1 I. a Nexus Between Nepali Nationalism and Ethnic Mode Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Language Politics and State Policy in Nepal: a Newar Perspective

Language Politics and State Policy in Nepal: A Newar Perspective A Dissertation Submitted to the University of Tsukuba In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in International Public Policy Suwarn VAJRACHARYA 2014 To my mother, who taught me the value in a mother tongue and my father, who shared the virtue of empathy. ii Map-1: Original Nepal (Constituted of 12 districts) and Present Nepal iii Map-2: Nepal Mandala (Original Nepal demarcated by Mandalas) iv Map-3: Gorkha Nepal Expansion (1795-1816) v Map-4: Present Nepal by Ecological Zones (Mountain, Hill and Tarai zones) vi Map-5: Nepal by Language Families vii TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents viii List of Maps and Tables xiv Acknowledgements xv Acronyms and Abbreviations xix INTRODUCTION Research Objectives 1 Research Background 2 Research Questions 5 Research Methodology 5 Significance of the Study 6 Organization of Study 7 PART I NATIONALISM AND LANGUAGE POLITICS: VICTIMS OF HISTORY 10 CHAPTER ONE NEPAL: A REFLECTION OF UNITY IN DIVERSITY 1.1. Topography: A Unique Variety 11 1.2. Cultural Pluralism 13 1.3. Religiousness of People and the State 16 1.4. Linguistic Reality, ‘Official’ and ‘National’ Languages 17 CHAPTER TWO THE NEWAR: AN ACCOUNT OF AUTHORS & VICTIMS OF THEIR HISTORY 2.1. The Newar as Authors of their history 24 2.1.1. Definition of Nepal and Newar 25 2.1.2. Nepal Mandala and Nepal 27 Territory of Nepal Mandala 28 viii 2.1.3. The Newar as a Nation: Conglomeration of Diverse People 29 2.1.4. -

Everything I Learned About Nepali Literature Is Wrong | 217

(ALMOST) EVERYTHING I LEARNED ABOUT NEPALI LITERATURE IS WRONG | 217 Chautari Foundation Lecture 2018 (ALMOST) EVERYTHING I LEARNED ABOUT NEPALI LITERATURE IS WRONG Manjushree Thapa I’ve been rethinking my sense of Nepali literature, and am pleased to have a chance to share my thoughts at Martin Chautari, an organization that I played a very small role in founding back in the 1990s, when it was an informal discussion group among “development” workers.1 Most of us, at the time, were foreign-educated, or actual foreigners. We were well meaning, but we were seeking an intellectual life without any links to Nepal’s own intellectual traditions in the political parties, the universities, the writers and activists. It was particularly under Pratyoush Onta’s leadership that Martin Chautari developed these links and became a site where foreign-educated Nepalis, foreigners, and Nepal’s own intellectual traditions could meet for open debate. Knowledge-generation is a collective enterprise. It is not an endeavor a person undertakes in isolation. I’ve written and spoken before on the thoughts I’ll share here, first in the introduction (Thapa 2017a) to La.Lit, A Literary Magazine Volume 8 (Special issue: Translations from the Margins), which I edited (Thapa 2017b), and then at two talks for the Himalayan Studies Conference at the University of Colorado, in Boulder, in September 2017, and for the Nepal Studies Initiative at the University of Washington, in Seattle, in April 2018. This lecture is a crystallizing of those thoughts, which are still in formation. One caveat: I am not a scholar, but a writer; I am engaged in what Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak calls the “wild practice” (2012: 394). -

Devkota's Voice of Rebellion and Social Critique in the Lunatic

© IJARW | ISSN (O) - 2582-1008 April 2020 | Vol. 1 Issue. 10 www.ijarw.com DEVKOTA’S VOICE OF REBELLION AND SOCIAL CRITIQUE IN THE LUNATIC Dr. Ramesh Prasad Adhikary Assistant Professor, Tribhuwan University, Kathmandu, M.M. Campus, Nepalgunj, Nepal ABSTRACT The present research paper explores Laxmi Prasad Devkota’s use of nonconformist theme and style in his seminal poem The Lunatic. His nonconformist theme and his style challenge the traditional values and norms prevailing in the contemporary society. The poet develops his consciousness of change and antitraditional view against the contemporary society in his poem The Lunatic. He challenges the contemporary traditional social norms, systems and values in order to flow his consciousness of change and progress. Devkota is against the traditional Rana regime and advocated for consciousness of change, progress and democracy in his literary work. Keyword: Descent voice, nonconformist theme, social rebellion, modernity, voice for freedom 1. INTRODUCTION DEVKOTA AS A DISSENT consciousness of his age that’s why to change the AND REBELLIOUS POET age from the poverty, injustice, emptiness and domination; he sees the bullets power rather than The Lunatic presents Devkota’s anger and satire other. Only revolution and bullets can be the over the-then society. In his poems, he protests all suitable solutions to these problems. In his poems, contemporary traditional and religion oriented Devkota tries to inspire all the Nepalese people to rules, values and system. Devkota introduces change the thinking, morality and behavior many anti-traditional themes from the according to the age. contemporary society in his poem. He deals with the themes like domination, poverty, employment, Moreover, Devkota passed his life under the rules and hunger and education system of Nepal. -

Chemjong Cornellgrad 0058F

“LIMBUWAN IS OUR HOME-LAND, NEPAL IS OUR COUNTRY”: HISTORY, TERRITORY, AND IDENTITY IN LIMBUWAN’S MOVEMENT A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Dambar Dhoj Chemjong December 2017 © 2017 Dambar Dhoj Chemjong “LIMBUWAN IS OUR HOME, NEPAL IS OUR COUNTRY”: HISTORY, TERRITORY, AND IDENTITY IN LIMBUWAN’S MOVEMENT Dambar Dhoj Chemjong, Ph. D. Cornell University 2017 This dissertation investigates identity politics in Nepal and collective identities by studying the ancestral history, territory, and place-naming of Limbus in east Nepal. This dissertation juxtaposes political movements waged by Limbu indigenous people with the Nepali state makers, especially aryan Hindu ruling caste groups. This study examines the indigenous people’s history, particularly the history of war against conquerors, as a resource for political movements today, thereby illustrating the link between ancestral pasts and present day political relationships. Ethnographically, this dissertation highlights the resurrection of ancestral war heroes and invokes war scenes from the past as sources of inspiration for people living today, thereby demonstrating that people make their own history under given circumstances. On the basis of ethnographic examples that speak about the Limbus’ imagination and political movements vis-à-vis the Limbuwan’s history, it is argued in this dissertation that there can not be a singular history of Nepal. Rather there are multiple histories in Nepal, given that the people themselves are producers of their own history. Based on ethnographic data, this dissertation also aims to debunk the received understanding across Nepal that the history of Nepal was built by Kings. -

Nepalese Translation Volume 1, September 2017 Nepalese Translation

Nepalese Translation Volume 1, September 2017 Nepalese Translation Volume 1,September2017 Volume cg'jfbs ;dfh g]kfn Society of Translators Nepal Nepalese Translation Volume 1 September 2017 Editors Basanta Thapa Bal Ram Adhikari Office bearers for 2016-2018 President Victor Pradhan Vice-president Bal Ram Adhikari General Secretary Bhim Narayan Regmi Secretary Prem Prasad Poudel Treasurer Karuna Nepal Member Shekhar Kharel Member Richa Sharma Member Bimal Khanal Member Sakun Kumar Joshi Immediate Past President Basanta Thapa Editors Basanta Thapa Bal Ram Adhikari Nepalese Translation is a journal published by Society of Translators Nepal (STN). STN publishes peer reviewed articles related to the scientific study on translation, especially from Nepal. The views expressed therein are not necessarily shared by the committee on publications. Published by: Society of Translators Nepal Kamalpokhari, Kathmandu Nepal Copies: 300 © Society of Translators Nepal ISSN: 2594-3200 Price: NC 250/- (Nepal) US$ 5/- EDITORIAL strategies the practitioners have followed to Translation is an everyday phenomenon in the overcome them. The authors are on the way to multilingual land of Nepal, where as many as 123 theorizing the practice. Nepali translation is languages are found to be in use. It is through desperately waiting for such articles so that translation, in its multifarious guises, that people diverse translation experiences can be adequately speaking different languages and their literatures theorized. The survey-based articles present a are connected. Historically, translation in general bird's eye view of translation tradition in the is as old as the Nepali language itself and older languages such as Nepali and Tamang. than its literature. -

Nepali Times Should Be Congratulated London: Stately on the Outside the Point Is, the Money That Came in Derived from Synthetic Sources

#653 26 April - 2 May 2013 20 pages Rs 50 ven while the Election Commission and the Interim FEDERAL EXPRESSION EElectoral Council haggle over who should announce elections and dates, the political leadership is already in EDITORIAL, page 2 campaign mode. There are signs the elections (when, and POLLS if, they are held) are going to be a referendum on identity- MR DAHAL based federalism. Some leaders are campaigning in the districts, while GOES TO DELHI Maoist Chairman Pushpa Kamal Dahal campaigns in by KANAK MANI DIXIT APART the neighbourhood. He was in China last week and page 15 goes to India next week. Could it be that Dahal is trying to ingratiate himself to the two big neighbours as an insurance against possible prosecution for wartime excesses? DIWAKAR CHETTRI 2 EDITORIAL 26 APRIL - 2 MAY 2013 #653 FEDERAL EXPRESSION s a country, Nepal seems 11 months to bridge the gap between condemned to repeat the the positions of those for and against Amistakes of the past. We single-identity federalism. From need to take to the streets to restore the statements of politicians and democracy every couple of decades ethnic pressure groups it is clear that or so because democrats emulate the the elections will essentially be a demagogues they replace as soon as referendum on federalism. they get to power. Revolutionaries Year after year since the last take the country through a ruinous BIKRAM RAI elections, surveys have shown that conflict saying the suffering is a necessary part of Indications are that elections most Nepalis, including those from various ethnic groups, attaining utopia, but when they get to rule they behave have misgivings about identity-based federalism. -

Himalayan Voices VOICES from ASIA 1

Himalayan Voices VOICES FROM ASIA 1. Of Women, Outcastes, Peasants, and Rebels: A Selection of Bengali Short Stories. Translated and edited by Kalpana Bardhan. 2. Himalayan Voices: An Introduction to Modern Nepali Literature. Translated and edited by Michael James Hutt. Himalayan Voices An Introduction to Modern Nepali Literature TRANSLATED AND EDITED BY Michael James Hutt UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS Berkeley Los Angeles Oxford This book is a print-on-demand volume. It is manufac- tured using toner in place of ink. Type and images may be less sharp than the same material seen in traditionally printed University of California Press editions. University of California Press Berkeley and Los Angeles, California University of California Press, Ltd. Oxford, England © 1991 by The Regents of the University of California Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Himalayan voices : an introduction to modern Nepali literature / translated and edited by Michael James Mutt, p. cm. — (Voices from Asia ; 2) Translated from Nepali. Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index. ISBN 0-520-07046-1 (cloth). — ISBN 0-5204)7048-8 (paper) 1. Nepali poetry—20th century—Translations into Knglish. 2. English poetry—Translations from Nepali. 3. Short stories, Nepali—Translations into English. 4. Short stories, English— Translations from Nepali. 5. Authors, Nepali—20th century— Biography. 1. Mutt, Michael. II. Series. PK2598./95E5 1990 891'.49—dc:20 90-11145 CIP Printed in the United States of America The paper used in this publication meets the -

A Light in the Heart: Faces of Nepal Celebrating 75 Years of the United Nations FOREWORD

eart: d Nations the H rs of the Unite yea ating 75 Faces of Nepal ebr l Ce A Light in A Light in the Heart: Faces of Nepal Celebrating 75 years of the United Nations Copyright ©2020 United Nations Development Programme Nepal All rights reserved. This book or any portion thereof may not be reproduced or used in any manner whatsoever without the express written permission of the publisher except for the use of brief quotations in a book review. Printed in Nepal First Printing, October 2020 A Light in the Heart: Faces of Nepal Celebrating 75 years of the United Nations FOREWORD 2020 has been a year of exceptional disruption for the world, This is for the above reason, -to uphold intergenerational compounded by an unprecedented global health crisis and its solidarity- that the book also presents several poems by accompanying economic and social impacts. Besides, in 2020, some Nepal’s greatest and most famous literary figures, such UNDP joined the United Nations team in Nepal to observe as Laxmi Prasad Devkota (Mahakavi) and Madhav Prasad three important events – the seventy-fifth anniversary of the Ghimire, with heartfelt tributes to them. To complement, there United Nations, the thirtieth anniversary of the International are beautiful poems by young poets, who are already part way Day for Older Persons, and the Decade of Healthy Ageing. through their respective literary journeys. In this way, the book embraces expressions from three Nepali generations. Thus, as an acknowledgement of a generation, UNDP organized a virtual exhibition of photographs of seventy-five And so I express sincere gratitude to those featured on the people born with the United Nations, who are featured in this photography – and through them to their whole generation –, book. -

3-50 Page.Indd

MAY 2011 / Rs. 100 www.ecs.com.np ISSN 1729-2751 Art sincethetimeofArniko / Mud, sweat and madness on the mountain / There’s something about Kiwi /Mud,sweatandmadnessonthemountainThere’ssomethingaboutKiwi Art since the time of ww.ecs.com.np MAY 2011 www.ecs.com.np ARNIKO ARNIKOThe history of Nepali art is one that has seen times, both good and bad. However, its essence has remained preserved by dedicated masters. SUBSCRIBER COPY 117 AN EVENING WITH MUSIC MUSEUM OF NEPAL TRIALS AND TRAVAILS 64 KIRAN MANANDHAR 74 A group of music enthusiasts have 10 4 ON THE TRAIL The prolific artist goes candid ensured that Nepali history is documented Reaching Everest Base Camp without a guide about artists and art in Nepal. through musical instruments. and porter provides an altogether different high. Subscribe to Healthy Life For 1 Year (12( Issues) @ Rs. 600 & Pleasure Your Senses with Rs. 1000 worth of Spa Treatment at Chaitanya Spa, Bakhundole, Sanepa To subscribe sms HL at 9851047233 Choose any one of the following six packages Refl exology (Foot massage) & Head & Shoulder Massage Manicure & Steam Spa (Steam, Sauna, Jacuzzi Area Vertebral Message with Doctor Dry Massage-Shiatsu (60min) Sauna (60 min) with Sauna (60 min) Manicure is a spa beauty treatment Usage) (60 min) Consultati on (60 min) Shiatsu is a traditi onal Japanese Refl exology is a method of applying Head and shoulder massage for the fi ngernails and hands which These are forms of hydro- Applying deep pressure of the healing method which works on pressure to the feet and hand with includes massage of head and improves and increases the blood therapy. -

Modernism and Modern Nepali Poetry – Dr

Dancing Soul of Mount Everest Creator & Creation (Selected Modern Nepali Poems) Editing Advisors Dr. Govinda Raj Bhattarai Rajeshwor Karki Proposer Dr. Laxman Prasad Gautam Editor Momila Translator & Language Editor Mahesh Paudyal Publisher Nepali Kalasahitya Dot Com Pratishthan [Nepali Art & Literature Dot Com Foundation] (Under the project of Nepal Academy) Dancing Soul of Mount Everest Creator & Creation (Selected Modern Nepali Poems) Editor : Momila Translator & Language Editor : Mahesh Paudyal Publisher : Nepali Kalasahitya Dot Com Pratishthan (Nepali Art & Literature Dot Com Foundation) ©:Publisher Edition : First, 2011 Copies : 1001 Cover Design : Graphic Workshop Layout : Jeevan Nepal Printer : Modern Printing Press Kantipath, Kathmandu, Phone: 4253195 Price : NRs. 1,200.00 IRs. 1,000.00 US$ 25.00 Euro 20.00 ISBN: 978-9937-2-3657-7 DANCING SOUL OF MOUNT EVEREST (an anthology of selected modern Nepali poems) Editorial Context Heart-Transfer/Moksha Esteemed Readers! Here in editorial context, I extend words of gratitude that express themselves, though they might have remained apparently unexpressed. All of your accepted / unaccepted self-reflections shall become collages on the canvas of the history assimilated in this anthology. Dear Feelers! Wherever and whenever questions evolve, the existential consciousness of man keeps exploring the horizon of possibilities for the right answer even without the ultimate support to fall back upon. Existential revelations clearly dwell on the borderline, though it might be in a clash. In the present contexts, at places, questions of Nepali identity, modernity, representativeness, poetic quality, mainstream or periphery, temporal boundaries and limitations of number evolve – wanted or unwanted. Amidst the multitude of these questions, Dancing Soul of Mount Everest has assumed this accomplished form in its attempt to pervade the entirety as far as possible. -

List of Nepal Collection Available in the Library

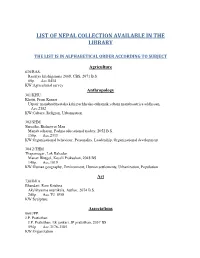

LIST OF NEPAL COLLECTION AVAILABLE IN THE LIBRARY THE LIST IS IN ALPHABETICAL ORDER ACCORDING TO SUBJECT Agriculture 630/RAS. Rastriya krishiganana 2068, CBS, 2071 B.S. 60p. Acc.8434 KW:Agricultural survey Anthropology 301/KHU. Khatri, Prem Kumar Utpati: manabsabhyataka kehi pachhyako etihansik yebam manabsastriya addhyaan, Acc.2182 KW:Culture, Religion, Urbanization 302/SHM. Shrestha, Bisheswar Man Manab acharan, Padma educational traders, 2052 B.S. 156p. Acc.2333 KW:Organizational behaviour, Personality, Leadership, Organizational development 304.2/THM. Thapamagar, Lok Bahadur Manav Bhugol, Koseli Prakashan, 2048 BS 140p. Acc.1019 KW:Human geography, Environment, Human settlements, Urbanization, Population Art 730/BHA. Bhandari, Ram Krishna Akchhyarma murtikala, Author, 2074 B.S. 240p. Acc.TU 1858 KW:Sculpture Associations 060/JPP. J.P. Pratisthan J.P. Pratisthan: Ek jankari, JP pratisthan, 2057 BS 594p. Acc.3176-3185 KW:Organization Biography 920/RAJ. Rana, Hemanta Shamsher Janaral Nara Shamsher Janga Bahadur ranako jiwani, P.B.Rana, 1978 118p. Acc.4112 KW:Nepalese history, Life history 920/SAH. Sahid Muktinath Adhikari: smriti grantha, Shree muktinath Adhikari smriti pratisthan, 2059 B.S. 343p. Acc.TU 232, TU 233 920.71/ACS. Acharya, Bidhan ed. Smritima: S.L. Sharma, Parbati Devi sharma, 2064 B.S. 268p. Acc.7663 923.25496/DHL. Dhamala, Jiwanath Lauhapurush Ganesh Man Singh: jiwan, sangharsh ra rajniti, Pacific publication Pvt Ltd, 2073 B.S. 320p. Acc.TU 1828-TU 1829 KW:Ganesh Man Singh, Political leader 923.25496/SAG. Sapkota, Adarsanarayan Girija prasad koirala: safaltaka sutra, bishleshanatmak jiwanbritanta, Nepal Swawalamban Bikas Sangh, 2064 B.S. 262p. Acc.TU 840-TU 844 KW:Girija prasad Koirala 925.40/BAB. -

A Phonological Study of Tilung: an Endangered

Nepalese Linguistics Volume 27 November 2012 Chief Editor Dr. Dan Raj Regmi Editors Dr. Balaram Prasain Mr. Ramesh Khatri Office Bearers for 2012-2014 President Krishna Prasad Parajuli Vice-President Bhim Lal Gautam General Secretary Kamal Poudel Secretary (Office) Bhim Narayan Regmi Secretary (General) Kedar Bilash Nagila Treasurer Krishna Prasad Chalise Member Dev Narayan Yadav Member Netra Mani Dumi Rai Member Karnakhar Khatiwada Member Ambika Regmi Member Suren Sapkota Editorial Board Chief Editor Dr. Dan Raj Regmi Editors Dr. Balaram Prasain Ramesh Khatri Nepalese Linguistics is a journal published by Linguistic Society of Nepal. It publishes articles related to the scientific study of languages, especially from Nepal. The views expressed therein are not necessary shared by the committee on publications. Published by: Linguistic Society of Nepal Kirtipur, Kathmandu Nepal Copies: 500 © Linguistic Society of Nepal ISSN -0259-1006 Price: NC 400/- (Nepali) IC 350/-(India) USD 10 Life membership fees include subscription for the journal. SPECIAL THANKS to Nepal Academy Kamaladi, Kathmandu, Nepal Nepal Academy (Nepal Pragya Pratisthan) was founded in June 22, 1957 by the then His Late Majesty King Mahendra as Nepal Sahitya Kala Academy. It was later renamed Nepal Rajkiya Pragya Pratisthan and now it is named as Nepal Pragya Prastisthan. This prestigious national academic institution is committed to enhancing the language, cult ure, philosophy and social sciences in Nepal. The major objectives of Nepal Academy include (a) to focus on the