Acocks and Historical Changes in Karoo Biota

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pending World Record Waterbuck Wins Top Honor SC Life Member Susan Stout Has in THIS ISSUE Dbeen Awarded the President’S Cup Letter from the President

DSC NEWSLETTER VOLUME 32,Camp ISSUE 5 TalkJUNE 2019 Pending World Record Waterbuck Wins Top Honor SC Life Member Susan Stout has IN THIS ISSUE Dbeen awarded the President’s Cup Letter from the President .....................1 for her pending world record East African DSC Foundation .....................................2 Defassa Waterbuck. Awards Night Results ...........................4 DSC’s April Monthly Meeting brings Industry News ........................................8 members together to celebrate the annual Chapter News .........................................9 Trophy and Photo Award presentation. Capstick Award ....................................10 This year, there were over 150 entries for Dove Hunt ..............................................12 the Trophy Awards, spanning 22 countries Obituary ..................................................14 and almost 100 different species. Membership Drive ...............................14 As photos of all the entries played Kid Fish ....................................................16 during cocktail hour, the room was Wine Pairing Dinner ............................16 abuzz with stories of all the incredible Traveler’s Advisory ..............................17 adventures experienced – ibex in Spain, Hotel Block for Heritage ....................19 scenic helicopter rides over the Northwest Big Bore Shoot .....................................20 Territories, puku in Zambia. CIC International Conference ..........22 In determining the winners, the judges DSC Publications Update -

Boselaphus Tragocamelus</I>

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln USGS Staff -- Published Research US Geological Survey 2008 Boselaphus tragocamelus (Artiodactyla: Bovidae) David M. Leslie Jr. U.S. Geological Survey, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usgsstaffpub Leslie, David M. Jr., "Boselaphus tragocamelus (Artiodactyla: Bovidae)" (2008). USGS Staff -- Published Research. 723. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usgsstaffpub/723 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the US Geological Survey at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in USGS Staff -- Published Research by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. MAMMALIAN SPECIES 813:1–16 Boselaphus tragocamelus (Artiodactyla: Bovidae) DAVID M. LESLIE,JR. United States Geological Survey, Oklahoma Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit and Department of Natural Resource Ecology and Management, Oklahoma State University, Stillwater, OK 74078-3051, USA; [email protected] Abstract: Boselaphus tragocamelus (Pallas, 1766) is a bovid commonly called the nilgai or blue bull and is Asia’s largest antelope. A sexually dimorphic ungulate of large stature and unique coloration, it is the only species in the genus Boselaphus. It is endemic to peninsular India and small parts of Pakistan and Nepal, has been extirpated from Bangladesh, and has been introduced in the United States (Texas), Mexico, South Africa, and Italy. It prefers open grassland and savannas and locally is a significant agricultural pest in India. It is not of special conservation concern and is well represented in zoos and private collections throughout the world. DOI: 10.1644/813.1. -

6 the Environments Associated with the Proposed Alternative Sites

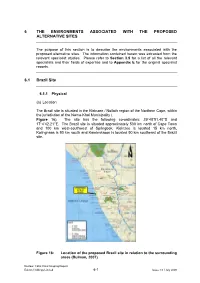

6 THE ENVIRONMENTS ASSOCIATED WITH THE PROPOSED ALTERNATIVE SITES The purpose of this section is to describe the environments associated with the proposed alternative sites. The information contained herein was extracted from the relevant specialist studies. Please refer to Section 3.5 for a list of all the relevant specialists and their fields of expertise and to Appendix E for the original specialist reports. 6.1 Brazil Site 6.1.1 Physical (a) Location The Brazil site is situated in the Kleinzee / Nolloth region of the Northern Cape, within the jurisdiction of the Nama-Khoi Municipality ( Figure 16). The site has the following co-ordinates: 29°48’51.40’’S and 17°4’42.21’’E. The Brazil site is situated approximately 500 km north of Cape Town and 100 km west-southwest of Springbok. Kleinzee is located 15 km north, Koiingnaas is 90 km south and Kamieskroon is located 90 km southeast of the Brazil site. Figure 16: Location of the proposed Brazil site in relation to the surrounding areas (Bulman, 2007) Nuclear 1 EIA: Final Scoping Report Eskom Holdings Limited 6-1 Issue 1.0 / July 2008 (b) Topography The topography in the Brazil region is largely flat, with only a gentle slope down to the coast. The coast is composed of both sandy and rocky shores. The topography is characterised by a small fore-dune complex immediately adjacent to the coast with the highest elevation of approximately nine mamsl. Further inland the general elevation depresses to about five mamsl in the middle of the study area and then gradually rises towards the east. -

Climate Variability, Climate Change and Water Resource Strategies for Small Municipalities

Climate variability, climate change and water resource strategies for small municipalities Water resource management strategies in response to climate change in South Africa, drawing on the analysis of coping strategies adopted by vulnerable communities in the Northern Cape province of South Africa in times of climate variability REPORT TO THE WATER RESEARCH COMMISSION P Mukheibir D Sparks University of Cape Town WRC Project: K5/1500 September 2005 Climate variability, climate change and water resource strategies for small municipalities i Executive summary Background and motivation In many parts of the world, variability in climatic conditions is already resulting in wide ranging impacts, especially on water resources and agriculture. Climate variability is already being observed to be increasing, although there remain uncertainties about the link to climate change. However, the link to water management problems is obvious. Water is a limiting resource for development in South Africa and a change in water supply could have major implications in most sectors of the economy, especially in the agriculture sector. Factors that contribute to vulnerability in water systems in southern Africa include seasonal and inter-annual variations in rainfall, which are amplified by high run-off production and evaporation rates. Current modelling scenarios suggest that there will be significant climate change1 impacts in South Africa (Hewitson et al. 2005). Climate change is expected to alter the present hydrological resources in southern Africa and add pressure on the adaptability of future water resources (Schulze & Perks 2000) . During the past 20 years, most of Africa has experienced extensive droughts, the last three being 1986-88, 1991-92 and 1997-98 (after Chenje & Johnson 1996). -

Animals of Africa

Silver 49 Bronze 26 Gold 59 Copper 17 Animals of Africa _______________________________________________Diamond 80 PYGMY ANTELOPES Klipspringer Common oribi Haggard oribi Gold 59 Bronze 26 Silver 49 Copper 17 Bronze 26 Silver 49 Gold 61 Copper 17 Diamond 80 Diamond 80 Steenbok 1 234 5 _______________________________________________ _______________________________________________ Cape grysbok BIG CATS LECHWE, KOB, PUKU Sharpe grysbok African lion 1 2 2 2 Common lechwe Livingstone suni African leopard***** Kafue Flats lechwe East African suni African cheetah***** _______________________________________________ Red lechwe Royal antelope SMALL CATS & AFRICAN CIVET Black lechwe Bates pygmy antelope Serval Nile lechwe 1 1 2 2 4 _______________________________________________ Caracal 2 White-eared kob DIK-DIKS African wild cat Uganda kob Salt dik-dik African golden cat CentralAfrican kob Harar dik-dik 1 2 2 African civet _______________________________________________ Western kob (Buffon) Guenther dik-dik HYENAS Puku Kirk dik-dik Spotted hyena 1 1 1 _______________________________________________ Damara dik-dik REEDBUCKS & RHEBOK Brown hyena Phillips dik-dik Common reedbuck _______________________________________________ _______________________________________________African striped hyena Eastern bohor reedbuck BUSH DUIKERS THICK-SKINNED GAME Abyssinian bohor reedbuck Southern bush duiker _______________________________________________African elephant 1 1 1 Sudan bohor reedbuck Angolan bush duiker (closed) 1 122 2 Black rhinoceros** *** Nigerian -

9/10 November 2013 Voting Station List Northern Cape

9/10 November 2013 voting station list Northern Cape Municipality Ward Voting Voting station name Latitude Longitude Address district NC061 - RICHTERSVELD 30601001 65800010VGK CHURCH HALL -28.44504 16.99122KUBOES, KUBOES, KUBOES [Port Nolloth] NC061 - RICHTERSVELD 30601001 65800021 EKSTEENFONTEIN -28.82506 17.254293 RIVER STREET, EKSTEENFONTEIN, NAMAQUALAND [Port Nolloth] COMMUNITY HALL NC061 - RICHTERSVELD 30601001 65800043DIE GROENSAAL -28.12337 16.892578REUNING MINE, SENDELINGSDRIFT, NAMQUALAND [Port Nolloth] NC061 - RICHTERSVELD 30601001 65800054 LEKKERSING COMMUNITY -29.00187 17.099938 223 LINKS STREET, LEKKERSING, MAMAQUALAND [Port Nolloth] HALL NC061 - RICHTERSVELD 30601002 65800032 SANDDRIFT COMMUNITY HALL -28.4124 16.774912 REIERLAAN, SANDDRIFT, NAMAQUALAND [Port Nolloth] NC061 - RICHTERSVELD 30601002 65840014 N ORSMONDSAAL ALEXANDER -28.61245 16.49101 ORANJE ROAD, ALEXANDER BAY, NAMAQUALAND [Port Nolloth] BAY NC061 - RICHTERSVELD 30601003 65790018 SIZAMILE CLINIC HALL -29.25759 16.883425 2374 SIZWE STREET, SIZAMILE, PORT NOLLOTH, [Port Nolloth] NAMAQUALAND NC061 - RICHTERSVELD 30601004 65790029DROP IN CENTRE -29.25985 16.87502516 BURDEN, PORT NOLLOTH, NOLLOTHVILLE [Port Nolloth] NC062 - NAMA KHOI 30602001 65720011 CONCORDIA -29.54402 17.946736 BETHELSTRAAT, CONCORDIA, CONCORDIA [Springbok] GEMEENSKAPSENTRUM NC062 - NAMA KHOI 30602001 65860038GAMOEPSAAL -29.89306 18.416432, , NAMAQUALAND [Springbok] NC062 - NAMA KHOI 30602001 65860061 GAMOEP SAAMTREKSAAL -29.51538 18.313218 , , NAMAQUALAND [Springbok] NC062 - NAMA KHOI 30602002 -

Rooifontein Bulk Water Supply on the Remainder of Leliefontein 614, Kamiesberg Municipality, Northern Cape

1 PALAEONTOLOGICAL HERITAGE COMMENT: ROOIFONTEIN BULK WATER SUPPLY ON THE REMAINDER OF LELIEFONTEIN 614, KAMIESBERG MUNICIPALITY, NORTHERN CAPE John E. Almond PhD (Cantab.) Natura Viva cc, PO Box 12410 Mill Street, Cape Town 8010, RSA [email protected] January 2018 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The overall palaeontological impact significance of the proposed Bulk Water Supply System development on the Remainder of Leliefontein 614 near Rooifontein, Namaqualand klipkoppe region of the Northern Cape, is considered to be LOW. This is because the study area is underlain by unfossiliferous metamorphic basement rocks (granite-gneisses etc) and / or mantled by superficial sediments of low palaeontological sensitivity (e.g. alluvium of the Buffelsrivier), while the development footprint is very small. It is therefore recommended that, pending the exposure of significant new fossils during development, exemption from further specialist palaeontological studies and mitigation be granted for this development. The archaeologist carrying out the field assessment of the study area should report to SAHRA any substantial unmapped areas of alluvial gravels or well-consolidated finer alluvial sediments encountered, since these might contain fossil bones and teeth of mammals. 1. PROJECT OUTLINE The proposed Bulk Water Supply System development on the Remainder of Leliefontein 614 near Rooifontein, Kamiesberg Municipality, Northern Cape involves the following infrastructural components (CTS Heritage 2017; Fig. 1): • Equipment for existing boreholes; • Equipment for additional boreholes; • Construction of a 190 kl steel panel reservoir; • Installation of approximately 6km of pipelines; • Construction of a Water Treatment Works (desalination plant) and associated evaporation ponds (waste brine). 2. GEOLOGICAL CONTEXT The footprint of the proposed Bulk Water Supply System development is situated at c. -

Chapter 15 the Mammals of Angola

Chapter 15 The Mammals of Angola Pedro Beja, Pedro Vaz Pinto, Luís Veríssimo, Elena Bersacola, Ezequiel Fabiano, Jorge M. Palmeirim, Ara Monadjem, Pedro Monterroso, Magdalena S. Svensson, and Peter John Taylor Abstract Scientific investigations on the mammals of Angola started over 150 years ago, but information remains scarce and scattered, with only one recent published account. Here we provide a synthesis of the mammals of Angola based on a thorough survey of primary and grey literature, as well as recent unpublished records. We present a short history of mammal research, and provide brief information on each species known to occur in the country. Particular attention is given to endemic and near endemic species. We also provide a zoogeographic outline and information on the conservation of Angolan mammals. We found confirmed records for 291 native species, most of which from the orders Rodentia (85), Chiroptera (73), Carnivora (39), and Cetartiodactyla (33). There is a large number of endemic and near endemic species, most of which are rodents or bats. The large diversity of species is favoured by the wide P. Beja (*) CIBIO-InBIO, Centro de Investigação em Biodiversidade e Recursos Genéticos, Universidade do Porto, Vairão, Portugal CEABN-InBio, Centro de Ecologia Aplicada “Professor Baeta Neves”, Instituto Superior de Agronomia, Universidade de Lisboa, Lisboa, Portugal e-mail: [email protected] P. Vaz Pinto Fundação Kissama, Luanda, Angola CIBIO-InBIO, Centro de Investigação em Biodiversidade e Recursos Genéticos, Universidade do Porto, Campus de Vairão, Vairão, Portugal e-mail: [email protected] L. Veríssimo Fundação Kissama, Luanda, Angola e-mail: [email protected] E. -

Brochure Highlight Those Impressive Russia

2019 44 years and counting The products and services listed Join us on Facebook, follow us on Instagram or visit our web site to become one Table of Contents in advertisements are offered and of our growing number of friends who receive regular email updates on conditions Alaska . 4 provided solely by the advertiser. and special big game hunt bargains. Australia . 38 www.facebook.com/NealAndBrownleeLLC Neal and Brownlee, L.L.C. offers Austria . 35 Instagram: @NealAndBrownleeLLC no guarantees, warranties or Azerbaijan . 31 recommendations for the services or Benin . 18 products offered. If you have questions Cameroon . 19 related to these services, please contact Canada . 6 the advertiser. Congo . 20 All prices, terms and conditions Continental U .S . 12 are, to the best of our knowledge at the Ethiopia . 20 time of printing, the most recent and Fishing Alaska . 42 accurate. Prices, terms and conditions Fishing British Columbia . 41 are subject to change without notice Fishing New Zealand . 42 due to circumstances beyond our Kyrgyzstan . 31 control. Jeff C. Neal Greg Brownlee Trey Sperring Mexico . 14 Adventure travel and big game 2018 was another fantastic year for our company thanks to the outfitters we epresentr and the Mongolia . 32 hunting contain inherent risks and clients who trusted us. We saw more clients traveling last season than in any season in the past, Mozambique . 21 dangers by their very nature that with outstanding results across the globe. African hunting remained strong, with our primary Namibia . 22 are beyond the control of Neal and areas producing outstanding success across several countries. Asian hunting has continued to be Nepal . -

List of 28 Orders, 129 Families, 598 Genera and 1121 Species in Mammal Images Library 31 December 2013

What the American Society of Mammalogists has in the images library LIST OF 28 ORDERS, 129 FAMILIES, 598 GENERA AND 1121 SPECIES IN MAMMAL IMAGES LIBRARY 31 DECEMBER 2013 AFROSORICIDA (5 genera, 5 species) – golden moles and tenrecs CHRYSOCHLORIDAE - golden moles Chrysospalax villosus - Rough-haired Golden Mole TENRECIDAE - tenrecs 1. Echinops telfairi - Lesser Hedgehog Tenrec 2. Hemicentetes semispinosus – Lowland Streaked Tenrec 3. Microgale dobsoni - Dobson’s Shrew Tenrec 4. Tenrec ecaudatus – Tailless Tenrec ARTIODACTYLA (83 genera, 142 species) – paraxonic (mostly even-toed) ungulates ANTILOCAPRIDAE - pronghorns Antilocapra americana - Pronghorn BOVIDAE (46 genera) - cattle, sheep, goats, and antelopes 1. Addax nasomaculatus - Addax 2. Aepyceros melampus - Impala 3. Alcelaphus buselaphus - Hartebeest 4. Alcelaphus caama – Red Hartebeest 5. Ammotragus lervia - Barbary Sheep 6. Antidorcas marsupialis - Springbok 7. Antilope cervicapra – Blackbuck 8. Beatragus hunter – Hunter’s Hartebeest 9. Bison bison - American Bison 10. Bison bonasus - European Bison 11. Bos frontalis - Gaur 12. Bos javanicus - Banteng 13. Bos taurus -Auroch 14. Boselaphus tragocamelus - Nilgai 15. Bubalus bubalis - Water Buffalo 16. Bubalus depressicornis - Anoa 17. Bubalus quarlesi - Mountain Anoa 18. Budorcas taxicolor - Takin 19. Capra caucasica - Tur 20. Capra falconeri - Markhor 21. Capra hircus - Goat 22. Capra nubiana – Nubian Ibex 23. Capra pyrenaica – Spanish Ibex 24. Capricornis crispus – Japanese Serow 25. Cephalophus jentinki - Jentink's Duiker 26. Cephalophus natalensis – Red Duiker 1 What the American Society of Mammalogists has in the images library 27. Cephalophus niger – Black Duiker 28. Cephalophus rufilatus – Red-flanked Duiker 29. Cephalophus silvicultor - Yellow-backed Duiker 30. Cephalophus zebra - Zebra Duiker 31. Connochaetes gnou - Black Wildebeest 32. Connochaetes taurinus - Blue Wildebeest 33. Damaliscus korrigum – Topi 34. -

High Altitude Integrated Natural Resource

DEAD OR ALIVE? HUMAN RIGHTS AND LAND REFORM IN NAMAQUALAND COMMONS, SOUTH AFRICA PAPER PRESENTED AT THE BIENNUAL CONFERENCE OF THE INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR THE STUDY OF COMMON PROPERTY, ‘THE COMMONS IN AN AGE OF GLOBALISATION’, VICTORIA FALLS, ZIMBABWE, JUNE 2002 POUL WISBORG1 MARCH 2002 1 PhD Research Fellow, Centre for International Environment and Development Studies, Noragric, Agricultural University of Norway and Programme for Land and Agrarian Studies (PLAAS), School of Government, University of Western Cape, Bellville, South Africa Abstract Dead or alive? Human rights and land reform in Namaqualand commons, South Africa Land tenure is emerging as a controversial human rights issue in both local resource conflicts and globalised rhetoric. While access to land is not a human right according to international law, many tenets concerning the right to food and a secure livelihood, to redress for past violations, to rule of law, non-discrimination and democracy apply to land governance. The relevance of the human rights talk for development is contested. Harri Englund’s notion of “the dead hand of human rights” refers to the gaps between global and local discourses. Land, particularly the commons, may be a problematic human rights issue because local idioms of ownership are embedded, elusive and flexible, and therefore difficult to codify and protect by national or international regimes. Furthermore, the economic pressures of globalisation may contradict civil-political rights and opportunities, leading Upendra Baxi to discuss whether and how there is a ‘future for human rights’. Based on fieldwork in two communal areas, the paper examines rights perceptions in a process of reforming communal land governance in Namaqualand, South Africa. -

1. the Historic Copper Mine Route

4. The Pilgrimage Route On this route tourists can visit several churches and missionary stations in the Namakwa area that were established by the Rhenish Mission Society, 1. The Historic Copper Mine Route the London Mission Society, the Church of England, the Roman Catholic Church, the Methodist Church, the Jewish Society and many other church This is a self-drive tour through the region’s historic copper mining towns. The copper mining history dates back to 1685 when Simon van der organisations. These church organisations established both churches and schools in the area and contributed greatly to education and religion in the 7. The Museum Route Stel’s search for gold led him to discover copper at Carolusberg. Commercial copper mining commenced in 1852 and drew to a close in 2004. area. The pastors in charge of these churches also assisted in the negotiations for land and other rights for the local communities. The museums exhibit the historical and cultural lifestyles of the people of the area. The detailed exhibits and information keep tourists occupied for hours. The Okiep Copper Company (OCC), or “Jan Komponie” as the locals referred to it, was once a well-known industry leader in the copper mining We trust that you will be inspired by the relics and remains of the past decades which strived to preserve and develop religion in our communities. sector. This route will take you on a journey through Carolusberg, Springbok, Concordia, Okiep, Alexander Bay, Hondeklip Bay and Nababeep. Town Tourist Attractions We trust that your copper mining town experience will be one to remember.