Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scorses by Ebert

Scorsese by Ebert other books by An Illini Century roger ebert A Kiss Is Still a Kiss Two Weeks in the Midday Sun: A Cannes Notebook Behind the Phantom’s Mask Roger Ebert’s Little Movie Glossary Roger Ebert’s Movie Home Companion annually 1986–1993 Roger Ebert’s Video Companion annually 1994–1998 Roger Ebert’s Movie Yearbook annually 1999– Questions for the Movie Answer Man Roger Ebert’s Book of Film: An Anthology Ebert’s Bigger Little Movie Glossary I Hated, Hated, Hated This Movie The Great Movies The Great Movies II Awake in the Dark: The Best of Roger Ebert Your Movie Sucks Roger Ebert’s Four-Star Reviews 1967–2007 With Daniel Curley The Perfect London Walk With Gene Siskel The Future of the Movies: Interviews with Martin Scorsese, Steven Spielberg, and George Lucas DVD Commentary Tracks Beyond the Valley of the Dolls Casablanca Citizen Kane Crumb Dark City Floating Weeds Roger Ebert Scorsese by Ebert foreword by Martin Scorsese the university of chicago press Chicago and London Roger Ebert is the Pulitzer The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 Prize–winning film critic of the Chicago The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London Sun-Times. Starting in 1975, he cohosted © 2008 by The Ebert Company, Ltd. a long-running weekly movie-review Foreword © 2008 by The University of Chicago Press program on television, first with Gene All rights reserved. Published 2008 Siskel and then with Richard Roeper. He Printed in the United States of America is the author of numerous books on film, including The Great Movies, The Great 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 09 08 1 2 3 4 5 Movies II, and Awake in the Dark: The Best of Roger Ebert, the last published by the ISBN-13: 978-0-226-18202-5 (cloth) University of Chicago Press. -

Famous People from Michigan

APPENDIX E Famo[ People fom Michigan any nationally or internationally known people were born or have made Mtheir home in Michigan. BUSINESS AND PHILANTHROPY William Agee John F. Dodge Henry Joy John Jacob Astor Herbert H. Dow John Harvey Kellogg Anna Sutherland Bissell Max DuPre Will K. Kellogg Michael Blumenthal William C. Durant Charles Kettering William E. Boeing Georgia Emery Sebastian S. Kresge Walter Briggs John Fetzer Madeline LaFramboise David Dunbar Buick Frederic Fisher Henry M. Leland William Austin Burt Max Fisher Elijah McCoy Roy Chapin David Gerber Charles S. Mott Louis Chevrolet Edsel Ford Charles Nash Walter P. Chrysler Henry Ford Ransom E. Olds James Couzens Henry Ford II Charles W. Post Keith Crain Barry Gordy Alfred P. Sloan Henry Crapo Charles H. Hackley Peter Stroh William Crapo Joseph L. Hudson Alfred Taubman Mary Cunningham George M. Humphrey William E. Upjohn Harlow H. Curtice Lee Iacocca Jay Van Andel John DeLorean Mike Illitch Charles E. Wilson Richard DeVos Rick Inatome John Ziegler Horace E. Dodge Robert Ingersol ARTS AND LETTERS Mitch Albom Milton Brooks Marguerite Lofft DeAngeli Harriette Simpson Arnow Ken Burns Meindert DeJong W. H. Auden Semyon Bychkov John Dewey Liberty Hyde Bailey Alexander Calder Antal Dorati Ray Stannard Baker Will Carleton Alden Dow (pen: David Grayson) Jim Cash Sexton Ehrling L. Frank Baum (Charles) Bruce Catton Richard Ellmann Harry Bertoia Elizabeth Margaret Jack Epps, Jr. William Bolcom Chandler Edna Ferber Carrie Jacobs Bond Manny Crisostomo Phillip Fike Lilian Jackson Braun James Oliver Curwood 398 MICHIGAN IN BRIEF APPENDIX E: FAMOUS PEOPLE FROM MICHIGAN Marshall Fredericks Hugie Lee-Smith Carl M. -

Newsletter 09/08 DIGITAL EDITION Nr

ISSN 1610-2606 ISSN 1610-2606 newsletter 09/08 DIGITAL EDITION Nr. 229 - Mai 2008 Michael J. Fox Christopher Lloyd LASER HOTLINE - Inh. Dipl.-Ing. (FH) Wolfram Hannemann, MBKS - Talstr. 3 - 70825 K o r n t a l Fon: 0711-832188 - Fax: 0711-8380518 - E-Mail: [email protected] - Web: www.laserhotline.de Newsletter 09/08 (Nr. 229) Mai 2008 editorial Hallo Laserdisc- und DVD-Fans, Technik gehuldigt. Und das mit sehr Saga, dem sei gesagt, dass es keinen liebe Filmfreunde! gut erhaltenen Technicolor-Kopien mit entsprechenden Beitrag im Blog geben Wann war es das letzte Mal, dass Sie 4-Kanal stereophonischem Magnetton. wird. Denn leider beschränkt sich der Stars wie Marilyn Monroe oder Erroll Wer die Western, Komödien, Sandalen- deutsche Filmverleiher auf Pressevor- Flynn in voller CinemaScope-Breite auf schinken und Ritterfilme aus dieser führungen in Frankfurt und München. einer riesigen Leinwand bestaunen Zeit nur vom kleinformatigen TV- Und das auch nur in deutscher Syn- durften? Wenn überhaupt, dann dürfte Schirm her kennt, der kann sich hier chronisation. Schade eigentlich. Aber das schon viele, viele Jahre zurücklie- sozusagen “live” ein Bild davon ma- anschauen werden wir uns den Herrn gen. Ein Grund mehr, dass Sie sich jetzt chen, wie intensiver doch das Film- mit Hut und Peitsche natürlich trotz- auf ein Wiedersehen der nostalgischen erlebnis im Kino wirkt. Das komplette dem – in digitaler Projektion und engli- Art freuen dürfen. Denn am 7. und 8. Programm mit allen Details finden Sie scher Originalfassung in der badischen Juni 2008 veranstaltet die Karlsruher ab Seite 3 in diesem Newsletter. Hauptstadt. Schauburg ein ungewöhnliches Filmfe- stival. -

N° 222 Nous Collaborons Avec: Ééditodito 3

dduu 2233 aavrilvril aauu 6 mmaiai ccinéiné mmusiqueusique eexposxpos tthéatrehéatre ddanseanse wwwwww..journalventilo.journalventilo.ffrr ttousous lleses 1155 jjoursours ggratuitratuit N° 222 Nous collaborons avec: ééditodito 3 CContrOleontrOle dd’identité’identité TAPAGE NOCTURNE L’islam a mauvaise presse. Un rappeur avisé met à 2001 dans une ambiance délétère qu’exploitent l’entrée menaçante de la Turquie en Europe. Une profi t ce malheureux désamour en distribuant avec tous les marchands de peur. En 2005, un journal telle bassesse fi nit par échauffer les esprits. Ce son album un T-shirt malicieusement siglé : « I’m danois de droite provoque l’opinion publique week-end, une mosquée a été incendiée. Quinze muslim, don’t panik » (1). L’affl igeante mésaventure des pays musulmans en publiant les médiocres jours avant, c’était un cimetière musulman qui de ce petit garçon prénommé Islam donne encore caricatures du prophète Mahomet. Le Pape fustige était saccagé. Nicolas Sarkozy a dénoncé un acte à réfl échir. Pour le faire participer à son jeu télévisé l’année d’après, dans un discours à l’université relevant du « racisme le plus inadmissible qui soit ». favori sur la chaîne de télévision pour enfants Gulli, de Ratisbonne en Allemagne, un islam violent. Plutôt que d’imaginer un racisme plus admissible, les responsables du programme ont demandé à ses Une élection présidentielle se pointe en 2007 ? on peut légitimement s’inquiéter de l’apparition de parents de changer son prénom à l’antenne car, On voit fl eurir dans les boîtes aux lettres les pires ces actes odieux. Jusqu’où ira la vague anti-islam ? leur a-t-on expliqué, « il faut que vous compreniez slogans sur « l’islamisation de la France » ou Jusqu’à la guerre des civilisations tant redoutée ? que le nom de votre enfant fait référence Dans un discours d’août 2007 aux à une religion que les Français n’aiment Ambassadeurs de France, le président pas beaucoup. -

METOO Movement, Guillotine Justice and the Law of Sexual Harassment

#METOO Movement, Guillotine Justice and the Law of Sexual Harassment Presented by: Soma Ray‐Ellis, Chair Employment Law Group Prepared with the assistance of Madelena Viksne February 6, 2018 CP24 with Nathan Downer 2 We Were Weinsteined… Not just a man, he has become a movement… 3 Since Weinstein… 120 men (and counting) have been accused including… Accused Position # of Accusations Consequence Harvey Weinstein Movie Producer 57 Fired James Toback Screenwriter and producer 300+ None Ben Affleck Actor and director 1 None Chris Savino Nickelodeon animator 12+ Fired Roy Price CEO Amazon 1 Quit after leave Matt Zimmerman NBC News booker Multiple Fired Josh Besh Celebrity chef 25+ Resigned Mark Halperin Journalist 12 Fired Gilbert Rozon Just For Laughs 9 Resigned 4 Since Weinstein… Accused Position # of Accusations Consequence Jeremy Piven Actor 3 None Dustin Hoffman Actor 1 None Kevin Spacey Actor 24 Fired, show & movie dropped, police Brett Ratner Director 6 None Hamilton Fish President, The New Multiple Resigned Republic Nick Carter Backstreet Boys 1 None Richard Dreyfus Actor 1 None Tom Sizemore Actor 1 None 5 Since Weinstein… Accused Position # of Accusations Consequence Louis C.K. Comedian 5 Netflix special & movie cancelled Larry Nassar National Team Doctor US 3+ Pleaded guilty, Gymnastics faces 25 years in prison _ additional criminal charges, 125 civil lawsuits Oliver Stone Director 2 None Danny Masterson Actor 3 None Andrew Kreisberg Showrunner “Arrow” and 19 Suspended “Supergirl” Charlie Rose PBS and CBS host Multiple None Matt Lauer The Today Show Multiple Fired James Franco Actor 5+ None 6 Dirty Politics… Accused Position # of Accusations Consequence Patrick Brown Ex‐head of the Conservative 2Resigned Party George W. -

Brochures, Props, Advertising Material and Scripts

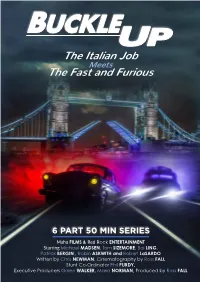

BUCKLE UP The Italian Job Meets The Fast and Furious 6 PART 50 MIN SERIES Maha FILMS & Red Rock ENTERTAINMENT Starring Michael MADSEN, Tom SIZEMORE, Bai LING, Patrick BERGIN , Robin ASKWITH and Robert LaSARDO Written by Chris NEWMAN, Cinematography by Ross FALL Stunt Co-Ordinator Phil PURDY, Executive Producers Galen WALKER, Maria NORMAN, Produced by Ross FALL Buckle Up 1 DISCLAIMER: Red Rock Entertainment Ltd is not authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA). The content of this promotion is not authorised under the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (FSMA). Reliance on the promotion for the purpose of engaging in any investment activity may expose an individual to a significant risk of losing all of the investment. UK residents wishing to participate in this promotion must fall into the category of sophisticated investor or high net worth individual as outlined by the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA). BUCKLE UP CONTENTS 4 Concept 5 Synopsis 6 | 7 Series Bible 8 | 15 Cast 16 Director 17 Production 18 | 19 Executive Producers 21 | 22 Perks & Benefits 22 Equity THE CONCEPT The idea came about when brother arranges to buy the Star Like the film The Warriors, Elgar the writer Chris Newman was of Africa on the black market has to make it back from where watching the 1979 film The from an Arab Prince. He sends a he steals the diamond to the Warriors where a New York courier to pick up the diamond younger brother but this time gang had to make it back to necklace. Unknown to him his it’s Cornwall and the destination Coney Island from Manhattan brother has also learned about is London and it’s got to be after a charismatic gang leader the diamond but he doesn’t done in 8 hours. -

Readily Admits) That Was Provoked by a Growing Interest in the Female Sex

Martin Scorsese’s Divine Comedy Also available from Bloomsbury: The Bloomsbury Companion to Religion and Film, edited by William L. Blizek Dante’s Sacred Poem, Sheila J. Nayar The Sacred and the Cinema, Sheila J. Nayar Martin Scorsese’s Divine Comedy Movies and Religion Catherine O’Brien BLOOMSBURY ACADEMIC Bloomsbury Publishing Plc 50 Bedford Square, London, WC1B 3DP, UK 1385 Broadway, New York, NY 10018, USA BLOOMSBURY and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published in Great Britain 2018 Copyright © Catherine O'Brien, 2018 Catherine O'Brien has asserted her right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as Author of this work. For legal purposes the Acknowledgements on p. vi constitute an extension of this copyright page. Cover design by Catherine Wood Cover image © Appian Way / Paramount / Rex Shutterstock All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: O’Brien, Catherine, 1962- author. Title: Martin Scorsese’s divine comedy: movies and religion / Catherine O’Brien. Description: London; New York, NY : Bloomsbury Academic, 2018. | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Includes filmography. Identifiers: LCCN 2017051481| -

South East West Midwest

NC State (12) Arizona St. (10) Kansas St. (9) Kentucky (8) Texas (7) Massachusetts (6) Saint Louis (5) Louisville (4) Duke (3) Michigan (2) Wichita St. (1) Florida (1) Kansas (2) Syracuse (3) UCLA (4) VCU (5) Ohio St. (6) New Mexico (7) Colorado (8) Pittsburgh (9) Stanford (10) 1. Zach Galifianakis, 1. Jimmy Kimmel, 1. Eric Stonestreet, 1. Ashley Judd, 1. Walter Cronkite, 1. Bill Cosby, 1. Enrique Bolaños, 1. Diane Sawyer, 1. Richard Nixon, 37th 1. Gerald Ford, 38th 1. Riley Pitts, Medal 1. Marco Rubio, U.S. 1. Alf Landon, former 1. Ted Koppel, TV 1. Jim Morrison, 1. Patch Adams, 1. Dwight Yoakam, 1. Penny Marshall, 1. Robert Redford, 1. Gene Kelly, 1. Herbert Hoover, actor, "The Hangover" host, "Jimmy Kimmel actor, "Modern Family" actress, "Kiss the Girls" former anchorman, actor/comedian, "The former president of news anchor President of the U.S. President of the U.S. of Honor recipient Senator, Florida Kansas governor, 1936 journalist, "Nightline" musician, The Doors doctor/social activist country music director/producer, "A actor, “Butch Cassidy actor/dancer/singer, 31st President of the 2. John Tesh, TV Live!" 2. Kirstie Alley, 2. Mitch McConnell, CBS Evening News Cosby Show" Nicaragua 2. Sue Grafton, 2. Charlie Rose, 2. James Earl Jones, 2. Shirley Knight, 2. Bob Graham, presidential candidate 2. Dick Clark, 2. Francis Ford 2. Debbie singer-songwriter League of Their Own" and the Sundance Kid” "Singin' in the Rain" U.S. composer 2. Kate Spade, actress, "Cheers" U.S. Senator, Kentucky 2. Matthew 2. Richard Gere, actor, 2. Robert Guillaume, author, “A is for Alibi” talk-show host, actor, "The Great actress, "The Dark at former U.S. -

Pdf, 393.18 KB

Note: This show periodically replaces their ad breaks with new promotional clips. Because of this, both the transcription for the clips and the timestamps after them may be inaccurate at the time of viewing this transcript 00:00:00 Music Music “Flight of the Intruder: The Bomb Run,” composed by Basil Poledouris from the Flight of the Intruder soundtrack. Dramatic military drums and brass against symphonic background plays in background of dialogue. 00:00:04 Adam Host I was up late flipping the channels the other night, which is the best Pranica time for a local PBS station to put on their premium shit. If you’re lucky, you’ll get that Alone in the Wilderness show about Dick Proenneke and the sledding wolverines, or a mini-marathon of Joy of Painting, which is just the perfect way to fall asleep. And sometimes, one of a treasure trove of classic concert films. Now I know I present myself as the very hip and “now” host of Friendly Fire, but I’ll have you know that my musical interests have always been before my time. The very first concert I ever went to was Jimmy Page and Robert Plant at the Tacoma Dome, the giant concert venue with the acoustics of a shipping container south of Seattle. I was in middle school and let me tell you: wearing that concert T-shirt the next day did not have the “making me cool” effect that I had hoped for. Except with the teachers, which—as you could guess—had the opposite effect. -

LOIS BURWELL Make-Up Artist IATSE 706 Dual Citizenship: US and UK

LOIS BURWELL Make-Up Artist IATSE 706 Dual Citizenship: US and UK FILM WEST SIDE STORY Department Head Director: Steven Spielberg BOOK CLUB Personal Make-Up Artist to Diane Keaton Director: Bill Holderman HOTEL ARTEMIS Personal Make-Up Artist to Jodie Foster Director: Drew Pearce READY PLAYER ONE Department Head Director: Steven Spielberg THE BFG Department Head Director: Steven Spielberg Cast: Mark Rylance, Penelope Wilton LINCOLN Department Head Director: Steven Spielberg Cast: Daniel Day-Lewis, Tommy Lee Jones, Hal Holbrook, David Strathairn, Jared Harris Nominee: BAFTA Best Make-Up & Hair Nominee: Critics’ Choice Award for Best Make-Up WAR HORSE Department Head Director: Steven Spielberg Cast: Emily Watson, Benedict Cumberbatch, Tom Hiddleston LIONS FOR LAMBS Personal Make-Up Artist to Tom Cruise Director: Robert Redford Cast: Tom Cruise WAR OF THE WORLDS Department Head & Personal Make-Up Artist to Tom Cruise Director: Steven Spielberg Cast: Tom Cruise, Dakota Fanning COLLATERAL Personal Make-Up Artist to Tom Cruise Director: Michael Mann THE LAST SAMURAI Department Head & Personal Make-Up Artist to Tom Cruise Director: Ed Zwick Cast: Tom Cruise, William Atherton, Billy Connolly, Timothy Spall Nominee: Hollywood Make-Up Artist Guild Award for Period Make-Up CATCH ME IF YOU CAN Department Head Director: Steven Spielberg THE MILTON AGENCY Lois Burwell 6715 Hollywood Blvd #206, Los Angeles, CA 90028 Make-Up Telephone: 323.466.4441 Facsimile: 323.460.4442 IATSE 706 [email protected] www.miltonagency.com Page 1 of 4 Cast: Amy -

Ali Cherkaoui – First Assistant Director

ALI CHERKAOUI – FIRST ASSISTANT DIRECTOR DGA Member (Southern California Qualification List : UPM) AFAR Member cell fr : + 33 6 17 33 11 00 — cell us : +1 415 425 1558 — cell ma : +212 6 61 74 63 80 www.alitronics.com — [email protected] — skype : ‘alitronics‘ Talent Agency Agency for the Performing Arts (APA) - 405 S Beverly Dr. - Beverly Hills, CA 90212 - USA +1 (310) 888 4200 phone / +1 (310) 888 4242 fax / production.apa-agency.com Representative : Julian SAVODIVKER : +1 (310) 888 4256 - [email protected] - FIRST ASSISTANT DIRECTOR - THE LAST DUEL (Feature) directed by Ridley SCOTT January/March 2020 : First Assistant-Director : France Produced by : (us) / PENINSULA FILM ROYAL ICE (fr) Cast : Matt DAMON, Adam DRIVER, Jodie COMER, Ben AFFLECK… Prep & Shoot in Dordogne, Occitanie, Bourgogne - France GUNPOWDER MILKSHAKE (Feature) directed by Navot PAPUSHADO March/ August 2019 : First Assistant-Director Produced by : THE PICTURE COMPANY (us) / STUDIOCANAL (uk) / STUDIO BABELSBERG (de) Cast : Karen GILLIAN, Lena HEADEY, Chloe COLEMAN, Angela BASSET, Michel YEOH, Carla GUGINO, Paul GIAMATTI Prep & Shoot in Berlin, Germany THE SPY (TV Series in 6 Episodes - Netflix / OCS ) directed by Gideon RAFF January / August 2018 : First Assistant-Director Produced by : LEGENDE FILMS / NETFLIX / OCS Cast : Sacha BARON COHEN, Noah EMMERICH, Hadar RATZON ROTEM, Alexander SIDDIG, Nassim LYES Prep & Shoot in Morocco ( Fes, Azrou & Casablanca) and Budapest, Hungary THE BREITNER COMMANDO (QU’UN SANG IMPUR..) (Feature) directed by Abdel-Raouf -

1. Movies and Memorials

1. Movies and Memorials At the most basic level of shared content, prestige combat films—hereafter PCFs—tell stories of US soldiers fighting abroad in actual historical con- flicts. (United 93 [2006] and Letters from Iwo Jima [2006] are the excep- tions.) Feature films about the American Civil War, which lack a foreign other, and fantasies of American forces at war with imagined enemies (for example the alien invaders of Independence Day [1996]) are excluded. Likewise excluded are movies that depict the US military in a fantastical context, such as Rambo: First Blood, Part Two (1985), which returns to Vietnam to rescue POWs and, in the words of John Rambo, “win this time,” and Top Gun (1986), which elides entirely the dire seriousness that would have attended a dogfight between American F-14s and Communist MiGs in the 1980s and instead celebrates winning, as Christian Appy aptly notes, “a fictional battle in an unknown place against a nameless enemy with no significant cause at stake.”1 PCF narratives engage seriously with historical fact—in only a few cases by way of highly stylized storytelling—and insert the viewer, assumed to be an adult, into a complex context. As the director Oliver Stone said, hopefully, of Platoon (1986) two years after its release: “It became an antidote to Top Gun and Rambo.”2 This complex context, however, is limited in scope. Nearly every PCF represents the battlefield from the point of view of the individual soldier, frequently from the lowest rank: the grunt. Central characters in these films seldom rise above lieutenant (with leading roles in Saving Private Ryan [1998], Band of Brothers [2001], We Were Soldiers [2002], and Green Zone [2010] notable exceptions).