Working Papers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

180203 the Argentine Military and the Antisubversivo Genocide

Journal: GSI; Volume 11; Issue: 2 DOI: 10.3138/gsi.11.2.03 The Argentine Military and the “Antisubversivo” Genocide DerGhougassian and Brumat The Argentine Military and the “Antisubversivo ” Genocide: The School of Americas’ Contribution to the French Counterinsurgency Model Khatchik DerGhougassian UNLa, Argentina Leiza Brumat EUI, Italy Abstract: The article analyzes role of the United States during the 1976–1983 military dictatorship and their genocidal counterinsurgency war in Argentina. We argue that Washington’s policy evolved from the initial loose support of the Ford administration to what we call “the Carter exception” in 1977—79 when the violation of Human Rights were denounced and concrete measures taken to put pressure on the military to end their repressive campaign. Human Rights, however, lost their importance on Washington’s foreign policy agenda with the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979 and the end of the Détente. The Argentine military briefly recuperated US support with Ronald Reagan in 1981 to soon lose it with the Malvinas War. Argentina’s defeat turned the page of the US support to military dictatorships in Latin America and marked the debut of “democracy promotion.” Keywords: Proceso, dirty war, human rights, Argentine military, French School, the School of the Americas, Carter Page 1 of 48 Journal: GSI; Volume 11; Issue: 2 DOI: 10.3138/gsi.11.2.03 Introduction: Framing the US. Role during the Proceso When an Argentine military junta seized the power on March 24, 1976 and implemented its “ plan antisubversivo ,” a supposedly counterinsurgency plan to end the political violence in the country, Henry Kissinger, the then United States’ Secretary of State of the Gerald Ford Administration, warned his Argentine colleague that the critiques for the violation of human rights would increment and it was convenient to end the “operations” before January of 1977 when Jimmy Carter, the Democratic candidate and winner of the presidential elections, would assume the power in the White House. -

Five Years of People's

44 Excerpts from Worldwide Compoign Speech Five Yeqrs of People's Wqr I I a Following ore excerpts {rom the political power: revolutionary carried out in our homeland by the I moin speech given ot meetings held violence. The theory of seizing Peruvian people and the Communist oround the power peaceful road is guided 'Irorld os port"of the by the wrong, Party of Peru, by the invin- Worhwide Compoign to Support impracticable and revisionist. cible banners of Marxism-Leninism- i= the People's Wor in Peru. The Revolution is the overthrow of one Maoism, Guiding Thought of speech wos prepored by o Peru- class by another and the old classes Chairman Gonzalo. I vion living obrood who closely will never give up their political Let's look at some historical a { follows events in Peru. -AWTW power voluntarily, not even in the background. c worst crisis. The only way to deal The Communist Party of Peru, o SUMMING UP FIVE YEARS OF with them is to sweep them away the PCP, was reconstituted as a Par- i PEOPLE'S WAR IN PERU AND through revolutionary war, by ty of a new type, based on Marxism- THE CURRENT POLITICAL means of revolutionary armed force. Leninism-Maoism, Guiding SITUATION We should keep this universally Thought of Chairman Gonzalo, in valid principle in mind. other words, as a fighting machine PART ONE: SUMMATION OF We should also keep in mind one and not just an organising machine. FIVE YEARS OF PEOPLE'S of Marx's great teachings: If this hadn't been done, it would WAR "Once the banner of revolution is have been impossible to make raised, it cannot be lowered again." revolution. -

Administration of Justice in Latin America Is Facing Its Gravest Crisis As It Is Perceived As Unable to Respond to Popular Demands

ADMINISTRATION OF JUSTICE IN LATIN AMERICA A PRIMER ON THE CRIMINAL JUSTICE SYSTEM LUIS SALAS & JOSE MARIA RICO CENTER FOR THE ADMINISTRATION OF JUSTICE FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY 1993 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION 1 I. THE GENERAL CONTEXT 3 A. History 3 1. Conquest and Colonization 3 2. Independence 5 3. Twentieth Century 6 B. Crime 8 C. The Civil Law Model 9 II. LEGISLATION 12 III. POLICE 14 IV. PROSECUTION 18 V. LEGAL DEFENSE 22 VI. COURTS 25 A. Court Organization 25 B. Court Administration 27 C. Selection and Tenure 28 D. Background of Judges 31 VII. CORRECTIONS 33 VIII. CRIMINAL PROCEDURE 36 A. Types of Procedures 36 B. Fundamental Guarantees 36 C. The Stages of the Process 37 1. The Instructional or Summary Stage 38 2. The Trial 40 3. Appellate remedies 40 D. Duration and Compliance with Procedural Periods 41 IX. PROBLEMS FACING THE ADMINISTRATION OF JUSTICE 42 A. General Problems 42 1. Norms 42 2. Social and Economic Problems 43 3. Political Problems 44 4. Human Rights 45 B. Judicial Independence 46 1. Unification of the Judicial Function 47 2. Judicial Career 48 C. Justice System Access 49 1. Knowledge of Rights and Institutions 49 2. Confidence 50 3. Costs 50 4. Location and Number of Courts 50 5. Corruption 50 D. Efficiency 51 1. Administration 51 2. Coordination 52 3. Budgeting, Planning and Evaluation 52 4. Caseloads and Delays 52 E. Fairness 53 F. Accountability 54 Glossary of Spanish Terms Used 56 Suggested Readings 59 Page TABLES 1. Issuance Dates of Current Latin American Constitutions and Codes 13 2. -

Critique of Maoist Reason

Critique of Maoist Reason J. Moufawad-Paul Foreign Languages Press Foreign Languages Press Collection “New Roads” #5 A collection directed by Christophe Kistler Contact – [email protected] https://foreignlanguages.press Paris 2020 First Edition ISBN: 978-2-491182-11-3 This book is under license Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-SA 4.0) https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/ Contents Introduction 1 Chapter 1 The Route Charted to Date 7 Chapter 2 Thinking Science 19 Chapter 3 The Maoist Point of Origin 35 Chapter 4 Against Communist Theology 51 Chapter 5 The Dogmato-eclecticism of “Maoist Third 69 Worldism” Chapter 6 Left and Right Opportunist Practice 87 Chapter 7 Making Revolution 95 Conclusion 104 Acknowledgements 109 Introduction Introduction In the face of critical passivity and dry formalism we must uphold our collective capacity to think thought. The multiple articulations of bourgeois reason demand that we accept the current state of affairs as natural, reducing critical thinking to that which functions within the boundaries drawn by its order. Even when we break from the diktat of this reason to pursue revolutionary projects, it is difficult to break from the way this ideological hegemony has trained us to think from the moment we were born. Since we are still more-or-less immersed in cap- italist culture––from our jobs to the media we consume––the training persists.1 Hence, while we might supersede the boundaries drawn by bourgeois reason, it remains a constant struggle to escape its imaginary. The simplicity encouraged by bourgeois reasoning––formulaic repeti- tion, a refusal to think beneath the appearance of things––thus finds its way into the reasoning of those who believe they have slipped its grasp. -

The Role of Portugal's Armed Forces Movement GONCALVES: Military "Savior" Is Using CP to Discredit All Political Parties

Europe Oceonio the Americas Vol. 13, No. 21 < 1975 by Intercontinental Press June 2, 1975 News Analysis The Seizure of ^Republica' —A Bad Omen V m\^ Livio Mafton The Role of Portugal's Armed Forces Movement GONCALVES: Military "savior" is using CP to discredit all political parties. Cubans Hail Vietnamese Triumph Muss Pressure on the Rise in Lues More on Evacuation of Cambodia's Cities Indian Maoists Criticize Peking the streets. Even such limited shows of force, however, can quickly get out of hand, as the confrontation at the Republica offices has again shown. It was obvious after the May Day clashes The Seizure of 'Republica'—a Bad Omen that the Intersindical congress scheduled for the end of May would entail a major confrontation between the two reformist The government of the Armed Forces of their alliance with the SP. The author workers parties. The SP offensive in the Movement took a major step toward "insti claimed that the Chinese leaders realized mass media is also linked to an offensive in tutionalizing" a populist military dictator that the SP was the only effective alterna the journalists union. It was equally obvi ship May 20 when it took advantage of a tive to the pro-Moscow party. ous that the CP intended to preserve its Communist party power grab to silence The New York Times editors said that the bureaucratic positions in the unions at all Republica, the Lisbon daily most closely move against Republica came "after Mr. cost. This was what led the Stalinists to linked to the Socialist party leadership. -

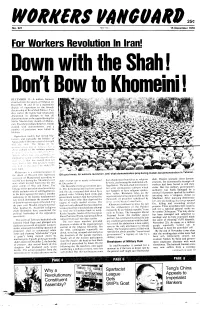

For Workers Revolution in Iran! • Ownwi E a I• On'l 60W to Omeinil

WfJRNERI IIIIN(JIJIIR' 25¢ No. 221 :~~~ X-523 15 December 1978 For Workers Revolution In Iran! • ownwi e a I• on'l 60W to omeinil DECE M BER U~A million Iranians streamed into the streets of Teheran on December 10 and II in a mammoth displav of opposition to the bloody dictatorship of Renl Shah Pahlavi. Two days earlier thc regime had reluctantly abandoned its attempt to ban all demonstrations in the capital during the Shi'ite Muslim holy month of M uhar ram. Elsewhere in Iran, however, troops clashed with demonstrators, and a number of protesters were killed in Isla\nn. Opposition kaders had turned Mu hdrr~tm and especially the holiday of \shura (the II th) into a test of strength \\'itr: ttll' ,hah -rhc liftln~ (If the O~;:I(i;l~-.:i~\tiC!11 hJIl in l~hC'~'~;,l \\d d. "h:!rr :-;,,'[h:ick to rhe mihtary govern.... l"'.'. i~ :-: (j~\".i~'1n p /:' \/h.~l:. \\ !-:lL h h~t" ~ln:~,l.;.:c~sstul\~, ~\1~_ \L.~rnp .'!na~~,l\C ft.' f11 r fl'lI to ',Hll tilL" dnll- "(',.:, .<.\ " tint ha, f"l)Cked Iran for r~'\.'r~ thl:r!.l :". \ t1c nc\.t fc\\,' \\cck' \ ,,\cll "',_'''.' tiL' Cltd I..\f t!li: sh(-d"l~S 25- \ l';l r rel,l:!1. Setboun/S!Da Muharram is it commemoration of Off your knees, for workers revolution. Anti-shah demonstrators pray during mullah-led demonstration in Teheran. the death of HLhsein (the legitimate successor of Muhammed according to shah. Despite sporadic street demon the Shi'itesl during the 7th century ci\il shah', troops ran to nearly a thousand had abandoned themselves to religious strations, the economically strategic oil \\ars \\hich di\lded Islam into the two hysteria. -

The Crisis of the Chilean Socialist Party (Psch) in 1979

UNIVERSITY OF LONDON 1 1 INSTITUTE OF LATIN AMERICAN STUDIES WORKING PAPERS The Crisis of the Chilean Socialist Party (PSCh) in 1979 Carmelo Furci The Crisis of the Chilean Socialist Party (PSCh) in 1979 Carmelo Furci Honorary Research Fellow Institute of Latin American Studies, London University of London Institute of Latin American Studies 31 Tavistock Square, London WC1H 9HA Editorial Committee Dr. George Philip Dr. Leslie Bethell Miss Daphne Rodger ISBN 0 901145 56 4 ISSN 0142-1875 THE CRISIS OF THE CHILEAN SOCIALIST PARTY (PSCh) IN 1979* Introduction After Chile's military coup of September 1973, the Partido Socialista de Chile (PSCh) almost disintegrated; and the disputes of the various underground centres that emerged after the coup did not help to restore the credibility of the party. By 1979, through a series of splits, expulsions, and disagreements between the organisation underground in Chile and the segment of the party in exile, the PSCh went through the most serious crisis of its history, which had already been dominated by many divisions and disagreements over its political strategy. From 1979 to the present, the existence of a variety of Socialist 'parties', with only one having a solid underground apparatus in Chile — the PSCh led by Clodomiro Almeyda, former Foreign Secretary of Allende — prevented a more successful and effective unity of the Chilean left, and thus a more credible political alternative of power to the military regime of General Pinochet. This paper will focus on the process that took the PSCh to its deepest crisis, in 1979, attempting a reconstruction of the schisms and disputes in organisational as well as political terms and an explanation of the reasons behind them. -

A Socialist Program

DECEMBER 28, 1973 25 CENTS VOLUME 37/NUMBER 48 A SOCIALIST NEWSWEEKLY/PUBLISHED IN THE INTERESTS OF THE WORKING PEOPLE A socialist program · Socialist convicted in frame-up/7 · Defend the ~ttica Brothers'/10 In Brief PUERTO RICO A COLON:Y, UN SAYS: A victory was and .Hellenic-American Society held a teach-in at Indiana scored by the movement favoring independence for Puerto University at Bloomington. Speakers included Nick Pet THIS Rico when the United Nations voted to declare the island ro,poulos, professor of sociology at Indiana University a U.S. colony. Purdue University at Indianapolis (IUPUI), and George WEEK'S The resolution, initially adopted by the UN Committee Lianis, professor of engineering at Purdue and a graduate for Decolonization, reaffirms the "inalienable right of the of Athens Polytechnic University. An editorial based on Puerto Rican people to self-determination and indepen their talks appeared in the campus dally two days later MILITANT dence." Discussion and a vote on the resolution, which entitled "Greece: Apparently a U.S. Engineered Coup." has been put offfor some time under pressure from Wash The following day, the two speakers appeared at a 6 British gov't imposes ington, came after strong protests by the Cuban ambas similarly sponsored teach-in at IUPUI. harsh antilabor policies sador, Ricardo Alarcon. The vote on the committee's 8 Kissinger lied about role report was 104 in favor and 5 against, with 19 absten in setting up 'plumbers' tions. Voting against were France, Britain, South Africa, 'HUMANITARIAN' AWARD: A picket line was held Dec. 9 Outrage over secret FBI Portugal, and the U.S., which objected to it as an intrusion 8 in front of the Olympic Hotel in Seattle to protest the into the "internal affairs" of the U.S. -

The Economic Legacy of General Velasco: Long-Term Consequences of Interventionism

The Economic Legacy of General Velasco: Long-Term Consequences of Interventionism C´esarMartinelli∗ Marco Vegay December 9, 2019 Abstract We apply synthetic control methods to study the long-term consequences of the interven- tionist and collectivist reforms implemented by the Peruvian military junta of 1968{1975. We compare long-term outcomes for the Peruvian economy following the radical reforms of the early 1970s with those of two controls made of similar countries, one chosen in the Latin American region and another one chosen from the world at large. We find that the economic legacy of the junta includes sizable loses in GDP along two decades, beyond those that can be attributed to adverse international circumstances. The evidence suggests that those loses can be attributed both to a decline in capital accumulation and to a fall in productivity. Keywords: Output loss, synthetic controls, military nationalism, populism, collectivism, Peru- vian Revolution JEL codes: E52, E58, E62 ∗George Mason University, [email protected] (corresponding author) yBanco Central de Reserva del Per´uand Universidad Cat´olicadel Per´u, [email protected] We thank Roxana Barrantes, Roberto Chang, Alberto Chong, Kevin Grier, Gonzalo Pastor, Silvio Rend´on, Bruno Seminario, and three anonymous referees for helpful comments. The authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this paper. 1 Introduction The Peruvian military junta, presided by General Velasco from 1968 to 1975, represents a very unusual experiment in economic policy. The military engaged in a wide range of reforms restructuring ownership of economic assets in favor of the public sector and generally increasing the role of the state in the economy. -

SPLIT RANKS of WORKERS I in PORTUGAL

Intercontinental Press Africa Asia Europe Oceania the Americas Vol. 13, No. 29 ' 1975 by Intercontinental Press July 28, 1975 STALINISTS SPLIT RANKS OF WORKERS i IN PORTUGAL Workers Press CARVALHO: General on a white horse? Angolans on Brink of Civil War other Articles Demands Mount for Ouster of Peron GiA: 20 Years of Spying on SWP 100,000 in Madras Protest Gandfil's Coup The Famine in Haiti Zionists Step Up Coionization of West Bank iranian CP Hails Shah's Betrayal of Kurds What Happened to Cambodia's Cities? Free the Political Prisoners in Dominica! important, the United States and its NATO allies need to make it plain to Moscow that the Soviet Union will be held responsible if Portugal's Communists continue on their ,;* present path and that the West's democracies cannot accept imposition of Communism there by force or subversion." So, the Times recommended keeping a Portugal: The Imperialists Play a Waiting Game wary eye on the Portuguese CP and Moscow but did not raise an alarm or begin to prepare the American public for "drastic action." Throughout the third week in July, most more by the attempts of the Stalinists and Some columnists thought that even if the commentators in the international capitalist ultralefts to identify socialism with dictator worst happened, it would be no disaster. press were speculating that a "Communist ship, it would presumably be easier to offer Clayton Fritchey said in the July 17 New take-over" could be imminent in Portugal. aid "with strings of democracy." York Post: But they did not seem to get very excited If one of the most authoritative voices of "Portugal may or may not go Marxist, but about it. -

Redalyc.ITALY, the UNO and the INTERNATIONAL CRISES

UNISCI Discussion Papers ISSN: 1696-2206 [email protected] Universidad Complutense de Madrid España Tosi, Luciano ITALY, THE UNO AND THE INTERNATIONAL CRISES UNISCI Discussion Papers, núm. 25, enero, 2011, pp. 77-123 Universidad Complutense de Madrid Madrid, España Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=76717367006 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative UNISCI Discussion Papers, Nº 25 (January / Enero 2011) ISSN 1696-2206 ITALY, THE UNO AND THE INTERNATIONAL CRISES Luciano Tosi 1 University of Perugia Abstract: In post-war Italy, the refusal of nationalism and the aspiration to a policy of international cooperation both at the European and world level were widely shared. At the Potsdam conference American President Truman proposed to admit Italy to UNO, however, this was met with Soviet opposition. In the context of the Cold War, Italy entered the UNO in 1955, together with other 15 countries. At the UNO, Italy‘s performance, for example on decolonization issues, was conditioned by her links with the USA, by the membership of the Western bloc and by her economic interests. Italy recognised Communist China only in 1970 and in 1971 voted for its admission to the UNO. In 1969 Prime Minister Moro described at the UN General Assembly a «global strategy of maintaining peace», a manifesto of a détente based on the UNO and on the equality of states as opposed to the «concert of powers». -

The Surrender of Odio De Clase, Abandoning Maoism

Encyclopedia of Anti-Revisionism On-Line * Spain lesmaterialistes.com The surrender of Odio de Clase, abandoning Maoism First Published: April 1st 2014 Transcription, Editing and Markup: Sam Richards and Paul Saba Copyright: This work is in the Public Domain under the Creative Commons Common Deed. You can freely copy, distribute and display this work; as well as make derivative and commercial works. Please credit the Encyclopedia of Anti-Revisionism On-Line as your source, include the url to this work, and note any of the transcribers, editors & proofreaders above. In his last article, the Odio de Clase collective from Spain has put the mask away. It upholds Marxism-Leninism, and not Maoism any more. It is a jump in the capitulation before the Spanish tradition of “Marxism-Leninism” in a mix of Hoxhaism and revisionism, economist “redskins” culture and cult of the 1930's, “anti- imperialism” in the form of anti-americanism. It is also a jump which is, indeed, not a surprise for anyone disappointed by this Collective (see Odio de Clase's way to relativism and centrism). In the past, it informed a lot about Maoist organizations in the world, it played a very positive role, serving as an intermediary between Maoist structures. The situation turned nevertheless in its contrary, because the Collective was incapable to analyze its own country in a dialectical materialist way. Therefore, images of Stalin replaced the content, anti- imperialism became a strategy and an identity. In fact, the more the economical crisis deepened in Spain, the less the Collective was able to deal with it.