1. Movies and Memorials

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

See It Big! Action Features More Than 30 Action Movie Favorites on the Big

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE ‘SEE IT BIG! ACTION’ FEATURES MORE THAN 30 ACTION MOVIE FAVORITES ON THE BIG SCREEN April 19–July 7, 2019 Astoria, New York, April 16, 2019—Museum of the Moving Image presents See It Big! Action, a major screening series featuring more than 30 action films, from April 19 through July 7, 2019. Programmed by Curator of Film Eric Hynes and Reverse Shot editors Jeff Reichert and Michael Koresky, the series opens with cinematic swashbucklers and continues with movies from around the world featuring white- knuckle chase sequences and thrilling stuntwork. It highlights work from some of the form's greatest practitioners, including John Woo, Michael Mann, Steven Spielberg, Akira Kurosawa, Kathryn Bigelow, Jackie Chan, and much more. As the curators note, “In a sense, all movies are ’action’ movies; cinema is movement and light, after all. Since nearly the very beginning, spectacle and stunt work have been essential parts of the form. There is nothing quite like watching physical feats, pulse-pounding drama, and epic confrontations on a large screen alongside other astonished moviegoers. See It Big! Action offers up some of our favorites of the genre.” In all, 32 films will be shown, many of them in 35mm prints. Among the highlights are two classic Technicolor swashbucklers, Michael Curtiz’s The Adventures of Robin Hood and Jacques Tourneur’s Anne of the Indies (April 20); Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai (April 21); back-to-back screenings of Mad Max: Fury Road and Aliens on Mother’s Day (May 12); all six Mission: Impossible films -

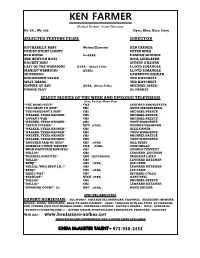

K E N F a R M

KEN FAR MER (Partial Resume- Actor/Director) Ht: 6ft., Wt: 200 Eyes: Blue, Hair: Grey SELECTED FEATURE FILMS DIRECTOR ROCKABILLY BABY Writer/Director KEN FARMER FRIDAY NIGHT LIGHTS PETER BERG RED RIDGE Co-STAR DAMIAN SKINNER THE NEWTON BOYS RICK LINKLATER ROCKET MAN STUART GILLARD LAST OF THE WARRIORS (STAR, - Above Title) LLOYD SIMANDLE MANIAC WARRIORS (STAR) LLOYD SIMANDLE SILVERADO LAWRENCE KASDAN UNCOMMON VALOR TED KOTCHEFF SPLIT IMAGE TED KOTCHEFF EMPIRE OF ASH (STAR - Above Title) MICHAEL MAZO POWER PLAY AL FRAKES SELECT MOVIES OF THE WEEK AND EPISODIC TELEVISION (Star, Co-Star, Guest Star) “THE GOOD GUYS” FOX SANFORD BOOKSTAVER "TOO LEGIT TO QUIT" VH1 ARTIE MANDELBERG "THE PRESIDENT'S MAN" CBS MICHAEL PREECE "WALKER, TEXAS RANGER" CBS MICHAEL PREECE "LOGAN'S WAR" CBS MICHAEL PREECE "WALKER, TEXAS RANGER" CBS TONY MORDENTE "AUSTIN STORIES" MTV (STAR) GEORGE VERSHOOR "WALKER, TEXAS RANGER" CBS ALEX SINGER "WALKER, TEXAS RANGER" CBS TONY MORDENTE "WALKER, TEXAS RANGER" CBS MICHAEL PREECE "WALKER, TEXAS RANGER" CBS TONY MORDENTE "ANOTHER PAIR OF ACES" CBS (STAR) BILL BIXBY "AMERICA'S MOST WANTED" FOX (STAR) TOM SHELLY "HIGH MOUNTAIN RANGERS" CBS GEORGE FENNEDY "DALLAS" CBS LEONARD KATZMAN "GENERAL HOSPITAL" ABC (RECURRING) MARLENA LAIRD "DALLAS" CBS LEONARD KATZMAN "BENJI" CBS (STAR) JOE CAMP "DALLAS, WHO SHOT J.R.?" CBS LEONARD KATZMAN "BENJI" CBS (STAR) JOE CAMP "JAKE'S WAY" CBS RICHARD COLLA "BACKLOT" NICK (STAR) GARY PAUL "DALLAS" CBS MICHAEL PREECE "DALLAS" CBS LEONARD KATZMAN "SUPERIOR COURT" (2) NBC (STAR) HANK GRIMER SPECIAL ABILITIES EXPERT HORSEMAN: ALL SPORTS: COLLEGE ALL-AMERICAN, FOOTBALL: EXCELLENT SWIMMER: DIVING: SCUBA: WRESTLING: HAND-TO-HAND COMBAT: USMC: FAMILIAR WITH ALL TYPES OF FIREARMS: CAN FURNISH OWN FILM TRAINED HORSE: BACHELOR'S DEGREE - SPEECH & DRAMA : GOLF: AUTHOR OF "ACTING IS STORYTELLING ©" : ACTING COACH: STORYTELLING CONSULTANT: PRODUCER: DIRECTOR Web Site - www.kenfarmer-author.net THEATRICAL AND COMMERCIAL DVD & AUDIO TAPES AVAILABLE LINDA McALISTER TALENT - 972-938-2433. -

The Whistleblowers

A U S F I L M Australian Familiarisation Event Mathew Tang Producer Mathew Tang began his career in 1989 and has since worked on over 30 feature films, covering various creative and production duties that include assistant directing, line-producing, writing, directing and producing. In 1999, Mathew debuted as a screenwriter on The Kid, a film that went on to win Best Supporting Actor and Actress in the Hong Kong Film Awards. In 2005, he wrote, edited and directed his debut feature B420 which received The Grand Prix Award at the 19th Fukuoka Asian Film Festival and Best Film at the 4th Viennese Youth International Film Festival in 2007. Mathew served as Associate Producer and Line Producer on Forbidden Kingdom and oversaw the Hollywood blockbuster’s entire production in China. In 2008 and 2009 he was Vice President of Celestial Pictures. From 2009- 2012, he was the Head of Productions at EDKO Films Ltd. In the summer of 2012, he founded Movie Addict Productions and the company produced four movies. Mathew is currently an Invited Executive Member of the Hong Kong Screenwriters’ Guild and a Panel Examiner of the Hong Kong Film Development Council. Johnny Wang Line Producer Johnny Wang started working for the movie industry in 1989 and by the year 2002, he started working at Paramount Studios on the project Tomb Raider 2 as production supervisor on location in Hong Kong. Since then, he has line produced 20 movies in Hong Kong, China and other locations around the world. Johnny has been an executive board member of the HKMPEA (Hong Kong Movie Production Executives Association) for more than four years. -

Cutting Patterns in DW Griffith's Biographs

Cutting patterns in D.W. Griffith’s Biographs: An experimental statistical study Mike Baxter, 16 Lady Bay Road, West Bridgford, Nottingham, NG2 5BJ, U.K. (e-mail: [email protected]) 1 Introduction A number of recent studies have examined statistical methods for investigating cutting patterns within films, for the purposes of comparing patterns across films and/or for summarising ‘average’ patterns in a body of films. The present paper investigates how different ideas that have been proposed might be combined to identify subsets of similarly constructed films (i.e. exhibiting comparable cutting structures) within a larger body. The ideas explored are illustrated using a sample of 62 D.W Griffith Biograph one-reelers from the years 1909–1913. Yuri Tsivian has suggested that ‘all films are different as far as their SL struc- tures; yet some are less different than others’. Barry Salt, with specific reference to the question of whether or not Griffith’s Biographs ‘have the same large scale variations in their shot lengths along the length of the film’ says the ‘answer to this is quite clearly, no’. This judgment is based on smooths of the data using seventh degree trendlines and the observation that these ‘are nearly all quite different one from another, and too varied to allow any grouping that could be matched against, say, genre’1. While the basis for Salt’s view is clear Tsivian’s apparently oppos- ing position that some films are ‘less different than others’ seems to me to be a reasonably incontestable sentiment. It depends on how much you are prepared to simplify structure by smoothing in order to effect comparisons. -

Combat Motivation in the Iraq War

WHY THEY FIGHT: COMBAT MOTIVATION IN THE IRAQ WAR Leonard Wong Thomas A. Kolditz Raymond A. Millen Terrence M. Potter July 2003 ***** The views expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Army, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government. This report is cleared for public release; distribution is unlimited. ***** This study was greatly supported by members of the 800th Military Police Brigade -- specifically BG Paul Hill, COL Al Ecke, and LTC James O’Hare. Staff Judge Advocates COL Ralph Sabbatino and COL Karl Goetzke also provided critical guidance. Finally, COL Jim Embrey planned and coordinated the visits to units for this study. ***** Comments pertaining to this report are invited and should be forwarded to: Director, Strategic Studies Institute, U.S. Army War College, 122 Forbes Ave, Carlisle, PA 17013-5244, or directly to [email protected] Copies of this report may be obtained from the Publications Office by calling (717) 245-4133, FAX (717) 245-3820, or by e-mail at [email protected] ***** All Strategic Studies Institute (SSI) monographs are available on the SSI Homepage for electronic dissemination. SSI’s Homepage address is: http:// www.carlisle.army.mil/ssi/ ***** The Strategic Studies Institute publishes a monthly e-mail newsletter to update the national security community on the research of our analysts, recent and forthcoming publications, and upcoming conferences sponsored by the Institute. Each newsletter also provides a strategic commentary by one of our research analysts. If you are interested in receiving this newsletter, please let us know by e-mail at [email protected] or by calling (717) 245-3133. -

The Construction of Muslim Terrorism in the Kingdom Movie (2007) Directed by Peter Berg: a Reception Theory Magister of Language

THE CONSTRUCTION OF MUSLIM TERRORISM IN THE KINGDOM MOVIE (2007) DIRECTED BY PETER BERG: A RECEPTION THEORY PUBLICATION ARTICLE Submitted as a Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Getting Master Degree of Education in Magister of Language Study by: Agung Budi Santoso S200130035 MAGISTER OF LANGUAGE STUDY MUHAMMADIYAH UNIVERSITY OF SURAKARTA 2015 i ii iii 1 THE CONSTRUCTION OF MUSLIM TERRORISM IN THE KINGDOM MOVIE (2007) DIRECTED BY PETER BERG: A RECEPTION THEORY Agung Budi Santoso Magister of Language Study Muhammadiyah University of Surakarta Abstract This study belongs to the literary study. This study analyzes the construction of Muslim terrorism based on reader response reflected in The Kingdom Movie (2007). There are two objectives of the study, the first is to describe the dominant issues by the reviewers in applying reader response theory to Peter Berg‟s The Kingdom movie, and the second is to explain the reason why the dominant issue are perceived differently by reviewers. This study is a qualitative study and using two data sources; they are primary and secondary data. The primary data source is the reviews of The Kingdom movie (2007) by Peter Berg from IMDb (Internet Movie Database). The secondary data of this study are taken from other sources such as literary book, previous studies, articles, journals, and also website related to reader response theory. This study aimed to reveal how the cultural reader response reflected to The Kingdom movie. The dominant issue which is respond by the reviewers is the terrorism dealing with the culture reader response. Keywords: Culture Reader Response, Richard Beach, The Kingdom Abstrak Penelitian ini termasuk dalam penelitian sastra. -

Public Politics/Personal Authenticity

PUBLIC POLITICS/PERSONAL AUTHENTICITY: A TALE OF TWO SIXTIES IN HOLLYWOOD CINEMA, 1986- 1994 Oliver Gruner Thesis submitted for the degree of Ph.D. University of East Anglia School of Film and Television Studies August, 2010 ©This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that no quotation from the thesis, nor any information derived therefrom, may be published without the author’s prior, written consent. 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 5 Chapter One “The Enemy was in US”: Platoon and Sixties Commemoration 62 Platoon in Production, 1976-1982 65 Public Politics/Personal Authenticity: Platoon from Script to Screen 73 From Vietnam to the Sixties: Promotion and Reception 88 Conclusion 101 Chapter Two “There are a lot of things about me that aren’t what you thought”: Dirty Dancing and Women’s Liberation 103 Dirty Dancing in Production, 1980-1987 106 Public Politics/Personal Authenticity: Dirty Dancing from Script to Screen 114 “Have the Time of Your Life”: Promotion and Reception 131 Conclusion 144 Chapter Three Bad Sixties/ Good Sixties: JFK and the Sixties Generation 146 Lost Innocence/Lost Ignorance: Kennedy Commemoration and the Sixties 149 Innocence Lost: Adaptation and Script Development, 1988-1991 155 In Search of Authenticity: JFK ’s “Good Sixties” 164 Through the Looking Glass: Promotion and Reception 173 Conclusion 185 Chapter Four “Out of the Prison of Your Mind”: Framing Malcolm X 188 A Civil Rights Sixties 191 A Change -

Coping Strategies: Three Decades of Vietnam War in Hollywood

Coping Strategies: Three Decades of Vietnam War in Hollywood EUSEBIO V. LLÁCER ESTHER ENJUTO The Vietnam War represents a crucial moment in U.S. contemporary history and has given rise to the conflict which has so intensively motivated the American film industry. Although some Vietnam movies were produced during the conflict, this article will concentrate on the ones filmed once the war was over. It has been since the end of the war that the subject has become one of Hollywood's best-sellers. Apocalypse Now, The Return, The Deer Hunter, Rambo or Platoon are some of the titles that have created so much controversy as well as related essays. This renaissance has risen along with both the electoral success of the conservative party, in the late seventies, and a change of attitude in American society toward the recently ended conflict. Is this a mere coincidence? How did society react to the war? Do Hollywood movies affect public opinion or vice versa? These are some of the questions that have inspired this article, which will concentrate on the analysis of popular films, devoting a very brief space to marginal cinema. However, a general overview of the conflict it self and its repercussions, not only in the soldiers but in the civilians back in the United States, must be given in order to comprehend the between and the beyond the lines of the films about Vietnam. Indochina was a French colony in the Far East until its independence in 1954, when the dictator Ngo Dinh Diem took over the government of the country with the support of the United States. -

Female Director Takes Hollywood by Storm: Is She a Beauty Or a Visionary?

Western Oregon University Digital Commons@WOU Honors Senior Theses/Projects Student Scholarship 6-1-2016 Female Director Takes Hollywood by Storm: Is She a Beauty or a Visionary? Courtney Richardson Western Oregon University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/honors_theses Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons Recommended Citation Richardson, Courtney, "Female Director Takes Hollywood by Storm: Is She a Beauty or a Visionary?" (2016). Honors Senior Theses/Projects. 107. https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/honors_theses/107 This Undergraduate Honors Thesis/Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at Digital Commons@WOU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Senior Theses/Projects by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@WOU. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. Female Director Takes Hollywood by Storm: Is She a Beauty or a Visionary? By Courtney Richardson An Honors Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation from the Western Oregon University Honors Program Dr. Shaun Huston, Thesis Advisor Dr. Gavin Keulks, Honors Program Director Western Oregon University June 2016 2 Acknowledgements First I would like to say a big thank you to my advisor Dr. Shaun Huston. He agreed to step in when my original advisor backed out suddenly and without telling me and really saved the day. Honestly, that was the most stressful part of the entire process and knowing that he was available if I needed his help was a great relief. Second, a thank you to my Honors advisor Dr. -

Luther Lee Sanders '64 1 Luther Lee Sanders '64

Honoring….. Honoring…LUTHER LEE SANDERS '64 1 LUTHER LEE SANDERS '64 Captain, United States Army Presidential Unit Citation Vietnamese Cross of Gallantry 1st Cav Div 101st Abn Div 1965 ‐ 1966 1969 th 3 Bn 187 Para Inf “Rakkasans” While at Texas A&M... Before Texas A&M... When anyone uses the term “Son of the Service”, In September 1960, Lee Sanders travelled from think of Luther Lee Sanders. Lee was born in Colo- Vacaville, California to College Station where he en- rado Springs, spent his childhood in several places rolled as an Agricultural Economics major. Back then, around the world, and attended three different high Army cadets who were students in the College of Agri- schools before graduating from Vacaville High culture were assigned to Company D-1 or “Spider D”. School, just outside Travis AFB, California. A few weeks into our Fish Year, Lee was one of several At an early age, Lee learned the value and hundred who tried-out for the Fish Drill Team. Lee cer- importance of non-commissioned officers tainly knew how to do Drill and Ceremonies. When the in any organization – especially when it selection process eliminated most of the hundreds who comes to maintaining “good order and tried, Lee was one of the 44 freshmen selected. From discipline”. Lee’s father was a Chief Mas- that point forward until Mother’s Day, Fish Drill Team ter Sergeant in the U. S. Air Force. was a big part of Lee’s effort. In fact, it was Master Sergeant Sanders who aimed Lee toward Texas A&M at an early age. -

2011 01 Newsletter Printer Final

January 2011 The Currahee! The Newsletter of the 506th Airborne Infantry Regiment Association (Airmobile — Air Assault) We Stand Together – then, now, and always Hill 996, A Shau Valley, July 10, 1969 1st Lt. Leonard “Len“ Griffin 2/319th Artillery, 101st Airborne Division Forward Observer to D Company, 1/506th, Vietnam 1969 On July 11, 1969, on a nondescript mountain top vived Hill 996 told our medic Rick “Doc” Daniels, ʺNo numbered 996 near Hamburger Hill in the A Shau Valley one will ever know what happened here.ʺ Seventeen of Vietnam, the 1/506th Infantry and other units engaged a days later Sgt Denton died in a mortar attack. I swore, if I larger NVA force. The day before, the forward observer could, I would take up Sgt. Denton’s challenge and tell for D 1/506th was injured jumping out of a helicopter on the story. When I decided to face my demons of Viet‐ the air assault. I was called and told to replace him and nam, I had to face Hill 996. Thanks to enormous support that is how I got involved with the men of the 506th and of those who were there with me, I made it. th Hill 996. By the end of the day on the 11 , 20 Americans I felt the men who didn’t walk off the Hill should had been killed and 26 wounded. Eight Silver Stars were be remembered and honored to some degree. Living awarded to the men and one Medal of Honor to SPC. near Toccoa, Georgia, the Mecca of the 101st Airborne Gordon Roberts who survived the war. -

"So God-Damned Far Away": Soldiers' Experiences in the Vietnam War

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Honors Theses Lee Honors College 5-9-2012 "So God-damned Far Away": Soldiers' Experiences in the Vietnam War Tara M. Bell [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/honors_theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Bell, Tara M., ""So God-damned Far Away": Soldiers' Experiences in the Vietnam War" (2012). Honors Theses. 1542. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/honors_theses/1542 This Honors Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Lee Honors College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WESTERN MICHIGAN UNIVERSITY The Carl and Winifred Lee Honors College THE CARL AND WINIFRED LEE HONORS COLLEGE CERTIFICATE OF ORAL DEFENSE OF HONORS THESIS Tara Bell, having been admitted to the Carl and Winifred Lee Honors College in the fall of 2008, successfully completed the Lee Honors College Thesis on May 09, 2012. The title of the thesis is: "So God-damned Far Away": Soldiers'Experiences in the Vietnam War Dr. Edwin Martini, History Scott Friesner, Lee Honors College Dr. Nicholas Andreadis, Lee Honors College 1903 W. Michigan Ave., Kalamazoo, Ml 49008-5244 PHONE: (269) 387-3230 FAX: (269) 387-3903 www.wmich.edu/honors The story of the Vietnam War cannot be told solely from the perspective of the political and military leaders of the war. For a complete understanding of the war one must look at the experiences of the common person, the soldiers who fought in the war.