Scorses by Ebert

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Honorable Mentions Movies- LIST 1

The Honorable mentions Movies- LIST 1: 1. A Dog's Life by Charlie Chaplin (1918) 2. Gone with the Wind Victor Fleming, George Cukor, Sam Wood (1940) 3. Sunset Boulevard by Billy Wilder (1950) 4. On the Waterfront by Elia Kazan (1954) 5. Through the Glass Darkly by Ingmar Bergman (1961) 6. La Notte by Michelangelo Antonioni (1961) 7. An Autumn Afternoon by Yasujirō Ozu (1962) 8. From Russia with Love by Terence Young (1963) 9. Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors by Sergei Parajanov (1965) 10. Stolen Kisses by François Truffaut (1968) 11. The Godfather Part II by Francis Ford Coppola (1974) 12. The Mirror by Andrei Tarkovsky (1975) 13. 1900 by Bernardo Bertolucci (1976) 14. Sophie's Choice by Alan J. Pakula (1982) 15. Nostalghia by Andrei Tarkovsky (1983) 16. Paris, Texas by Wim Wenders (1984) 17. The Color Purple by Steven Spielberg (1985) 18. The Last Emperor by Bernardo Bertolucci (1987) 19. Where Is the Friend's Home? by Abbas Kiarostami (1987) 20. My Neighbor Totoro by Hayao Miyazaki (1988) 21. The Sheltering Sky by Bernardo Bertolucci (1990) 22. The Decalogue by Krzysztof Kieślowski (1990) 23. The Silence of the Lambs by Jonathan Demme (1991) 24. Three Colors: Red by Krzysztof Kieślowski (1994) 25. Legends of the Fall by Edward Zwick (1994) 26. The English Patient by Anthony Minghella (1996) 27. Lost highway by David Lynch (1997) 28. Life Is Beautiful by Roberto Benigni (1997) 29. Magnolia by Paul Thomas Anderson (1999) 30. Malèna by Giuseppe Tornatore (2000) 31. Gladiator by Ridley Scott (2000) 32. The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring by Peter Jackson (2001) 33. -

HOLLYWOOD – the Big Five Production Distribution Exhibition

HOLLYWOOD – The Big Five Production Distribution Exhibition Paramount MGM 20th Century – Fox Warner Bros RKO Hollywood Oligopoly • Big 5 control first run theaters • Theater chains regional • Theaters required 100+ films/year • Big 5 share films to fill screens • Little 3 supply “B” films Hollywood Major • Producer Distributor Exhibitor • Distribution & Exhibition New York based • New York HQ determines budget, type & quantity of films Hollywood Studio • Hollywood production lots, backlots & ranches • Studio Boss • Head of Production • Story Dept Hollywood Star • Star System • Long Term Option Contract • Publicity Dept Paramount • Adolph Zukor • 1912- Famous Players • 1914- Hodkinson & Paramount • 1916– FP & Paramount merge • Producer Jesse Lasky • Director Cecil B. DeMille • Pickford, Fairbanks, Valentino • 1933- Receivership • 1936-1964 Pres.Barney Balaban • Studio Boss Y. Frank Freeman • 1966- Gulf & Western Paramount Theaters • Chicago, mid West • South • New England • Canada • Paramount Studios: Hollywood Paramount Directors Ernst Lubitsch 1892-1947 • 1926 So This Is Paris (WB) • 1929 The Love Parade • 1932 One Hour With You • 1932 Trouble in Paradise • 1933 Design for Living • 1939 Ninotchka (MGM) • 1940 The Shop Around the Corner (MGM Cecil B. DeMille 1881-1959 • 1914 THE SQUAW MAN • 1915 THE CHEAT • 1920 WHY CHANGE YOUR WIFE • 1923 THE 10 COMMANDMENTS • 1927 KING OF KINGS • 1934 CLEOPATRA • 1949 SAMSON & DELILAH • 1952 THE GREATEST SHOW ON EARTH • 1955 THE 10 COMMANDMENTS Paramount Directors Josef von Sternberg 1894-1969 • 1927 -

Evaluating Agreement and Disagreement Among Movie Reviewers Alan Agresti & Larry Winner Version of Record First Published: 20 Sep 2012

This article was downloaded by: [University of Florida] On: 08 October 2012, At: 16:45 Publisher: Taylor & Francis Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK CHANCE Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ucha20 Evaluating Agreement and Disagreement among Movie Reviewers Alan Agresti & Larry Winner Version of record first published: 20 Sep 2012. To cite this article: Alan Agresti & Larry Winner (1997): Evaluating Agreement and Disagreement among Movie Reviewers, CHANCE, 10:2, 10-14 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09332480.1997.10542015 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae, and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand, or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with -

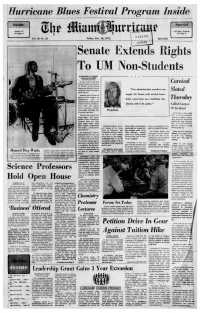

Senate Extends Rights to UM Non-Students

Hurricane Blues Festival Program Inside Inside Special Suntan U? UM Blues Festival see page 4 tyqs fcw see Page 6 Vol. 48 No. 27 Friday, Feb. 16, 1973 284-4401 Senate Extends Rights To UM Non-Students By MICHAEL A. PARKER * * * And CHUCK GOMEZ Of The Hurricana Stall A move which could lead Carnival to more student participation on faculty decision-making boards was finalized Monday "Now administrative members can by Student Body Government Slated (SBG) senators. supply the Senate with needed knou> Senators voted in favor of giving a faculty member, an administrator and an ledge concerning any conflicting leg Thursday employe seats on the student Senate. The three representa islation with V.M. policy.** Called Largest tives would have regular Senate privileges including Of Its Kind voting rights and being able Poepelman to propose legislation. "Carni-Gras," a three-night "We felt they should have UM student -sponsored voting rights," said Senate carnival of games, conces speaker Kevin Poeppelman, sions, rides and educational "because there are often exhibits will open Thursday, many issues which would Feb. 22 on the intramural affect student relationships Presently students sit on during which some Senators tatives are expected to be se field and continue through with faculty, administration such boards as the Union complained that seating fac ated by the end of February. Saturday, Feb. 24. and employes." Board of Governors and ulty members would not in Dr. William Butler, vice Hours are 7 to 11:30 p.m., But Poeppelman told the Rathskeller Advisory Board, effect guarantee students but there is little campus president for student affairs, Thursday and Friday and 1 Hurricane that the move was could sit on faculty boards. -

New York, New York“

Bemerkungen zu „New York, New York“ Erscheinungsjahr: 1977 Regisseur: Martin Scorsese Mitwirkende: Robert de Niro, Liza Minelli, Lionel Stander, Barry Primus, Mary Kay Place, Georgie Auld Französisches Filmplakat Inhaltsübersicht: August 1945. In Amerika (speziell in New York) wird der V-J Day (Victory over Japan Day, Tag des Kriegsende mit Japan) begeistert gefeiert. Auf dem Times Square in New York tanzen und umarmen sich unbekannte Menschen. Jimmy Doyle (Robert de Niro), ein Saxophonist, tauscht sein Armee-Hemd gegen ein Hawaii-Hemd und taucht in die Menge ein. Später landet er in einem Nachtklub. Dort spielt Tommy Dorsey (dargestellt vom Bandleader/Posaunisten Bill Tole) mit seiner Band im Rahmen einer Rundfunkübertragung zum Tanz auf. Zu den Klängen von „I’m getting sentimental over you“, „Song of India“ und „Opus Number One“ feiert man. Jimmy versucht in diesem Club eine Partnerin zu finden. Plump und erfolglos flirtet er mit mehreren Frauen. Dort trifft er auch die junge Francine Evans (Liza Minelli). Sie hat im Krieg bei der Truppenbetreuung getingelt und hofft jetzt auf eine Karriere als Sängerin. Francine gibt sich abweisend und spröde, aber Jimmy lässt nicht locker und will die Telefonnummer von ihr. Jimmy Doyle (Robert de Niro) und Francine Evans (Liza Minelli) im Nachtklub Am nächsten Morgen teilen sich beide zufälligerweise ein Taxi. Jimmy muss zu einem Vorspiel, da er Arbeit als Musiker sucht. Er nimmt Francine zur Audition mit. Der Veranstalter, der das Vorspiel organisierte, mag das Bebop-Saxophonspiel von Jimmy nicht. Um den Musikagenten versöhnlich zu stimmen singt Francine den Jazzstandard "You brought a new kind of love to me", Jimmy begleitet sie mit dem Saxophon. -

Expansión Y Entretenimiento

EDITORIAL Expansión y entretenimiento na vez más queremos expresar nuestra satisfacción de poder llegar a nuestros lectores con una nueva edición de Costa Urbana, una revista –¡nuestra revista!– que U sintetiza la concreción de sueños y desafíos que nos impusimos cuando decidimos poner a la consideración general un producto periodístico atractivo, interesante, dinámico, con distribución a todos los sectores sociales de Puerto Madero y el ámbito costero de Buenos Aires, desde Tigre hasta Quilmes. Y en esta dinámica de expansión, queremos reafirmar también que Costa Urbana continúa llegando a todos los sectores de la cultura, el turismo y otras esferas sociales de la provincia del Chaco y el territorio de Tierra del Fuego. En la presente edición de Costa Urbana el lector hallará un material periodístico de excepción. A saber: una entrevista exclusiva desde Hollywood con una megaestrella internacional como lo es Robert De Niro; les contamos la verdadera historia de Eliot Ness, aquel policía emblemático y anticorruptible que cobró dimensión internacional a través del cine y la televisión; visitamos la mítica catedral de Notre Dame, en el corazón de París; recorrimos la ciudad de Buenos Aires para mostrarles las cúpulas que encierran las más increíbles historias y, entre otros temas, nos fuimos al sur de la Argentina, más precisamente a Puerto Pirámides, para registrar el avistaje de ballenas, ese fenómeno anual que generan los cetáceos australes al llegar a la Península Valdés para su reproducción. Por supuesto que todo este material se ofrece con el marco de nuestras acostumbradas notas sobre la moda internacional, salud, lecturas, biografías de celebridades mundiales (en este número, Edith Piaf), galería de personajes, noticias corporativas y un auto-test para los amantes de los automotores de última generación. -

Roger Ebert's

The College of Media at Illinois presents Roger19thAnnual Ebert’s Film Festival2017 April 19-23, 2017 The Virginia Theatre Chaz Ebert: Co-Founder and Producer 203 W. Park, Champaign, IL Nate Kohn: Festival Director 2017 Roger Ebert’s Film Festival The University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign The College of Media at Illinois Presents... Roger Ebert’s Film Festival 2017 April 19–23, 2017 Chaz Ebert, Co-Founder, Producer, and Host Nate Kohn, Festival Director Casey Ludwig, Assistant Director More information about the festival can be found at www.ebertfest.com Mission Founded by the late Roger Ebert, University of Illinois Journalism graduate and a Pulitzer Prize- winning film critic, Roger Ebert’s Film Festival takes place in Urbana-Champaign each April for a week, hosted by Chaz Ebert. The festival presents 12 films representing a cross-section of important cinematic works overlooked by audiences, critics and distributors. The films are screened in the 1,500-seat Virginia Theatre, a restored movie palace built in the 1920s. A portion of the festival’s income goes toward on-going renovations at the theatre. The festival brings together the films’ producers, writers, actors and directors to help showcase their work. A film- maker or scholar introduces each film, and each screening is followed by a substantive on-stage Q&A discussion among filmmakers, critics and the audience. In addition to the screenings, the festival hosts a number of academic panel discussions featuring filmmaker guests, scholars and students. The mission of Roger Ebert’s Film Festival is to praise films, genres and formats that have been overlooked. -

(500) Days of Summer 2009

(500) Days of Summer 2009 (Sökarna) 1993 [Rec] 2007 ¡Que Viva Mexico! - Leve Mexiko 1979 <---> 1969 …And Justice for All - …och rättvisa åt alla 1979 …tick…tick…tick… - Sheriff i het stad 1970 10 - Blåst på konfekten 1979 10, 000 BC 2008 10 Rillington Place - Stryparen på Rillington Place 1971 101 Dalmatians - 101 dalmatiner 1996 12 Angry Men - 12 edsvurna män 1957 127 Hours 2010 13 Rue Madeleine 1947 1492: Conquest of Paradise - 1492 - Den stora upptäckten 1992 1900 - Novecento 1976 1941 - 1941 - ursäkta, var är Hollywood? 1979 2 Days in Paris - 2 dagar i Paris 2007 20 Million Miles to Earth - 20 miljoner mil till jorden 1957 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea - En världsomsegling under havet 1954 2001: A Space Odyssey - År 2001 - ett rymdäventyr 1968 2010 - Year We Make Contact, The - 2010 - året då vi får kontakt 1984 2012 2009 2046 2004 21 grams - 21 gram 2003 25th Hour 2002 28 Days Later - 28 dagar senare 2002 28 Weeks Later - 28 veckor senare 2007 3 Bad Men - 3 dåliga män 1926 3 Godfathers - Flykt genom öknen 1948 3 Idiots 2009 3 Men and a Baby - Tre män och en baby 1987 3:10 to Yuma 2007 3:10 to Yuma - 3:10 till Yuma 1957 300 2006 36th Chamber of Shaolin - Shaolin Master Killer - Shao Lin san shi liu fang 1978 39 Steps, The - De 39 stegen 1935 4 månader, 3 veckor och 2 dagar - 4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days 2007 4: Rise of the Silver Surfer - Fantastiska fyran och silversurfaren 2007 42nd Street - 42:a gatan 1933 48 Hrs. -

Finding Aid to the Historymakers ® Video Oral History with Chaz Ebert

Finding Aid to The HistoryMakers ® Video Oral History with Chaz Ebert Overview of the Collection Repository: The HistoryMakers®1900 S. Michigan Avenue Chicago, Illinois 60616 [email protected] www.thehistorymakers.com Creator: Ebert, Chaz, 1952- Title: The HistoryMakers® Video Oral History Interview with Chaz Ebert, Dates: August 7, 2017 Bulk Dates: 2017 Physical 5 uncompressed MOV digital video files (2:30:48). Description: Abstract: Lawyer Chaz Ebert (1952 - ) worked as a litigation attorney and served as vice president of the Ebert Company Ltd. Ebert was interviewed by The HistoryMakers® on August 7, 2017, in Chicago, Illinois. This collection is comprised of the original video footage of the interview. Identification: A2017_121 Language: The interview and records are in English. Biographical Note by The HistoryMakers® Lawyer and entertainment manager Chaz Ebert was born on October 15, 1952 in Chicago, Illinois to Johnnie Hobbs Hammel and Wiley Hammel, Sr. She attended John M. Smyth Elementary School and Crane Technical High School in Chicago, Illinois and graduated in 1969. Ebert earned her B.A. degree in political science at the University of Dubuque in Dubuque, Iowa in 1972. She then received her M.A. degree in social science at the University of Wisconsin-Platteville in Platteville, Wisconsin. Ebert went on to receive her J.D. degree from DePaul University College of Law in Chicago. Ebert began her career in 1977 as a litigator for the Region Five office of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. After three years, she left the agency to join the litigation department at the Chicago law firm of Bell Boyd and Lloyd LLP, where she focused on mergers and acquisitions and intellectual property. -

Historia Y Cine EEUU DIG.Indd

Coro Rubio Pobes (editora) La Historia a través del cine Estados Unidos: una mirada a su imaginario colectivo La Historia a través del cine Estados Unidos: una mirada a su imaginario colectivo Coro Rubio Pobes (editora) ARGITALPEN ZERBITZUA SERVICIO EDITORIAL La publicación de este libro ha sido posible gracias a la colaboración del Centro Cultural Montehermoso (Ayto. de Vitoria-Gasteiz) y el Instituto Valentín de Fo- ronda (UPV/EHU). © Servicio Editorial de la Universidad del País Vasco Euskal Herriko Unibertsitateko Argitalpen Zerbitzua ISBN: 978-84-9860-471-9 Depósito legal/Lege gordailua: BI - 3.394-2010 Fotocomposición/Fotokonposizioa: Ipar, S. Coop. Zurbaran, 2-4 - 48007 Bilbao Impresión/Inprimatzea : Itxaropena, S.A. Araba Kalea, 45 - 20800 Zarautz (Gipuzkoa) ÍNDICE Presentación. El imaginario estadounidense a través del cine Coro Rubio Pobes . 11 Glory (1989). Una visión dramatizada sobre el origen de los Buffalo Soldiers Óscar Álvarez Gila . 19 1. Introducción . 19 2. Glory (1989) . 22 3. El contexto histórico . 27 4. Entre la ficción y la historia: el 54.º Regimiento de Massachusetts . 37 5. Epílogo. 48 Ficha técnica . 49 Los violentos años veinte: gánsters, prohibición y cambios socio-políticos en el primer tercio del siglo XX en Estados Unidos Aurora Bosch . 51 1. Introducción . 51 2. Reformismo, americanismo y lucha contra el alcohol: respuestas históricas a cambios sociales rápidos . 53 3. La I Guerra Mundial y el triunfo de la prohibición . 64 4. Corrupción, violencia y criminalidad: la transforma- ción del mundo del crimen. 68 7 5. Movilización de clases medias contra la prohibición 75 6. Conclusión . 79 Ficha técnica . 81 La crisis de la democracia en América. -

Desk Set VOT V13 #1

Carl Denham presents THE BIRTH OF KONG by Ray Morton ing Kong was written by explorer and the brainchild naturalist W. Douglas Kof filmmaker Burden called THE Merian C. Cooper, DRAGON LIZARDS OF one of the pioneers of KOMODO. In 1926, the “Natural Drama” Burden led an expedition – movies created by to the Dutch East Indian traveling to exotic island of Komodo, lands, shooting home of the famed documentary footage Komodo Dragons, a of the native people species of large, vicious and events, and then, lizards thought to have through creative editing been extinct since (and by occasionally prehistoric times until staging events for the the living specimens camera), shaping that were discovered in 1912. footage into a dramatic narrative that had all of the Borrowing the idea of an expedition to a remote island thrills and excitement of a fictional adventure film. for his story, Cooper also decided that the Dragons A former merchant seaman, newspaper reporter and would make ideal antagonists for his ape and began military aviator, Cooper and his partner, former combat dreaming up scenes in which the creatures would fight cinematographer Ernest B. Schoedsack, traveled to Persia --scenes he planned to realize by filming the animals and Thailand to produce two classic Natural Dramas separately in their natural habitats and then intercutting – Grass: A Nation’s Battle for Life (1925) and Chang the footage. Learning that Burden had captured two (1927) -- and used their talents to create unique location Dragons, brought them to New York, and exhibited them footage for Paramount’s 1929 African-set adventure The at the Bronx Zoo until they died, Cooper decided to do Four Feathers. -

1 Evolving Authorship, Developing Contexts: 'Life Lessons'

Notes 1 Evolving Authorship, Developing Contexts: ‘Life Lessons’ 1. This trajectory finds its seminal outlining in Caughie (1981a), being variously replicated in, for example, Lapsley and Westlake (1988: 105–28), Stoddart (1995), Crofts (1998), Gerstner (2003), Staiger (2003) and Wexman (2003). 2. Compare the oft-quoted words of Sarris: ‘The art of the cinema … is not so much what as how …. Auteur criticism is a reaction against sociological criticism that enthroned the what against the how …. The whole point of a meaningful style is that it unifies the what and the how into a personal state- ment’ (1968: 36). 3. For a fuller discussion of the conception of film authorship here described, see Grist (2000: 1–9). 4. While for this book New Hollywood Cinema properly refers only to this phase of filmmaking, the term has been used by some to designate ‘either something diametrically opposed to’ such filmmaking, ‘or some- thing inclusive of but much larger than it’ (Smith, M. 1998: 11). For the most influential alternative position regarding what he calls ‘the New Hollywood’, see Schatz (1993). For further discussion of the debates sur- rounding New Hollywood Cinema, see Kramer (1998), King (2002), Neale (2006) and King (2007). 5. ‘Star image’ is a concept coined by Richard Dyer in relation to film stars, but it can be extended to other filmmaking personnel. To wit: ‘A star image is made out of media texts that can be grouped together as promotion, publicity, films and commentaries/criticism’ (1979: 68). 6. See, for example, Grant (2000), or the conception of ‘post-auteurism’ out- lined and critically demonstrated in Verhoeven (2009).