Aigina and the Naval Strategy of the Late Fifth and Early Fourth Centuries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Greek World

THE GREEK WORLD THE GREEK WORLD Edited by Anton Powell London and New York First published 1995 by Routledge 11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2003. Disclaimer: For copyright reasons, some images in the original version of this book are not available for inclusion in the eBook. Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 29 West 35th Street, New York, NY 10001 First published in paperback 1997 Selection and editorial matter © 1995 Anton Powell, individual chapters © 1995 the contributors All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Greek World I. Powell, Anton 938 Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication Data The Greek world/edited by Anton Powell. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. Greece—Civilization—To 146 B.C. 2. Mediterranean Region— Civilization. 3. Greece—Social conditions—To 146 B.C. I. Powell, Anton. DF78.G74 1995 938–dc20 94–41576 ISBN 0-203-04216-6 Master e-book ISBN ISBN 0-203-16276-5 (Adobe eReader Format) ISBN 0-415-06031-1 (hbk) ISBN 0-415-17042-7 (pbk) CONTENTS List of Illustrations vii Notes on Contributors viii List of Abbreviations xii Introduction 1 Anton Powell PART I: THE GREEK MAJORITY 1 Linear -

Ideals and Pragmatism in Greek Military Thought 490-338 Bc

Roel Konijnendijk IDEALS AND PRAGMATISM IN GREEK MILITARY THOUGHT 490-338 BC PhD Thesis – Ancient History – UCL I, Roel Konijnendijk, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. Thesis Abstract This thesis examines the principles that defined the military thinking of the Classical Greek city-states. Its focus is on tactical thought: Greek conceptions of the means, methods, and purpose of engaging the enemy in battle. Through an analysis of historical accounts of battles and campaigns, accompanied by a parallel study of surviving military treatises from the period, it draws a new picture of the tactical options that were available, and of the ideals that lay behind them. It has long been argued that Greek tactics were deliberately primitive, restricted by conventions that prescribed the correct way to fight a battle and limited the extent to which victory could be exploited. Recent reinterpretations of the nature of Greek warfare cast doubt on this view, prompting a reassessment of tactical thought – a subject that revisionist scholars have not yet treated in detail. This study shows that practically all the assumptions of the traditional model are wrong. Tactical thought was constrained chiefly by the extreme vulnerability of the hoplite phalanx, its total lack of training, and the general’s limited capacity for command and control on the battlefield. Greek commanders, however, did not let any moral rules get in the way of possible solutions to these problems. Battle was meant to create an opportunity for the wholesale destruction of the enemy, and any available means were deployed towards that goal. -

Conflict in the Peloponnese

CONFLICT IN THE PELOPONNESE Social, Military and Intellectual Proceedings of the 2nd CSPS PG and Early Career Conference, University of Nottingham 22-24 March 2013 edited by Vasiliki BROUMA Kendell HEYDON CSPS Online Publications 4 2018 Published by the Centre for Spartan and Peloponnesian Studies (CSPS), School of Humanities, University of Nottingham, Nottingham, NG7 2RD, UK. © Centre for Spartan and Peloponnesian Studies and individual authors ISBN 978-0-9576620-2-5 This work is ‘Open Access’, published under a creative commons license which means that you are free to copy, distribute, display, and perform the work as long as you clearly attribute the work to the authors, that you do not use this work for any commercial gain in any form and that you in no way alter, transform or build on the work outside of its use in normal academic scholarship without express permission of the authors and the publisher of this volume. Furthermore, for any reuse or distribution, you must make clear to others the license terms of this work. https://www.nottingham.ac.uk/csps TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD .................................................................................................................................. i THE FAMILY AS THE INTERNAL ENEMY OF THE SPARTAN STATE ........................................ 1-23 Maciej Daszuta COMMEMORATING THE WAR DEAD IN ANCIENT SPARTA THE GYMNOPAIDIAI AND THE BATTLE OF HYSIAI .............................................................. 24-39 Elena Franchi PHILOTIMIA AND PHILONIKIA AT SPARTA ......................................................................... 40-69 Michele Lucchesi SLAVERY AS A POLITICAL PROBLEM DURING THE PELOPONESSIAN WARS ..................... 70-85 Bernat Montoya Rubio TYRTAEUS: THE SPARTAN POET FROM ATHENS SHIFTING IDENTITIES AS RHETORICAL STRATEGY IN LYCURGUS’ AGAINST LEOCRATES ................................................................................ 86-102 Eveline van Hilten-Rutten THE INFLUENCE OF THE KARNEIA ON WARFARE .......................................................... -

Proud to Be Euboeans: the Chalcidians of Thrace

Proud to be Euboeans: The Chalcidians of Thrace Selene E. PSOMA Περίληψη Οι Χαλκιδείς της Θράκης, όπως αναφέρονται στην αρχαία γραμματεία και τις επιγραφές, ήταν Ευ- βοείς άποικοι στη χερσόνησο της Χαλκιδικής που ζούσαν σε μικρές πόλεις στο μυχό του κόλπου της Τορώνης και στη Σιθωνία. Η Όλυνθος παραδόθηκε στους Χαλκιδείς το 479 και εκείνοι αργότερα δη- μιούργησαν το ισχυρό κοινό των Χαλκιδέων. Οι δεσμοί τους με τη μητρόπολη τεκμαίρονται από το ημερολόγιο τους, την ονοματολογία, το χαλκιδικό αλφάβητο, το ακροφωνικό σύστημα αρίθμησης, καθώς επίσης και από τη νομισματοκοπία. Αυτό το άρθρο εξετάζει όλα τα στοιχεία δίνοντας ιδιαίτερη έμφαση στη νομισματοκοπία. Introduction The ties between Euboean Chalcis and the Chalcidians of Thrace are mentioned by both Aristotle and authors of later date.1 Aristotle, who was born a Chalcidian of Thrace and died in Chalcis, mentions that the Chalcidians of Thrace asked Androdamas of Rhegion to become their lawgiver (nomothetes).2 Rhegion was also a Chalcidian colony, and it was quite common for a colony to ask for lawgivers from one of its sister cities. Another story that Aristotle relates will be discussed at length later. According to Polybius, the Chalcidians of Thrace were colonists of both Athens and Chalcis, and the main opponent to Philip II in Thrace.3 Strabo noted that Eretria founded the cities of Pallene and Athos whereas Chalcis founded those near Olynthus.4 The foundation of these colonies took place when the Hippobotai were rul- ing Chalcis, and the men who led the colonists were among the noblest of their cities. Plutarch mentions the struggle between Chalcidians and Andrians over the foundation of Akanthos in the 7th century BC.5 1. -

Interstate Alliances of the Fourth-Century BCE Greek World: a Socio-Cultural Perspective

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 9-2016 Interstate Alliances of the Fourth-Century BCE Greek World: A Socio-Cultural Perspective Nicholas D. Cross The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/1479 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] INTERSTATE ALLIANCES IN THE FOURTH-CENTURY BCE GREEK WORLD: A SOCIO-CULTURAL PERSPECTIVE by Nicholas D. Cross A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2016 © 2016 Nicholas D. Cross All Rights Reserved ii Interstate Alliances in the Fourth-Century BCE Greek World: A Socio-Cultural Perspective by Nicholas D. Cross This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in History in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ______________ __________________________________________ Date Jennifer Roberts Chair of Examining Committee ______________ __________________________________________ Date Helena Rosenblatt Executive Officer Supervisory Committee Joel Allen Liv Yarrow THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Interstate Alliances of the Fourth-Century BCE Greek World: A Socio-Cultural Perspective by Nicholas D. Cross Adviser: Professor Jennifer Roberts This dissertation offers a reassessment of interstate alliances (συµµαχία) in the fourth-century BCE Greek world from a socio-cultural perspective. -

SPARTA, AMYNTAS, and the OLYNTHIANS in 383 B. C. a Comparison of Xenophon and Diodorus*

SPARTA, AMYNTAS, AND THE OLYNTHIANS IN 383 B. C. A comparison of Xenophon and Diodorus* After the swearing of the King’s Peace in 387 B. C. the Lacedaemonians anointed themselves its prostãtai or “cham- pions”; the modern “enforcers” surely conveys better the sinister implications of this championship. No sooner was the final text of the treaty presented for the swearing, than it became clear what ex- plosive potential the innocuous phrase (as formulated in the King’s edict) tåw ... ÑEllhn¤daw pÒleiw ka‹ mikråw ka‹ megãlaw aÈ- tonÒmouw éfe›nai1, “all the Greek cities both small and great are to be left autonomous”, had: the Thebans, who had desired to swear the Peace on behalf of all the Boeotian cities, rightly saw that it spelt the end of the Boeotian League when they were not allowed to do this2. In the hands of the Lacedaemonian leadership, which in those days strove hard to restore Lacedaemonian authority in Greece, it became a potent weapon. The diplomatic documents of the age carefully kept on the right side of the indicated clause – the treaty between Chios and Athens not only evinces the (for this period customary) deliberately parsed clauses, but actually refers to the maintenance of the King’s Peace as an overriding concern3. *) I thank Fritz Gschnitzer for reading an earlier draft of this paper which he improved immensely and also the anonymous referee of this journal. They hold no responsibility for its remaining deficiencies. 1) Xen. Hell. 5.1.31. The document – formally an edict of the Persian King – specifies a few exceptions. -

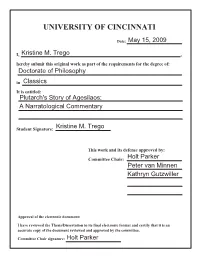

University of Cincinnati

U UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date: May 15, 2009 I, Kristine M. Trego , hereby submit this original work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Doctorate of Philosophy in Classics It is entitled: Plutarch's Story of Agesilaos; A Narratological Commentary Student Signature: Kristine M. Trego This work and its defense approved by: Committee Chair: Holt Parker Peter van Minnen Kathryn Gutzwiller Approval of the electronic document: I have reviewed the Thesis/Dissertation in its final electronic format and certify that it is an accurate copy of the document reviewed and approved by the committee. Committee Chair signature: Holt Parker Plutarch’s Story of Agesilaos; A Narratological Commentary A dissertation submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctorate of Philosophy (Ph.D.) in the Department of Classics of the College of Arts and Sciences 2009 by Kristine M. Trego B.A., University of South Florida, 2001 M.A. University of Cincinnati, 2004 Committee Chair: Holt N. Parker Committee Members: Peter van Minnen Kathryn J. Gutzwiller Abstract This analysis will look at the narration and structure of Plutarch’s Agesilaos. The project will offer insight into the methods by which the narrator constructs and presents the story of the life of a well-known historical figure and how his narrative techniques effects his reliability as a historical source. There is an abundance of exceptional recent studies on Plutarch’s interaction with and place within the historical tradition, his literary and philosophical influences, the role of morals in his Lives, and his use of source material, however there has been little scholarly focus—but much interest—in the examination of how Plutarch constructs his narratives to tell the stories they do. -

Herakleia Trachinia in the Archidamian War

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 1993 Herakleia Trachinia in the Archidamian War Mychal P. Angelos Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons Recommended Citation Angelos, Mychal P., "Herakleia Trachinia in the Archidamian War" (1993). Dissertations. 3292. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/3292 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1993 Mychal P. Angelos HERAKLEIA TRACHINIA IN THE ARCHIDAMIAN WAR By Mychal P. Angelos A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Loyola University of Chicago in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May, 1993 For Dorothy ·' ,/ ;~ '\ Copyright, 1993, Mychal P. Angelos, All rights reserved. VITA The author was born in Chicago, Illinois in 1929. He first entered Loyola University of Chicago in 1946 where he followed a liberal arts program. He was admitted to the University of Chicago Law School in 1948 and was awarded the Juris Doctor degree in 1951. He was admitted to the Illinois Bar in the same year and has been in private practice as an attorney in Chicago for 41 years. In September, 1982 he enrolled in the Department of History at Loyola University of Chicago, and in January, 1985 he received the Master of Arts degree in Ancient History. -

Companion Cavalry and the Macedonian Heavy Infantry

THE ARMY OP ALEXANDER THE GREAT %/ ROBERT LOCK IT'-'-i""*'?.} Submitted to satisfy the requirements for the degree of Ph.D. in the School of History in the University of Leeds. Supervisor: Professor E. Badian Date of Submission: Thursday 14 March 1974 IMAGING SERVICES NORTH X 5 Boston Spa, Wetherby </l *xj 1 West Yorkshire, LS23 7BQ. * $ www.bl.uk BEST COPY AVAILABLE. TEXT IN ORIGINAL IS CLOSE TO THE EDGE OF THE PAGE ABSTRACT The army with which Alexander the Great conquered the Persian empire was "built around the Macedonian Companion cavalry and the Macedonian heavy infantry. The Macedonian nobility were traditionally fine horsemen, hut the infantry was poorly armed and badly organised until the reign of Alexander II in 369/8 B.C. This king formed a small royal standing army; it consisted of a cavalry force of Macedonian nobles, which he named the 'hetairoi' (or Companion]! cavalry, and an infantry body drawn from the commoners and trained to fight in phalangite formation: these he called the »pezetairoi» (or foot-companions). Philip II (359-336 B.C.) expanded the kingdom and greatly increased the manpower resources for war. Towards the end of his reign he started preparations for the invasion of the Persian empire and levied many more Macedonians than had hitherto been involved in the king's wars. In order to attach these men more closely to himself he extended the meaning of the terms »hetairol» and 'pezetairoi to refer to the whole bodies of Macedonian cavalry and heavy infantry which served under him on his campaigning. -

ABSTRACT Constantinos Hasapis, Overcoming the Spartan

ABSTRACT Constantinos Hasapis, Overcoming the Spartan Phalanx: The Evolution of Greek Battlefield Tactics, 394 BC- 371 BC. (Dr. Anthony Papalas, Thesis Director), Spring 2012 The objective of this thesis is to examine the changes in Greek battlefield tactics in the early fourth century as a response to overthrowing what was widely considered by most of Greece tyranny on the part of Sparta. Sparta's hegemony was based on military might, namely her mastery of phalanx warfare. Therefore the key to dismantling Lacedaemonia's overlordship was to defeat her armies on the battlefield. This thesis will argue that new battle tactics were tried and although there were varying degrees of success, the final victory at Leuctra over the Spartans was due mainly to the use of another phalanx. However, the Theban phalanx was not a merely a copy of Sparta's. New formations, tactics, and battlefield concepts were applied and used successfully when wedded together. Sparta's prospects of maintaining her position of dominance were increasingly bleak. Sparta's phalanx had became more versatile and mobile after the end of the Peloponnesian War but her increasing economic and demographic problems, compounded by outside commitments resulting in imperial overstretch, strained her resources. The additional burden of internal security requirements caused by the need to hold down a massive helot population led to a static position in the face of a dynamic enemy with no such constraints Overcoming The Spartan Phalanx: The Evolution of Greek Battlefield Tactics, 394 BC-371 BC A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History East Carolina University In Partial Fulfillment for the Degree Master of Arts in History Constantinos Hasapis Spring 2012 Copyright 2012 Constantinos Hasapis Overcoming the Spartan Phalanx: The Evolution of Greek Battlefield Tactics, 394 BC-371 BC by Constantinos Hasapis APPROVED BY DIRECTOR OF THESIS ________________________________ Dr. -

Maintaining Peace and Interstate Stability in Archaic and Classical Greece

Alten Geschichte Studien zur Alten Geschichte Studien zur Alten Geschichte Studien zur Alten Geschichte Studien zur Alten Geschichte Studien zur Alten Geschichte Studien zur Alten Geschichte Studien zur Alten Ge Geschichte Studien zur Alten Geschichte Studien zur Alten Geschichte Studien zur Alten Geschichte Studien zur Alten Geschichte Studien zur Alten Geschichte Studien zur Alten Geschichte Studien Studien zur Alten Geschichte Studien zur Alten Geschichte Studien zur Alten Geschichte Studien zur Alten Geschichte Studien zur Alten Edited by Julia Wilker Geschichte Studien zur Alten Geschichte Studien zur Alten Geschichte Studien zur Alten Geschichte Studien zur Alten Geschichte Studien zur Alten Geschichte Studien zur Alten Geschichte Studien zur Alten Geschichte Studien zur Alten Geschichte Studien zur Alten Geschichte Studien zur Alten Geschichte Studien zur Alten Geschi Studien Maintaining Peace and Interstate Stability in Archaic and Classical Greece Alten Geschichte Studien zur Alten Geschichte Studien zur Alten Geschichte Studien zur Alten schichte Studien zur Alten Geschichte Studien zur Alten Geschichte Studien zur Alten Geschichte Studien zur Alten Geschichte Studien zur Geschichte Studien zur Alten Geschichte Studien zur Alten Geschichte Studien zur Alten Geschichte Alten Geschichte Studien zur Alten Geschichte Studien zur Alten Geschichte Studien zur Alten Geschichte Studien zur Alten Geschichte Studien zur Alten Geschichte Studien zur Alten Geschichte Alten Geschichte Studien zur Alten Geschichte Studien zur Alten Geschichte -

The Ana Tomy of a Mercenary: from Archilochos to Alexander

THE ANA TOMY OF A MERCENARY: FROM ARCHILOCHOS TO ALEXANDER By Nicholas Fields Thesis submitted to the University of Newcastle upon Tyne in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy NEWCASTLE Ut4rVERSrT 4( LLRAR'( 094 51237 1 June 1994 To Leonidas THE ANA TOMY OF A MER CENA R Y.' FROM ARCHJLOCHOS TO ALEXANDER By Nicholas Fields ABSTRA CT Xenophon. who marched so many perilous Persian parasangs as a soldier-of-fortune and survived. has probably penned the most exciting, if not the best, memoirs by a mercenary to date. Moreover, for the military historian wishing to inquire into the human as well as the political aspects of hoplite- mercenary service, the Anabasis is the only in depth eye-witness account of an ancient Greek mercenary venture available. Of course the Anabasis is partisan and, at times, the contemporary reader cannot help but think that Xenophon's imagination is running away with him a bit. Nevertheless, his inside view of the complex relationships between mercenary-captains, the employers who employ them, the troops who follow them, the Spartans who use them, and those who mistrust them, has much more than just a passing value. Throughout mercenary history the balance between these groups has always been delicate, and, needless to say, the vicissitudes tend to follow the same pattern. Mercenary service was, and still is, a rather uncertain and dangerous vocation. We only have to read, for example, Colonel Mike bare's Congo memoirs to realise this. Apart from Xenophon himself and the mercenary-poet, Archilochos, the ancient literary sources generally supply little by way of data on such matters as recruitment, conditions of service, and the basic hopes, fears, and habits of those many individual hoplites who took up the mercenary calling as a way of life.