalination plant) and associated evaporation ponds (waste brine). 2. GEOLOGICAL CONTEXT The footprint of the proposed Bulk Water Supply System development is situated at c. -

NC Sub Oct2016 N-Portnolloth.Pdf

# # !C # ### # !C^# #!.C# # !C # # # # # # # # # # # ^!C # # # # # # ^ # # ^ # ## # !C ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C# # !C # # # # # # ## # # #!C# # # # !C# # # # ## ^ ## # # !C # # # # ## # # # #!C # # ^ !C # # # #^ # # # # # # ## ## # # #!C# # # # # # # !C# ## !C# # ## # # # # # !C # !C # # # ###^ # # # # # # # # # # # # !C# ## ## # ## # # # # # # # # ## # # # # #!C ## # # # !C# # # # # # # ## # # # # # # # ##!C ## # # ## !C## # # ## # # ## # ##!C# # # !C# # # #^ # # # # # # # # # # ## # # # # # # # ## # ## # # # # #!C ## #!C #!C# ## # # # # # # # # ^ # # ## # # ## # # !C# ^ ## # # # # ## # # # # # # ## # # # # ## # ## # # # # ## ## # # # # !C# # !C # # #!C # # # #!C ## # # # !C## # # # # ## # # # # # # # ## ## # # ### # # # # # ## # # # # # # ## ###!C # ## ## ## # # ## # # # ### ## # # # ^!C# ### # # # # ^ # # # # # ## ## # # # # # #!C # ### # ## #!C## # #!C # # !C # #!C#### # # ## # # # # !C # # # ## # # # ## # # ## # ## # # ## # ## #!C# # # ## # # # # !C# # ####!C## # # !C # # # #!C ## !C# # !.# # ## # # # # # # ## ## #!C # # # # # ## # # # #### # # ## # # # ## # ## # #^# # # # # ^ ## # !C# ## # # # # # # # !C ## # # # ###!C## ##!C# # # # # ## !C# # !C### # # ^ # !C ##### # # !C# ^##!C# # # !C # #!C## ## ## ## #!C # # ## # # ## # # ## # ## !C # # # ## ## #!C # # # # !C # # ^# ### ## ## ## # # # # !C# !.!C## # !C# ##### ## # # # # ## ## ## ### # !C### # # # # ## #!C## # # ## ### ## # # # # ^ # # ## # # # # # # ## !C# # !C ^ ## # # ^ # # # # ## ^ ## ## # # # # # #!C # !C## # #!C # # # ## ## # # # # # # # ## #!C# # !C # # # !C -

Nc Travelguide 2016 1 7.68 MB

Experience Northern CapeSouth Africa NORTHERN CAPE TOURISM AUTHORITY Tel: +27 (0) 53 832 2657 · Fax +27 (0) 53 831 2937 Email:[email protected] www.experiencenortherncape.com 2016 Edition www.experiencenortherncape.com 1 Experience the Northern Cape Majestically covering more Mining for holiday than 360 000 square kilometres accommodation from the world-renowned Kalahari Desert in the ideas? North to the arid plains of the Karoo in the South, the Northern Cape Province of South Africa offers Explore Kimberley’s visitors an unforgettable holiday experience. self-catering accommodation Characterised by its open spaces, friendly people, options at two of our rich history and unique cultural diversity, finest conservation reserves, Rooipoort and this land of the extreme promises an unparalleled Dronfield. tourism destination of extreme nature, real culture and extreme adventure. Call 053 839 4455 to book. The province is easily accessible and served by the Kimberley and Upington airports with daily flights from Johannesburg and Cape Town. ROOIPOORT DRONFIELD Charter options from Windhoek, Activities Activities Victoria Falls and an internal • Game viewing • Game viewing aerial network make the exploration • Bird watching • Bird watching • Bushmen petroglyphs • Vulture hide of all five regions possible. • National Heritage Site • Swimming pool • Self-drive is allowed Accommodation The province is divided into five Rooipoort has a variety of self- Accommodation regions and boasts a total catering accommodation to offer. • 6 fully-equipped • “The Shooting Box” self-catering chalets of six national parks, including sleeps 12 people sharing • Consists of 3 family units two Transfrontier parks crossing • Box Cottage and 3 open plan units sleeps 4 people sharing into world-famous safari • Luxury Tented Camp destinations such as Namibia accommodation andThis Botswanais the world of asOrange well River as Cellars. -

Integrated Development Plan 2012 – 2016

Namakwa District Municipality Integrated Development Plan 2012 – 2016 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Forward: Executive Mayor 3 Forward: Municipal Manager 4 1. BACKGROUND 5 1.1. Introduction 5 2. DISTRICT ANALYSIS AND PROFILE 5 2.1. Municipal Area Analysis 5 2.2. Demographic Analysis 7 2.3. Migration 8 2.4. Economic Analysis 9 2.5. Climate Change 12 2.6. Environmental Management Framework 14 3. NEED ANALYSIS/PRIORITIES BY B-MUNICPALITIES 17 4. STRATEGIC GUIDES AND OBJECTIVES 30 4.1. National 30 4.2. Provincial 34 4.3. District 35 4.4. Institutional Structures 37 5. DEVELOPMENTAL PROJECTS 38 5.1. Priority List per Municipality 46 5.2. Sectoral Projects/Programmes 53 5.3. Five Year Implementation Plan 100 6. APPROVAL 155 7. ANNEXURE 155 Process Plan 2012/2013 - Annexure A 156 2 Forward Executive Mayor 3 Forward Municipal Manager 4 1. BACKGROUND 1.1. Introduction The District Municipality, a category C-Municipality, is obliged to compile an Integrated Development Plan (IDP) for its jurisdiction area, in terms of legislation. This IDP is the third cycle of this process and is for the period 2012-2016. The IDP is a strategic plan to guide the development of the District for the specific period. It guides the planning, budgeting, implementation management and future decision making processes of the municipality. This whole strategic process must be aligned and are subject to all National and Provincial Planning instruments and guidelines (See attached summarized list). The compilation of the IDP is managed through an IDP Steering Committee, which consists of municipal officials, managers of departments and is chaired by the Municipal Manager.