U.S. Recognition of a Commander's Duty to Punish War Crimes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Report by the Military and Veterans Affairs Committee and the Task Force on the Rule of Law Condemning Presidential Pardons of Accused and Convicted War Criminals

CONTACT POLICY DEPARTMENT ELIZABETH KOCIENDA 212.382.4788 | [email protected] MARY MARGULIS-OHNUMA 212.382.6767 | [email protected] REPORT BY THE MILITARY AND VETERANS AFFAIRS COMMITTEE AND THE TASK FORCE ON THE RULE OF LAW CONDEMNING PRESIDENTIAL PARDONS OF ACCUSED AND CONVICTED WAR CRIMINALS On May 6, 2019 and November 15, 2019, President Trump pardoned three Army officers convicted or accused of war crimes: (i) First Lieutenant (“1LT”) Michael Behanna, who was convicted of executing a prisoner he was ordered to release, (ii) 1LT Clint Lorance, who was convicted of numerous crimes, including the murder of two men his soldiers agreed posed no threat to them, and (iii) Major (“MAJ”) Mathew Golsteyn, who was about to stand trial for the murder of a suspected Taliban bombmaker he was ordered to release — and who MAJ Golsteyn repeatedly confessed to killing. The pardoning of military members convicted or accused of battlefield murders appears to be unprecedented in American history.1 These pardons were deeply opposed by many top military commanders because there was no justifiable basis for them, such as a legitimate claim of innocence.2 As former Marine Corps Commandant Charles Krulak stated before the pardons occurred, “[i]f President Trump follows through on reports that he will . pardon[] individuals accused or convicted of war crimes, he will betray [our] ideals and undermine decades of precedent in American military justice that has contributed to making our country’s fighting forces the envy of the world.”3 And as the head of U.S. Army Special Operations Command recently stated in a memo rejecting MAJ Golsteyn’s request to reinstate his Special Warfare tab, President Trump’s preemptive pardon “does not erase or expunge the record of offense charges and does not indicate [MAJ Golsteyn’s] innocence.”4 Instead, what underlies these pardons are President Trump’s misguided views that the 1 The closest example appears to be 2LT William L. -

Copyright by John Michael Meyer 2020

Copyright by John Michael Meyer 2020 The Dissertation Committee for John Michael Meyer Certifies that this is the approved version of the following Dissertation. One Way to Live: Orde Wingate and the Adoption of ‘Special Forces’ Tactics and Strategies (1903-1944) Committee: Ami Pedahzur, Supervisor Zoltan D. Barany David M. Buss William Roger Louis Thomas G. Palaima Paul B. Woodruff One Way to Live: Orde Wingate and the Adoption of ‘Special Forces’ Tactics and Strategies (1903-1944) by John Michael Meyer Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2020 Dedication To Ami Pedahzur and Wm. Roger Louis who guided me on this endeavor from start to finish and To Lorna Paterson Wingate Smith. Acknowledgements Ami Pedahzur and Wm. Roger Louis have helped me immeasurably throughout my time at the University of Texas, and I wish that everyone could benefit from teachers so rigorous and open minded. I will never forget the compassion and strength that they demonstrated over the course of this project. Zoltan Barany developed my skills as a teacher, and provided a thoughtful reading of my first peer-reviewed article. David M. Buss kept an open mind when I approached him about this interdisciplinary project, and has remained a model of patience while I worked towards its completion. My work with Tom Palaima and Paul Woodruff began with collaboration, and then moved to friendship. Inevitably, I became their student, though they had been teaching me all along. -

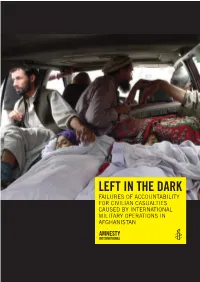

Left in the Dark

LEFT IN THE DARK FAILURES OF ACCOUNTABILITY FOR CIVILIAN CASUALTIES CAUSED BY INTERNATIONAL MILITARY OPERATIONS IN AFGHANISTAN Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 3 million supporters, members and activists in more than 150 countries and territories who campaign to end grave abuses of human rights. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. First published in 2014 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW United Kingdom © Amnesty International 2014 Index: ASA 11/006/2014 Original language: English Printed by Amnesty International, International Secretariat, United Kingdom All rights reserved. This publication is copyright, but may be reproduced by any method without fee for advocacy, campaigning and teaching purposes, but not for resale. The copyright holders request that all such use be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, or for reuse in other publications, or for translation or adaptation, prior written permission must be obtained from the publishers, and a fee may be payable. To request permission, or for any other inquiries, please contact [email protected] Cover photo: Bodies of women who were killed in a September 2012 US airstrike are brought to a hospital in the Alingar district of Laghman province. © ASSOCIATED PRESS/Khalid Khan amnesty.org CONTENTS MAP OF AFGHANISTAN .......................................................................................... 6 1. SUMMARY ......................................................................................................... 7 Methodology .......................................................................................................... -

Turkey Shoot and How Adm

US Navy photo By John T. Correll Battle of the Philippine Sea, Leyte Gulf. It was also overshadowed 1944, the Japanese had scaled back their June 19-20, 1944, marked the by the other war news that month from plans but still hoped to hold a shorter end of Japanese naval airpower halfway around the world: The Allied inner perimeter, anchored on the east by as a signifi cant factor in World War II. landings in Normandy on D-Day, June 6, the Mariana Islands. It was the single biggest aircraft carrier to begin the invasion of occupied Europe. Japan’s greatest hero, Adm. Isoroku battle in history. However, naval history buffs still argue Yamamoto, who had planned the Pearl The fi rst day is remembered as “the about the Turkey Shoot and how Adm. Harbor attack, was dead, his airplane shot Great Marianas Turkey Shoot,” in which Raymond A. Spruance—the non-aviator down over the jungles of New Guinea in US Navy pilots and anti-aircraft gun- in command of the US Fifth Fleet—might 1943 by AAF P-38s. There was no one ners shot down more than 300 Japanese have conducted the battle, but didn’t. of comparable stature to take his place. airplanes. Before the two-day battle was Meanwhile, the US armed forces were over, the Japanese had lost fi ve ships, REVERSAL OF FORTUNES engaged in an intramural argument about including three fl eet carriers, and a total The heyday of the Japanese navy in the strategy. Gen. Douglas MacArthur called of 476 airplanes and 450 aviators. -

Japanese Reflections on World War II and the American Occupation Japanese Reflections on World War II and the American Occupation Asian History

3 ASIAN HISTORY Porter & Porter and the American Occupation II War World on Reflections Japanese Edgar A. Porter and Ran Ying Porter Japanese Reflections on World War II and the American Occupation Japanese Reflections on World War II and the American Occupation Asian History The aim of the series is to offer a forum for writers of monographs and occasionally anthologies on Asian history. The Asian History series focuses on cultural and historical studies of politics and intellectual ideas and crosscuts the disciplines of history, political science, sociology and cultural studies. Series Editor Hans Hägerdal, Linnaeus University, Sweden Editorial Board Members Roger Greatrex, Lund University Angela Schottenhammer, University of Salzburg Deborah Sutton, Lancaster University David Henley, Leiden University Japanese Reflections on World War II and the American Occupation Edgar A. Porter and Ran Ying Porter Amsterdam University Press Cover illustration: 1938 Propaganda poster “Good Friends in Three Countries” celebrating the Anti-Comintern Pact Cover design: Coördesign, Leiden Lay-out: Crius Group, Hulshout Amsterdam University Press English-language titles are distributed in the US and Canada by the University of Chicago Press. isbn 978 94 6298 259 8 e-isbn 978 90 4853 263 6 doi 10.5117/9789462982598 nur 692 © Edgar A. Porter & Ran Ying Porter / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2017 All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. -

Ending the Pacific War: the New History

CHAPTER TWENTY-THREE Ending the Pacific War: The New History RICHARD B. FRANK In 1945, and for approximately two decades thereafter, no significant American controversy attended the use of atomic weapons to end the Pacific War. A national consensus assembled around three basic premises: (a) the use of the weapons was justified; (b) the weapons ended the war; and (c) that in at least a rough utilitarian sense, employment of the weapons was morally justified as saving more lives than they cost (Walker 1990 , 2005 ; Bernstein 1995 ). The historian Michael Sherry branded this as “The Patriotic Orthodoxy” (Sherry 1996 ). Beginning in the mid-1960s challenges appeared to “The Patriotic Orthodoxy.” The pejorative label “revisionists” was sometimes pelted at these challengers, but a more accurate term is just critics. The critics developed a canon of tenets that, in their purest incarnation, likewise formed a trio: (a) Japan’ s strategic situation in the summer of 1945 was catastrophically hopeless; (b) Japan ’ s leaders recognized their hopeless situation and were seeking to surrender; and (c) American leaders, thanks to the breaking of Japanese diplomatic codes, knew Japan hovered on the verge of surrender when they unleashed needless nuclear devastation. The critics mustered a number of reasons for the unwarranted use of atomic weapons, but the most provocative by far marches under the banner “atomic diplomacy”: the real target of the weapons was not Japan, but the Soviet Union (Walker 1990 , 2005 ; Bernstein 1995 ). These two rival narratives clashed along a cultural fault line most spectacularly in the “Enola Gay” controversy in 1995 over the proposed text of a Smithsonian Institution exhibit of the fuselage of the plane that dropped the first atomic bomb. -

Some International Law Problems Related to Prosecutions Before the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia

SOME INTERNATIONAL LAW PROBLEMS RELATED TO PROSECUTIONS BEFORE THE INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL TRIBUNAL FOR THE FORMER YUGOSLAVIA W.J. FENRICK* I. INTRODUCTION The presentation of prosecution cases before the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (the Tribunal) will require argument on a wide range of international law issues. It will not be possible, and it would not be desirable, simply to dust off the Nuremberg and Tokyo Judgments, the United Nations War Crimes Commission series of Law Reports of Trials of War Criminals, and the U.S. government's Trials of War Criminals Before the Nuremberg Military Tribunals Under Control Council Law No.10 and presume that one has a readily available source of answers for all legal problems. An invaluable foundation for legal argument before the Tribunal is provided by Pictet's Commentaries on the 1949 Geneva Conventions, the International Committee of the Red Cross' (ICRC) Commentaries on the Additional Protocols of 1977 to the Geneva Conventions of 1949, the few cases decided since 1950, old case law, and various learned articles and treatises. They must be reviewed and analyzed. At the same time, however, just as the prosecutors in the post-1945 war crimes trials argued successfully that customary law had evolved after 1907 and 1929, so it is reasonable to presume that customary law has evolved since the Geneva Convention of 1949 and the Additional Protocols of 1977. It is essential to pay due heed to the principles of nullum crimen sine lege and nulla poena sine lege.1 One must, however, distinguish * Senior Legal Advisor, Office of the Prosecutor, International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia. -

The Last Eight Days of Japan's Militarists

1 THE LAST EIGHT DAYS OF WWII: HIROSHIMA TO SURRENDER 1 William J. (Bill) Wilcox Jr., Oak Ridge City Historian Retired Technical Director for the Oak Ridge Y-12 & K-25 Plants [During the Manhattan Project (from May 25, 1943) a Jr. Chemist, Tennessee Eastman Corp., Y-12 Plant] A Paper for ORHPA, April 11, 2013. A couple of months ago I ran across an old book 2I had flipped through but not read called “The Fall of Japan” by William Craig. What I read there inspired me to go dig out another nicely detailed account of those last days researched and published by a K-25 chemical colleague, Dr. Gene Rutledge, who in the 1990s, long after retiring, got so interested in this story that he went to Japan and researched the story there making lots of Japanese friends and telling the story of Japan’s two nuclear bomb efforts in more detail than I have seen in any other sources – researched in more detail than have others because of his uranium enrichment expertise at K-25. I also dug out a very contemporary account of those days in TIME magazine’s issue of the week after surrender, an issue that my friend Dunc Lang kindly gave me years ago. I thought you might enjoy hearing a brief summary of those fateful days from these sources. The greatest issue for Japan’s rulers throughout these end-days was the Potsdam Ultimatum or Declaration of July 26, 1945 to which they had officially responded the very next day with words that to them meant “no comment at present” but which most news services overseas mistranslated as a huffy “not worthy of comment.” Although at the “top”, the Japanese government had some semblance to a democracy, it was decidedly not one. -

Military History

Save up to 80% off cover prices on these subjects: Air Combat & Aircraft ···················45 Military Modeling·······················68 American Military History··················8 Naval History ·························59 American Revolution ····················10 Notable Military Units····················57 British Military History ···················67 Spies & Espionage ·····················65 Civil War ·····························12 Uniforms, Markings & Insignia ·············56 Cold War ····························66 Vietnam War ··························15 European Warfare ······················67 WW I & WW II Battles & Campaigns ·········34 Fortresses & Castles ····················59 WW I & WW II Commanders & Units ········39 General Military History ···················2 WW I & WW II Diaries & Memoirs···········30 History of Warfare······················63 WW I & WW II Naval History ··············41 Hitler & the Nazis·······················26 WW I & WW II Spies & Espionage ··········44 Holocaust ····························29 War on Terror ·························67 Korean War···························15 Wartime Journalism ····················64 Military Collectibles ·····················68 Weapons & Military Technology ············58 Military Leaders························69 World War I & World War II ···············18 Current titles are marked with a «. 3891682 SWORD TECHNIQUES OF MUSASHI AND THE OTHER SAMURAI General Military History MASTERS. By Fumon Tanaka. An internationally LIMITED QUANTITY 4724720 SILENT AND renowned -

UAP Attended the Tiger Bay Club of Volusia County's Event in D

2020 UPDATE - ANNUAL REPORT JANUARY 2020 Judge Jeanine Event: UAP attended the Tiger Bay Club of Volusia County’s event in Daytona Beach, FL with Judge Jeanine Pirro and special guest Major Matt Golsteyn and Lieutenant Clint Lorance. Judge Jeanine had the opportunity to see UAP’s NASCAR before it raced in Daytona in February. Stars and Cars: UAP attended the Stars & Cars event in Florida with Pete Hegseth, Clint Lorance, and Don Brown to support our Nation’s fallen & Operation 300. SHOT Show in Las Vegas: UAP met patriots, added supporters to our team, spread the word about our mission & Warriors, and offered attendees a chance to talk with 1LT Clint Lorance at our booth. SOFREP Radio Interview: SOFREP Radio was joined by Fred Galvin, a retired Marine Raider officer of MARSOC FOX Company fame, Phillip Stackhouse, the attorney for Gunnery Sgt. Draher, and Bull Gurfein, CEO of United American Patriots to discuss the MARSOC 3 case. SOF Bad Monkey Podcast Interview: UAP shared links for the SOF Bad Monkey podcast episode that CEO, LtCol David “Bull” Gurfein, appeared on as a guest. David shared information about ongoing cases and UAP’s mission. OAF Nation MARSOC 3 Video: UAP shared a text-based video put together by OAF Nation that explained the details and facts of the incident in Iraq with the MARSOC 3. Major Golsteyn Request Denied: An Army general denied a request by Major Golsteyn to have his Special Forces tab reinstated following his pardon from President Trump. 1 Task & Purpose Article: In the article, Major Golsteyn’s attorney, Phillip Stackhouse, called the Army’s actions a “joke” and he accused the service's leaders of acting against the wishes of the president, who assured Golsteyn his record would be completely expunged. -

Articles Strengthening American War Crimes

ARTICLES STRENGTHENING AMERICAN WAR CRIMES ACCOUNTABILITY GEOFFREY S. CORN AND RACHEL E. VANLANDINGHAM* The United States needs to improve accountability for its service members’ war crimes. President Donald J. Trump dangerously intensified a growing national misunderstanding regarding the critical nexus between compliance with the laws of war and the health and efficacy of the U.S. military. This Article pushes back against such confusion by demonstrating why compliance with the laws of war, and accountability for violations of these laws, together constitute vital duties owed to our women and men in uniform. This Article reveals that part of the fog of war surrounding criminal accountability for American war crimes is due to structural defects in American military law. It analyzes such defects, including the military’s failure to prosecute war crimes as war crimes. It carefully highlights the need for symmetry between the disparate American approaches to its enemies’ war crimes and its own service members’ battlefield offenses. To help close the current war crimes accountability deficit, we propose a comprehensive statutory remedial scheme that includes: the enumeration of specific war crimes for military personnel analogous to those applicable to unlawful enemy * Geoffrey S. Corn is The Gary A. Kuiper Distinguished Professor of National Security at South Texas College of Law Houston. Rachel E. VanLandingham is a Professor of Law at Southwestern Law School in Los Angeles, California. They teach criminal law, criminal procedure, national security law, and the law of armed conflict. They are each former military lawyers and retired Lieutenant Colonels in the U.S. Army and U.S. -

JOINT FORCE QUARTERLY ISSUE NINETY-NINE, 4TH QUARTER 2020 Joint Force Quarterly Founded in 1993 • Vol

Issue 99, 4th Quarter 2020 JOINT FORCE QUARTERLY Social Media Weaponization A Brief History of the ISSUE NINETY-NINE, 4 ISSUE NINETY-NINE, Insurrection Act 2020 Essay Competition Winners TH QUARTER 2020 Joint Force Quarterly Founded in 1993 • Vol. 99, 4th Quarter 2020 https://ndupress.ndu.edu GEN Mark A. Milley, USA, Publisher VADM Frederick J. Roegge, USN, President, NDU Editor in Chief Col William T. Eliason, USAF (Ret.), Ph.D. Executive Editor Jeffrey D. Smotherman, Ph.D. Senior Editor and Director of Art John J. Church, D.M.A. Internet Publications Editor Joanna E. Seich Copyeditor Andrea L. Connell Associate Editors Jack Godwin, Ph.D. Brian R. Shaw, Ph.D. Book Review Editor Brett Swaney Creative Director Marco Marchegiani, U.S. Government Publishing Office Advisory Committee BrigGen Jay M. Bargeron, USMC/Marine Corps War College; RDML Shoshana S. Chatfield, USN/U.S. Naval War College; BG Joy L. Curriera, USA/Dwight D. Eisenhower School for National Security and Resource Strategy; Col Lee G. Gentile, Jr., USAF/ Air Command and Staff College; Col Thomas J. Gordon, USMC/ Marine Corps Command and Staff College; Ambassador John Hoover/College of International Security Affairs; Cassandra C. Lewis, Ph.D./College of Information and Cyberspace; LTG Michael D. Lundy, USA/U.S. Army Command and General Staff College; MG Stephen J. Maranian, USA/U.S. Army War College; VADM Stuart B. Munsch, USN/The Joint Staff; LTG Andrew P. Poppas, USA/The Joint Staff; RDML Cedric E. Pringle, USN/ National War College; Brig Gen Michael T. Rawls, USAF/Air War College; MajGen W.H.