By a Capstone Project Submitted for Graduation with University Honors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Blood-Soaked Olive: What Is the Situation in Afrin Today? by Anthony Avice Du Buisson - 06/10/2018 01:23

www.theregion.org A blood-soaked olive: what is the situation in Afrin today? by Anthony Avice Du Buisson - 06/10/2018 01:23 Afrin Canton in Syria’s northwest was once a haven for thousands of people fleeing the country’s civil war. Consisting of beautiful fields of olive trees scattered across the region from Rajo to Jindires, locals harvested the land and made a living on its rich soil. This changed when the region came under Turkish occupation this year. Operation Olive Branch: Under the governance of the Afrin Council – a part of the ‘Democratic Federation of Northern Syria’ (DFNS) – the region was relatively stable. The council’s members consisted of locally elected officials from a variety of backgrounds, such as Kurdish official Aldar Xelil who formerly co-headed the Movement for a Democratic Society (TEVDEM) – a political coalition of parties governing Northern Syria. Children studied in their mother tongue— Kurdish, Arabic, or Syriac— in a country where the Ba’athists once banned Kurdish education. The local Self-Defence Forces (HXP) worked in conjunction with the People’s Protection Units (YPG) to keep the area secure from existential threats such as Turkish Security forces (TSK) and Free Syrian Army (FSA) attacks. This arrangement continued until early 2018, when Turkey unleashed a full-scale military operation called ‘ Operation Olive Branch’ to oust TEVDEM from Afrin. The Turkish government views TEVDEM and its leading party, the Democratic Union Party (PYD), as an extension of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) – listed as a terrorist organisation in Turkey. Under the pretext of defending its borders from terrorism, the Turkish government sent thousands of troops into Afrin with the assistance of forces from its allies in Idlib and its occupied Euphrates Shield territories. -

Kurdish Political and Civil Movements in Syria and the Question of Representation Dr Mohamad Hasan December 2020

Kurdish Political and Civil Movements in Syria and the Question of Representation Dr Mohamad Hasan December 2020 KurdishLegitimacy Political and and Citizenship Civil Movements in inthe Syria Arab World This publication is also available in Arabic under the title: ُ ف الحركات السياسية والمدنية الكردية ي� سوريا وإشكالية التمثيل This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author. For questions and communication please email: [email protected] Cover photo: A group of Syrian Kurds celebrate Newroz 2007 in Afrin, source: www.tirejafrin.com The views and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE). This document is issued on the understanding that if any extract is used, the author and the LSE Conflict Research Programme should be credited, with the name and date of the publication. All rights reserved © LSE 2020. About Legitimacy and Citizenship in the Arab World Legitimacy and Citizenship in the Arab World is a project within the Civil Society and Conflict Research Unit at the London School of Economics. The project looks into the gap in understanding legitimacy between external policy-makers, who are more likely to hold a procedural notion of legitimacy, and local citizens who have a more substantive conception, based on their lived experiences. Moreover, external policymakers often assume that conflicts in the Arab world are caused by deep- seated divisions usually expressed in terms of exclusive identities. -

Two Routes to an Impasse: Understanding Turkey's

Two Routes to an Impasse: Understanding Turkey’s Kurdish Policy Ayşegül Aydin Cem Emrence turkey project policy paper Number 10 • December 2016 policy paper Number 10, December 2016 About CUSE The Center on the United States and Europe (CUSE) at Brookings fosters high-level U.S.-Europe- an dialogue on the changes in Europe and the global challenges that affect transatlantic relations. As an integral part of the Foreign Policy Studies Program, the Center offers independent research and recommendations for U.S. and European officials and policymakers, and it convenes seminars and public forums on policy-relevant issues. CUSE’s research program focuses on the transforma- tion of the European Union (EU); strategies for engaging the countries and regions beyond the frontiers of the EU including the Balkans, Caucasus, Russia, Turkey, and Ukraine; and broader European security issues such as the future of NATO and forging common strategies on energy security. The Center also houses specific programs on France, Germany, Italy, and Turkey. About the Turkey Project Given Turkey’s geopolitical, historical and cultural significance, and the high stakes posed by the foreign policy and domestic issues it faces, Brookings launched the Turkey Project in 2004 to foster informed public consideration, high‐level private debate, and policy recommendations focusing on developments in Turkey. In this context, Brookings has collaborated with the Turkish Industry and Business Association (TUSIAD) to institute a U.S.-Turkey Forum at Brookings. The Forum organizes events in the form of conferences, sem- inars and workshops to discuss topics of relevance to U.S.-Turkish and transatlantic relations. -

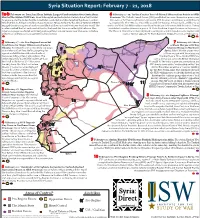

Syria SITREP Map 07

Syria Situation Report: February 7 - 21, 2018 1a-b February 10: Israel and Iran Initiate Largest Confrontation Over Syria Since 6 February 9 - 15: Turkey Creates Two Additional Observation Points in Idlib Start of the Syrian Civil War: Israel intercepted and destroyed an Iranian drone that violated Province: The Turkish Armed Forces (TSK) established two new observation points near its airspace over the Golan Heights. Israel later conducted airstrikes targeting the drone’s control the towns of Tal Tuqan and Surman in Eastern Idlib Province on February 9 and February vehicle at the T4 Airbase in Eastern Homs Province. Syrian Surface-to-Air Missile Systems (SAMS) 15, respectively. The TSK also reportedly scouted the Taftanaz Airbase north of Idlib City as engaged the returning aircraft and successfully shot down an Israeli F-16 over Northern Israel. The well as the Wadi Deif Military Base near Khan Sheikhoun in Southern Idlib Province. Turkey incident marked the first such combat loss for the Israeli Air Force since the 1982 Lebanon War. established a similar observation post at Al-Eis in Southern Aleppo Province on February 5. Israel in response conducted airstrikes targeting at least a dozen targets near Damascus including The Russian Armed Forces later deployed a contingent of military police to the regime-held at least four military positions operated by Iran in Syria. town of Hadher opposite Al-Eis in Southern Aleppo Province on February 14. 2 February 17 - 20: Pro-Regime Forces Set Qamishli 7 February 18: Ahrar Conditions for Major Offensive in Eastern a-Sham Merges with Key Ghouta: Pro-regime forces intensified a campaign 9 Islamist Group in Northern of airstrikes and artillery shelling targeting the 8 Syria: Salafi-Jihadist group Ahrar opposition-held Eastern Ghouta suburbs of Al-Hasakah a-Sham merged with Islamist group Damascus, killing at least 250 civilians. -

Mesopotamian Social Sciences Academy

Mesopotamian Social Sciences Academy The Mesopotamian Academy, affiliated to the Social Justice Council, was founded in Qamishlo in 2013 in order to create a new and free-thinking society. The Academy, with its experienced staff, carries out work in scientific studies. After its opening, the Academyâ™s education system has gone through many changes, as the aim is to continuously improve and strengthen the system. This period consists of two parts, Sociology and Science History, and lasts 4 months. Students who successfully complete all three sessions, after the proper evaluation, would then begin their studies in the chosen field in the Autonomous Administration institutions. The Academy has successfully completed six education sessions so far, attended by hundreds of students. The Mesopotamian Social Sciences Academy is an educational institution in Qamishli, the capital of the de facto autonomous region Western Kurdistan. The academy opened on September 2014. Its curriculum focuses primarily on the democratic confederalism of Kurdish nationalist Abdullah Öcalan. University of Afrin. University of Rojava. Official Facebook page of the Mesopotamian Social Sciences Academy. We found one dictionary with English definitions that includes the word mesopotamian social sciences academy: Click on the first link on a line below to go directly to a page where "mesopotamian social sciences academy" is defined. General (1 matching dictionary). Mesopotamian Social Sciences Academy: Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia [home, info]. â–¸ Words similar to mesopotamian social sciences academy. â–¸ Words that often appear near mesopotamian social sciences academy. â–¸ Rhymes of mesopotamian social sciences academy. â–¸ Invented words related to mesopotamian social sciences academy. -

Kurdistan Rising? Considerations for Kurds, Their Neighbors, and the Region

KURDISTAN RISING? CONSIDERATIONS FOR KURDS, THEIR NEIGHBORS, AND THE REGION Michael Rubin AMERICAN ENTERPRISE INSTITUTE Kurdistan Rising? Considerations for Kurds, Their Neighbors, and the Region Michael Rubin June 2016 American Enterprise Institute © 2016 by the American Enterprise Institute. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be used or reproduced in any man- ner whatsoever without permission in writing from the American Enterprise Institute except in the case of brief quotations embodied in news articles, critical articles, or reviews. The views expressed in the publications of the American Enterprise Institute are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the staff, advisory panels, officers, or trustees of AEI. American Enterprise Institute 1150 17th St. NW Washington, DC 20036 www.aei.org. Cover image: Grand Millennium Sualimani Hotel in Sulaymaniyah, Kurdistan, by Diyar Muhammed, Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons. Contents Executive Summary 1 1. Who Are the Kurds? 5 2. Is This Kurdistan’s Moment? 19 3. What Do the Kurds Want? 27 4. What Form of Government Will Kurdistan Embrace? 56 5. Would Kurdistan Have a Viable Economy? 64 6. Would Kurdistan Be a State of Law? 91 7. What Services Would Kurdistan Provide Its Citizens? 101 8. Could Kurdistan Defend Itself Militarily and Diplomatically? 107 9. Does the United States Have a Coherent Kurdistan Policy? 119 Notes 125 Acknowledgments 137 About the Author 139 iii Executive Summary wo decades ago, most US officials would have been hard-pressed Tto place Kurdistan on a map, let alone consider Kurds as allies. Today, Kurds have largely won over Washington. -

1 of 4 Weekly Conflict Summary February 1-7, 2018 During The

Weekly Conflict Summary February 1-7, 2018 During the reporting period, the Turkish-led Operation Olive Branch offensive continued its advance into Afrin, the northwestern canton controlled by the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF, a US-backed, Kurdish- led organization). Elsewhere, pro-government forces continued their advance against opposition forces and ISIS fighters in the northern Hama/southern Aleppo countryside, further securing their control in the area. Following a significant uptick in attacks on both the opposition-controlled Idleb and Eastern Ghouta pockets, the UN humanitarian coordinator, Panos Moumtzis, called for an immediate one-month cessation of hostilities for the delivery of humanitarian aid. Lastly, a new opposition “operation room” has been formed in Idleb, with the stated goal of coordinating attacks against government forces. Figure 1 - Areas of control in Syria by February 7, with arrows indicating fronts of advance during the reporting period 1 of 4 Weekly Conflict Summary – February 1-7, 2018 Operation Olive Branch Operation Olive Branch forces took new territory, connecting previously isolated territories west of Raju and north of Balbal. Turkey-backed Operation Euphrates Shield forces also advanced northwest of A’zaz to take a mountaintop and village from the SDF. No gains have yet been made towards Tal Refaat along the southeastern front. There have been reports of abuses by advancing Turkish-backed, opposition Free Syrian Army (FSA) forces, including footage of Operation Olive Branch forces apparently mutilating the body of a deceased YPJ fighter (an all-female Kurdish unit within the SDF). Hundreds of US-trained YPG/SDF fighters from eastern SDF cantons arrived in Afrin this week, traveling through government-held territory to reinforce the SDF fighters on fronts against Olive Branch units. -

Prospects for Political Inclusion in Rojava and Iraqi Kurdistan

ISSUE BRIEF 09.05.18 False Hopes? Prospects for Political Inclusion in Rojava and Iraqi Kurdistan Mustafa Gurbuz, Ph.D., Arab Center, Washington D.C. Among those deeply affected by the Arab i.e., unifying Kurdish cantons in northern Spring were the Kurds—the largest ethnic Syria under a new local governing body, is minority without a state in the Middle depicted as a dream for egalitarianism and East. The Syrian civil war put the Kurds at a liberal inclusive culture that counters the forefront in the war against the Islamic patriarchic structures in the Middle East.1 State (IS) and drastically changed the future U.S. policy toward the Kurds, however, prospects of Kurds in both Syria and Iraq. has become most puzzling since the 2017 This brief examines the challenges that defeat of IS in Syria. While the U.S.—to hinder development of a politically inclusive avoid alienating the Turks—did not object culture in Syrian Kurdistan—popularly to the Turkish troops’ invasion of the known as Rojava—and Iraqi Kurdistan. Kurdish canton of Afrin, the YPG began Political and economic instability in both forging closer ties to Damascus—which regions have shattered Kurdish dreams for led to complaints from some American political diversity and prosperity since the officials that the Kurdish group “has turned early days of the Arab Spring. into an insurgent organization.”2 In fact, from the beginning of the Syrian civil war, Syrian Kurds have been most careful to not THE RISING TIDE OF SYRIAN KURDS directly target the Assad regime, aside from some short-term clashes in certain places The civil war in Syria has thus far bolstered like Rojava, for two major reasons. -

Women Rights in Rojava- English

Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................... 2 1- Women’s Political Role in the Autonomous Administration Project in Rojava ...................................... 3 1.1 Women’s Role in the Autonomous Administration ....................................................................... 3 1.1.1 Committees for Women ......................................................................................................... 4 1.1.2 The Women’s Committee ....................................................................................................... 4 1.1.3 Women’s Associations - The “Kongreya Star” ........................................................................ 5 1.2 Women’s Representation in Political and Administrative Bodies: ................................................. 6 2. Empowering Women in the Military Field ........................................................................................... 11 2.1 The Representation of Women in the Army ................................................................................ 11 2.2 The People’s Protection Units (YPG) and Women’s Protection Units (YPJ) ................................. 12 2.2.1 The Women’s Protection Units- YPJ ..................................................................................... 12 2.2.2 The People’s Protection Units- YPG ..................................................................................... -

Governing Rojava Layers of Legitimacy in Syria Contents

Research Paper Rana Khalaf Middle East and North Africa Programme | December 2016 Governing Rojava Layers of Legitimacy in Syria Contents Summary 2 Acronyms and Overview of Key Listed Actors 3 Introduction 5 PYD Pragmatism and the Emergence of ‘Rojava’ 8 Smoke and Mirrors: The PYD’s Search for Legitimacy Through Governance 10 1. Provision of security 12 2. Effectiveness in the provision of services 16 3. Diplomacy and image management 21 Conclusion: The Importance of Local Trust and Representation 24 About the Author 26 Acknowledgments 27 1 | Chatham House Governing Rojava: Layers of Legitimacy in Syria Summary • Syria is without functioning government in many areas but not without governance. In the northeast, the Democratic Union Party (PYD) has announced its intent to establish the federal region of Rojava. The PYD took control of the region following the Syrian regime’s handover in some Kurdish-majority areas and as a consequence of its retreat from others. In doing so, the PYD has displayed pragmatism and strategic clarity, and has benefited from the experience and institutional development of its affiliate organization, the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK). The PYD now seeks to further consolidate its power and to legitimize itself through the provision of security, services and public diplomacy; yet its local legitimacy remains contested. • The provision of security is paramount to the PYD’s quest for legitimacy. Its People’s Defense Units (YPG/YPJ) have been an effective force against the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS), winning the support of the local population, particularly those closest to the front lines. -

Turkey | Syria: Flash Update No. 2 Developments in Northern Aleppo

Turkey | Syria: Flash Update No. 2 Developments in Northern Aleppo, Azaz (as of 1 June 2016) Summary An estimated 16,150 individuals in total have been displaced by fighting since 27 May in the northern Aleppo countryside, with most joining settlements adjacent to the Bab Al Salam border crossing point, Azaz town, Afrin and Yazibag. Kurdish authorities in Afrin Canton have allowed civilians unimpeded access into the canton from roads adjacent to Azaz and Mare’ since 29 May in response to ongoing displacement near hostilities between ISIL and NSAGs. Some 9,000 individuals have been afforded safe passage to leave Mare’ and Sheikh Issa towns after they were trapped by fighting on 27 May; however, an estimated 5,000 civilians remain inside despite close proximity to frontlines. Humanitarian organisations continue to limit staff movement in the Azaz area for safety reasons, and some remain in hibernation. Limited, cautious humanitarian service delivery has started by some in areas of high IDP concentration. The map below illustrates recent conflict lines and the direction of movement of IDPs: United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) Coordination Saves Lives | www.unocha.org Turkey | Syria: Azaz, Flash Update No.2 Access Overview Despite a recent decline in hostilities since May 27, intermittent clashes continue between NSAGs and ISIL militants on the outskirts of Kafr Kalbien, Kafr Shush, Baraghideh, and Mare’ towns. A number of counter offensives have been coordinated by NSAGs operating in the Azaz sub district, hindering further advancements by ISIL militants towards Azaz town. As of 30 May, following the recent decline in escalations between warring parties, access has increased for civilians wanting to leave Azaz and Mare’ into areas throughout Afrin canton. -

Nation, Bordering and Identity on the Border Between Turkey and Iraq

University of Southampton Research Repository Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis and, where applicable, any accompanying data are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis and the accompanying data cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content of the thesis and accompanying research data (where applicable) must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder/s. When referring to this thesis and any accompanying data, full bibliographic details must be given, e.g. Thesis: Author (Year of Submission) "Full thesis title", University of Southampton, name of the University Faculty or School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination. Data: Author (Year) Title. URI [dataset] UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON FACULTY OF SOCIAL, HUMAN AND MATHEMATICAL SCIENCES Geography and Environment NATION, BORDERING AND IDENTITY ON THE BORDER BETWEEN TURKEY AND IRAQ by Bilal GORENTAS Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy SEPTEMBER 2016 UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON ABSTRACT FACULTY OF SOCIAL, HUMAN AND MATHEMATICAL SCIENCES Geography and Environment Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy NATION, BORDERING AND IDENTITY ON THE BORDER BETWEEN TURKEY AND IRAQ BILAL GORENTAS This thesis explores the impact of the border between Turkey and Iraq on Kurdish identity. Since the demarcation of the border in 1926, both Turkey and Iraq have struggled to accommodate their Kurdish citizens into their common national communities.