Helsinki Graffiti Subculture Meanings of Control and Gender in the Aftermath of Zero Tolerance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Moral Priorities of Rap Listeners

Published: Nzinga, K.L.K., & Medin, D.L. (2018). The Moral Priorities of Rap Listeners. Journal of Cognition and Culture, 312-342. http://booKsandjournals.brillonline.com/content/journals/10.1163/15685373-12340033 The Moral Priorities of Rap Listeners Kalonji L.K. NZINGA Douglas L. MEDIN Northwestern University A Cross-cultural approach to moral psychology starts from researchers withholding judgments about universal right and wrong and instead exploring community members’ values and what they subjeCtively perCeive to be moral or immoral in their loCal Context. This study seeks to identify the moral ConCerns that are most relevant to listeners of hip- hop music. We use validated psyChologiCal surveys inCluding the Moral Foundations Questionnaire (Graham, Haidt, & Nosek 2009) to assess whiCh moral ConCerns are most central to hip-hop listeners. Results show that hip-hop listeners prioritize concerns of justiCe and authentiCity more than non-listeners and deprioritize ConCerns about respeCting authority. These results show that the ConCept of the “good person” within the hip-hop subculture is fundamentally a person that is oriented towards soCial justiCe, rebellion against the status quo, and a deep devotion to keeping it real. Results are followed by a disCussion of the role that youth subCultures have in soCializing young people to prioritize Certain virtues over others as they develop their moral identity. 1. Introduction Many AmeriCan rappers inCluding KendriCk Lamar (2010), Snoop Dogg (2015), and Busta Rhymes (2006) have delivered the following CatCh phrase in their lyriCs: “You Can take me out the hood, but you Can’t take the hood out of me.” They proClaim that there are Certain aspeCts of the “hood” lifestyle and value system that, onCe they are part of you, direCt how you perCeive the world and behave in it. -

Breaking News: Ray Cried Again This Year

#6 Behold the face of the new lucky cat BREAKING NEWS: Editor’s RAY CRIED AGAIN Hello Corner THIS YEAR Alright dang so the wind is comin’ again and ACHEWOOD HEIGHTS, CA (MWY) — It makin’ blustery days which is all right for no longer changes the behavior of the stock walkin’ around and wonderin’. I think Fall is market, affects the moods of distant dogs, or the best weather for stone cold wondering. fills the many inches of this nation’s opinion You got your head down, feet all crunchin’ columns. That’s right— Ray Smuckles cried on crispy leaves, and bloosh a bluster blows a again, and for the first time in history, it few more past you. Hell of nice. If you want seems to have fallen on deaf ears. Except to get emo you can wear a scarf, but I rock it mine. old-school with just a real crap hoody that At approximately has a crackling MEINEKE TIRES logo nine thirty-two PM on across the chest. I don’t know where I got Sunday the twenty- it...I’m not even sure I got it. But it is usually fifth, I went up the around, and I put it on from time to time stairs to Mr. Smuckles’ when it gets this way, or if there is a late- private bedroom to night car trip. I find a long car trip is made announce the availabil- pretty nice by a thick hoody. Like that towel ity of a number of un- in HHGG. You got to have an accommodat- eaten pizza rolls. -

The Construction of Hip Hop Identities in Finnish Rap Lyrics Through English and Language Mixing

UNIVERSITY OF JYVÄSKYLÄ ”BUUZZIA, BUDIA JA HYVÄÄ GHETTOBOOTYA” - THE CONSTRUCTION OF HIP HOP IDENTITIES IN FINNISH RAP LYRICS THROUGH ENGLISH AND LANGUAGE MIXING A Pro Gradu Thesis in English by Elina Westinen Department of Languages 2007 HUMANISTINEN TIEDEKUNTA KIELTEN LAITOS Elina Westinen ”BUUZZIA, BUDIA JA HYVÄÄ GHETTOBOOTYA” - THE CONSTRUCTION OF HIP HOP IDENTITIES IN FINNISH RAP LYRICS THROUGH ENGLISH AND LANGUAGE MIXING Pro gradu –tutkielma Englannin kieli Joulukuu 2007 141 sivua Englannin kielen rooli ja asema maailmankielenä on kiistaton, ja Suomessakin englannin kieltä käytetään monilla eri aloilla. Juuriltaan amerikkalaisesta hip hop – kulttuuristakin on viime vuosina kasvanut globaali nuorisokulttuuri, joka on saavuttanut pysyvän aseman Suomessa. Tämän tutkimuksen tarkoituksena on selvittää, miten hip hop –identiteetti rakentuu suomalaisissa rap–lyriikoissa. Päätavoitteena on tutkia, millainen hip hop –identiteetti muodostuu lyriikoiden englannin kielen ja kielten sekoittumisen (suomi ja englanti) kautta. Tutkimuksen aineistona käytetään kolmen eri hip hop –artistin ja – ryhmän (Cheek, Sere & SP ja Kemmuru) lyriikoita 2000-luvulta. Niiden pääkieli on suomi, mutta kaikissa kappaleissa on myös englanninkielisiä elementtejä. Sanojen tarkkojen alkuperien sekä muun tiedon selvittämiseksi olen tarvittaessa konsultoinut itse artisteja. Analyysissä identiteetin käsitetään rakentuvan osaltaan kielen avulla. Identiteetti rakentuu diskursseissa, ja se on muuttuva ja monitahoinen. Aineiston analyysissä kielenvaihtelu ymmärretään joko a) kielten sekoittumisena, josta syntyy kokonaan uusi kieli/kielellinen tyyli tai b) koodinvaihtona, joka on merkityksellistä diskurssin paikallisella tasolla. Tulokset osoittavat, että rap–lyriikoissa pikemminkin sekoitetaan suomen ja englannin kieltä (language mixing) kuin vaihdetaan koodia. Näin ollen muodostuu uusi, suomalaisille rap–lyriikoille ominainen kieli ja tyyli. Usein hip hop -englannin sanoja ja fraaseja taivutetaan suomen ortografian, morfologian tai molempien mukaan. Joskus lyriikoissa esiintyy myös ns. -

January 2004 Issue of the SIX DEGREES-Magazine

FinlandsFinlands English English language language magazine magazine SixDegreesSixDegrees www.six-degrees.netwww.six-degrees.net IssueIssue 7/2003 1/2004 18.12.2003 28.1-24.2.2004 -27.1.2004 ������� ������ ������������������������������������������� � ������������������������������������������ ������������������������������������������������������ ��������������������������������������� ���������������������������������������������������� ������������������������������������������� ����������������������������������������������� ������������������������������������������� �������������������������������������������� ������������������������ ����������� �������� ���������� �������������������������������������������� ��������������������� ������������������������������������������� ����������� ������������ ������������������������������������������� ���������������� ������������������������������������������������ ������������������������������������������������ ����������������������������������������� ������������������������������������������� ����������������������������������������� ���������������������������� ���������������������������������������� ������������� ��������������������������������������������� ������������������������ �������� ���������������������������������������������� �������������������������������������� ������������������ �������������������� �������������� �������� ������������������������ ������������������ ��������������������� ����������� ��������� ������������������� ���� ������������ �������������� ����������������������� -

Arcturians: How to Heal, Ascend, and Help Planet Earth

Copyright © 2013 by David Miller All Rights Reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner without prior written permission from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and articles. The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this text via the Internet or via any other means without the permission of the publisher is illegal and punishable by law. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the author’s rights is appreciated. eISBN: 978-1-62233-687-6 Print Edition ISBN: 978-1-62233-002-7 Published and printed in the United States of America by: PO Box 3540 Flagstaff, AZ 86003 1-800-450-0985 1-928-526-1345 www.lighttechnology .com About the Book “We are at a crossroads in our spiritual evolution on Earth. This crossroads is called the point of ascension. Earth now has a tremendous number of ascended masters helping your planet transition into a higher light.” —Juliano, the Arcturians Go on a mind-expanding journey to explore new spiritual tools for dealing with our planetary crisis. Learn new healing techniques for rebalancing Earth. Study the groundbreaking concepts of between-lives therapy, and learn to release personal trauma so that you can proceed on your path to ascension. Included in this book are new and updated interpretations of the Kaballistic Tree of Life, which has now been expanded to embrace fifthdimensional planetary healing methods. Learn new and expanded Arcturian spiritual technologies, which include the concepts of shimmering, Biorelativity, and holographic healing methods. -

Planet Earth R Eco.R Din Gs

$4.95 (U.S.), $5.95 (CAN.), £3.95 (U.K.) IN THE NEWS ******** 3 -DIGIT 908 1B)WCCVR 0685 000 New Gallup Charts Tap 1GEE4EM740M09907411 002 BI MAR 2396 1 03 MON1 Y GREENLY U.K. Indie Dealers ELM AVE APT A 3740 PAGE LONG BEACH, CA 90807 -3402 8 Gangsta Lyric Ratings Discussed At Senate Hearing On Rap PAGE 10 THE INTERNATIONAL NEWSWEEKLY OF MUSIC, VIDEO AND HOME ENTERTAINMENT MARCH 5, 1994 ADVERTISEMENTS MVG's Clawfinger Grammy Nominations Spur Publicity Blitz Digs Into Europe Labels Get Aggressive With Pre Award Ads BY THOM DUFFY BY DEBORAH RUSSELL Clapton, and k.d. lang experienced draw some visibility to your artists." major sales surges following Gram- A &M launched a major television STOCKHOLM -The musical LOS ANGELES -As the impact of my wins, but labels aren't waiting for advertising campaign in late Febru- rage of Clawfinger, a rock-rap the Grammys on record sales has be- the trophies anymore. Several compa- ary to promote Sting's "Ten Sum- band hailing from Sweden, has come more evident nies have kicked off aggressive ad- moner's Tales," (Continued on page 88) in recent years, vertising and promotional campaigns which first ap- nominations, as touting their nominees for the March peared on The Bill- well as victories, 1 awards. board 200 nearly a have become valu- Says A &M senior VP of sales and year ago. Sting is able marketing distribution Richie Gallo, "It would the top- nominated evil oplriin tools for record seem that people are being more ag- artist in the 36th companies. -

9Rgrou / F BT Expra6s

f- r n r:l I h. l_ i U ll tl L L. I I l--.- a I "bt" transeau t I : 'q a I I l ? kl I \ € 7 I \ 0 T a I I F II I , L r ^ I \ l t XI ?ortv 9rgrou / F BT expra6s... I \ .a 12 I ! ! I ./ J L. I tl I n I I I a 1 / T / t f I , t I I - \ \ \ ,/ 7 ll 7 / E t / / WWW.EIEH'I, ,1LL.EtrIM TICHTO RAP HOUSE REGGAE ROCK DAIiCEHATL ACIO IUI{GLE AMBIEI{T II{OUSTRIAI- BHAIiGRA FREESTYI"E SOUI. fUI{K R&B LATIII IiI,tR o 'AZZ o alternativelndusttiol . bhongro . blues . dub. freestyle . hi-nry / house. iozzvibes . jungle.latin. rop. reggoe/dancehall remix poradiso . rock . techno music & business: take o ride on the bt express... prem um music zine: print * web I tl v f! t) \ I ) , I t a , ) 1 1 I' ! t I I --l t I E l = ti _) http : / /www.streetso u n d.co m Eorror.rn.orrrr richdmrnrlil*'t^Ll'^fl-t##fhHffiJt**nurr,*r.ro* o,,,"oo, t)ag (IuExTED,ToRS: lonnld.msrAP.<Lry.s !g'f.mll:rin ($htiff) S P.lnnrle BoG TECtltO. r Todd "Lrh" BlGe T!(H. L.dh tdno.& *O(t. b f!t|rlc! Ht.tPG. ocrnc. rd tDtlOa-AI-tARGE. trtrl.t flodtE SoUL flJ N( R&B.Syu.li Houde aLrtRNATlVt. B.mrd io6lit G FREESIYLE . Rody lrp..t xtE jU . SEwTCES ?.d E. top.E JAZZ VIEES . Ri.l Edl.i NGIE Cl.rl.s lftGlyrn REGGAE Dlrc & T.ry D.hopo los HOUSE lnita E( vldta BHANGRA Iln Frhry / lcI sn€graour{D u( .woorba ( coxla rS um$ | M.td and uiai 6olg. -

Shaggy Nice and Lovely Mp3, Flac, Wma

Shaggy Nice And Lovely mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Hip hop / Reggae Album: Nice And Lovely Country: UK & Europe Released: 1993 Style: RnB/Swing, Dancehall, Ragga MP3 version RAR size: 1626 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1741 mb WMA version RAR size: 1257 mb Rating: 4.2 Votes: 417 Other Formats: XM MPC MIDI MP4 TTA MP3 WMA Tracklist Hide Credits Nice And Lovely (Radio Edit) 1 3:26 Producer – Sting International Nice And Lovely (Moore R&B Mix) 2 4:32 Producer – Errol Moore Oh Carolina (Konders Flatbush Mix) 3 4:28 Producer – Bobby Konders 'Fraid To Ask 4 3:58 Producer – Lloyd CampbellRemix – Sting International Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Nice And Lovely Virgin Records Y-38420 Shaggy Y-38420 US 1993 (12") America, Inc. SHAGGY Nice And Lovely Greensleeves SHAGGY Shaggy UK 1993 PROMO 1 (12", Promo) Records PROMO 1 Shaggy Shaggy Featuring S7-17599 Featuring Virgin S7-17599 US 1993 Rayvon - Nice Rayvon And Lovely (7") Nice And Lovely Greensleeves GRED 405 Shaggy GRED 405 UK 1993 (12") Records Virgin Records Nice And Lovely DPRO 14199, America, Inc., DPRO 14199, Shaggy (CD, Single, US 1993 DPRO-14199 Virgin Records DPRO-14199 Promo) America, Inc. Related Music albums to Nice And Lovely by Shaggy Shaggy Featuring Brian & Tony Gold - Hey Sexy Lady Sting & Shaggy - Don't Make Me Wait (Tom Stephan ALTERNATE Remix) Shaggy 2 Dope - F.T.F.O.M.F. Shaggy Featuring Grand Puba - Why You Treat Me So Bad Shaggy - The Essential Shaggy Featuring Ricardo "Rikrok" Ducent - It Wasn't Me Shaggy featuring Marsha - Piece Of My Heart Shaggy Feat Shhhean - Boom Boom Shaggy - Original Doberman Shaggy / Stevie Wonder / Big Punisher - Greatest Hits. -

WARNER BROS. / WEA RECORDS 1970 to 1982

AUSTRALIAN RECORD LABELS WARNER BROS. / WEA RECORDS 1970 to 1982 COMPILED BY MICHAEL DE LOOPER © BIG THREE PUBLICATIONS, APRIL 2019 WARNER BROS. / WEA RECORDS, 1970–1982 A BRIEF WARNER BROS. / WEA HISTORY WIKIPEDIA TELLS US THAT... WEA’S ROOTS DATE BACK TO THE FOUNDING OF WARNER BROS. RECORDS IN 1958 AS A DIVISION OF WARNER BROS. PICTURES. IN 1963, WARNER BROS. RECORDS PURCHASED FRANK SINATRA’S REPRISE RECORDS. AFTER WARNER BROS. WAS SOLD TO SEVEN ARTS PRODUCTIONS IN 1967 (FORMING WARNER BROS.-SEVEN ARTS), IT PURCHASED ATLANTIC RECORDS AS WELL AS ITS SUBSIDIARY ATCO RECORDS. IN 1969, THE WARNER BROS.-SEVEN ARTS COMPANY WAS SOLD TO THE KINNEY NATIONAL COMPANY. KINNEY MUSIC INTERNATIONAL (LATER CHANGING ITS NAME TO WARNER COMMUNICATIONS) COMBINED THE OPERATIONS OF ALL OF ITS RECORD LABELS, AND KINNEY CEO STEVE ROSS LED THE GROUP THROUGH ITS MOST SUCCESSFUL PERIOD, UNTIL HIS DEATH IN 1994. IN 1969, ELEKTRA RECORDS BOSS JAC HOLZMAN APPROACHED ATLANTIC'S JERRY WEXLER TO SET UP A JOINT DISTRIBUTION NETWORK FOR WARNER, ELEKTRA, AND ATLANTIC. ATLANTIC RECORDS ALSO AGREED TO ASSIST WARNER BROS. IN ESTABLISHING OVERSEAS DIVISIONS, BUT RIVALRY WAS STILL A FACTOR —WHEN WARNER EXECUTIVE PHIL ROSE ARRIVED IN AUSTRALIA TO BEGIN SETTING UP AN AUSTRALIAN SUBSIDIARY, HE DISCOVERED THAT ONLY ONE WEEK EARLIER ATLANTIC HAD SIGNED A NEW FOUR-YEAR DISTRIBUTION DEAL WITH FESTIVAL RECORDS. IN MARCH 1972, KINNEY MUSIC INTERNATIONAL WAS RENAMED WEA MUSIC INTERNATIONAL. DURING THE 1970S, THE WARNER GROUP BUILT UP A COMMANDING POSITION IN THE MUSIC INDUSTRY. IN 1970, IT BOUGHT ELEKTRA (FOUNDED BY HOLZMAN IN 1950) FOR $10 MILLION, ALONG WITH THE BUDGET CLASSICAL MUSIC LABEL NONESUCH RECORDS. -

'Bättre Folk' – Critical Sociolinguistic Commentary in Finnish Rap Music

Paper ‘Bättre folk’ – Critical Sociolinguistic Commentary in Finnish Rap Music by Elina Westinen (University of Jyväskylä) December 2011 ‘Bättre folk’ – Critical Sociolinguistic Commentary in Finnish Rap Music Elina Westinen Description Westinen, Elina, MA, is a doctoral student in the Center of Excellence for the Study of Variation, Contacts and Change in English (VARIENG), funded by the Academy of Finland (2006-2011) and in the Languages and Discourses in Social Media research team which is part of the Max Planck Working Group on Sociolinguistics and Superdiversity. In her ongoing PhD study, she is exploring the construction of polycentric authenticity in Finnish hip hop culture through linguistic and discursive repertoires on several scale-levels. Her research relates to the following research areas: sociolinguistics, discourse studies, multilingualism and hip hop research. Summary This paper discusses the ways in which rap music makes use of a range of resources to construct a critical sociolinguistic commentary. The specific case it focuses on is Finnish rap which takes issue with the official, but often tension-ridden Finnish-Swedish bilingualism in Finland. It shows how the resources used in this kind of rap are simultaneously discursive and linguistic and how they operate on several scale-levels, i.e. socio-temporal frames (Blommaert 2010), such as global, translocal and local. The findings of this paper will contribute to our understanding of (trans)local hip hop cultures and, more specifically, of the versatile nature of Finnish rap music. In my analysis, I will look into the ways in which a local rapper creates a sociolinguistic critique by making use of both discursive and linguistic resources. -

Chicago Jazz Festival Spotlights Hometown

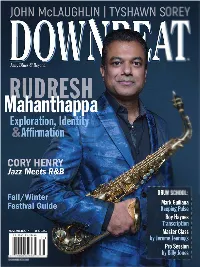

NOVEMBER 2017 VOLUME 84 / NUMBER 11 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Managing Editor Brian Zimmerman Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Markus Stuckey Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Hawkins Editorial Intern Izzy Yellen ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Kevin R. Maher 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. Jackson, Jimmy Katz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Richard Seidel, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian, -

2 Records Aug 15 2021

Sept 2, 2021 Latest additions indicated by asterisk (*) C * ? & THE MYSTERIANS 99 TEARS / MIDNIGHT HOUR 10 CC I'M NOT IN LOVE/CHANNEL SWIMMER 1910 FRUITGUM CO, SIMON SAYS REFLECTIONS FROM THE LOOKING GLASS 1910 FRUITGUM CO. SIMON SAYS/REFLECTIONS FROM THE LOOKING GLASS 2 R 1910 FRUITGUM CO. INDIAN GIVER / POW WOW 3 SHARPES QUARTET LES MY LOVE WAS NOT TRUE LOVE/BELLE ST. JOHN R 49TH PARALLEL NOW THAT I'M A MAN / TALK TO ME R 6 CYLINDER AIN'T NOBODY HERE BUT US CHICKENS / STRONG WOMAN.... 6 CYLINDER AIN'T NOBODY HERE BUT US CHICKENS / STRONG WOMAN'S LOVE 8TH DAY IF I COULD SEE THE LIGHT / IF I COULD SEE THE LIGHT (INST) 9 LAFALCE BROTHERS MARIA, MARIA, MARIA/THE DEVIL'S HIGHWAY A TASTE OF HONEY SUKAYAKI / DON'T YOU LEAD ME ON A*TEENS DANCING QUEEN / MAMMA MIA A*TEENS DANCING QUEEN / MAMMA MIA AARON LEE ONLY HUMAN / EMPTY HEART A * ABBA KNOWING ME KNOWING YOU / HAPPY HAWAII A * ABBA MONEY MONEY MONEY / CRAZY WORLD ABBOTT GREGORY SHAKE YOU DOWN / WAIT UNTIL TOMORROW ABBOTT RUSS SPACE INVADERS MEET PURPLE PEOPLE EATER/COUNTRY COOPERMAN ABC ALL OF MY HEART / OVERTURE ABC ALL OF MY HEART / OVERTURE ABC THAT WAS THEN BUT THIS IS NOW / VERTIGO ABC THE LOOK OF LOVE / THE LOOK OF LOVE ABDUL PAULA MY LOVE IS FOR REAL / SAY I LOVE YOU ABDUL PAULA I DIDN'T SAY I LOVE YOU/MY LOVE IS FOR REAL ABDUL PAULA IT'S JUST THE WAY YOU LOVE ME/DUB MIX . PICTURE SLEEVE ABDUL PAULA THE PROMISE OF A NEW DAY/THE PROMISE OF A NEW DAY ABDUL PAULA VIBEOLOGY/VIBEOLOGY ABRAMS MISS MILL VALLEY/THE HAPPIEST DAY OF MY LIFE ABRAMSON RONNEY NEVER SEEM TO GET ALONG WITHOUT YOU/TIME