The Cholas: Some Enduring Issues of Statecraft, Military Matters and International Relations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Mahabharata

^«/4 •m ^1 m^m^ The original of tiiis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924071123131 ) THE MAHABHARATA OF KlUSHNA-DWAIPAYANA VTASA TRANSLATED INTO ENGLISH PROSE. Published and distributed, chiefly gratis, BY PROTSP CHANDRA EOY. BHISHMA PARVA. CALCUTTA i BHiRATA PRESS. No, 1, Raja Gooroo Dass' Stbeet, Beadon Square, 1887. ( The righi of trmsMm is resem^. NOTICE. Having completed the Udyoga Parva I enter the Bhishma. The preparations being completed, the battle must begin. But how dan- gerous is the prospect ahead ? How many of those that were counted on the eve of the terrible conflict lived to see the overthrow of the great Knru captain ? To a KsJtatriya warrior, however, the fiercest in- cidents of battle, instead of being appalling, served only as tests of bravery that opened Heaven's gates to him. It was this belief that supported the most insignificant of combatants fighting on foot when they rushed against Bhishma, presenting their breasts to the celestial weapons shot by him, like insects rushing on a blazing fire. I am not a Kshatriya. The prespect of battle, therefore, cannot be unappalling or welcome to me. On the other hand, I frankly own that it is appall- ing. If I receive support, that support may encourage me. I am no Garuda that I would spurn the strength of number* when battling against difficulties. I am no Arjuna conscious of superhuman energy and aided by Kecava himself so that I may eHcounter any odds. -

Stamps of India Army Postal Covers (APO)

E-Book - 22. Checklist - Stamps of India Army Postal Covers (A.P.O) By Prem Pues Kumar [email protected] 9029057890 For HOBBY PROMOTION E-BOOKS SERIES - 22. FREE DISTRIBUTION ONLY DO NOT ALTER ANY DATA ISBN - 1st Edition Year - 8th May 2020 [email protected] Prem Pues Kumar 9029057890 Page 1 of 27 Nos. Date/Year Details of Issue 1 2 1971 - 1980 1 01/12/1954 International Control Commission - Indo-China 2 15/01/1962 United Nations Force - Congo 3 15/01/1965 United Nations Emergency Force - Gaza 4 15/01/1965 International Control Commission - Indo-China 5 02/10/1968 International Control Commission - Indo-China 6 15.01.1971 Army Day 7 01.04.1971 Air Force Day 8 01.04.1971 Army Educational Corps 9 04.12.1972 Navy Day 10 15.10.1973 The Corps of Electrical and Mechanical Engineers 11 15.10.1973 Zojila Day, 7th Light Cavalary 12 08.12.1973 Army Service Corps 13 28.01.1974 Institution of Military Engineers, Corps of Engineers Day 14 16.05.1974 Directorate General Armed Forces Medical Services 15 15.01.1975 Armed Forces School of Nursing 03.11.1976 Winners of PVC-1 : Maj. Somnath Sharma, PVC (1923-1947), 4th Bn. The Kumaon 16 Regiment 17 18.07.1977 Winners of PVC-2: CHM Piru Singh, PVC (1916 - 1948), 6th Bn, The Rajputana Rifles. 18 20.10.1977 Battle Honours of The Madras Sappers Head Quarters Madras Engineer Group & Centre 19 21.11.1977 The Parachute Regiment 20 06.02.1978 Winners of PVC-3: Nk. -

ARMED FORCES TRIBUNAL, REGIONAL BENCH, KOCHI O.A No.205 of 2013 CORAM: APPLICANT

ARMED FORCES TRIBUNAL, REGIONAL BENCH, KOCHI O.A No.205 OF 2013 FRIDAY, THE 20TH DAY OF JUNE, 2014/30TH JYAISHTA, 1936 CORAM: HON'BLE MR. JUSTICE SHRIKANT TRIPATHI, MEMBER (J) HON'BLE VICE ADMIRAL M.P.MURALIDHARAN, AVSM & BAR, NM, MEMBER(A) APPLICANT:- NO.2619339 M EX-SEPOY JUSTIN GEORGE, 27 MADRAS REGIMENT, AGED 21 YEARS, S/O. SHRI CHACKO VARKEY, VAYALILL HOUSE, ELAMAKAD PO., KOTTAYAM DISTRICT, KERALA STATE – 686 514. BY ADV. SHRI. RAMESH.C.R. versus RESPONDENTS: 1. THE UNION OF INDIA, THROUGH THE SECRETARY, MINISTRY OF DEFENCE (ARMY), SOUTH BLOCK, NEW DELHI – 110 001. 2. THE CHIEF OF ARMY STAFF, DHQ PO., INTEGRATED HQRS., MINISTRY OF DEFENCE, SOUTH BLOCK, NEW DELHI – 110 011. 3. THE ADJUTANT GENERAL, AG'S BRANCH, ARMY HEADQUARTERS, DHQ PO., NEW DELHI -110 011. 4. THE OIC., RECORDS, THE MADRAS REGT., WELLINGTON, TAMIL NADU – 643 231. 5. THE COMMANDING OFFICER, 27 MADRAS, C/O 56 APO, PIN- 911 427. BY ADV. SRI. P.J.PHIILIP, CENTRAL GOVT. COUNSEL. O.A. No.205 of 2013 - 2 - ORDER Shrikant Tripathi, Member (J): 1. Heard Mr.Ramesh C.R. for the applicant and Mr.P.J.Philip for the respondents and perused the record. 2. The applicant, EX-SEPOY JUSTIN GEORGE, NO.2619339 M has challenged his discharge from the Army and has prayed for his re- instatement in service with full benefits of pay and allowances. He was enrolled in the Indian Army as a Soldier on 18th March 2011. While he was posted to 27th Madras Regiment, he applied for discharge under Army Rule 13 (3) III (iv), which was allowed. -

(GS) BYJU's Classes: 9980837187 1. Ans C Topic

1. Ans C Topic- Current affairs Difficulty level-Moderate Type-Factual Explanation: ZED Scheme aims to rate and handhold all MSMEs to deliver top quality products using clean technology. It will have sector-specific parameters for each industry. MSME sector is crucial for the economic progress of India and this scheme will help to match global quality control standards. The slogan of Zero Defect, Zero Effect (ZED) was first mentioned by PM Narendra Modi in his Independence Day speech in 2014. It was given for producing high quality manufacturing products with a minimal negative impact on environment 2. Anc C Topic- Current affairs Difficulty level-Moderate Type-Factual Explanation: Union Government has launched Mining Surveillance System (MSS), a pan-India surveillance network to check illegal mining using latest satellite technology. MSS is a satellite-based monitoring system which aims to check illegal mining activity through automatic remote-sensing detection technology in order to establish a regime of responsive mineral administration. In the MSS, Khasra maps of mining leases have been geo-referenced and are superimposed on latest satellite remote sensing scenes obtained from CARTOSAT & USGS. 3. Ans D Topic: Ancient History - Inscriptions Type: Factual Level: Medium Explanation: The Allahabad pillar is an Ashoka Stambha, one of the pillars of Ashoka, an emperor of the Maurya dynasty who reigned in the 3rd century BCE. While it is one of the few extant pillars that carry his edicts, it is particularly notable for containing later inscriptions attributed to the Gupta emperor, Samudragupta (4th century CE). Also engraved on the stone are inscriptions by the Mughal emperor, Jahangir, from the 17th century. -

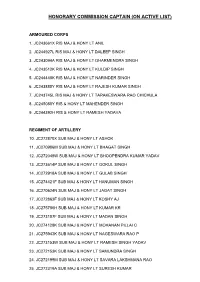

Honorary Commission Captain (On Active List)

HONORARY COMMISSION CAPTAIN (ON ACTIVE LIST) ARMOURED CORPS 1. JC243661X RIS MAJ & HONY LT ANIL 2. JC244927L RIS MAJ & HONY LT DALEEP SINGH 3. JC243094A RIS MAJ & HONY LT DHARMENDRA SINGH 4. JC243512K RIS MAJ & HONY LT KULDIP SINGH 5. JC244448K RIS MAJ & HONY LT NARINDER SINGH 6. JC243880Y RIS MAJ & HONY LT RAJESH KUMAR SINGH 7. JC243745L RIS MAJ & HONY LT TARAKESWARA RAO CHICHULA 8. JC245080Y RIS & HONY LT MAHENDER SINGH 9. JC244392H RIS & HONY LT RAMESH YADAVA REGIMENT OF ARTILLERY 10. JC272870X SUB MAJ & HONY LT ASHOK 11. JC270906M SUB MAJ & HONY LT BHAGAT SINGH 12. JC272049W SUB MAJ & HONY LT BHOOPENDRA KUMAR YADAV 13. JC273614P SUB MAJ & HONY LT GOKUL SINGH 14. JC272918A SUB MAJ & HONY LT GULAB SINGH 15. JC274421F SUB MAJ & HONY LT HANUMAN SINGH 16. JC270624N SUB MAJ & HONY LT JAGAT SINGH 17. JC272863F SUB MAJ & HONY LT KOSHY AJ 18. JC275786H SUB MAJ & HONY LT KUMAR KR 19. JC273107F SUB MAJ & HONY LT MADAN SINGH 20. JC274128K SUB MAJ & HONY LT MOHANAN PILLAI C 21. JC275943K SUB MAJ & HONY LT NAGESWARA RAO P 22. JC273153W SUB MAJ & HONY LT RAMESH SINGH YADAV 23. JC272153K SUB MAJ & HONY LT SAMUNDRA SINGH 24. JC272199M SUB MAJ & HONY LT SAVARA LAKSHMANA RAO 25. JC272319A SUB MAJ & HONY LT SURESH KUMAR 26. JC273919P SUB MAJ & HONY LT VIRENDER SINGH 27. JC271942K SUB MAJ & HONY LT VIRENDER SINGH 28. JC279081N SUB & HONY LT DHARMENDRA SINGH RATHORE 29. JC277689K SUB & HONY LT KAMBALA SREENIVASULU 30. JC277386P SUB & HONY LT PURUSHOTTAM PANDEY 31. JC279539M SUB & HONY LT RAMESH KUMAR SUBUDHI 32. -

1 Component-I (A) – Personal Details

Component-I (A) – Personal details: 1 Component-I (B) – Description of module: Subject Name Indian Culture Paper Name Outlines of Indian History Module Name/Title South Indian kingdoms : pallavas and chalukyas Module Id I C/ OIH/ 15 Political developments in South India after Pre-requisites Satavavahana and Sangam age To study the Political and Cultural history of South Objectives India under Pallava and Chalukyan periods Keywords Pallava / Kanchi / Chalukya / Badami E-text (Quadrant-I) 1. Introduction The period from C.300 CE to 750 CE marks the second historical phase in the regions south of the Vindhyas. In the first phase we notice the ascendency of the Satavahanas over the Deccan and that of the Sangam Age Kingdoms in Southern Tamilnadu. In these areas and also in Vidarbha from 3rd Century to 6th Century CE there arose about two dozen states which are known to us from their land charters. In Northern Maharashtra and Vidarbha (Berar) the Satavahanas were succeeded by the Vakatakas. Their political history is of more importance to the North India than the South India. But culturally the Vakataka kingdom became a channel for transmitting Brahmanical ideas and social institutions to the South. The Vakataka power was followed by that of the Chalukyas of Badami who played an important role in the history of the Deccan and South India for about two centuries until 753 CE when they were overthrown by their feudatories, the Rashtrakutas. The eastern part of the Satavahana Kingdom, the Deltas of the Krishna and the Godavari had been conquered by the Ikshvaku dynasty in the 3rd Century CE. -

Indian History - Dynasties #4

TISS GK Preparation | Indian History - Dynasties #4 TISS GK Preparation Series: GK is a very important section for TISS especially since the verbal and the quant sections are relatively easy. Hence, getting a good score in GK can easily be the difference between getting a TISS call and not getting one. To help you ace this section, we are starting a series of articles devoted to topics commonly asked in the TISS GK section. We hope that this will help you in your preparation. Every article will also be available in PDF format. Here is our #4 article in this series: Indian History – Dynasties. Indian History is a very important topic for TISS with a lot of questions asked on dynasties, ancient India, etc. To help you, we have compiled a list of the important dynasties of India with a little detail on each. Also, this has been presented in a chronological order. Sr. Dynasty/Empire Detail No. 1 Magadha The core of this kingdom was the area of Bihar south of the Ganges; its first capital was Rajagriha (modern Rajgir) then Pataliputra (modern Patna). Magadha played an important role in the development of Jainism and Buddhism, and two of India's greatest empires, the Maurya Empire and Gupta Empire, originated from Magadha. 2 Maurya The Maurya Empire (322–185 BCE) was the first empire to unify India into one state, and was the largest on the Indian subcontinent. The empire was established by Chandragupta Maurya in Magadha (in modern Bihar) when he overthrew the Nanda Dynasty. Chandragupta's son Bindusara succeeded to the throne around 297 BC. -

University of Oklahoma Graduate College Is

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE IS GANGAIKONDA CHOLAPURAM BUILT BASED ON VAASTU SASTRA? A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE IN ARCHITECTURE By Ramya Palani Norman, Oklahoma 2019 IS GANGAIKONDA CHOLAPURAM BUILT BASED ON VAASTU SASTRA? A THESIS APPROVED FOR THE CHRISTOPHER C. GIBBS COLLEGE OF ARCHITECTURE BY THE COMMITTEE CONSISTING OF Callahan, Marjorie P., Chair Warnken, Charles G. Fithian, Lee A. ©Copyright by RAMYA PALANI 2019 All Rights Reserved. iv Abstract The Cholas (848 CE – 1279 CE) established an imperial line and united a large portion of what is now South India under their rule. The Cholas, known worldwide for their bronze sculptures, world heritage temples and land reforms, were also able builders. They followed a traditional systematic approach called Vaastu Sastra in building their cities, towns, and villages. In an attempt to discover and reconstruct Gangaikonda Cholapuram, an administrative capital (metropolis) of the Chola Dynasty, evidence is collected from the fragments of living inscriptions, epigraphs, archaeological excavation, secondary sources, and other sources pertinent to Vaastu Sastra. The research combines archival research methodology, archaeological documentation and informal architectural survey. The consolidation, analysis, and manipulation of data helps to uncover the urban infrastructure of Gangaikonda Cholapuram city. Keywords: Chola, Cola, South India, Vaastu Shastra, Gangaikonda Cholapuram, Medieval period, -

I Year Dkh11 : History of Tamilnadu Upto 1967 A.D

M.A. HISTORY - I YEAR DKH11 : HISTORY OF TAMILNADU UPTO 1967 A.D. SYLLABUS Unit - I Introduction : Influence of Geography and Topography on the History of Tamil Nadu - Sources of Tamil Nadu History - Races and Tribes - Pre-history of Tamil Nadu. SangamPeriod : Chronology of the Sangam - Early Pandyas – Administration, Economy, Trade and Commerce - Society - Religion - Art and Architecture. Unit - II The Kalabhras - The Early Pallavas, Origin - First Pandyan Empire - Later PallavasMahendravarma and Narasimhavarman, Pallava’s Administration, Society, Religion, Literature, Art and Architecture. The CholaEmpire : The Imperial Cholas and the Chalukya Cholas, Administration, Society, Education and Literature. Second PandyanEmpire : Political History, Administration, Social Life, Art and Architecture. Unit - III Madurai Sultanate - Tamil Nadu under Vijayanagar Ruler : Administration and Society, Economy, Trade and Commerce, Religion, Art and Architecture - Battle of Talikota 1565 - Kumarakampana’s expedition to Tamil Nadu. Nayakas of Madurai - ViswanathaNayak, MuthuVirappaNayak, TirumalaNayak, Mangammal, Meenakshi. Nayakas of Tanjore :SevappaNayak, RaghunathaNayak, VijayaRaghavaNayak. Nayak of Jingi : VaiyappaTubakiKrishnappa, Krishnappa I, Krishnappa II, Nayak Administration, Life of the people - Culture, Art and Architecture. The Setupatis of Ramanathapuram - Marathas of Tanjore - Ekoji, Serfoji, Tukoji, Serfoji II, Sivaji III - The Europeans in Tamil Nadu. Unit - IV Tamil Nadu under the Nawabs of Arcot - The Carnatic Wars, Administration under the Nawabs - The Mysoreans in Tamil Nadu - The Poligari System - The South Indian Rebellion - The Vellore Mutini- The Land Revenue Administration and Famine Policy - Education under the Company - Growth of Language and Literature in 19th and 20th centuries - Organization of Judiciary - Self Respect Movement. Unit - V Tamil Nadu in Freedom Struggle - Tamil Nadu under Rajaji and Kamaraj - Growth of Education - Anti Hindi & Agitation. -

Yonas and Yavanas in Indian Literature Yonas and Yavanas in Indian Literature

YONAS AND YAVANAS IN INDIAN LITERATURE YONAS AND YAVANAS IN INDIAN LITERATURE KLAUS KARTTUNEN Studia Orientalia 116 YONAS AND YAVANAS IN INDIAN LITERATURE KLAUS KARTTUNEN Helsinki 2015 Yonas and Yavanas in Indian Literature Klaus Karttunen Studia Orientalia, vol. 116 Copyright © 2015 by the Finnish Oriental Society Editor Lotta Aunio Co-Editor Sari Nieminen Advisory Editorial Board Axel Fleisch (African Studies) Jaakko Hämeen-Anttila (Arabic and Islamic Studies) Tapani Harviainen (Semitic Studies) Arvi Hurskainen (African Studies) Juha Janhunen (Altaic and East Asian Studies) Hannu Juusola (Middle Eastern and Semitic Studies) Klaus Karttunen (South Asian Studies) Kaj Öhrnberg (Arabic and Islamic Studies) Heikki Palva (Arabic Linguistics) Asko Parpola (South Asian Studies) Simo Parpola (Assyriology) Rein Raud (Japanese Studies) Saana Svärd (Assyriology) Jaana Toivari-Viitala (Egyptology) Typesetting Lotta Aunio ISSN 0039-3282 ISBN 978-951-9380-88-9 Juvenes Print – Suomen Yliopistopaino Oy Tampere 2015 CONTENTS PREFACE .......................................................................................................... XV PART I: REFERENCES IN TEXTS A. EPIC AND CLASSICAL SANSKRIT ..................................................................... 3 1. Epics ....................................................................................................................3 Mahābhārata .........................................................................................................3 Rāmāyaṇa ............................................................................................................25 -

The Panchayat System Under the Cholas Studies from Inscriptions

Historical Research Letter www.iiste.org ISSN 2224-3178 (Paper) ISSN 2225-0964 (Online) Vol.16, 2015 The Panchayat System under the Cholas Studies from Inscriptions R. Marimuth Ph.D,Research Scholar, P.G & Research Department of History, Arignar Anna Govt Arts College, Musiri.- 621 211. INTRODUCTION The Chola kingdom of the sangam period extended from modern Trichy to southern Andhra Pradesh. There capital was first located at Uraiyur and then shifted to Tanjore the history of Cholas falls in the four period the early Cholas the interregnum period medieval Cholas and Chalukya. The Kingdom is very ancient there have been references made in Mahabharata and even in Asokan inscriptions. Among the early Chola rulers mentioned in the Sangam to literature the most marked is Karikala. 1 He is credited with constructing a Dam on the River of Kaveri. It is considered to be earliest dam in the country he carved out an Independent kingdom of his own towards the end of the second century. In ancient Tamil Nadu all the activity were done systematically. In all matters such as administrating the village. Demaracating land boundaries, maintenance the temples they took care that the rules and customs were strictly adhered. Stone inscription written in the Pallavas greater characters commerce from this period. A fact which suggests that with the conquest of chaunisam the Pallavas must have erected their dominion further south of Kanchi into the Cholas Country land adopted the administration with Sanskrit language later stone inscription. A large number of stone inscriptions and copper plate grants are the pillars of in constructing the history of medieval Cholas. -

Economic and Cultural History of Tamilnadu from Sangam Age to 1800 C.E

I - M.A. HISTORY Code No. 18KP1HO3 SOCIO – ECONOMIC AND CULTURAL HISTORY OF TAMILNADU FROM SANGAM AGE TO 1800 C.E. UNIT – I Sources The Literay Sources Sangam Period The consisted, of Tolkappiyam a Tamil grammar work, eight Anthologies (Ettutogai), the ten poems (Padinen kell kanakku ) the twin epics, Silappadikaram and Manimekalai and other poems. The sangam works dealt with the aharm and puram life of the people. To collect various information regarding politics, society, religion and economy of the sangam period, these works are useful. The sangam works were secular in character. Kallabhra period The religious works such as Tamil Navalar Charital,Periyapuranam and Yapperumkalam were religious oriented, they served little purpose. Pallava Period Devaram, written by Apper, simdarar and Sambandar gave references tot eh socio economic and the religious activities of the Pallava age. The religious oriented Nalayira Tivya Prabandam also provided materials to know the relation of the Pallavas with the contemporary rulers of South India. The Nandikkalambakam of Nandivarman III and Bharatavenba of Perumdevanar give a clear account of the political activities of Nandivarman III. The early pandya period Limited Tamil sources are available for the study of the early Pandyas. The Pandikkovai, the Periyapuranam, the Divya Suri Carita and the Guruparamparai throw light on the study of the Pandyas. The Chola Period The chola empire under Vijayalaya and his successors witnessed one of the progressive periods of literary and religious revival in south India The works of South Indian Vishnavism arranged by Nambi Andar Nambi provide amble information about the domination of Hindu religion in south India.